Spencer Research Library and Archaeology

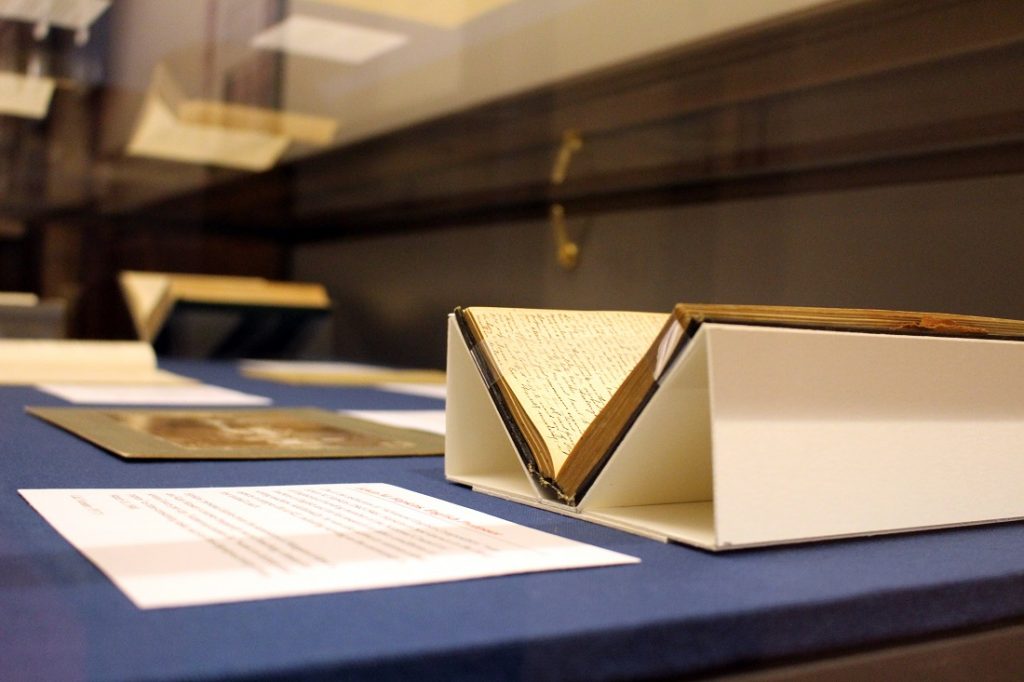

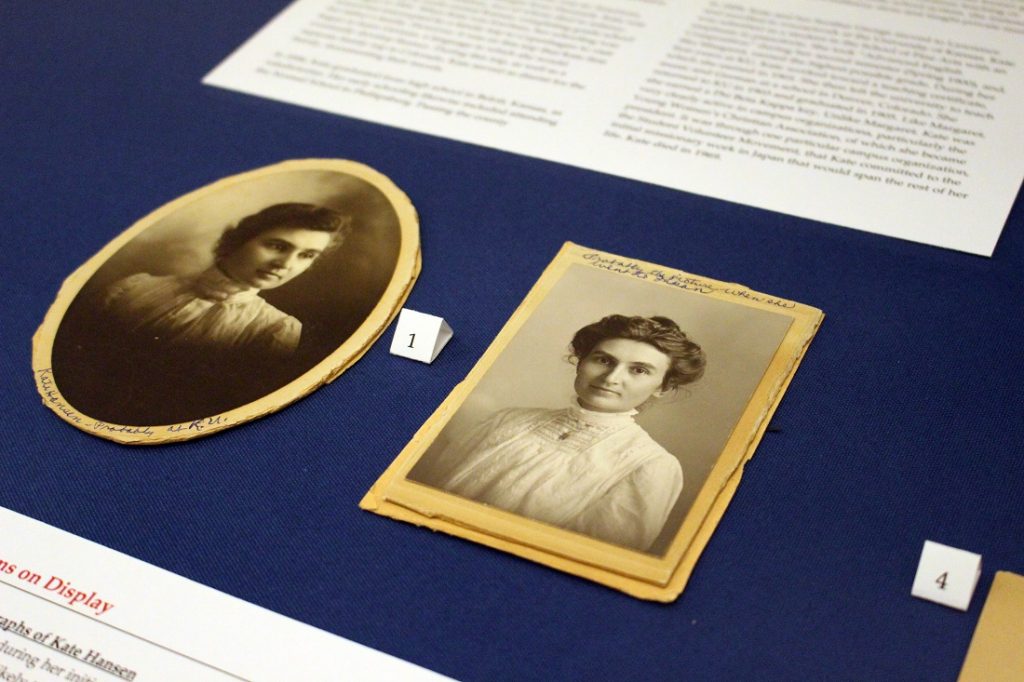

February 19th, 2019This month’s temporary exhibit in Spencer’s North Gallery – titled “Spencer Research Library and Archaeology” – features a collection of materials available through Spencer that could or have proven to be useful in archaeological research. Spanning from tomes written during the developmental days of archaeology as a science to modern articles on the forefront of archaeological investigations, the collections at Spencer Research Library offer a broad assemblage of knowledge not available through most library settings.

