Manuscript of the Month: The Genealogy of Christ, Medieval Edition

December 29th, 2020N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

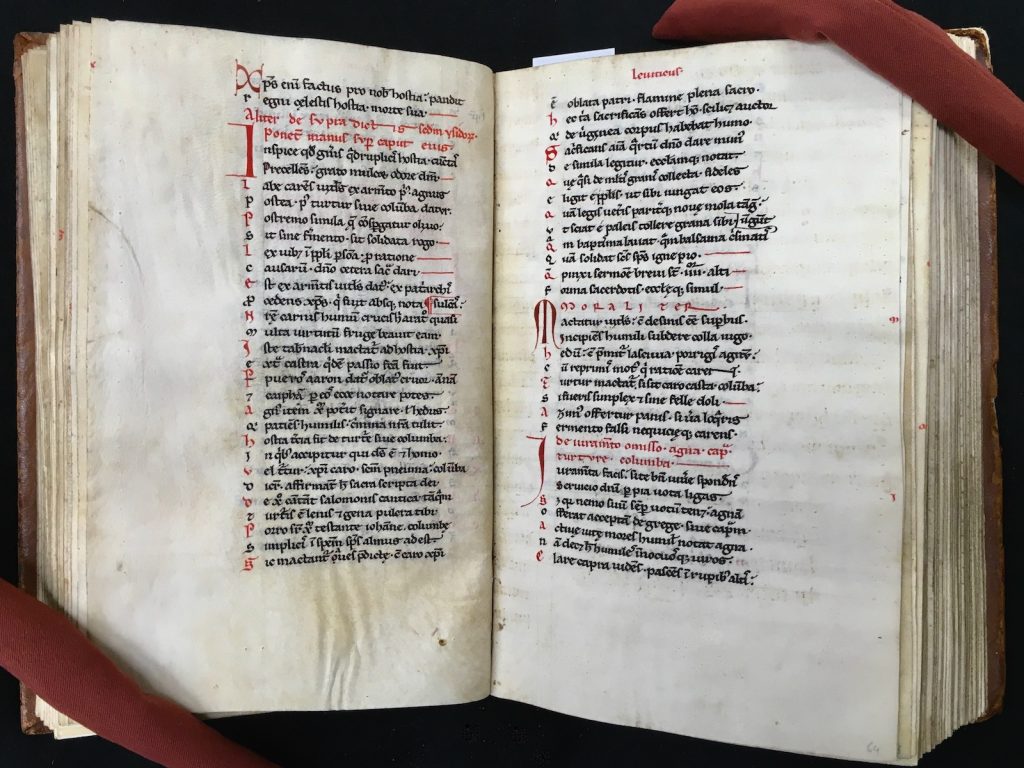

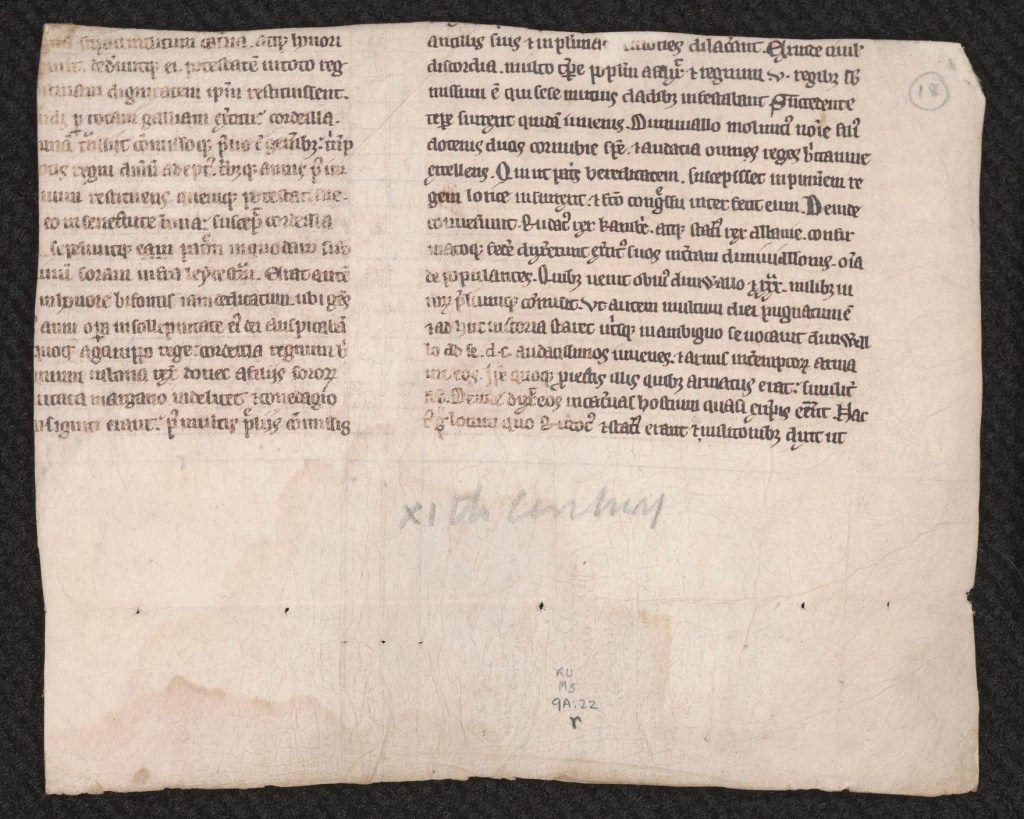

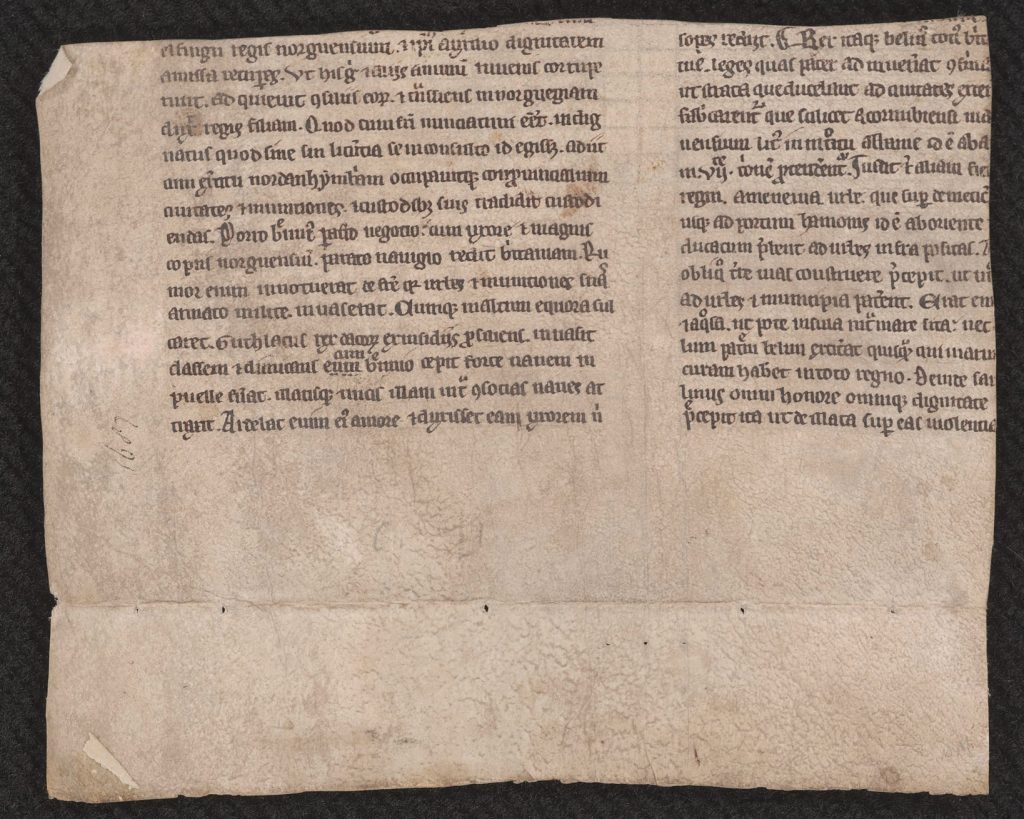

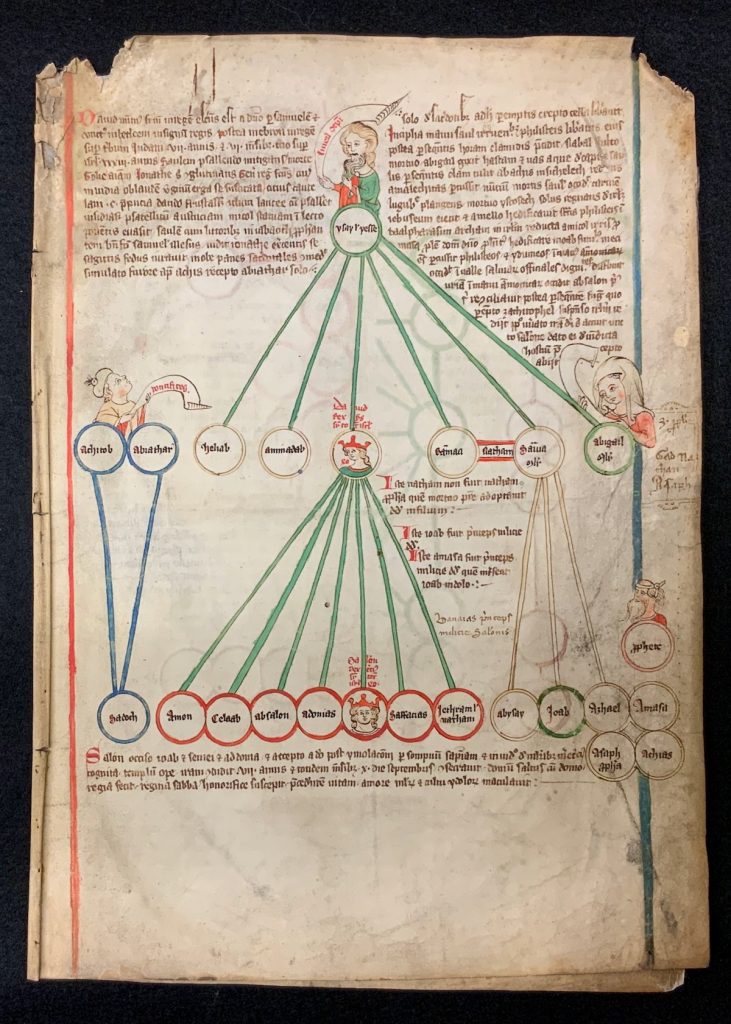

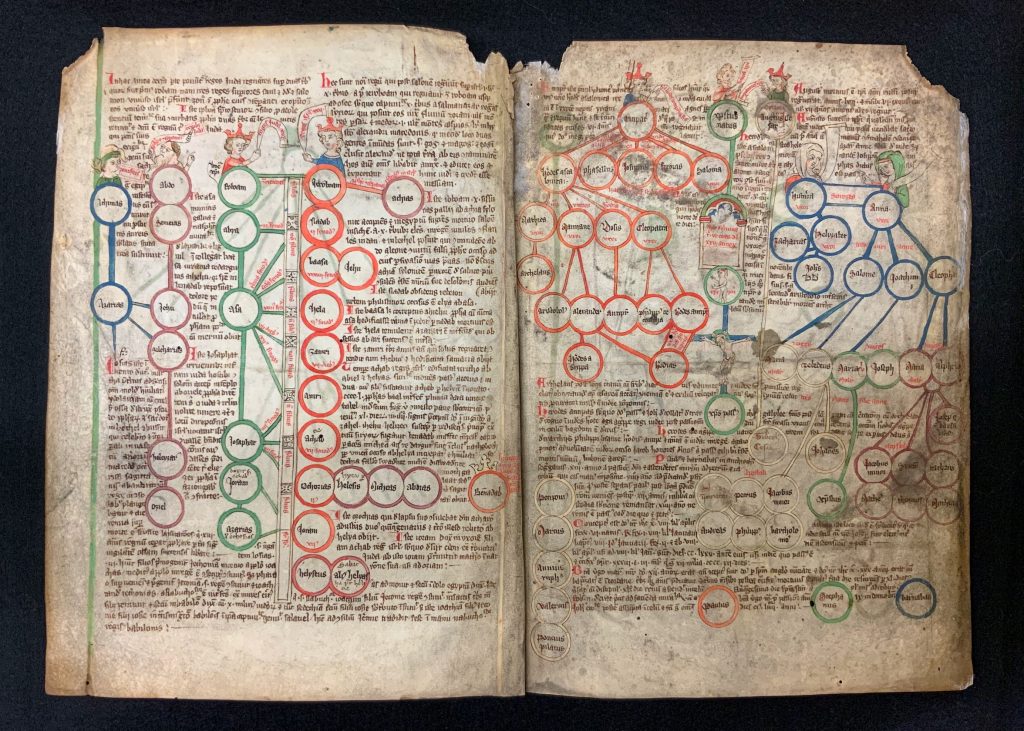

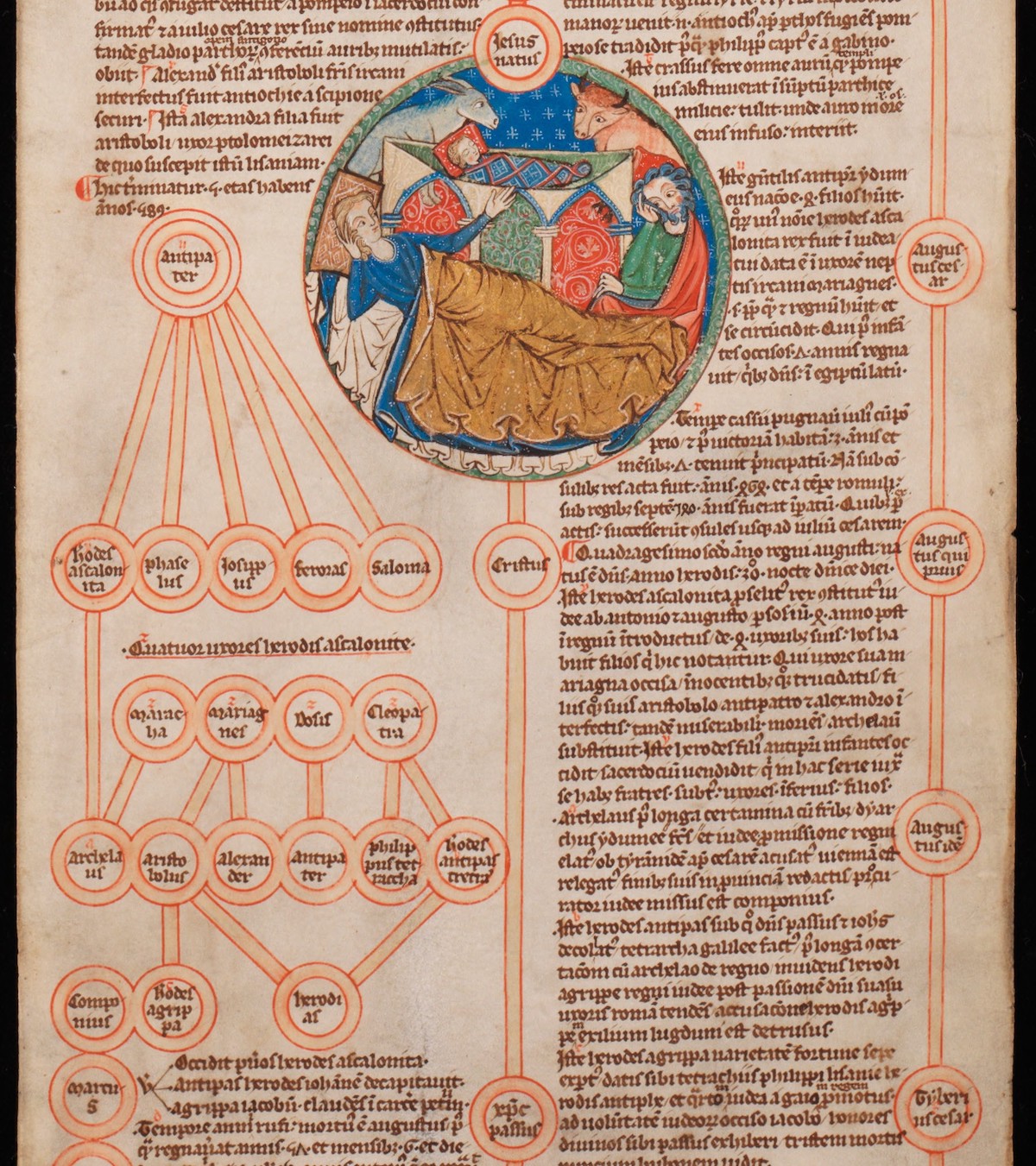

Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS 9/2:29 contains part of the Compendium historiae in genealogia Christi (‘Compendium of the History on the Genealogy of Christ’) compiled by Peter of Poitiers (approximately 1130–1205/1215). Peter’s Compendium is a condensed summary of biblical history arranged in the form of a genealogical tree of Christ that traces his lineage back to Adam. In the text, biblical personages such as Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesse and David are all presented as being directly related to Jesus. Like many of its medieval counterparts, the history is organized according to the concept of the “six ages of the world,” which was first formulated by Augustine of Hippo (354–430). According to this traditional periodization, each of the first five ages lasted approximately a thousand years, with the first extending from Adam to Noah, the second from Noah to Abraham, the third from Abraham to David, the fourth from David to Zedekiah, and the fifth from Zedekiah to Christ. The birth of Christ commences the sixth and final age of the world. Instead of a continuous narrative detailing the events through these ages, however, Peter’s Compendium utilizes a graphic genealogical tree made up of roundels connected by lines and includes brief entries that surround this linear genealogy.

Peter of Poitiers taught theology at the University of Paris, where he succeeded Peter Comestor (approximately 1100–1178/1179) as chair in 1169. He was also Chancellor of the University of Paris from 1193 to his death. It is argued that Peter wrote the Compendium as an educational tool, somewhat continuing in the footsteps of his predecessor Peter Comestor, who also composed a biblical history spanning from the Creation to the Ascension titled the Historia scholastica (‘Scholastic History’). Peter Comestor’s Historia is known to have been included as part of the university curriculum and indeed, in several manuscripts, such as Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 029 dated to the early thirteenth century, Peter of Poitiers’s very short Compendium is found together with Peter Comestor’s much longer Historia.

