Childhood Inspiration in Their Arts and Letters: Langston Hughes and Gordon Parks in Kansas

June 25th, 2024Spencer Research Library and the Gordon Parks Center have collaborated to create a pop-up display and small exhibition on the life, journey, and friendship of Gordon Parks and Langston Hughes.

The Gordon Parks Center in Fort Scott, with support from Humanities Kansas, curated an exhibition in 2023 exploring the connections between these two Kansas artistic luminaries and their local connections to the state.

This collaborative effort is inspired in part by a call by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) to highlight “African Americans and the Arts” in 2024. Working across collections and institutions, we have an opportunity to take a closer look at the varied histories and lives of African American artists.

Oftentimes, when we think of Black artistic movements, we often think of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s or the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. What is easy to overlook is the strong Kansas connection to both movements. Likewise, when we think of Kansas art and artists, it is easy to think of pastoral landscapes that capture the natural beauty of the prairie landscape and poetic descriptions of wildflowers and controlled burns. The linking of Kansas artists to these larger artistic movements that give rise to underrepresented voices in the world of arts and letters is not always so apparent. One of the most famous artists of the state is John Steuart Curry, the hand behind the Tragic Prelude mural painted in the rotunda of the capitol building in Topeka. But, did you know that another work by Curry, The Fugitive, was featured in an exhibition titled An Art Commentary on Lynching in 1935? Of the 38 artists whose work was included in the New York exhibition, Curry’s work was used on the cover of the exhibition catalog, designed to bring attention to the need for a nationwide anti-lynching law.

Two of the most recognized artists of the Harlem Renaissance and Black Arts Movement have roots in Kansas. This is no coincidence. Kansas in the early 20th century fostered a certain creative intelligence in these young men that would translate to and be understood by a large audience. Both Hughes and Parks grew up in working class families. Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, just across the state line from Baxter Springs, Kansas. Before his first birthday, he was living between Topeka and Lawrence. Locally, he attended Pinckney School and lived on Alabama Street in West Lawrence (now referred to as Old West Lawrence). He worked for a time as a newsie, selling the Saturday Evening Post and briefly the Appeal to Reason, a socialist newspaper published out of Girard, Kansas. He stopped delivering the Appeal after being told by the local editor of the former that the latter would get him into trouble. His introduction to the social issues discussed in the Appeal would shape a sense of solidarity with working class folks. Fifty miles away from Hughes’ birthplace is the childhood home of Gordon Parks, born in Fort Scott, Kansas, where his father was a tenant farmer. While Hughes was an only child, Parks was the youngest of fifteen.

Both Parks’ and Hughes’ earliest writings were inspired by memories of their Kansas childhoods and drew upon stories about people they knew. Hughes’ first novel, Not Without Laughter, is based on his upbringing in Lawrence. In his first autobiography, The Big Sea, he reflected on the ideas that would become Not Without Laughter. He wanted to write about a typical Black family in the Midwest and about people he had known in Kansas. Yet, he felt like his family and upbringing was not typical. “I gave myself aunts that I didn’t have, modeled after other children’s aunts whom I had known,” Hughes wrote. “But I put in a real cyclone that had blown my grandmother’s front porch away.”