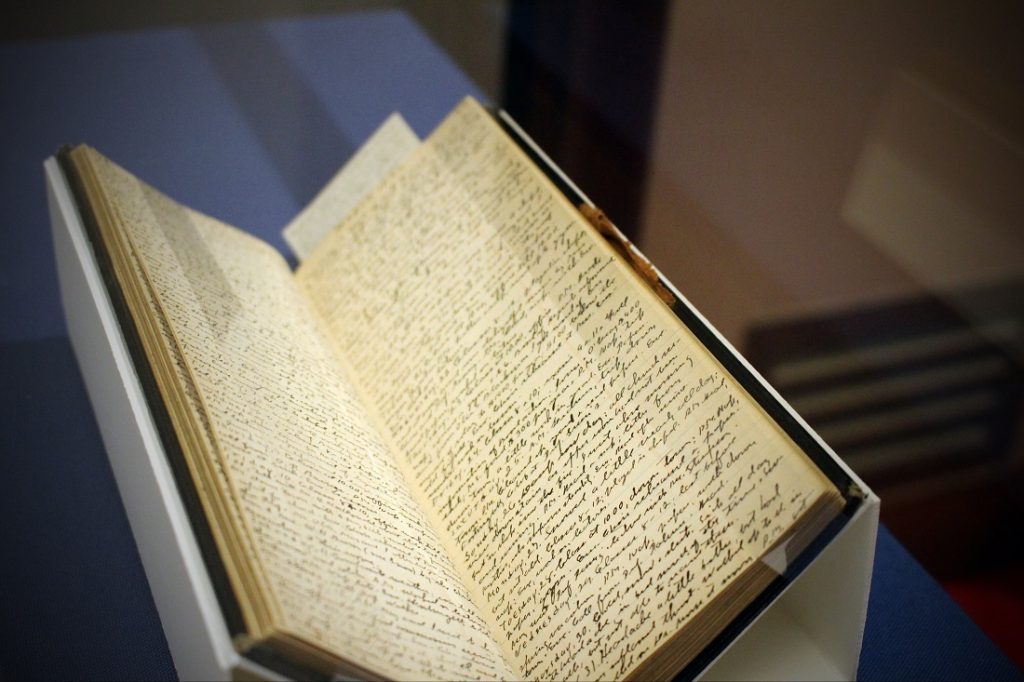

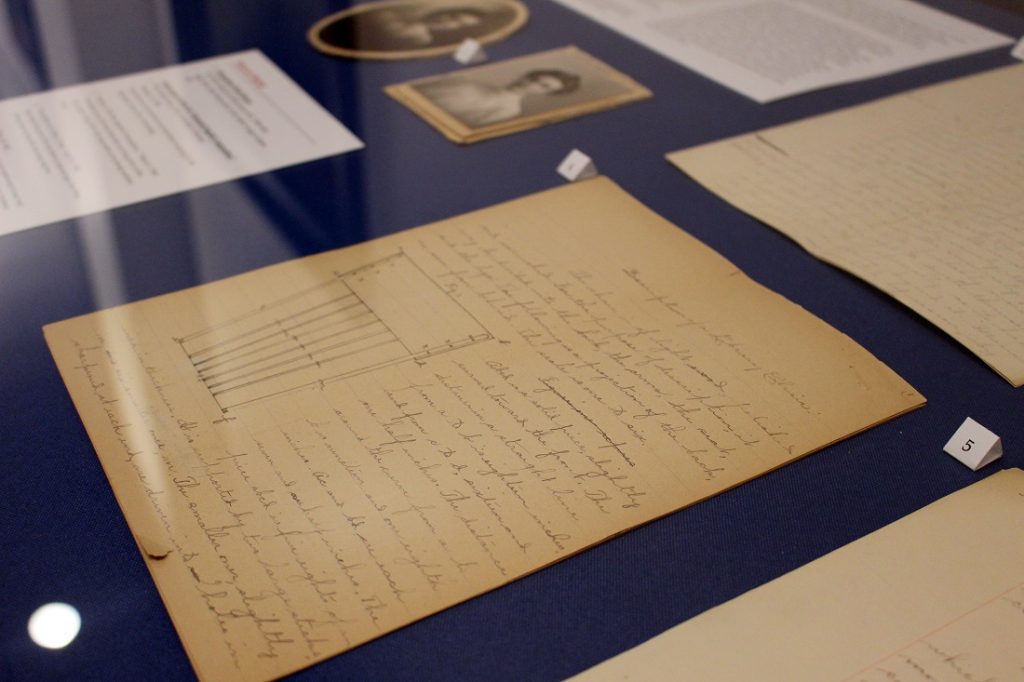

The first display case demonstrates the spectrum of resources available to archaeological researchers by highlighting a sample from each of Spencer’s collections. This includes documents of early Old World archaeology, books on regional archaeology, archaeological reports, and