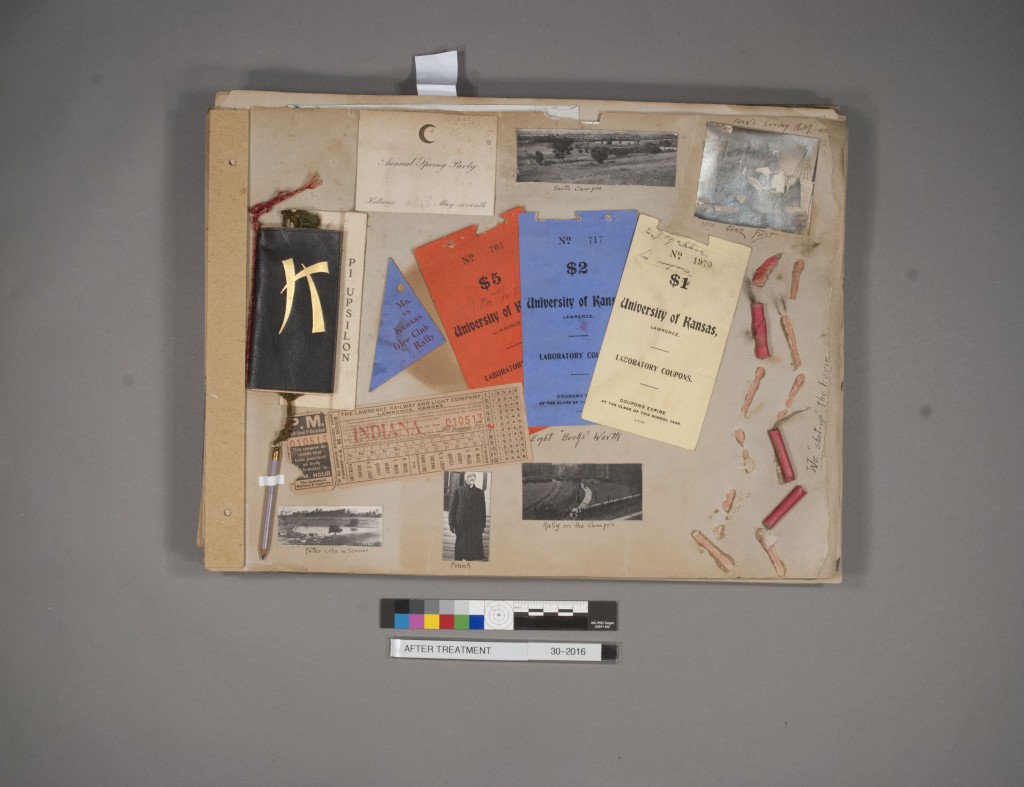

Around the time of our Care and Identification of Photographs workshop here at Spencer, I had four photographs from the John W. Temple Family Papers on my bench in the lab for cleaning and rehousing. The timing was fortunate for me, because from the workshop I picked up some tips for housing these items, and I also learned about the unique process by which two of the prints were created.

The photographs arrived, as so many of their age and type do, in precarious condition: two medium-format portraits were housed in heavy, dusty frames that were held together with brittle nails, and two military panoramic photographs were mounted to brittle, acidic boards. All of the photographs had varying degrees of surface dirt and apparent water staining, and had sustained some amount of physical damage caused by their housings and mounts. Before they could be safely handled and described by processing archivists, it was necessary to stabilize their condition and provide them with protective housings.

The two panoramas, which depict Troop D of the 9th Cavalry during the time of John Temple’s service in the Spanish-American War, were mounted to boards about two inches larger on all sides than the prints themselves. One board had a large loss along one edge and the other had a long vertical break in it that was causing the photograph to tear. Rather than removing the photographs from the backing entirely (a time-consuming and rather harrowing process), I trimmed the mounting board close to the edges of the photographs to reduce the potential for further breakage. I also cleaned the photographs with polyurethane cosmetic wedge sponges, which are gentle on the delicate emulsion surface. I then created a folder of archival corrugated board fitted with pieces of 1/8” archival foam to hold the photographs snugly in place, leaving spaces to allow them to be removed if necessary. The foam is firm enough to support the photographs but will not abrade the fragile edges.

Panoramic photographs of 9th Cavalry, Troop D, circa 1898.

John William Temple served in this unit during the Spanish-American War.

