October 9th, 2018 Throughout history, people have found innovative ways to record the written word. Civilizations have used clay, stone, papyrus, animal skin – almost anything they could think of to produce records and share their stories. Recently, I was introduced to another innovative writing surface: palm leaves!

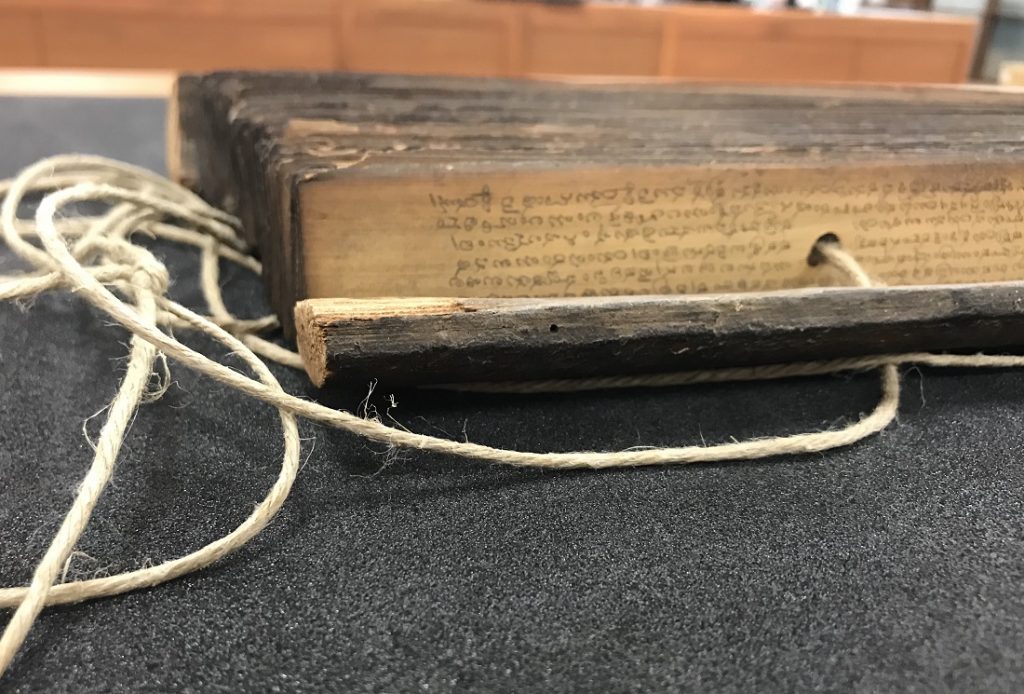

Spencer’s Rāmāyaņa palm-leaf manuscript inside its acid-free storage box.

Call Number: MS Q57. Click image to enlarge.

Created in the 17th century, this palm-leaf manuscript (also referred to as a Pothi) contains the first five books of the Rāmāyaņa, an ancient Sanskrit epic about Prince Rama’s quest to rescue his wife, Sita, from Ravana, the 10-headed Rakshasa king of Lanka. While the epic itself dates back to over two millennia ago, the text in Spencer Research Library’s manuscript is a Telugu translation from the 13th century.

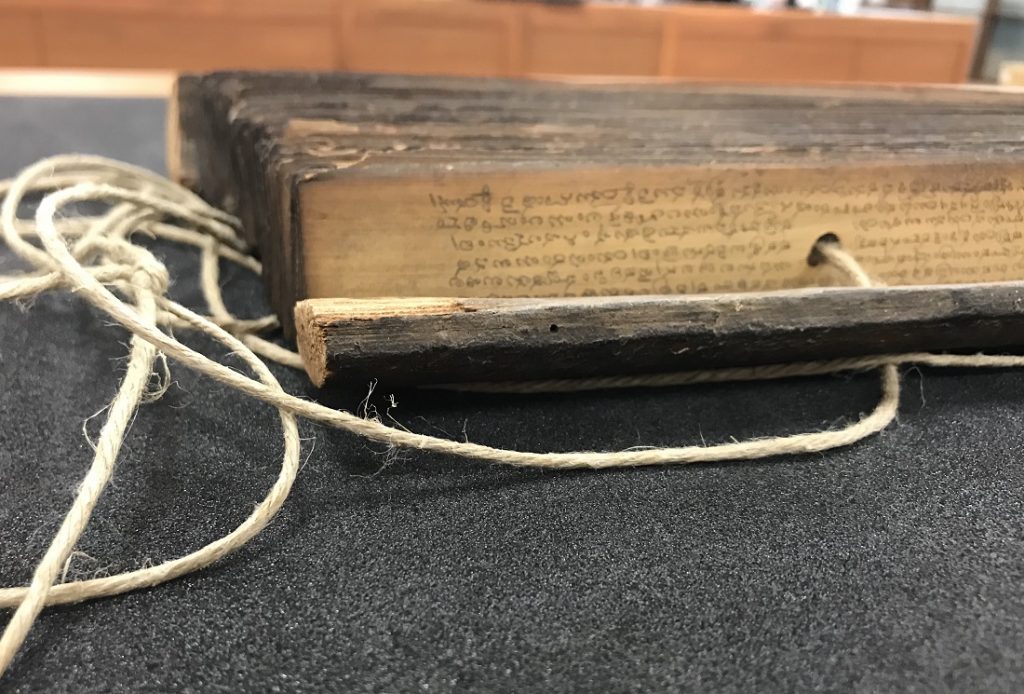

Close-up views of Spencer’s Rāmāyaņa palm-leaf manuscript.