serial clippings and publications featuring archaeological findings and collections. Such materials are often used as supplementary materials in extant studies, though there is plenty potential for new studies to be conducted as well.

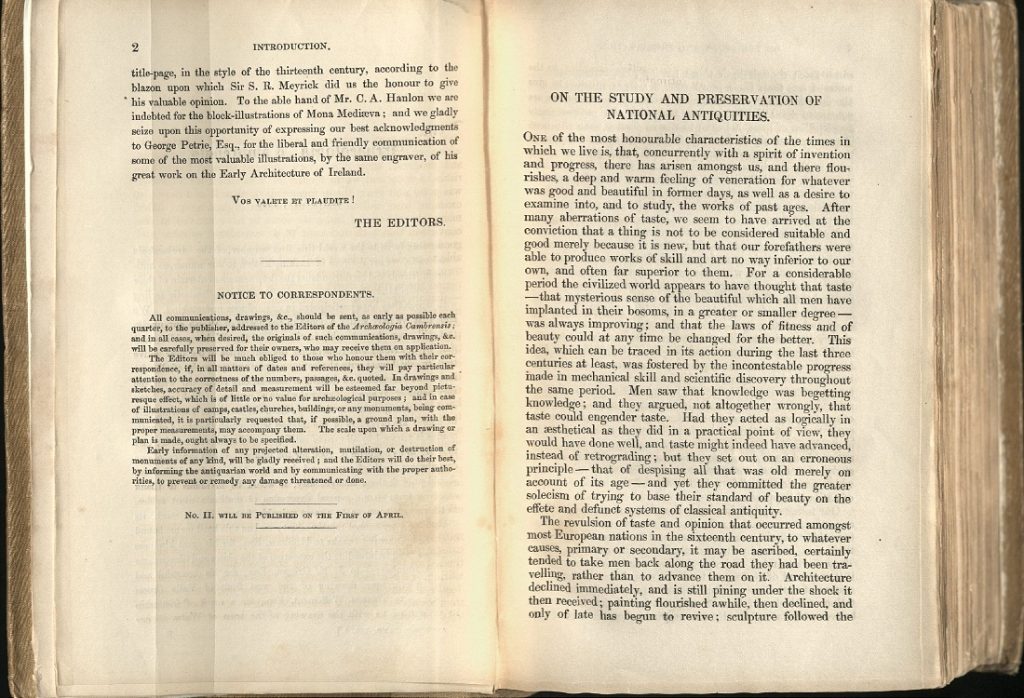

Archaeologia cambrensis (Welsh Archaeology), volume 1, number 1, January 1846.