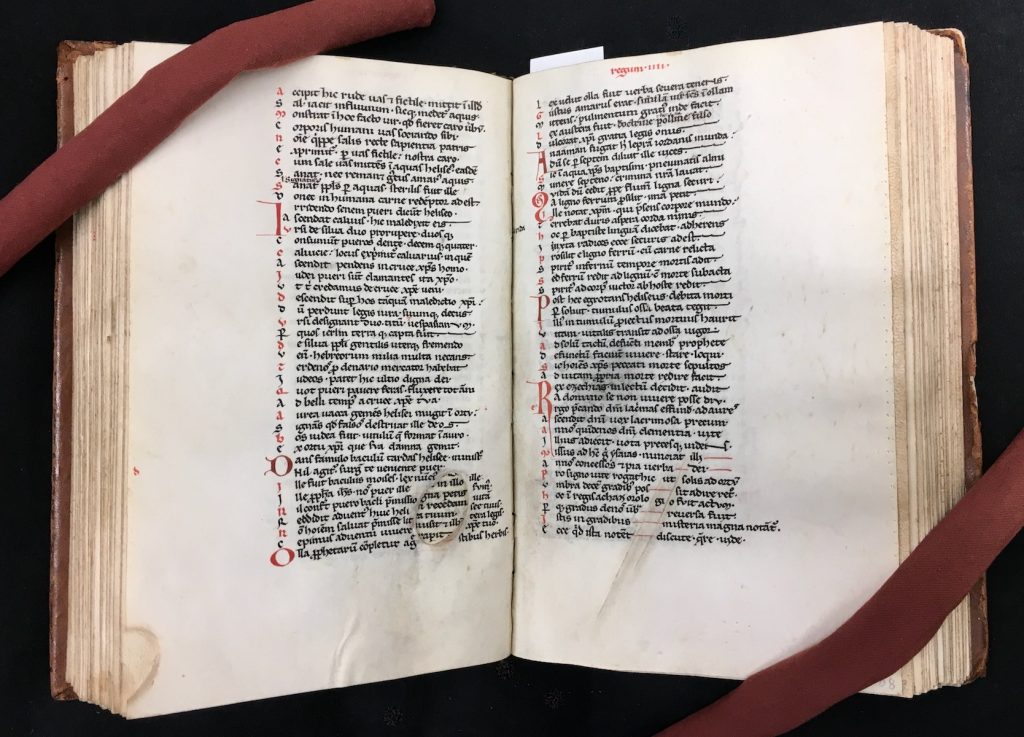

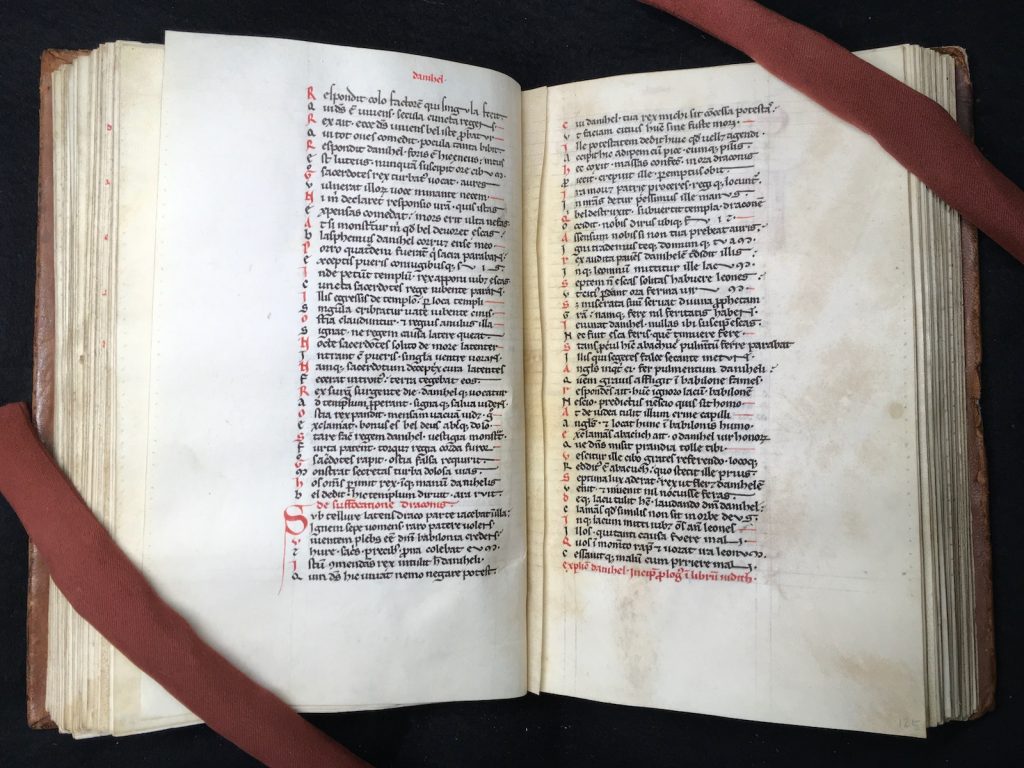

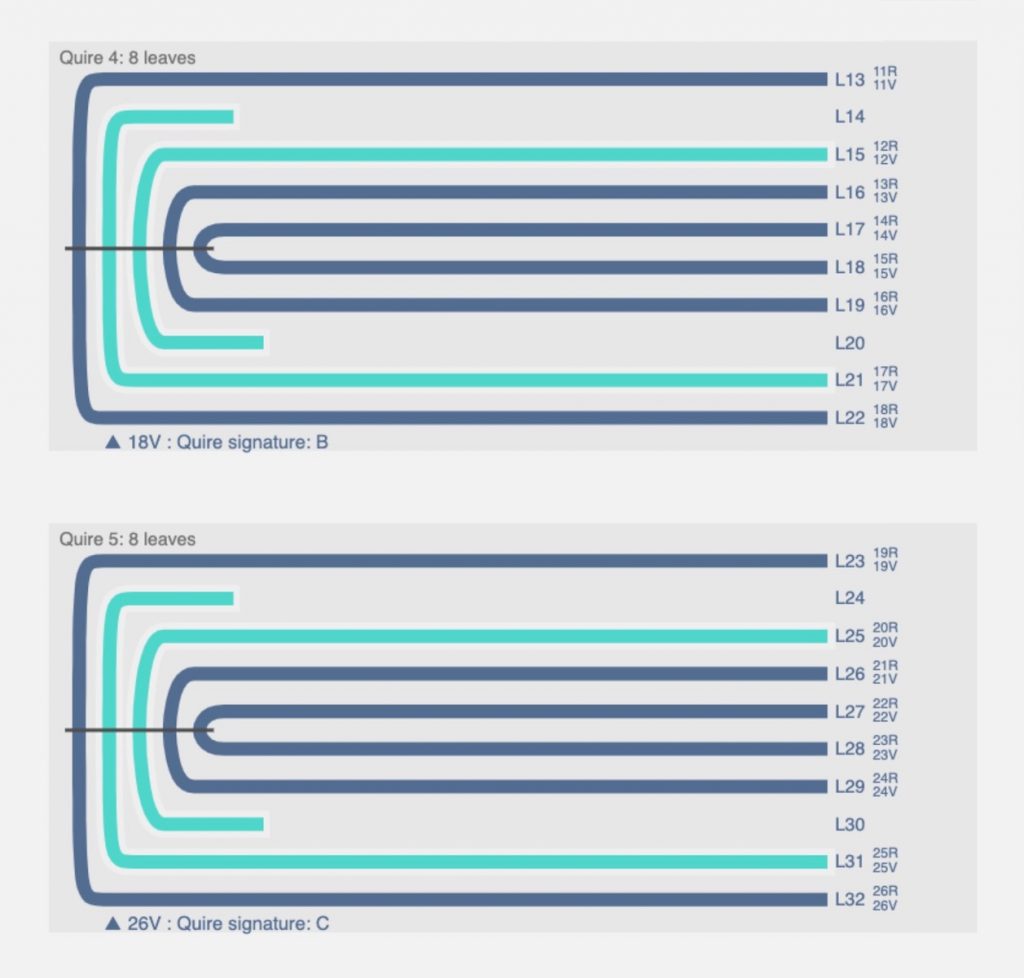

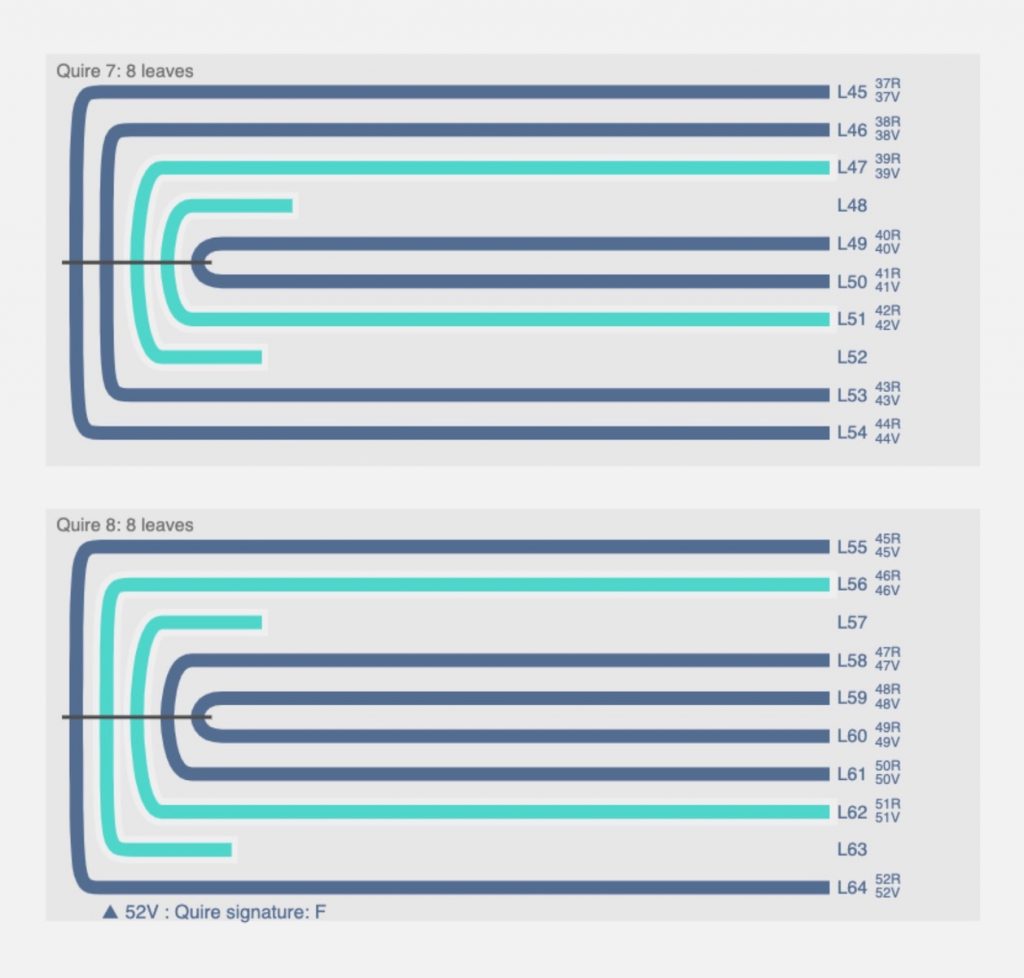

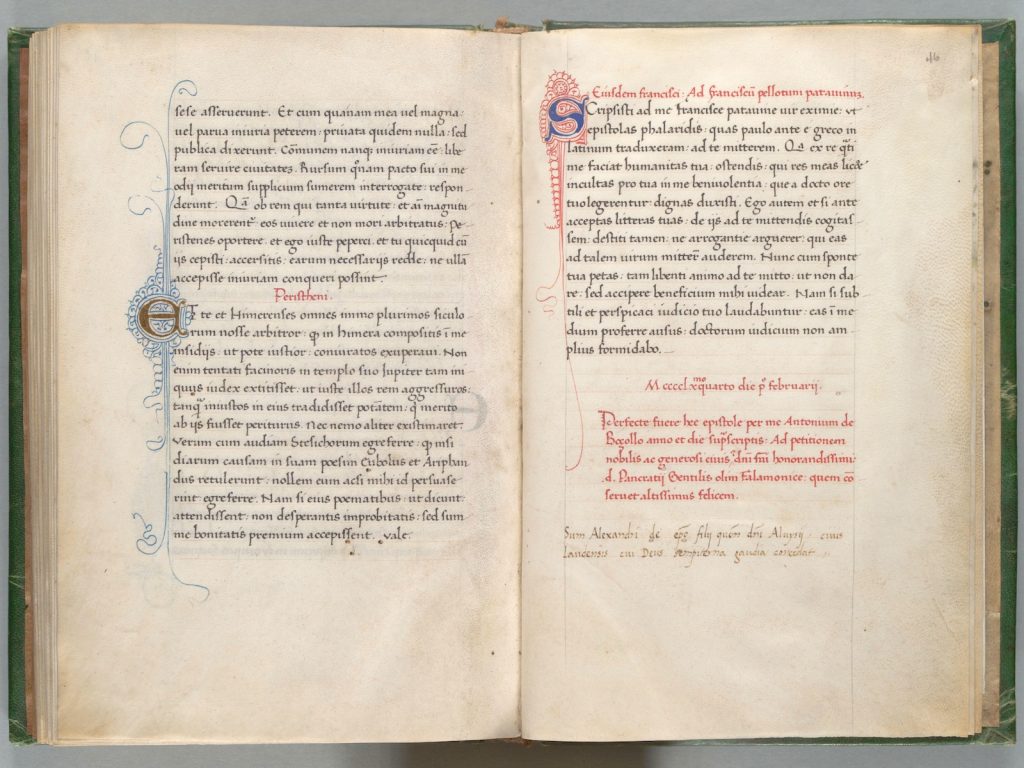

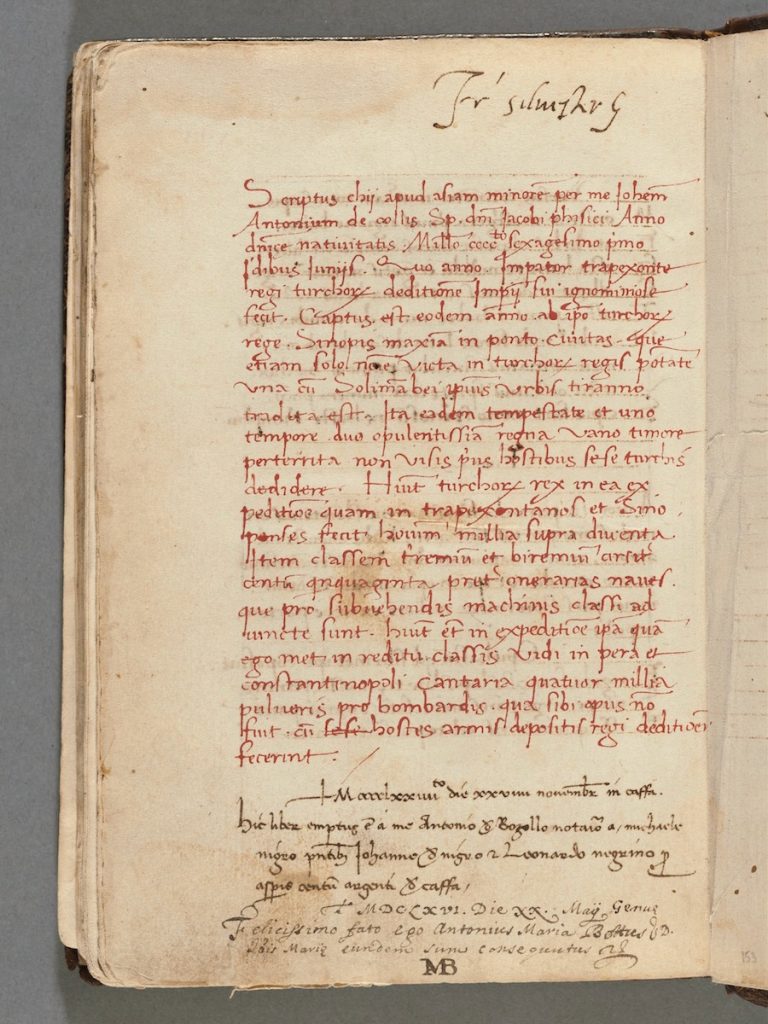

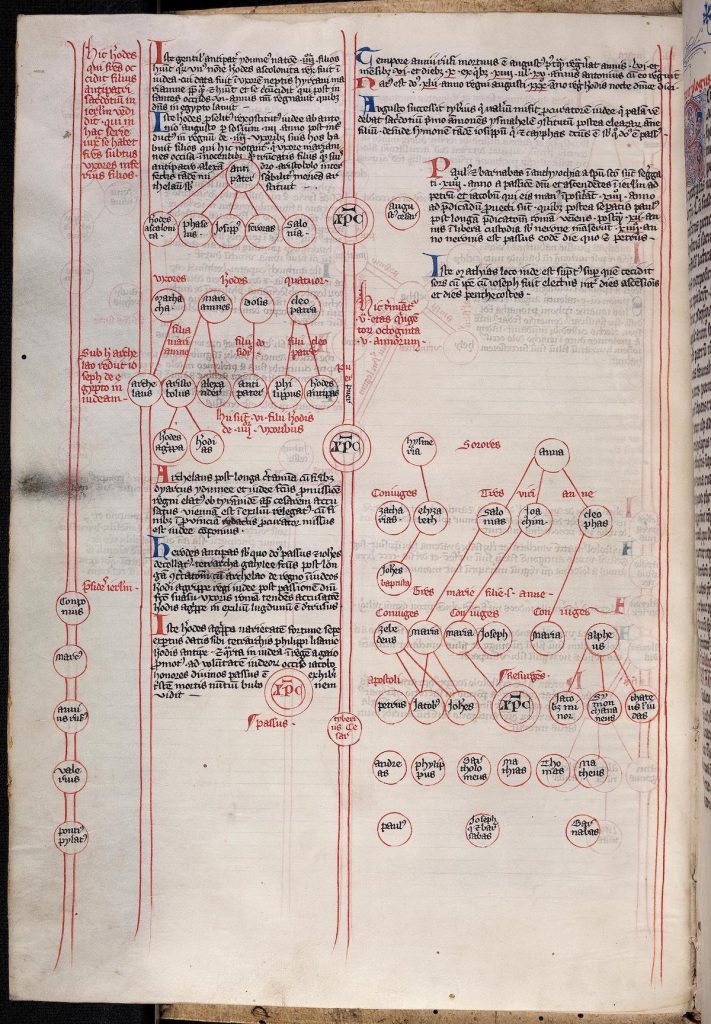

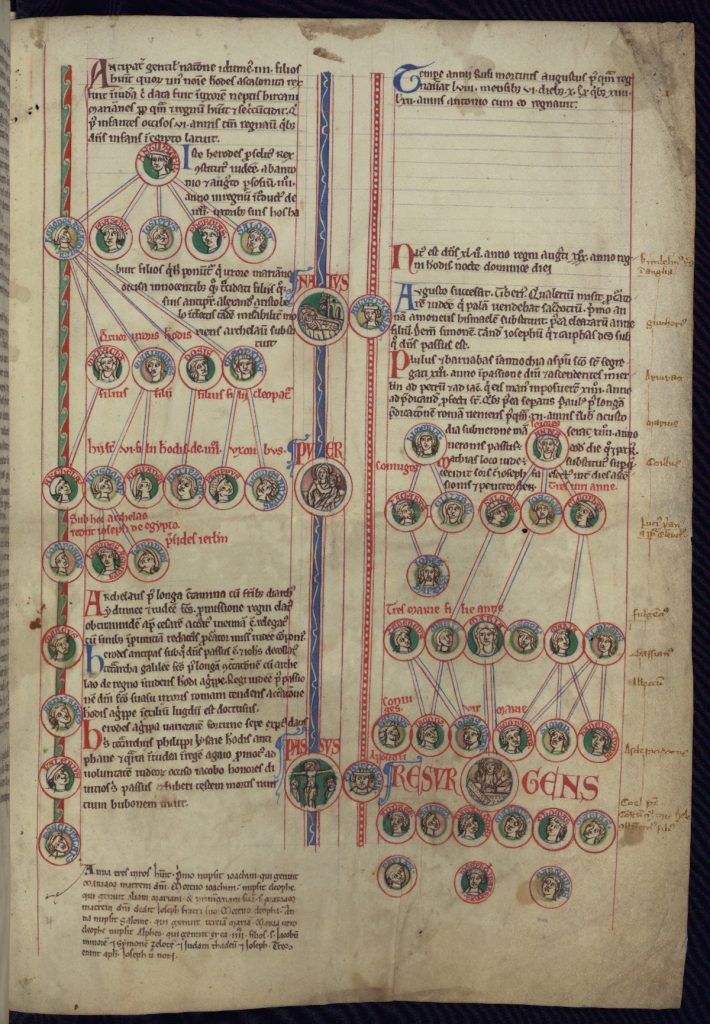

Jean-Baptiste Piggin provides a work-in-progress list that includes over 200 manuscripts that contain the Compendium. Some of these are designed in the form a roll (also called rotulus) that is supposed to be read vertically from top to bottom, which is ideal for the genealogical arrangement of the work and highlights the direct descent of Christ from Adam. Several manuscripts, on the other hand, are in codex format like MS 9/2:29, which, as it stands, consists of only a single bifolium (two conjoint leaves) that contains only part of the text. The Compendium takes up somewhere from 3 to 8 leaves in other codices that are approximately the same size as MS 9/2:29, depending on the layout of the text. Although the narrative and the main points are essentially the same in most witnesses, the decorative program in the