Manuscript of the Month: Manuscript Waste Not, or a Case in Fragmentology

August 31st, 2021N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

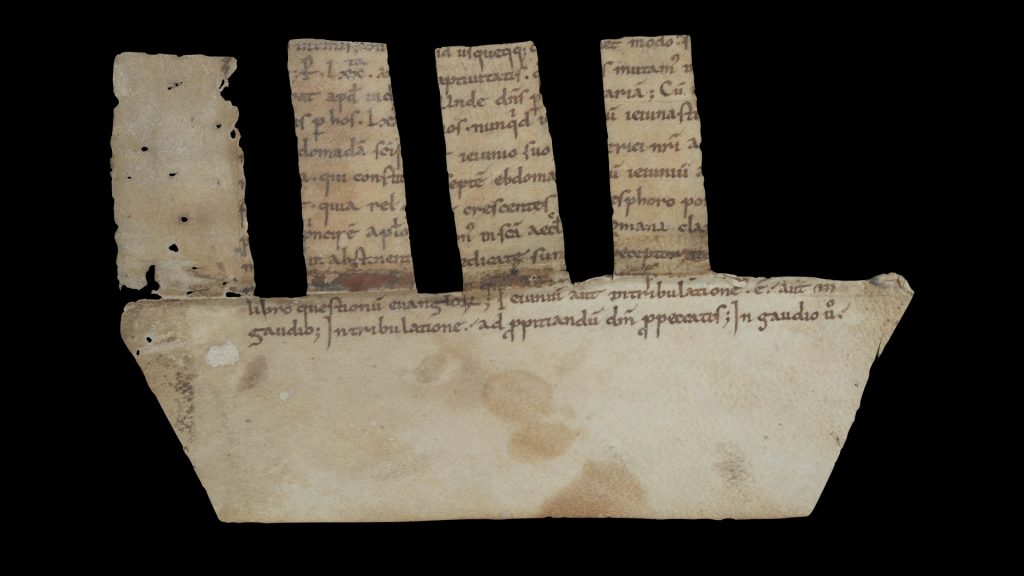

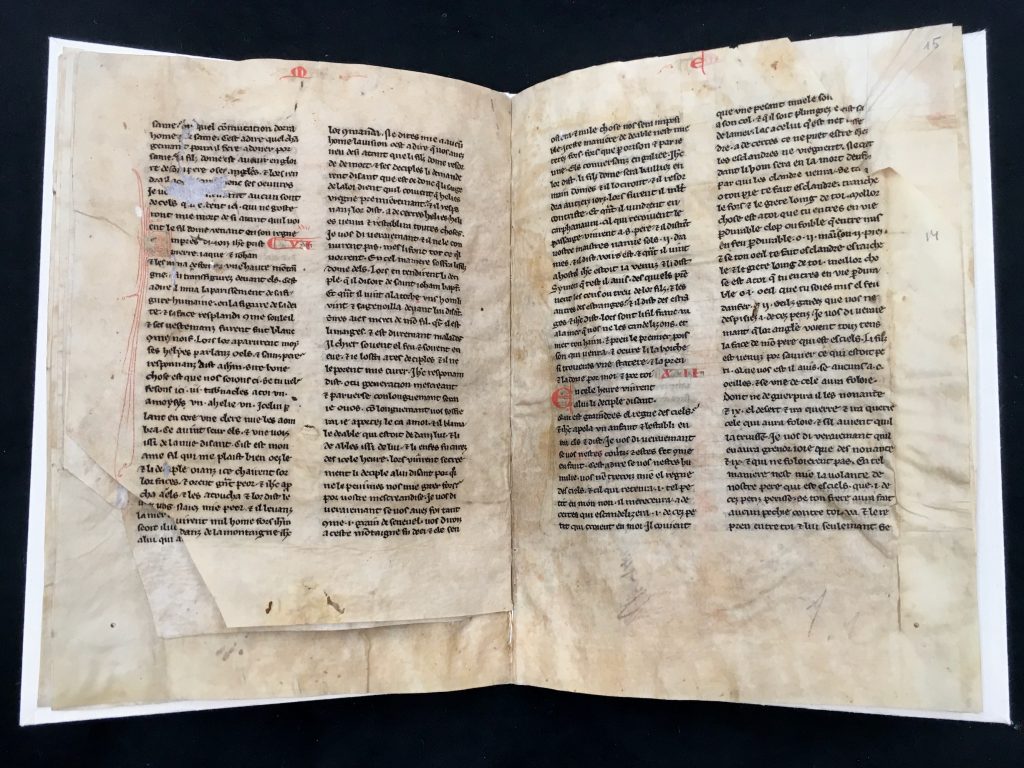

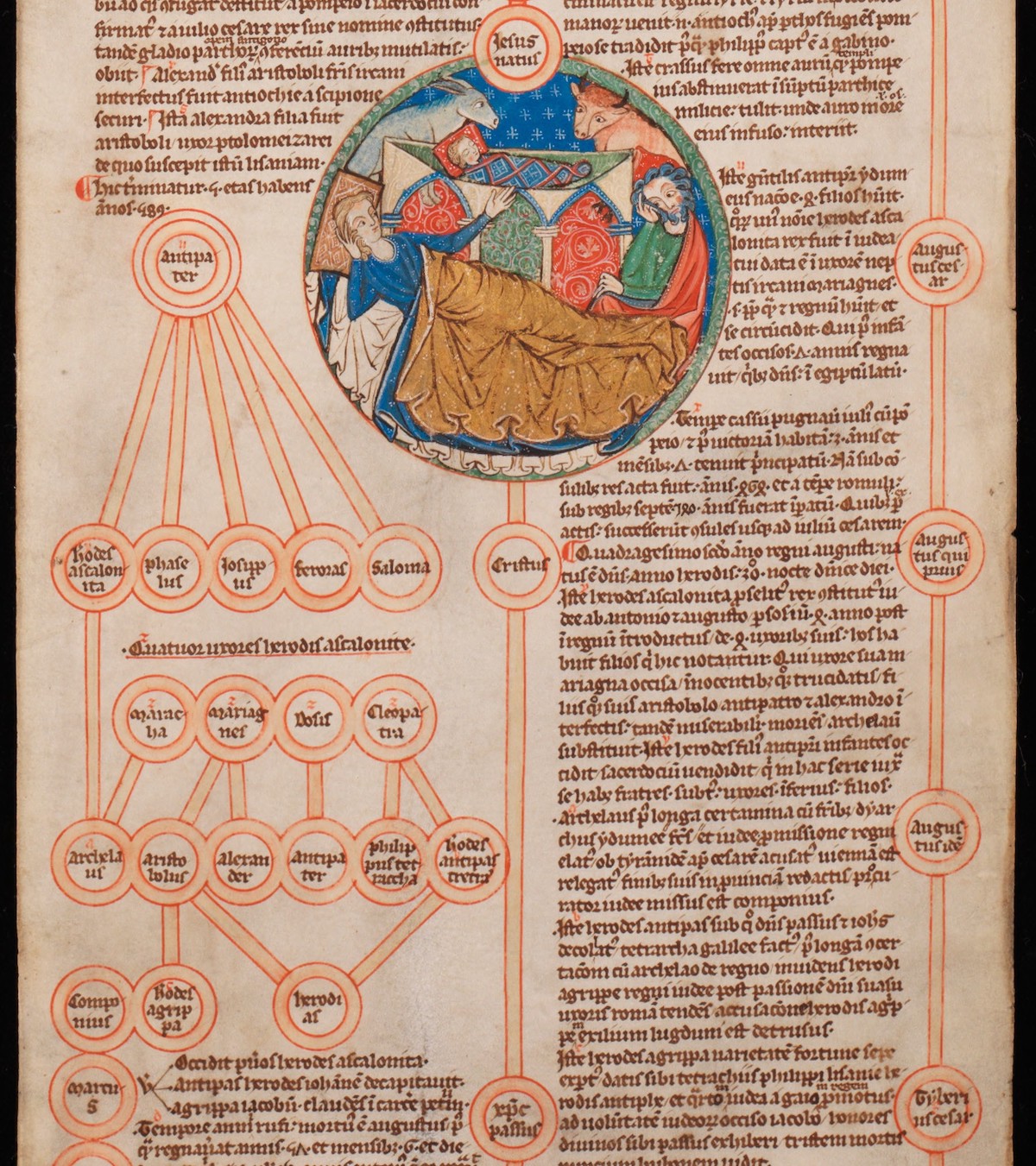

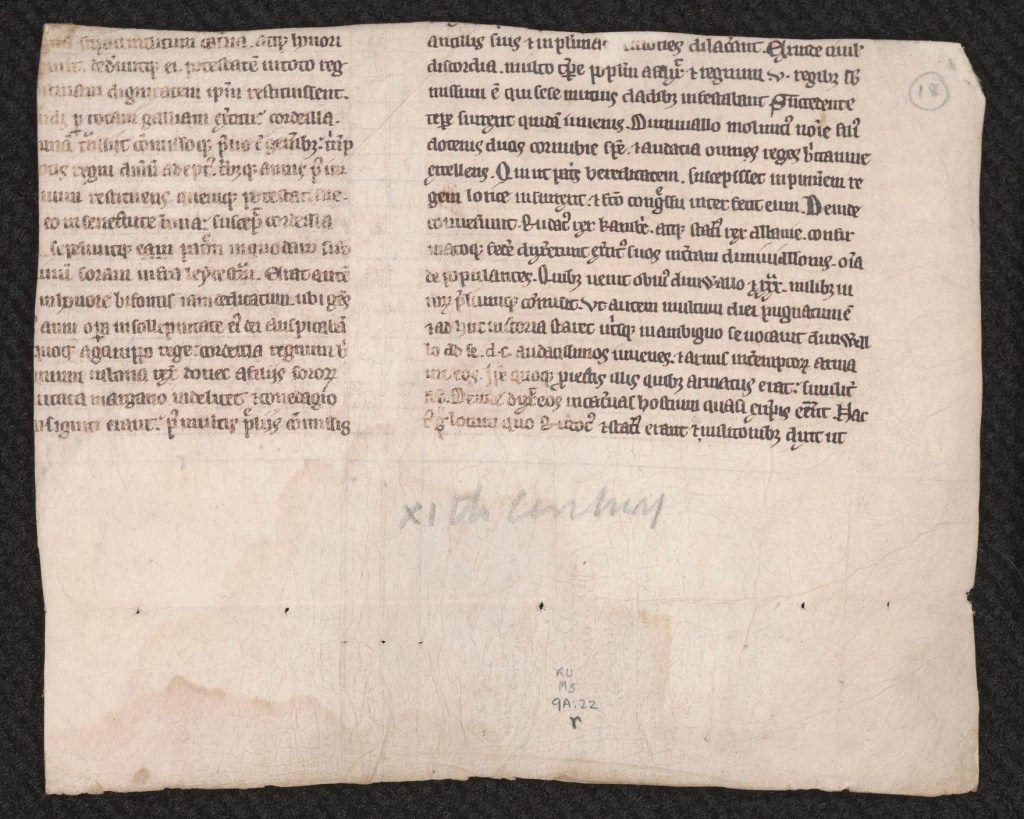