Published by the Cambrian Archaeological Association with the goal of interpreting cultural significance

over material value, Archaeologia cambrensis illustrates a transitional period

in the development of archaeology as a science. Call Number: C16530. Click image to enlarge.

Kansas Archaeology, 2006. This work offers a broad perspective of the

archaeological history of Kansas. It is accessible to those with or without a

strong background in archaeology. Call Number: RH C11685. Click image to enlarge.

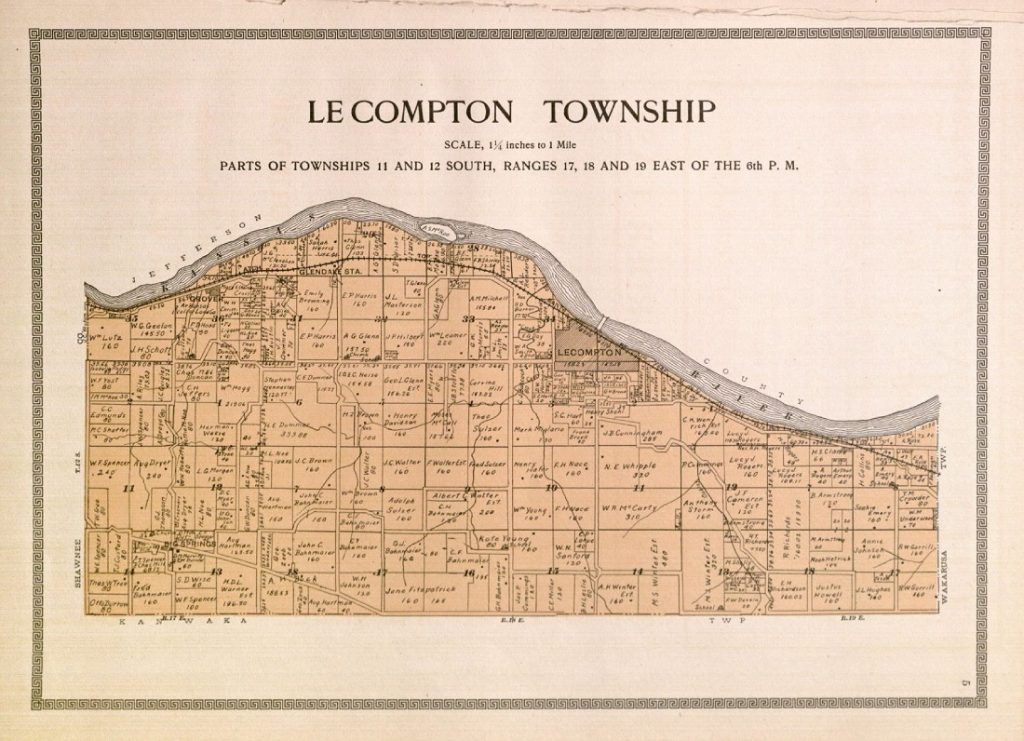

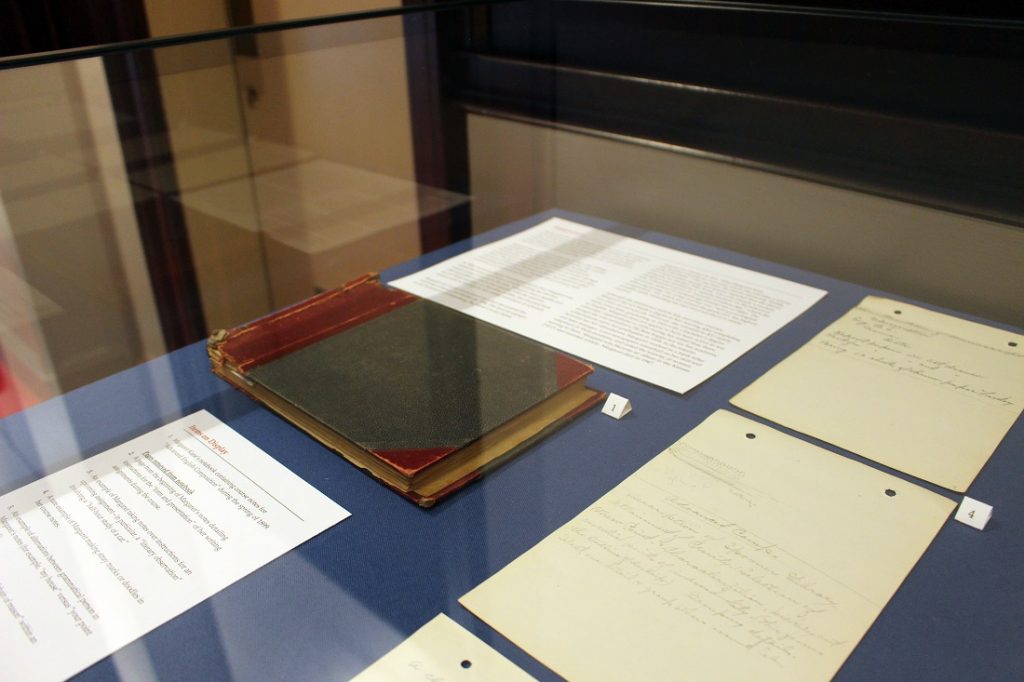

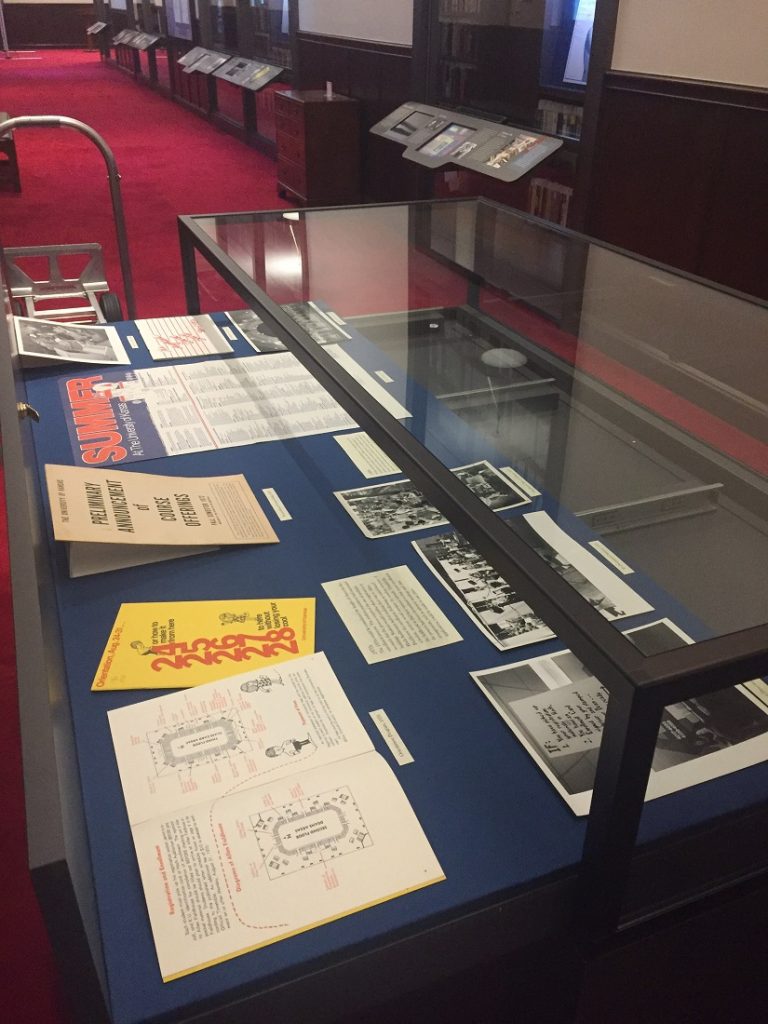

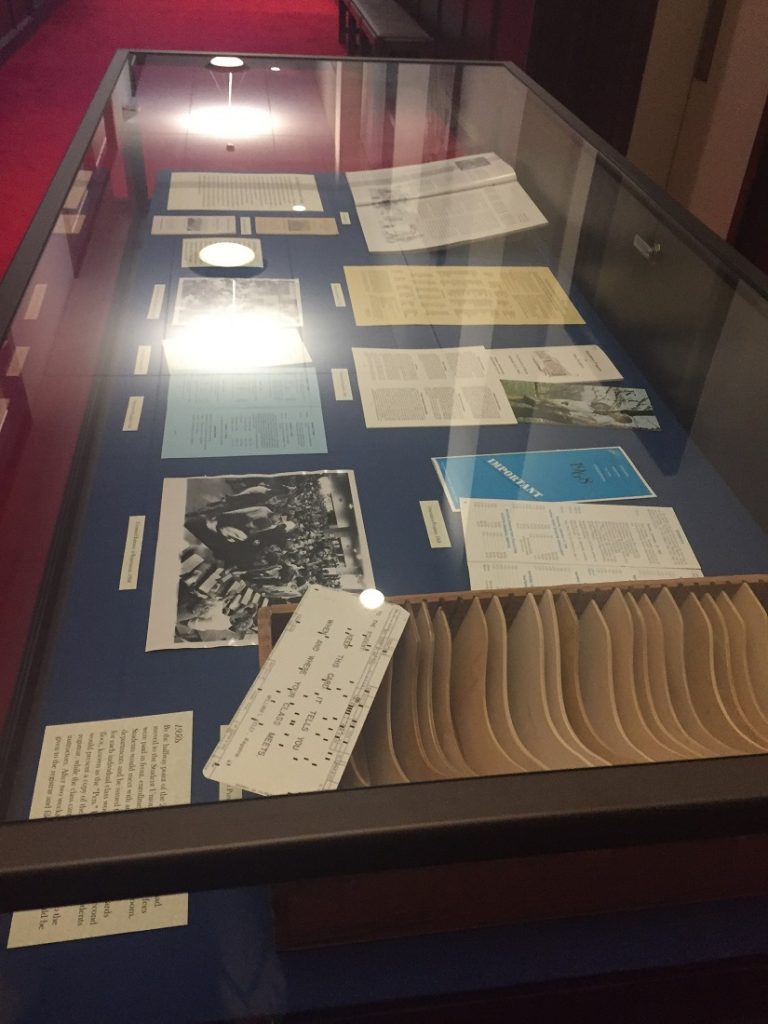

The second display case features materials available at Spencer Research Library that have been used in archaeological projects. One such project is the Douglas County Cellar Survey, known colloquially as the “Caves Project.” The Caves Project is a survey funded by the Douglas County Natural and Cultural Heritage Grant Program with the goal of locating and documenting