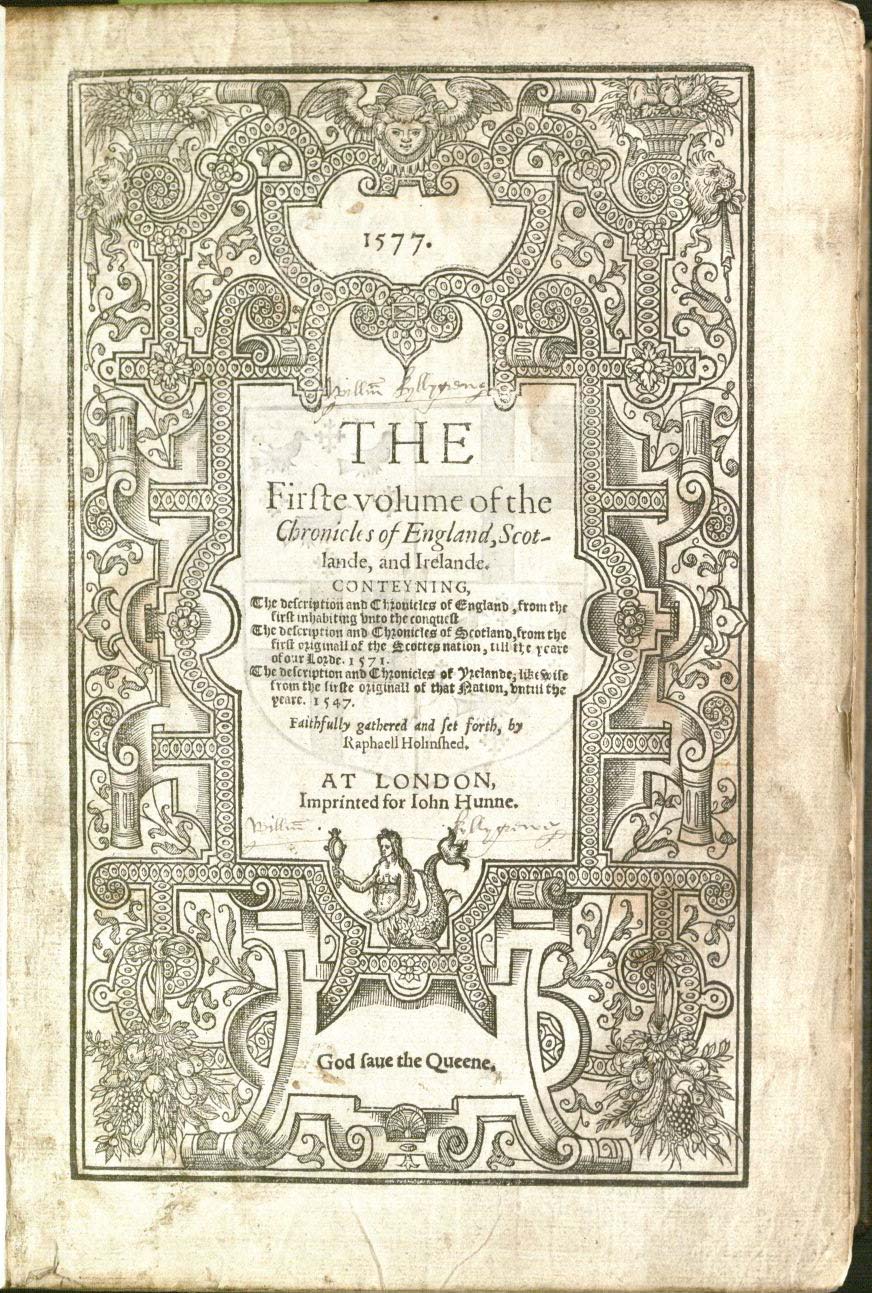

Manuscript of the Month: A Sixteenth-Century Copy of the Life of Cardinal Dominicus Capranica

January 28th, 2020N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with. The current KU Library catalog records (linked below) will be updated in accordance with her findings.