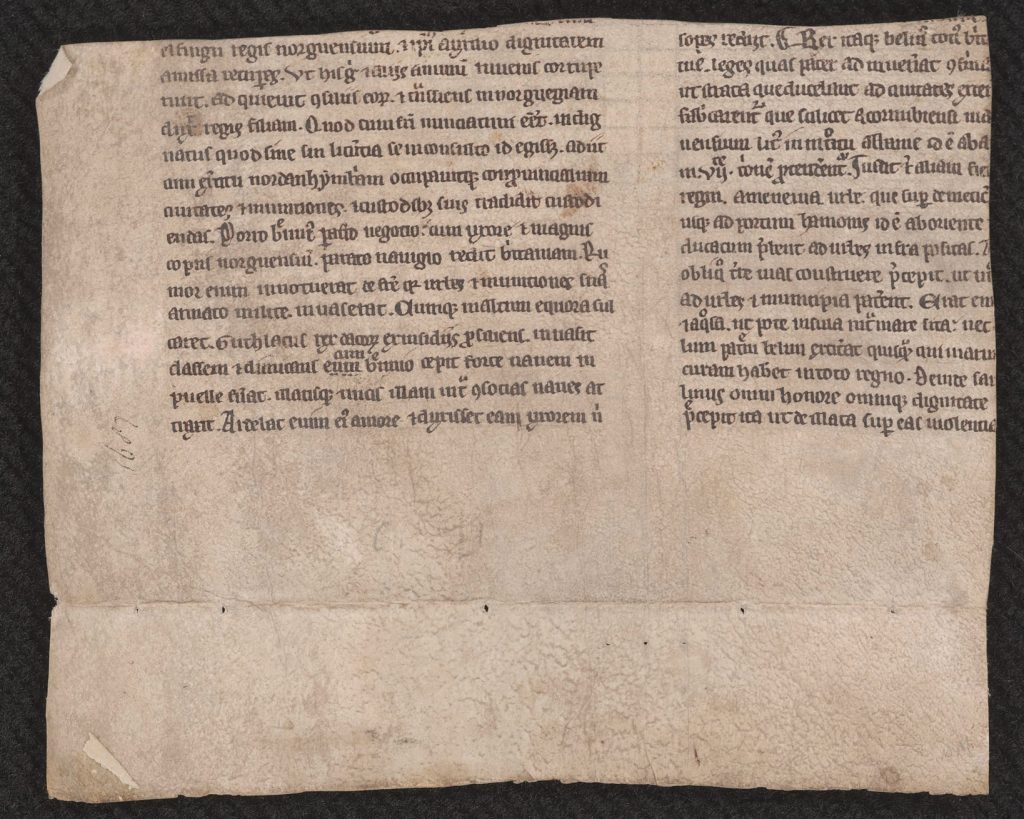

Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS 9/2:31 is one of the fragments in the “Paleographical Teaching Set” that was gradually put together in the second half of the twentieth century for facilitating teaching and learning of Greek and Latin paleography at the University of Kansas. We do not have any information about the origin or the history of the fragment, and the Latin text it contains had not been identified until now (no surprise, perhaps, given the largely illegible and mutilated nature of the parchment). The manuscript has been known at the Spencer Library as the “gaudio fragment.” The reason for this is that the word “gaudio” [joy], which is repeated twice on one side of the fragment, is one of the few easily legible words. Without the identification of the text it contains, this became a practical way to refer to MS 9/2:31.