Photographs shown in housing with foam inserts.

John W. Temple Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS-P 1387 (f).

Click image to enlarge.

Detail of panoramic group portrait of Troop D of the 9th Cavalry

(with adorable canine companion), circa 1898. John W. Temple Family Papers.

Call Number: RH MS-P 1387 (f). Click image to enlarge.

The two portraits were in more fragile condition and therefore needed a few more layers of protection than the panoramas. They depict Fred Thompson, and a young Pearl Temple, wife of John W. Temple. With the curator’s and archivist’s consent, I removed the frames; the frames’ backings were loose and unsealed, which made removal easy, but the portraits were covered in surface dirt that had made its way in through the unsealed backings. I cleaned the portraits as I had the panoramas, with soft cosmetic sponges. Each portrait is mounted to a thin board, and I again considered but ultimately rejected the idea of removing the mounts. Even though past water damage has caused the portraits to warp slightly, they were stable enough once removed from the frames.

To house the portraits, I first affixed the portraits to sheets of mat board using large archival paper corners as shown in the photos below. The corners gently hold the photographs in place to prevent shifting, and they can be easily unfolded to allow for viewing or removing the items. Such corners are often used in photograph and art conservation and framing, but they are usually small and discreet and not as generously sized as these. Because the main purpose of this housing is to protect the portraits, I made these corners extra-large to distribute any stress on the photograph edges. Next I hinged window mats to the lower mat boards and lined the inside of the window mats with the same thin foam I used in the panorama housing, again to prevent abrasion of the photograph surfaces. Finally I added a front cover of mat board, and placed all three of the housings together in a flat archival box.

Two undated historic portraits in their new housings:

Fred Thompson (left) and Pearl Temple (right).

John W. Temple Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS-P 1387 (f).

Click image to enlarge.

Detail of paper corners, closed to secure photograph (left) and

open to allow access (right). Pearl Temple portrait, undated.

John W. Temple Family Papers.

Call Number: RH MS-P 1387 (f). Click image to enlarge.

Photograph housing with foam-lined window mat.

Fred Thompson portrait, undated. John W. Temple Family Papers.

Call Number: RH MS-P 1387 (f). Click image to enlarge.

Completed photograph housings in a flat archival storage box.

John W. Temple Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS-P 1387 (f). Click image to enlarge.

When I first began working on the portraits, I noticed evidence of retouching on the images – a common practice. During the photograph identification workshop, I learned that this type of portrait is called a crayon enlargement, and that they were popular in the early twentieth century. In a crayon enlargement, the photographer uses a smaller photograph, often a cabinet card, to make an enlarged print that is usually slightly underexposed, and then adds hand-drawn or painted touches to the enlargement. The result can be subtle, as in our two portraits here, or so heavily augmented as to be difficult to identify as a photograph.

Both of these portraits are probably gelatin silver prints; the neutral tone and silver mirroring on Fred’s photograph point to that process (Pearl’s photograph was probably sepia toned to give it its warm color). In Pearl’s portrait, the embellishments are limited to a few brushstrokes accentuating features of her face and ruffles in her dress. There is also a patterned background that was probably created with an airbrush and stencil. To the naked eye these are the only additions, but under magnification (our workshop fee included a super handy handheld microscope) it’s possible to see pigment droplets throughout the image, indicating more airbrushing.

Detail of hand-drawn embellishments on the portrait of Pearl Temple.

Note the brushstrokes under mouth and nose and along ruffles in clothing.

John W. Temple Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS-P 1387 (f). Click image to enlarge.

The accents made to Fred’s portrait are more extensive. Because the enlargement would have been underexposed, the details in light areas would have been lost, so the photographer has used airbrush and stencil to recreate the washed-out tie and collar, and also to darken the background. As in Pearl’s portrait, pigment drops are visible throughout the image under magnification, even where it doesn’t appear at first look.

Detail of airbrush accents to shirt and tie on portrait of Fred Thompson.

John W. Temple Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS-P 1387 (f). Click image to enlarge.

With the housing complete, these photographs are ready for processing and will soon be added to the finding aid for the collection. It was such a pleasure to work on these wonderful portraits; not only are they lovely objects, but I always love a good housing challenge, and seeing examples of this historical photographic process so soon after learning about it was a happy and instructive coincidence.

Angela Andres

Special Collections Conservator

Conservation Services