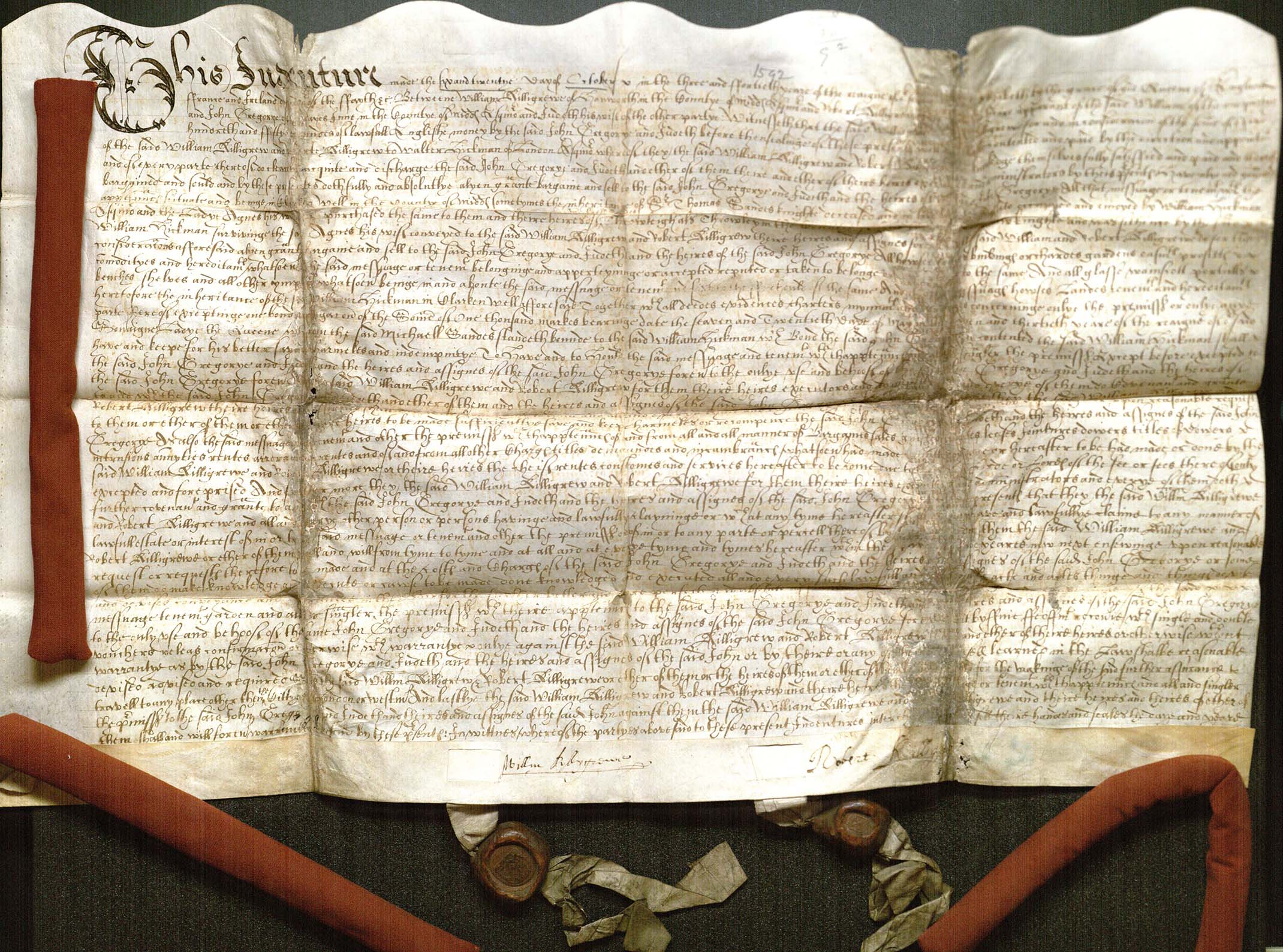

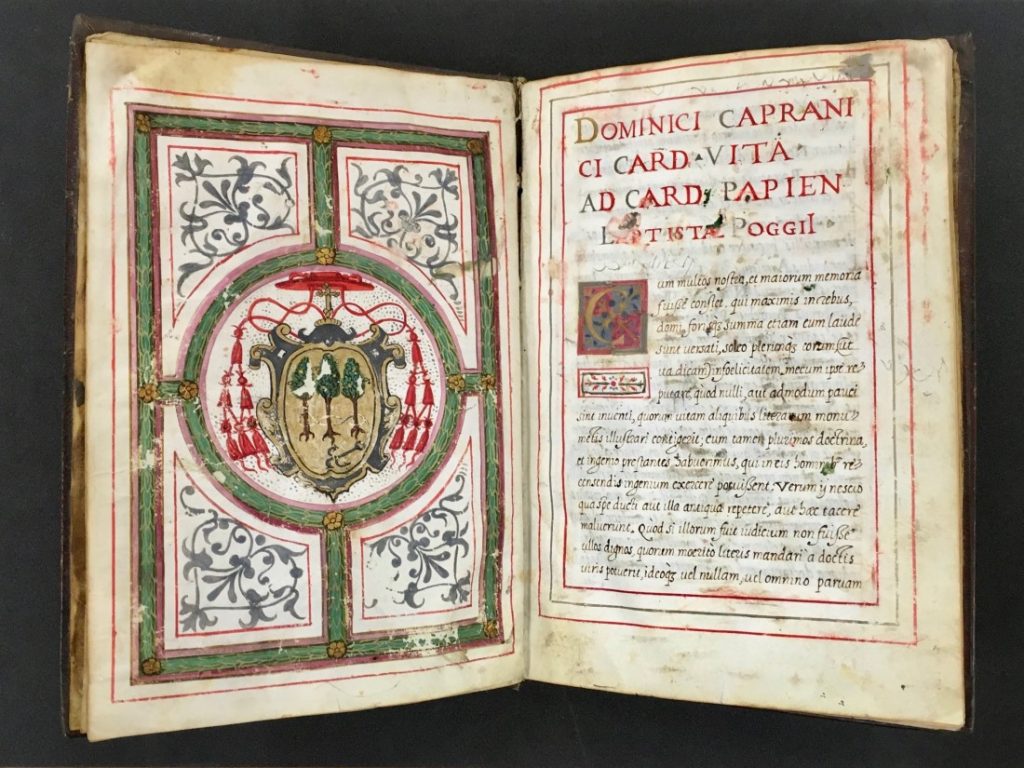

Kenneth Spencer Research Library, MS C247 is a thin parchment manuscript that was produced in the middle of the sixteenth century. It consists of 38 parchment leaves and contains a single text written in Humanistic cursive script by an unknown scribe: the Vita Capranicae [lit. Life of Capranica] by Giovanni Battista Bracciolini (1440–1470). A biography of Cardinal Dominicus Capranica (1400–1458), the Vita Capranicae is thought to have been composed in 1460s, shortly after the Cardinal’s death in 1458. The author of the biography, Giovanni Battista Bracciolini, was the second son of the renowned Italian humanist Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459) and personally knew Cardinal Capranica; therefore, the biography is thought to be partly based on his first-hand knowledge and observations. The Vita Capranicae was first edited and published under the title Cardinalis Firmani vita in 1680 by Étienne Baluze (1630–1718) as part of his Miscellaneorum Liber Tertius. In this first edition, the text was divided into twenty-seven chapters and was misattributed to another Battista Poggio from Genoa. Over the centuries, the Vita Capranicae also was sometimes mistakenly attributed to Poggio Bracciolini himself and not to his son, as is the case in the older records of the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

