Remembering James E. Gunn and His Alternate Worlds

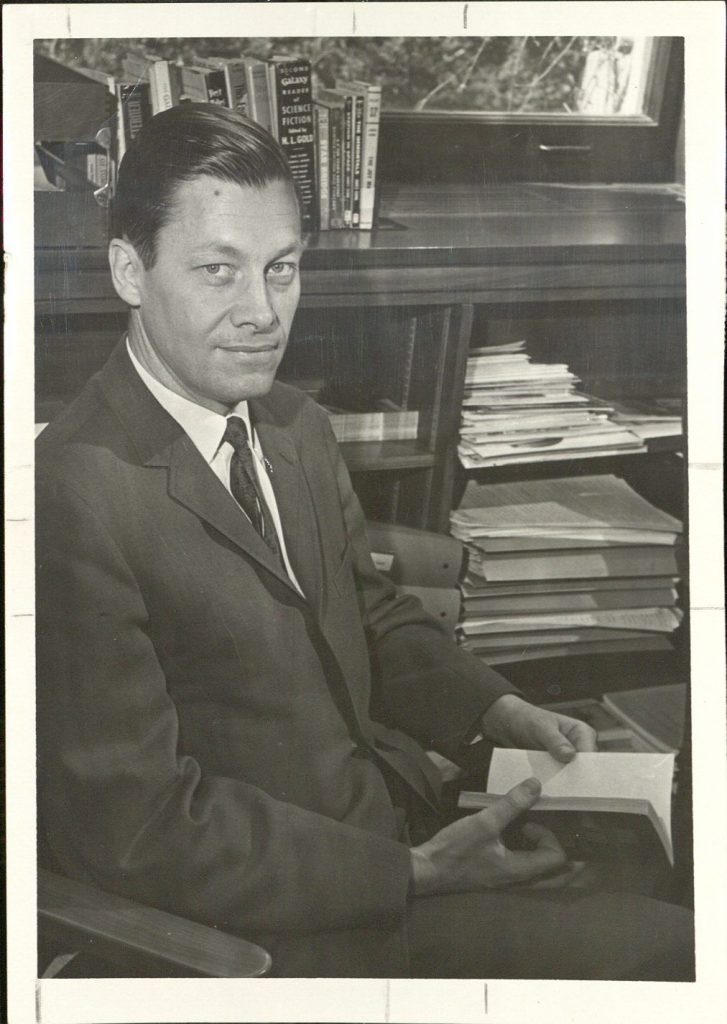

July 7th, 2021July 12 would have been James E. Gunn’s 98th birthday. Though KU’s legend of science fiction died on December 23rd of last year, Gunn (1923-2020) leaves a legacy as one of the genre’s most notable writer-scholars. An author and editor of roughly 50 books (critical studies, works of fiction, and anthologies) with more than 100 short stories to his name, Gunn helped to make Lawrence, Kansas a hub for science fiction. Chris McKitterick, a writer and former student of Gunn’s who succeeded him as Director of KU’s Center for the Study of Science Fiction, affectionately referred to him as “Science Fiction’s Dad” in an illustrated memorial on the Center’s website.