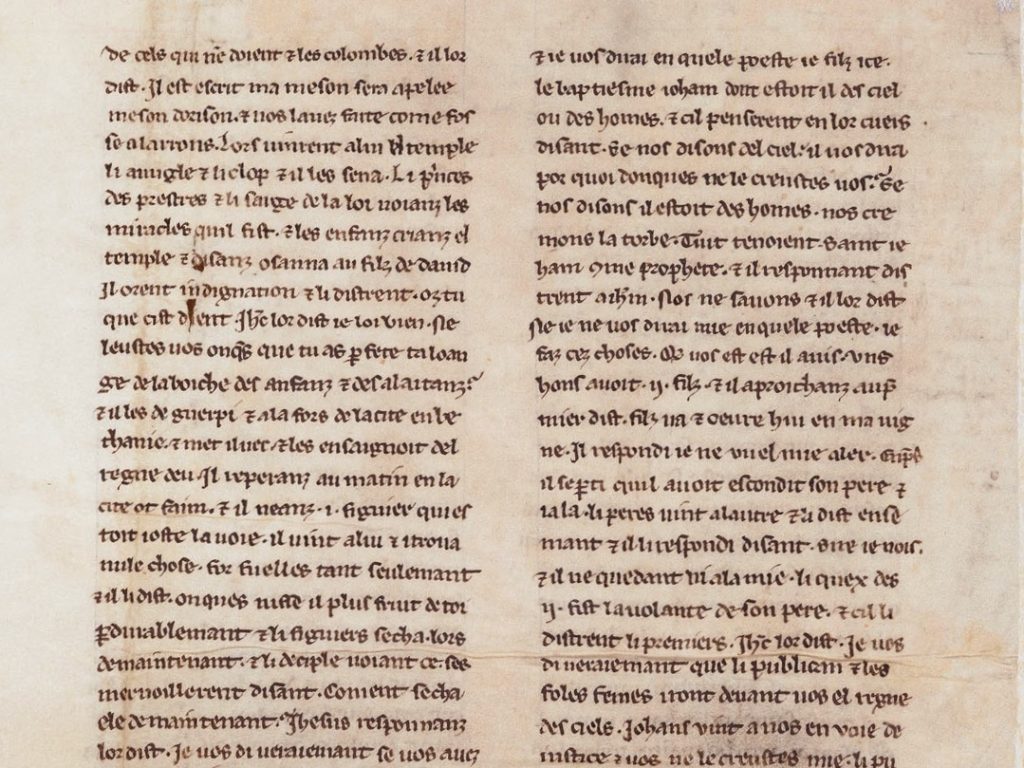

Careful investigation now has revealed that MS 9/2:31 contains part of the first chapter of the first book of the De ecclesiasticis officiis libri quatuor [Four Books on Ecclesiastical Offices] by Amalarius of Metz (approximately 780–850). Amalarius was employed at the courts of both Charlemagne (748–814) and his son and successor Louis the Pious (778–840). He was the bishop of Trier (812–813) and Lyon (835–838), and in 813 was sent as the Frankish ambassador to the Byzantine Empire, to Constantinople (modern day Istanbul, Turkey). Written between the years 820 and 832, the De ecclesiasticis officiis was dedicated to Louis the Pious.

Since the text was previously unidentified, the sides of MS 9/2:31 were also misattributed, with the text beginning on what is thought to be the verso side and continuing some fifteen lines later on the other side. As it stands, MS 9/2:31 is less than half of the original leaf. It measures approximately 100 x 170 mm, with 12 lines of text remaining, of which only 2 lines are fully visible on each side. Although the fragment contains an early witness to the De ecclesiasticis officiis by Amalarius of Metz, its later use as a binding component is more interesting for book history.

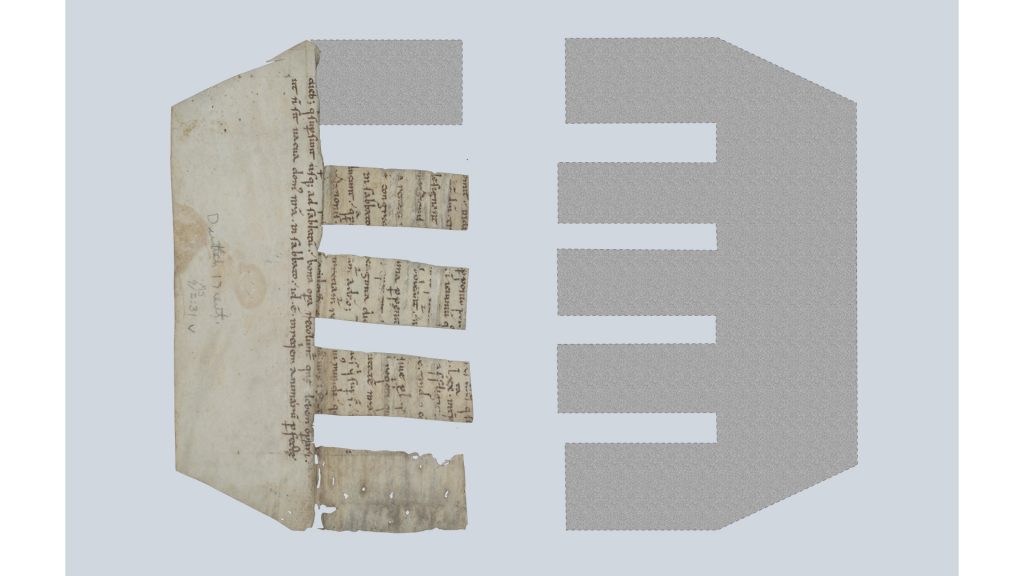

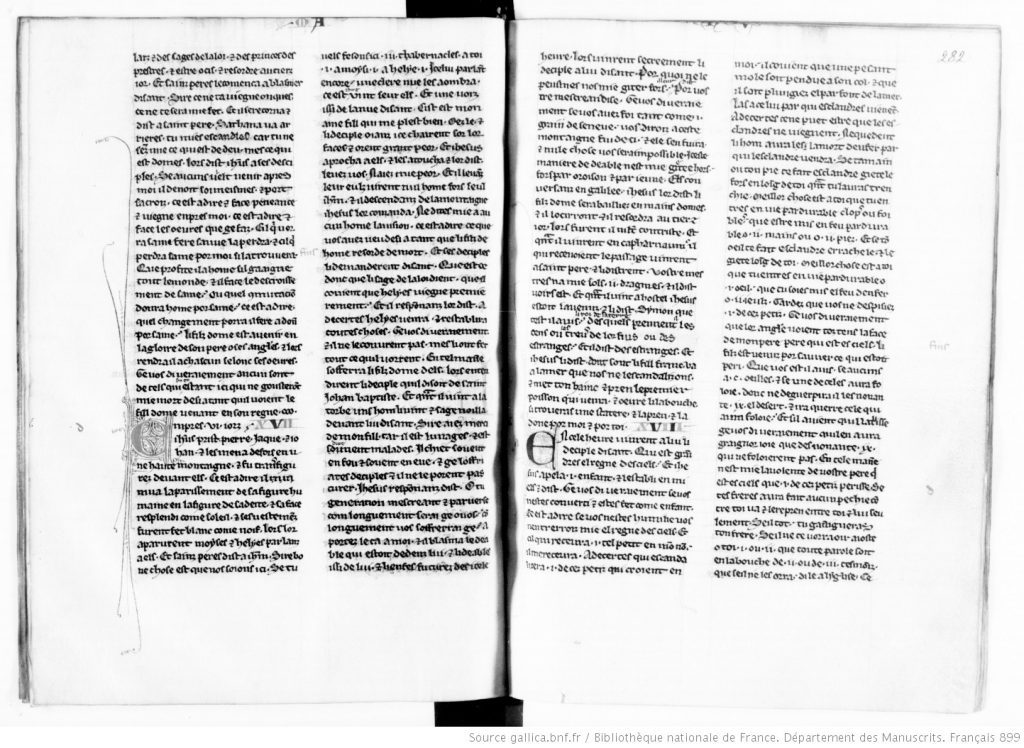

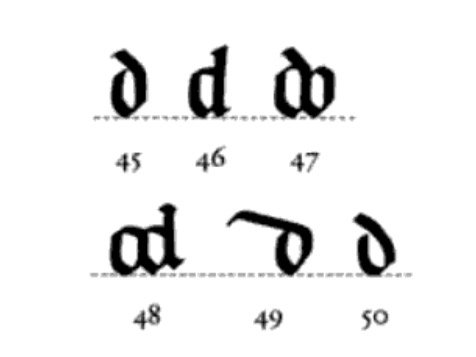

The peculiar shape of MS 9/2:31 is due to the fact that it was repurposed at some point in its later history; the leaf was cut to shape and used as a spine lining of another codex. It was then detached from this codex before it was incorporated into the collections of the Spencer Library. Until recently, it was common for repurposed fragments to be removed from their bindings, either by booksellers or by the holding institutions, and to be inventoried (or sold) separately. There are annotations in pencil in a modern hand in the lower margin of the recto side of MS 9/2:31: “Dutch,” or more likely “Deutsch [German]” and “17th cent.” This inscription probably refers to the codex from which the fragment came, perhaps a manuscript written (or a book printed) in the seventeenth century in Germany (or the Netherlands). This specific type of lining is called comb spine lining, which takes its name from its appearance of a comb with wide teeth due to the slots along one of the edges of the parchment.