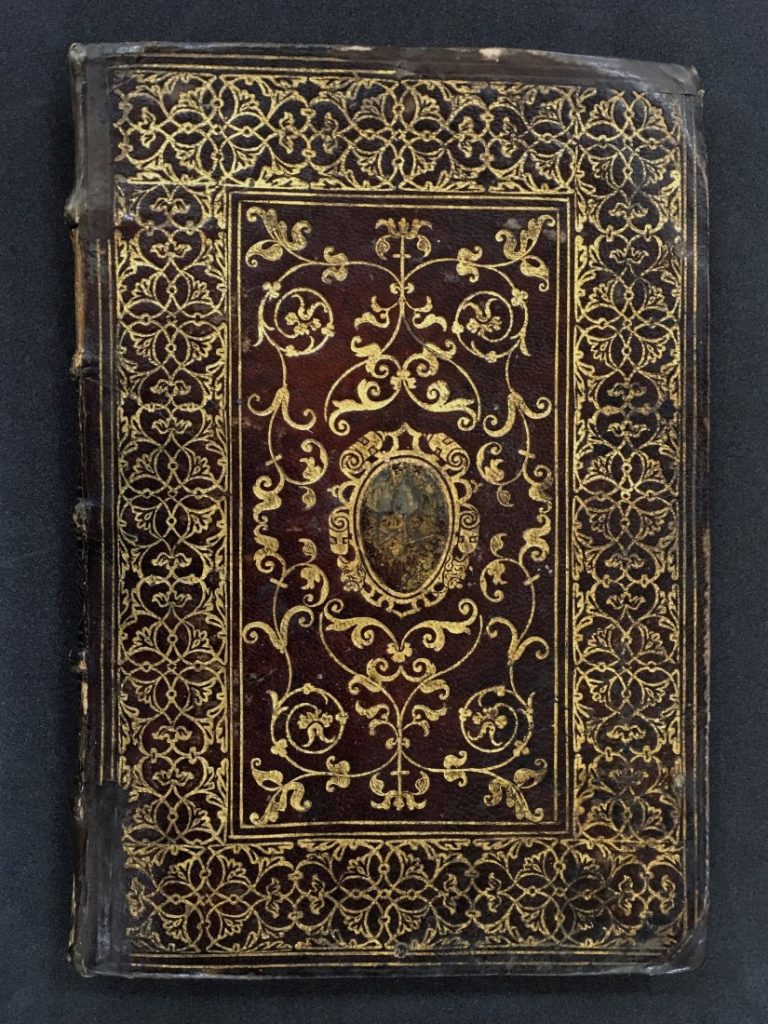

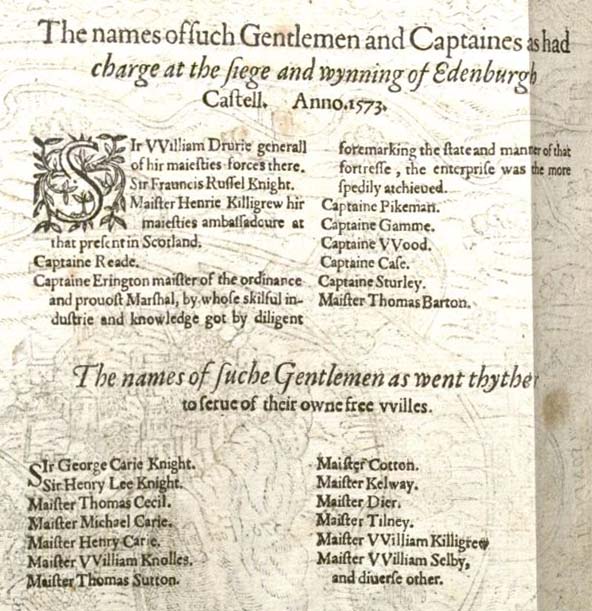

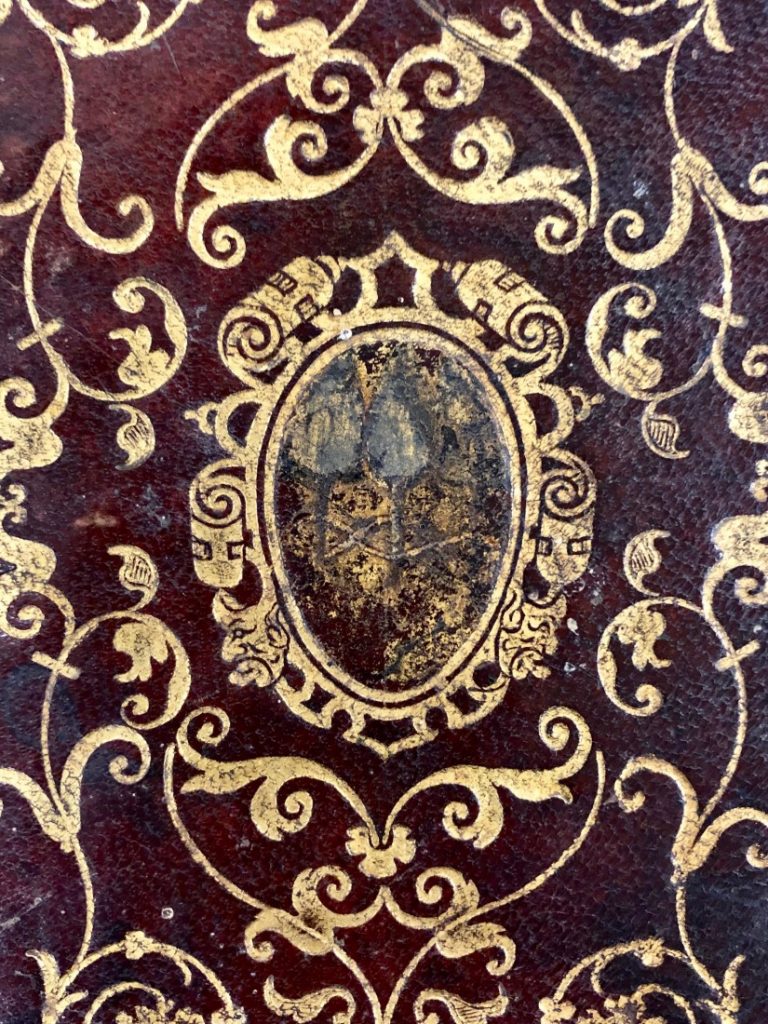

In MS C247 the text is preceded by a decorated frontispiece on folio 4v with the coat of arms of Dominicus Capranica. The coat of arms is charged with an anchor tied to a hawser intertwined around three uprooted Cypress trees on a golden field and adorned with a cross bottony and a red galero with six tassels in three rows on each side. The binding of the manuscript is contemporary to the copying of the text, possibly original. Based on stylistic features, it can be dated to the mid-sixteenth century like the text itself and was probably made in a workshop in Rome, Italy. In addition to delicate gold-tooling, the dark red leather binding also features the painted shield of Dominicus Capranica at the center of both covers.