manuscripts varies greatly. They all utilize genealogical trees that are linked together with roundels. Yet, while some contain roundels with only names of individuals and mentions of significant events with no illuminations, others are illuminated with busts of historical figures and miniatures of historical scenes.

Folio 2r of MS 9/2:29 contains the final portion of Peter’s Compendium, the sixth age, which begins with the birth of Christ. The life of Christ continues to take up the central space from previous leaves, beginning with the announcement of his birth (“Christus natus”: Christ is born). This is then linked to the infancy of Christ and his crucifixion. The left column commences with the line of Antipater (113-43 BCE), father of Herod I (37-4 BCE), the King of Judea at the time of Christ’s birth. Depicted on the right is Caesar Augustus, the first Roman Emperor, who reigned from 27 BCE until 14 CE, again corresponding to the time of Christ’s birth. This type of parallel narration of events was very common especially in the later Middle Ages, and in the context of the Compendium it serves to place the story of the life of Christ into the broader historical context.

On the right-hand side of folio 2r, we also see the genealogy of the extended family of Jesus, which is known in literature as “holy kinship.” The lineage begins with Hismeria and Anne who are indicated to be sisters (“sorores”). According to this version of the life of Christ, Anne is the mother of Mary and grandmother of Christ. Through her three different marriages (identified as Salome, Joachim and Cleopas in MS 9/2:29) she has three daughters, all called Mary (that is, the virgin Mary, Mary Cleopas, and Mary Salome). Half-sisters of Mary are portrayed as mothers to some of the apostles, which make them direct cousins of Jesus. Anne’s sister Hismeria, on the other hand, is the grandmother of John the Baptist through her daughter Elizabeth. This version of the story of the family of Jesus is thought to have been developed by Haimo of Auxerre (d. approximately 865) in the mid-ninth century and it was prevalent in medieval biblical historiography until it was rejected during the Council of Trent, the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, in the mid-fifteenth century.