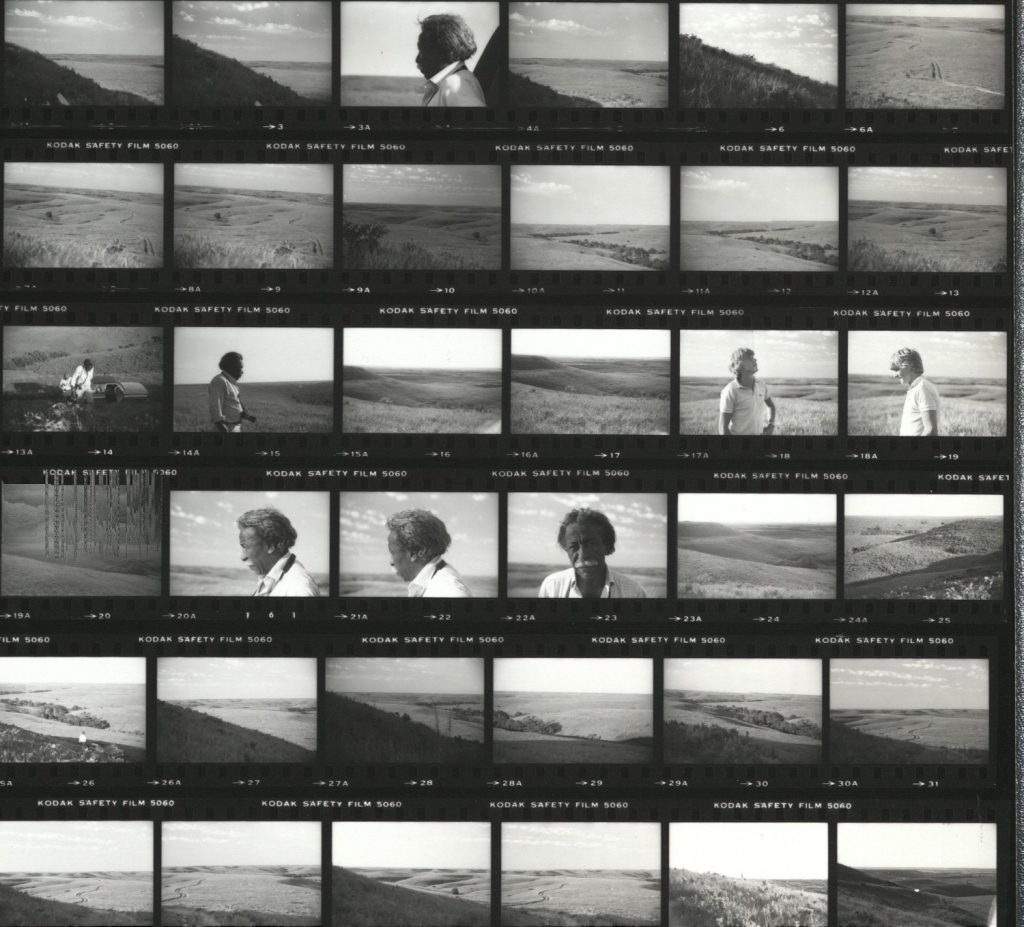

Parks drew on his own childhood while writing his first novel, The Learning Tree. Though set in the fictional town of Cherokee Flats with fictional characters, it closely resembled Fort Scott. When Parks later directed a film based on the story, he shot it on location in Fort Scott.

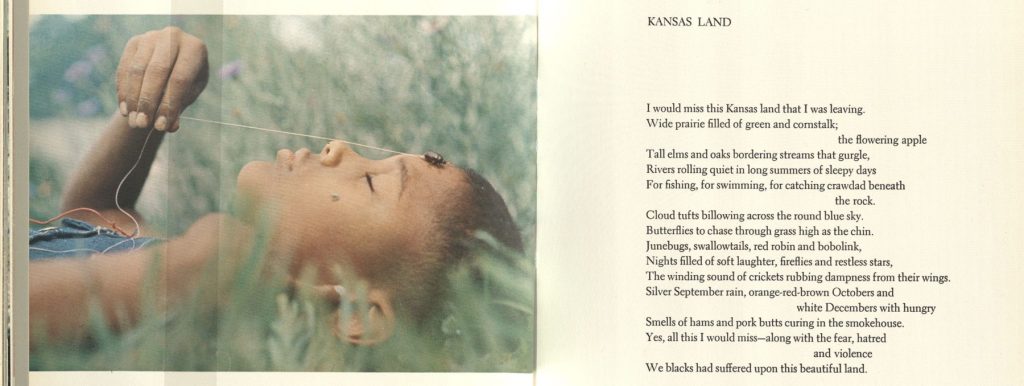

Kansas was not without racial bigotry. Both Hughes and Parks talked openly about being the subject of ridicule and name-calling and feeling fearful of violence. Despite the unpleasant realities faced during their childhoods, Kansas remained an important part of their lives. In Half Past Autumn, a retrospective of Parks’ work, he calls the state his touchstone:

“I looked back to the heaven and hell of Kansas and asked some questions…My memories gave me some straight talk. The important thing is not so much what you suffered or didn’t suffer, but how you put that learning to use.”

“There had been infinitely beautiful things to celebrate – golden twilights, dawns, rivers aglow in sunlight, moons climbing over Poppa’s barns, orange autumns, trees bending under storms and silent snow. But marring the beauty was the graveyard where, even in death, whites lay rigidly from Blacks. Twenty-odd years had passed when, with these things lying in my memory, I returned to Kansas and went by horseback to lock them firmly with my camera. Spring was wrapped around the prairies. Nothing much has changed – certainly not the graveyard.”

Langston Hughes returned to visit Lawrence after many years as well. Later in life, he was invited to speak at the University of Kansas, which he had visited as a small child. During one of his return visits, Hughes donated a collection of personal books and manuscripts to KU Libraries.

Throughout this summer, Spencer Library will feature a panel-display exhibit from the Gordon Parks Center accompanied with archival materials from the Kansas Collection to tell the stories of Langston Hughes and Gordon Parks and show the impact of their time growing up in Kansas on their life and careers. Their cultural expression through visual art, performing arts, literature, films, and music preserves our history, retells our stories for the next generation, and inspires our futures.

The exhibition will be on display through August 16, 2024, in the reception area of Spencer Research Library. The library and exhibit are free and open to everyone. You can visit our website to plan your visit.

Phil Cunningham

Kansas Collection Curator