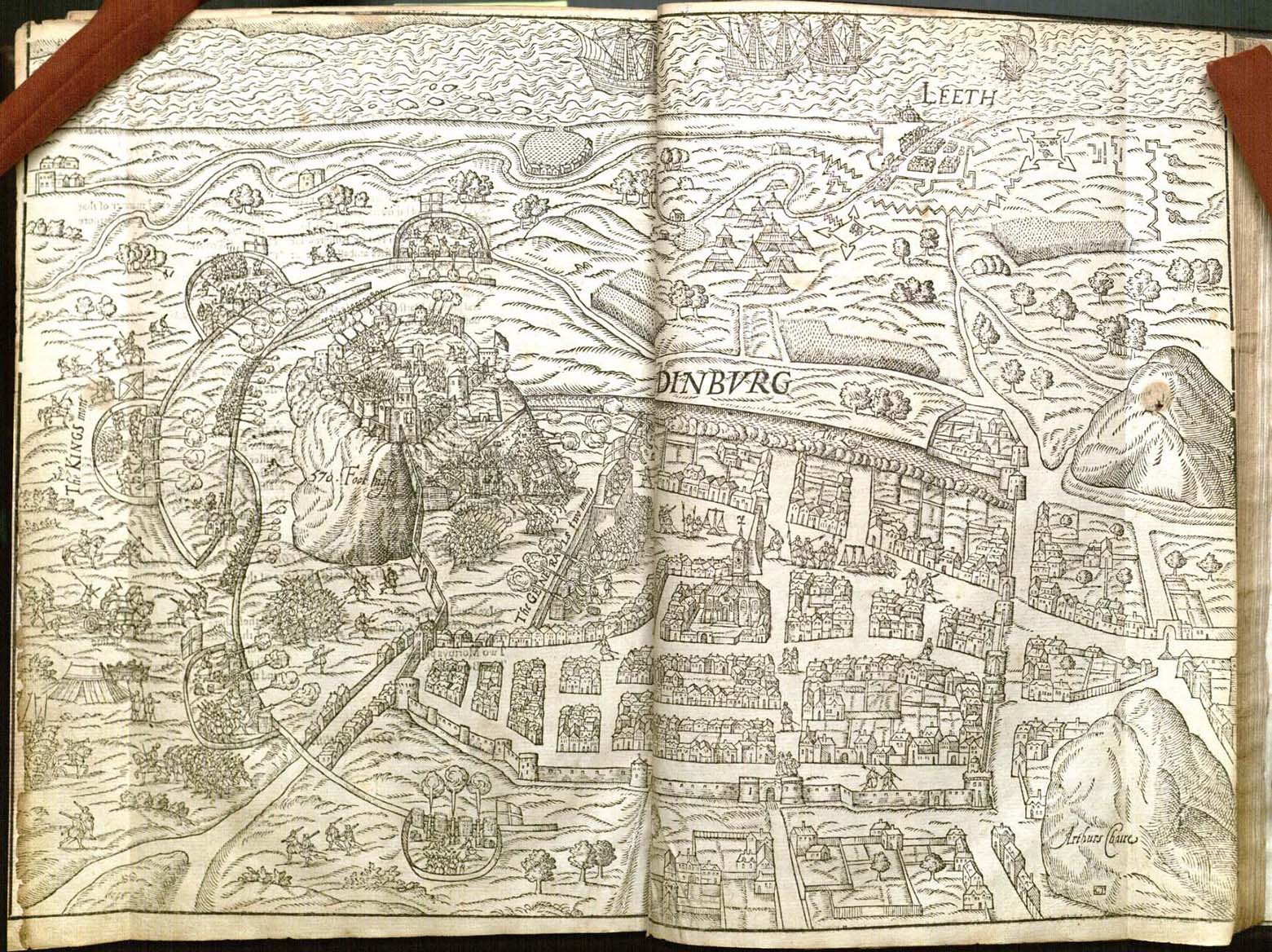

According to Ruut Kataisto, there are only nine surviving manuscripts containing the Vita Capranicae, one of which is Kenneth Spencer Research Library, MS C247. Even though it is not the earliest witness to the text, this is one of two manuscripts written on parchment (the other being Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. lat. 5882 dated to the fifteenth century) and the only one with the arms of Cardinal Capranica. As there is a frontispiece with the coat of arms of Dominicus Capranica at the beginning of the text and his shield is also featured on the binding, I think the manuscript might have been originally commissioned by a member of the Capranica family or by the Almo Collegio Capranica in Rome. Recognized as the oldest pontifical college in Rome, the Almo Collegio Capranica was founded by Cardinal Capranica in 1457 and had many notable ecclesiastics, including Pope Benedict XV and Pope Pius XII, among its students over the centuries. The coat of arms of Cardinal Capranica was adopted by the College and is still in use today.