stone arched cellars. The cellars (referred to as “caves”) – constructed from the 1850s into the 1920s – represent a cultural phenomenon unique to the region; thus, archaeologists hope to properly document these caves before they are lost to time. The Caves Project has utilized Spencer Research Library materials such as plat maps, deed records, and topical books on regional history.

Plat map of Lecompton Township in Plat Work and Complete Survey of Douglas County, Kansas, 1909.

This map was used in the Caves Project to locate potential cave structures. In addition to

revealing site locations, the map was also superimposed with older plat maps of the same area to

indicate images that were no longer extant. Call Number: RH Atlas G32. Click image to enlarge.

Also included in the second display case is an artifact, known as a projectile point base, that comes from the Clovis Paleoamerican culture of North America. Likely a broken spear tip, this artifact is likely around 13,000 calendar years old. Found during a 1976 pedestrian survey of site 14DO137 near Clinton Lake in Douglas County, Kansas, this point base is one of the only remaining items left by some of – if not the – first people to ever walk in eastern Kansas. Reviewed as part of an ongoing survey of literature for the Caves Project, multiple archaeological reports indicated that the point was donated to the University of Kansas Archaeological Research Center. Thanks to their cooperation, the point has been loaned to Spencer Research Library for this current exhibit and, as seen below, three-dimensionally scanned. The point has been used in a number of archaeological investigations, including a report on the presence of Clovis people in southeastern Kansas by KU’s Dr. Jack Hofman.

https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/14do137-02823a31be3c479291888da220191b9a

Frank Conard

Spencer Research Library Public Services Student Assistant and KU Anthropology Major

Viagra is a world-renowned brand that helps millions of men worldwide – Buy Viagra without a prescription in the USA