As mentioned above, the decorative program in the manuscripts of the Compendium varies greatly. For example, Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Cod. Sal. IX,40, dated to around 1300, does not contain a single illumination even though it does depict a carefully designed genealogical tree. The Walters Art Museum, W.796, dated to the early thirteenth century, on the other hand, is the exact opposite, with each individual person or event mentioned in the genealogical tree not only named but also visualized inside the roundels. In yet other manuscripts, such as Cologny, Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cod. Bodmer 183, certain personages and events are given prominence with much bigger miniatures while the rest of the roundels remain unillustrated.

In the case of the partial genealogical tree surviving in MS 9/2:29, it is seen that not all names or events that are mentioned are chosen as part of the illustration program. The manuscript is considerably more colorful than other manuscripts of the Compendium in charting the genealogical tree as well as featuring a less rigid layout. What is perhaps most striking is the selection and placement of the images. In similar genealogical works from the Middle Ages, including other manuscripts of the Compendium, illuminations, whether they are of persons or events, are usually placed inside roundels. Yet, in MS 9/2:29, a series of illustrated figures are placed atop the roundels. Furthermore, women such as Hismeria and Anne (as well as Abigail on folio 1r) are given visual prominence in line with the narrative, an aspect that is also uncommon in other manuscripts of the Compendium. Not only do these decorative choices set this manuscript apart, but the gaze and the powerful gestures of these illustrated figures as they are depicted in MS 9/2:29 also create a more dynamic reading of the text.

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from Bernard M. Rosenthal Inc. in July 1975, and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

- You can read more about Peter of Poitiers and his works including the Compendium in Philip S. Moore. The Works of Peter of Poitiers, Master in Theology and Chancellor of Paris (1193-1205). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame, 1936. [public domain]

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.