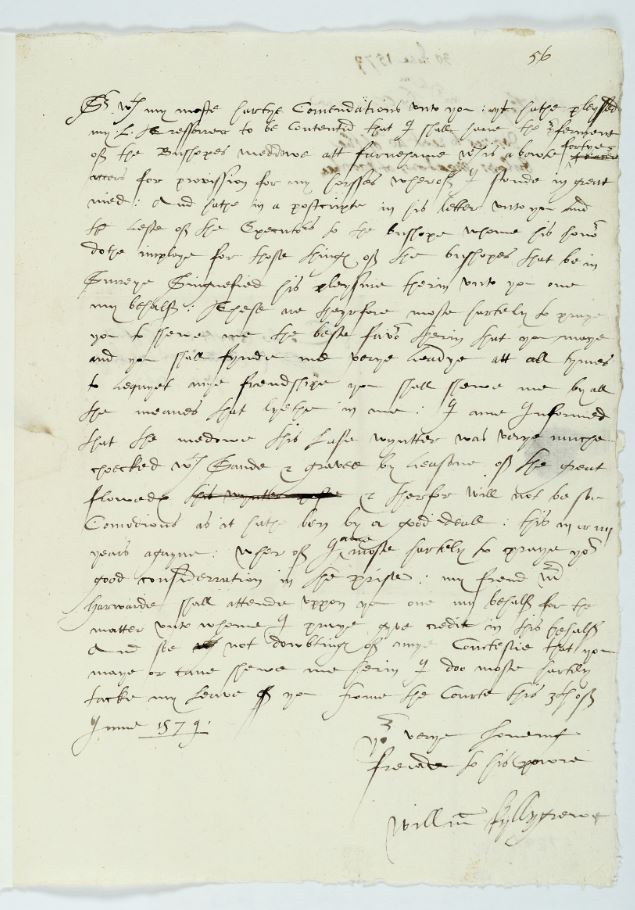

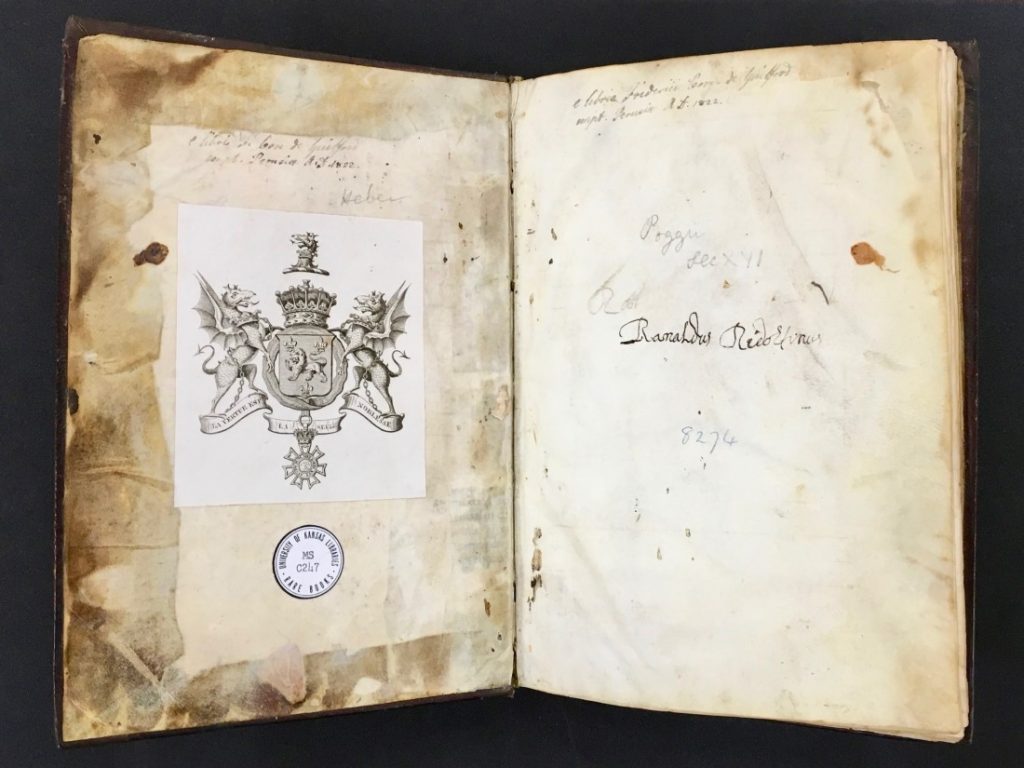

The exact origin of the manuscript is unknown but soon after its production, in the second half of the sixteenth century, it was probably in the possession of Rinaldo Ridolfini, a lawyer in Perugia, Italy, based on an inscription on folio 2r: “Ranaldus Ridolfinus.” Almost three centuries later, in 1822, the manuscript was purchased in Perugia by Frederick North (1766–1827), the 5th Earl of Guildford. Frederick North’s bookplate is pasted on the front pastedown (folio 1v) and two almost identical inscriptions, presumably by him, are found in the manuscript denoting the details of this purchase: “e libris F. Com. de Guilford empt. Perusia A. D. 1822” on folio 1v and “e libris Friderici Com. de Guilford empt. Perusia AD. 1822” on folio 2r.