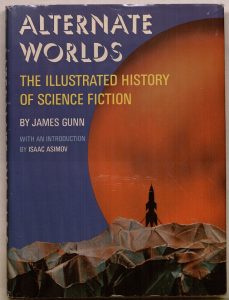

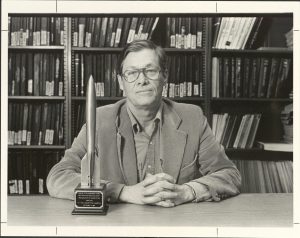

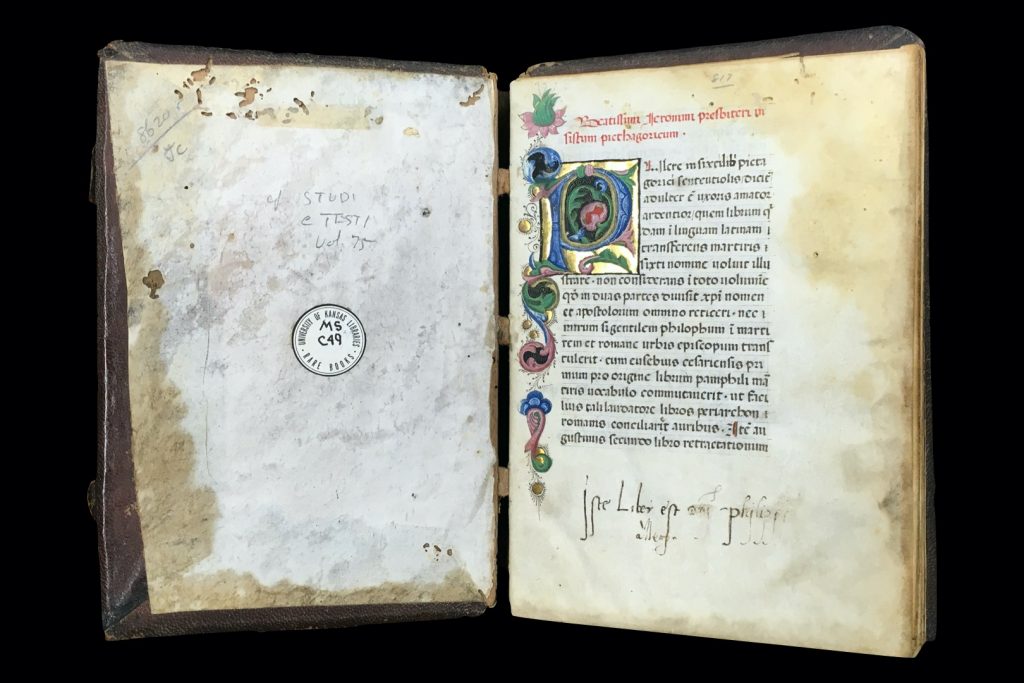

It’s easy to see how Gunn earned that moniker. As one of the first professors to offer courses devoted to science fiction at the college level, he was a teacher and mentor to countless students. The summer institutes and workshops that Gunn established at KU attracted attendees from across the country, and his connections and programming meant that Lawrence received visits from numerous SF luminaries over the years, from Frederik Pohl and Theodore Sturgeon to Nancy Kress to Cory Doctorow. Among Gunn’s scholarly contributions to the field was Alternate Worlds: The Illustrated History of Science Fiction (1975), which drew a number of its images of from Spencer Library’s collections. Of course, at the same time, Gunn was instrumental in building Spencer ’s science fiction holdings. Not only did he donate books and magazines, but he encouraged others to do so as well, helping writers and SF organizations to place their papers and records at the library up until his death. Gunn won a Hugo Award (one of science fiction’s top honors) for another of his works of criticism, Isaac Asimov: The Foundations of Science Fiction (1982). In a 2007 ceremony, he was honored with the “Damon Knight Grand Master Award” by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) and was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2015.

Left: James Gunn’s Alternate Worlds: The Illustrated History of Science Fiction. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, 1975. Call #: E2598. Right: Gunn with his 1983 Hugo Award (in the category of “Best Related Work”) for his study Isaac Asimov: The Foundations of Science Fiction (1982). University Archives. Call #: RG 41: Faculty Photos: Gunn, James. Click images to enlarge.

Given what he achieved, it’s easy to forget his humble beginnings, but materials from his papers on deposit at the Spencer Research Library offer a glimpse of what it was like to be a young science fiction writer in the 1950s.

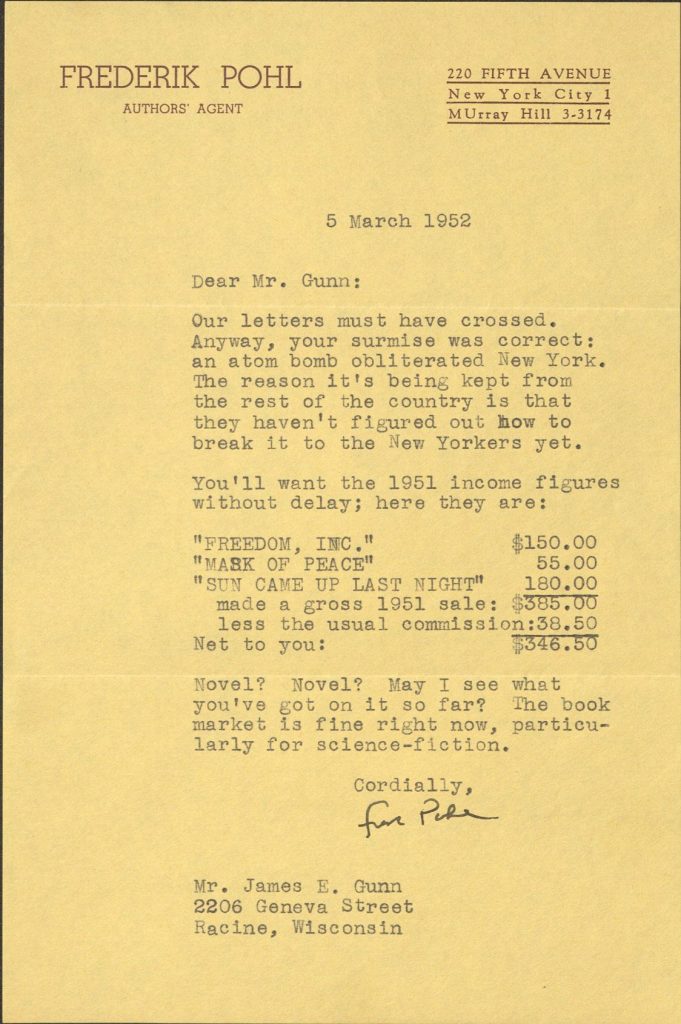

To this day, most speculative fiction magazines pay writers by the word. Current rates include 8-12 cents per word for stories published in Fantasy & Science Fiction, 8-10 cents per word for Asimov’s, and 10 cents per word for the online Uncanny Magazine. An early letter in Gunn’s papers from 1952 reports the income from some of his first science fiction sales. In his memoir Star-Begotten (2017), Gunn recalls that Planet Stories paid a rate of 1¼ cents per word for his 12,000-word “Freedom, Inc.,” but then (to Gunn’s chagrin) changed the title of the novelette to “The Slaves of Venus.”[i] Observant readers will note that the letter comes from another famed SF writer Frederik Pohl, who was still then working as a literary agent, though Pohl would soon abandon agent work to devote himself to writing and editing science fiction.

Being paid for one’s writing has always been important point of pride for the genre of science fiction. Early in his career, Gunn made a decision:

…I would write my novels in the form of short stories and novelettes that I could get published first in magazines and later collect as books. When I became a teacher of fiction writing, I passed this along to my students as “Gunn’s Law” (Sell it twice!).[ii]

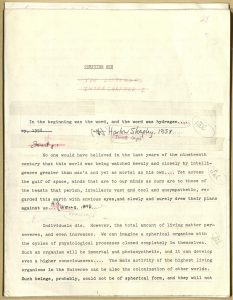

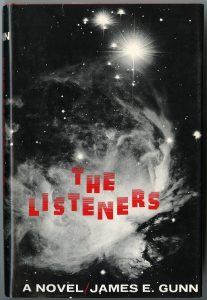

It was a law that Gunn often followed. His novel The Immortals (1962), which presciently imagines a dystopian future where advances in medicine have enabled the richest to live increasingly long lives, while most in society suffer under staggering medical costs, was comprised of four previously published novelettes. When The Immortals was adapted (with significant changes) into a popular TV movie of the week as The Immortal, Gunn also wrote a novelization of the script. Likewise, Gunn’s novel The Listeners (1972) was first published as a series of stories in Galaxy magazine (and one also appearing in The Magazine of Science Fiction and Fantasy) between 1968 and 1972. The novel, which explores interstellar communication and the effects on individuals and society of the attempts at first contact with distant alien cultures, was dedicated “To Walter Sullivan, Carl Sagan, and all of the other scientists whose books and articles and lectures and speculations provided, so clearly, the inspiration and source material for this book […].” It seems Carl Sagan’s imagination was also stirred in return. As Gunn reports in his memoir, Sagan later sent him his own novel of interstellar communication, 1985’s Contact, “inscribed with ‘thanks for the inspiration of The Listeners.’” Gunn’s story received accolades from the broader field as well. The first of the sections published in Galaxy (“The Listeners”) was nominated for the 1969 Nebula Award for Best Novelette, and the subsequent novel was in 1973 the runner-up for the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Novel.

Left: Typescript with instructions for the first of the quotation-laden “Computer Run” interchapters that appear after each chapter of The Listeners, 1972. James Gunn Papers. Call number: MS 116A:1a. Right: Gunn, James E. The Listeners. New York: Scribner’s, 1972. Call #: ASF Gunn C26 Click images to enlarge.

And though with endless energy and good will James Gunn helped his students navigate the practical and business aspects of the field science fiction, it was his belief in the genre’s ideas and their potential to bring about change that arguably stands as the most potent force across Gunn’s fiction and criticism. It was this potential that James Gunn heralded in his remarks at his 2015 induction into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame. “A lot has happened to science fiction since I sat in a garret writing my first story in 1948,” he explained;

[…] The world has changed, too, often in positive ways, sometimes in ways that threaten its survival. It’s the job of science fiction, it’s our job, to observe those changes and consider their implications for human lives and maybe even do something to make those lives better, more livable, more human—whatever “human” turns out to be. Let’s save the world through science fiction.[iii]

Over the years, many of Gunn’s students and readers have taken up that call and will continue to be inspired by it, even in his absence.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian

[i] Gunn, James E. Star-Begotten: A Life Lived in Science Fiction. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2017: 68.

[ii] Gunn, James E. Paratexts: Introductions to Science Fiction and Fantasy. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2013: 10.

[iii] Gunn, James E. Star-Begotten: A Life Lived in Science Fiction. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2017: 189.

![Marcas de fuego from the Convento de san Agustín (Puebla, Puebla) on Spencer Research Library's copy of Biblia polyglotta. Alcala de Henares: in Complutensi universitate, industria Arnaldi Gulielmi de Brocario, 1514-1517 [i.e. 1520 or 1521]. Call # Summerfield G41.](https://exhibits.lib.ku.edu/files/original/46c9f79ac0226357bb080b0e11e0f47d.jpg)

![Image showing the colophon in MS D2 on folio 184v, in which the scribe mentions their name (“Iacobus Tirabuschus B[er]gomensis”) and the date of the completion of the copying of the manuscript (“MoccccoLxxo die decimo nono Octobris”) in Martial, Epigrams, Italy (?), October 19, 1470. Call # MS D2.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/KSRL_MS_D2_folio_184v_detail-1024x683.jpeg)