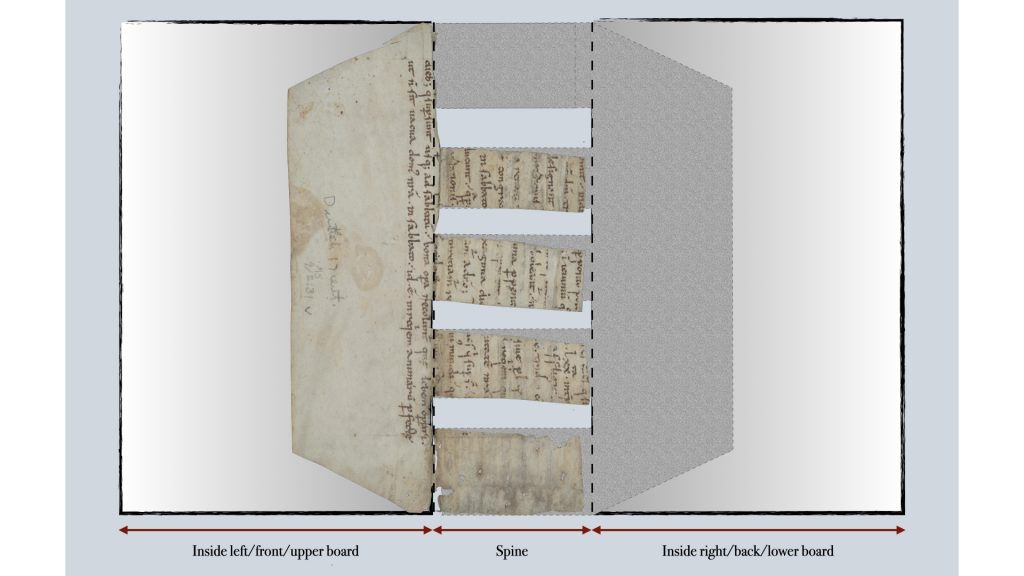

As a comb spine lining, MS 9/2:31 would have been used vertically and it would have had another tooth, which is now missing, as seen in the reconstruction above. Furthermore, it probably had a counterpart as comb spine linings usually consist of two parchment (rarely paper) parts. A similar example of a comb spine lining, also detached from the codex in which it was found, is Cambridge, Trinity College, R.11.2/21. In this case, both parts of the lining survive, and not only that, they are made from the same leaf. So, it is more than likely that the other half of the original leaf of MS 9/2:31 was used as its counterpart in the comb spine lining.

In the codex, the teeth of the two parts of the comb spine lining would have lain over each other in the spine panel. The outer halves of each lining (the parts that are not slotted), which are called lining extensions, probably would have been adhered to the inside of the boards of the codex. From this reconstruction we can tell that the codex for which the spine lining was used was approximately 170 mm in height and had four sewing supports, which would have corresponded to the empty slots created by the teeth of the spine lining. Comb spine linings were used from the later Middle Ages onwards in continental Europe, most notably in Germany, Italy and France. The survival of fragments such as MS 9/2:31 is significant not only because of the texts they contain; they also enable scholars to study and understand medieval and early modern book structures, and in some cases localize and date manuscripts. Although often called “manuscript waste” in scholarship because the original manuscripts were discarded for whatever reason, these repurposed fragments clearly did not go to waste and there is still much we can learn from them.

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

![Image of a manuscript fragment (recto) possibly from Papias the Lombard’s Elementarium doctrinae rudimentum [Elementary Introduction to Learning]. France? Netherlands? 13th century? The fragment had been repurposed as the cover of a codex.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/01.-KSRL_MS-9-2-16_folio1r-1024x683.jpg)

![Image of a manuscript fragment (verso) possibly from Papias the Lombard’s Elementarium doctrinae rudimentum [Elementary Introduction to Learning]. France? Netherlands? 13th century? The fragment had been repurposed as the cover of a codex.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/02.-KSRL_MS-9-2-16_folio1v-1024x683.jpg)

![Image of a manuscript fragment possibly from Papias the Lombard’s Elementarium doctrinae rudimentum [Elementary Introduction to Learning]. France? Netherlands? 13th century?, digitally processed to enhance the legibility of water-damaged text.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/03.-KSRL_MS-9-2-16_folio1r_manipulated-1024x683.jpg)