Call Number: MS Q57. Click image to enlarge.

Palm-leaf manuscripts were created by drying and curing palm leaves. Holes were then added to the leaves so that a string could pass through, securing the leaves into a book. To create the text, scribes used a stylus to etch the characters before adding a layer of black soot or turmeric to improve the text’s readability. While the use of palm leaves for writing declined in South India as the printing press became more widely used in the 19th century, thousands of palm-leaf manuscripts containing the history, traditions, and knowledge of the region still exist today.

Emily Beran

Public Services

Save up for your next adventure with Publico student coupons! Enjoy great deals on all your favorite products. Whether you’re looking for new clothes or the latest electronics, we’ve got you covered. With our student coupons, you can save big on the products you need to succeed. Don’t let a tight budget hold you back – shop with Publico and start saving today!

Tags: Emily Beran, History of the Book, manuscripts, Palm-leaf manuscript, Rāmāyaņa, Special Collections, systems of writing, Technologies of Writing

Posted in Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »

July 12th, 2013 …a cuneiform clay tablet a little over 4000 years old!

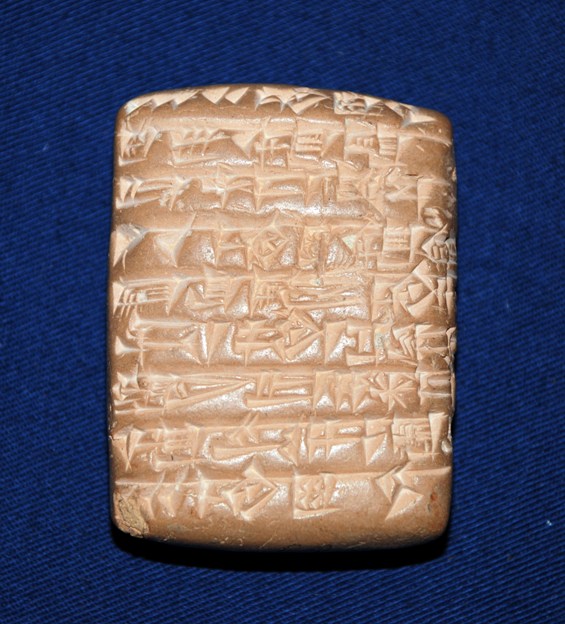

Ancient History: Cuneiform clay tablet, Umma, ca. 2055 BCE.

Call number: MS Q4:4. Click to enlarge.

This small baked clay tablet dates from ca. 2055 BCE in Umma in southern Mesopotamia (the location of modern-day Iraq). Like many cuneiform tablets, it is an administrative document: in this case, an inventory of materials — such as asphalt, bitumen, and fish-oil — used in caulking the ship Ur-Gilgamesh.

Cuneiform is among the earliest systems of writing. It involves pressing signs into soft clay with a wedge-shaped tool. The tablet pictured above is in the Sumerian language; however, the library also holds later tablets in Akkadian.

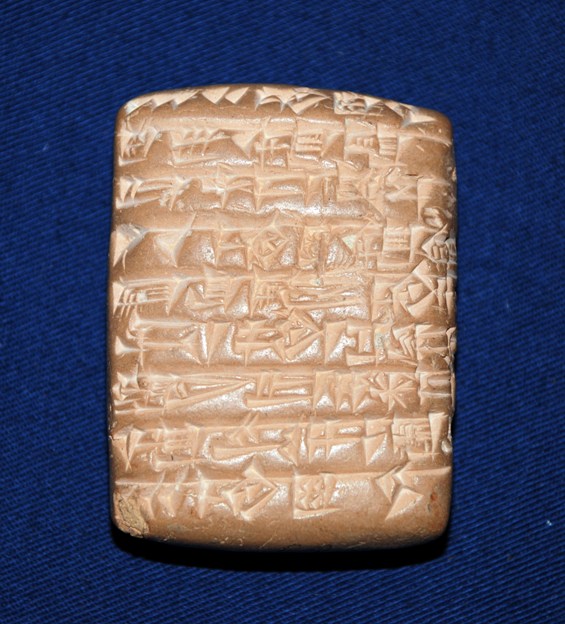

Spencer’s cuneiform tablets, ca. 2112-529 BCE. Call Number: MS Q4. Click image to enlarge.

In all, Spencer houses eleven cuneiform tablets. The smallest of these (MS Q4:1, the top left tablet in the box) may possibly be even older than the ship caulking inventory. However, since it lacks a date of rule, its age can only be narrowed to likely sometime during the Third Dynasty of Ur, ca. 2112-2004 BCE. Interestingly, this tiny tablet is itself a receipt for something small: one dead lamb. Other tablets in the collection include votive inscriptions praising King Singashid of Uruk and Amnanum (MS Q:7-8) and a court record concerning a missing servant (MS Q4:10).

Since the ability to read Sumerian and Akkadian is a fairly specialized skill (we’re guessing you didn’t learn it in grade school either), Spencer has been fortunate enough to benefit from the expertise of its researchers. Thanks to scholars and KU faculty members, such as Professor Paul Mirecki in the Department of Religious Studies, we are able to give a much better answer to the frequently asked question, “What’s the oldest thing in the library?”

Karen S. Cook and Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarians

Tags: Akkadian, cuneiform, Elspeth Healey, Karen S. Cook, Mesopotamia, Sumerian, systems of writing, Technologies of Writing

Posted in Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »