Brian Aldiss, 1925-2017

August 31st, 2017On August 19th, science fiction writer and critic Brian Aldiss died, a day after turning 92. In an obituary for The Guardian, fellow writer Christopher Priest characterized Aldiss as “by a long chalk the premier British science fiction writer.” As fans and scholars of speculative fiction around the world mourn this loss, some will be surprised to discover that part of the British writer’s literary legacy resides in Kansas: the Spencer Research Library a holds significant collection of papers for Aldiss, including materials for his Billion Year Spree and his Helliconia Trilogy. The trilogy, which consists of the novels Helliconia Spring (1982), Helliconia Summer (1983), and Helliconia Winter (1985), is among Aldiss’s most admired works. “This depiction of a world that circles a double star, where an orbital Great Year lasts long enough for cultures to emerge, prosper and fail,” Priest writes in his remembrance of Aldiss, “is a subtle, deeply researched and intellectually rigorous work.”

Brian Aldiss accepting the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for best science fiction novel for Helliconia Spring (1982) in Lawrence, KS in 1983. Call number: RG 0/19: Aldiss, Brian

The collection of Aldiss’s papers at KU provides a wealth of evidence for the research and rigor that went into his writings. The 25 boxes of materials for the Helliconia Trilogy include, for example, Aldiss’s extensive correspondence with scientists and scholars to determine the scientific basis for the world he was creating. Those consulted include Iain Nicholson of Hatfield Polytechnic Observatory on the subject of astronomy, Peter Cattermole of the University of Sheffield on geology and climate, and Tom Shippey, then at the University of Leeds, on the languages of the novel. The result is a world striking in its attention to detail.

![]()

A selection of research correspondence with Iain Nicholson, Peter Cattermole, and Tom Shippey concerning the creation of Helliconia. Brian Wilson Aldiss Papers. Call #: MS 214: A.

Not only do these letters reveal the extent to which technical and scientific matters underpin the trilogy’s concept, plot, and themes, but they also offer lighter moments of humor between on-going collaborators. Aldiss, for example, begins a June 1981 letter to Cattermole by quipping, “Helliconian scholars have failed to study Helliconia’s sister planets in any depth; they have been too busy drinking the whisky out of their orrerys.” (MS 214:Aa:2:14a). Writing again to Cattermole in September of 1982, following the publication of Helliconia Spring earlier that February, Aldiss reports,

Vol. 1 has been very well received, especially in the States; over here there were complaints, as you say, about names. Well, it’s no good building up an intense winter atmosphere in Embruddock and then call[ing] the sods Joe and Charlie. There will be more complaints of that nature with Vol II, where I have a vast character list, with over fifty speaking parts, but I see no way of evading the problem and so forge on hopefully. Wait till you meet Queen MyrdalemInggala….. (MS 214Aa:2:16b)

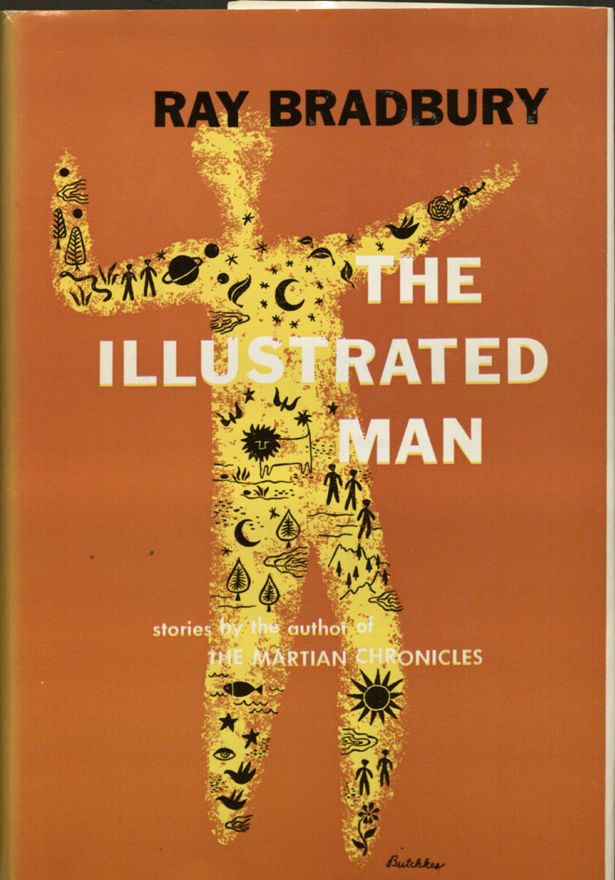

Spencer Research Library’s collections also include manuscript materials for Aldiss’s groundbreaking Billion Year Spree (1973), subtitled “The True History of Science Fiction,” which he later expanded with David Wingrove into Trillion Year Spree (1986). The volume argues for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) as the birth of science fiction.

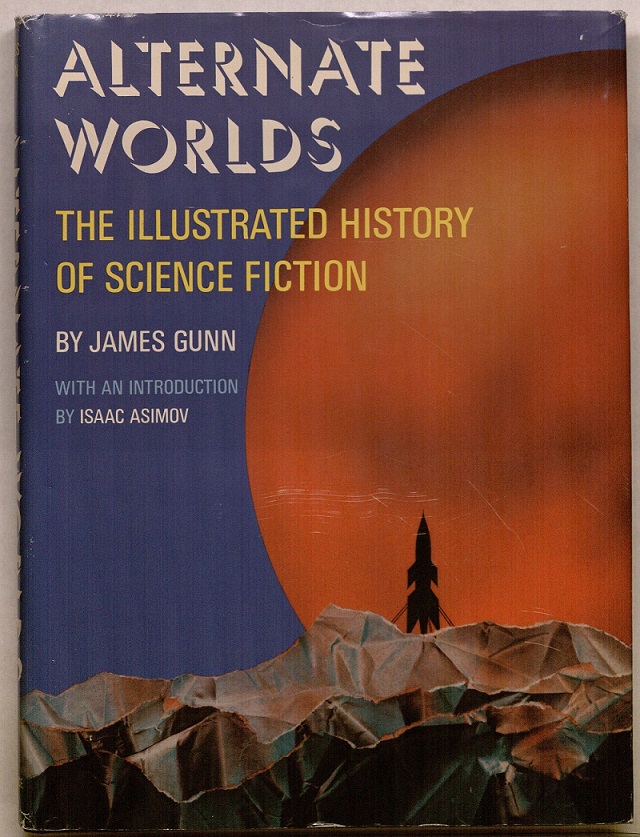

Aldiss’s ties to the University of Kansas grew out of his relationship with fellow science fiction writer and critic, James Gunn, Professor Emeritus of English and the founder of KU’s Gunn Center for the Study of Science Fiction. “We were long-time friends, although an ocean between us limited our encounters,” Gunn explains.

I was a guest in his Oxford home for a couple of days after the founding of World SF in Ireland [in 1976], and he was a guest in my home during his author’s visit here. We were competitors only in the writing of science-fiction histories. We both started in 1971, but circumstances (and maybe the complexities of illustrations) held up Alternate Worlds (1975) [Gunn’s illustrated history of SF] for a couple of years. When I wrote him for a photograph, he suggested that we exchange blurbs–that I would say his history was the best and he would do the same for mine.

Though the delay in the publication of Gunn’s Alternate Worlds meant that the exchange of blurbs never came to pass, researchers can explore both Aldiss’s and Gunn’s processes in writing their respective histories of science fiction by examining the collections of their papers at Spencer Research Library.

Left: Brian Aldiss’s Billion Year Spree (1973). Schocken paperback edition, second printing. New York: Schocken Books, 1975. Call #: ASF B1245. Right: James Gunn’s Alternate Worlds. First edition. Englewood Cliffs, N.J : Prentice-Hall, 1975. Call #: E2598.

In his introduction to Billion Year Spree, Aldiss mused, “Possibly this book will help further the day when writers who invent whole worlds are as highly valued as those who re-create the rise and fall of a movie magnate or the breaking of two hearts in a bedsitter. The invented universe, the invented time, are often so much closer to us than Hollywood or Kensington.” Thank you for those invented universes, Brian Aldiss.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian

![Image of Wonder Stories' form rejection letter for Wollheim's "The Second Moon", [1933]](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/MS_250_b4_f8_form1.jpg)

![Image of Wonder Stories' form rejection letter for Wollheim's "The Discovery of the Martians", [1933].](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/MS_250_b4_f8_form2.jpg)

![Detail from Wonder Stories' form rejection letter for Donald A. Wollheim's Story "The Second Moon," [ca. 1933]](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/MS_250_b4_f8_form1_detail.jpg)