The manuscript was later in the collection of Richard Heber (1773–1833), another renowned book collector in England, presumably acquired in the 1830 auction of Frederick North’s manuscripts. Within a few years, the manuscript was purchased by Payne & Foss for Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792–1872) in the 1836 auction of Heber’s manuscripts, and became part of the famous Phillipps manuscript collection, the largest private manuscript collection in the world at the time. It is inscribed “8274” in blue crayon on folio 2r, and there is also a rectangular Phillipps label with a typeset number “8274” adhered to the tail of the spine. It is estimated that Sir Thomas had some 40,000 printed books and 60,000 manuscripts in addition to paintings, prints, photographs and other materials. After his death, his will was contested but eventually Sir Thomas Phillipps’s library was inherited by Katharine Fenwick, his daughter, and later passed on to Thomas FitzRoy Fenwick, his grandson. This manuscript was probably among those inherited; however, there is no known record of it in the subsequent sales from the Phillipps library, which spanned several decades.

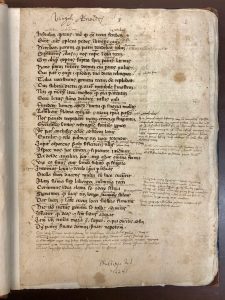

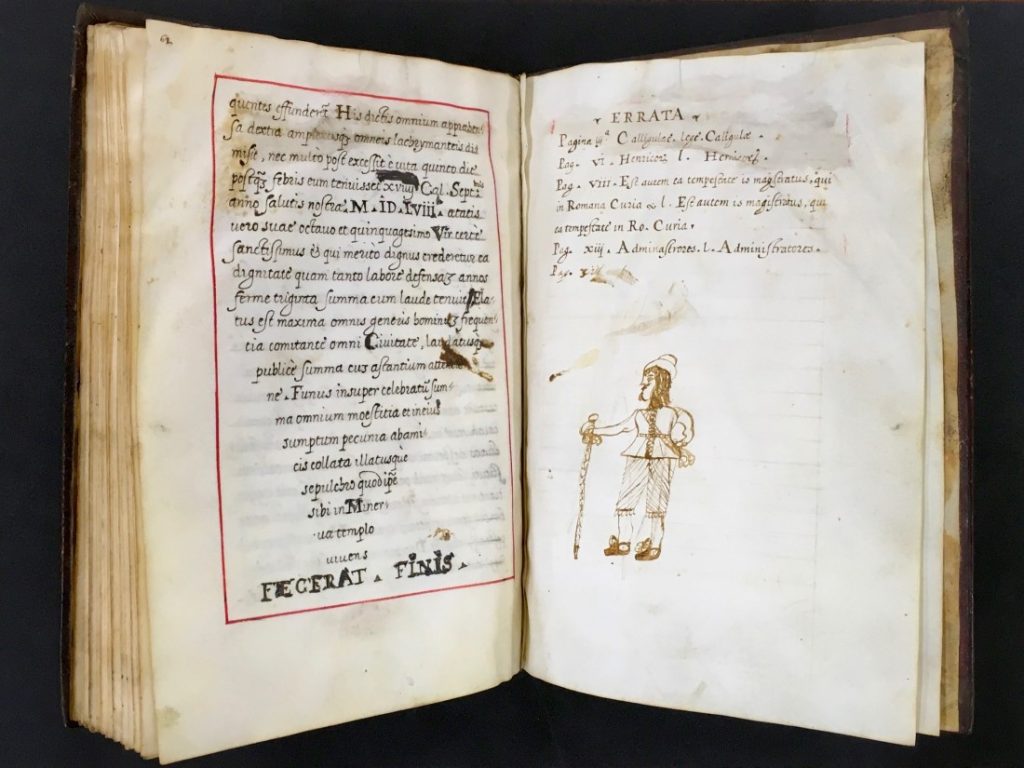

One of the most interesting features of the manuscript is that it contains an “Errata” at the end of the text on folio 36r in which the scribe lists the errors made and corrects the text. In medieval and early modern manuscripts, it is much more common to see mistakes corrected immediately over the text itself or in the margins. The end of the text on folio 35v, which is arranged like an inverted triangle, with the margins gradually increasing, as well as a doodle of a man with a sword on the lower half of folio 36r, probably drawn by a later owner, are also noteworthy.

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from Hofmann & Freeman Antiquarian Booksellers in March 1970, and it is available for consultation in the library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room.

Read more about Vita Capranicae and the other eight surviving manuscripts here: Ruut Kataisto. “G. B. Bracciolini: Vita Capranicae.” Studia Neophilologica 86, no. sup1 (2014): 104–11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00393274.2013.834105.

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher