Plants Between Leaves: The Long Lives of Preserved Plants in Library Shelves

July 2nd, 2024Every rare books library, at its heart, is a graveyard of forests long lost: paper has dominated the process of making books since the 15th century in Europe, and earlier in Asia and the Islamic world, so that almost every shelf holds the lives of hundreds, thousands of different trees and plants that were repurposed into a different sort of leaves entirely.

But in a handful of volumes on Spencer’s shelves, we might find something closer to nature than wood and flax linen pulped and lined into thin sheets for writing: we can find actual plants. These volumes preserve the past between their pages in a particularly literal sense, sometimes containing once plentiful plants that are now endangered, even extinct, serving as a testament to the lost flora of centuries past. These books were created not only by botanists but by farmers and shopkeepers as well, spanning the breadth of relationships that people have with nature: as scientists, their efforts to dissect, study, catalog, and document them so perfectly and completely; as farmers, their efforts to tame them and domesticate them; and as artists, to transform them into new forms of beauty and preserved life.

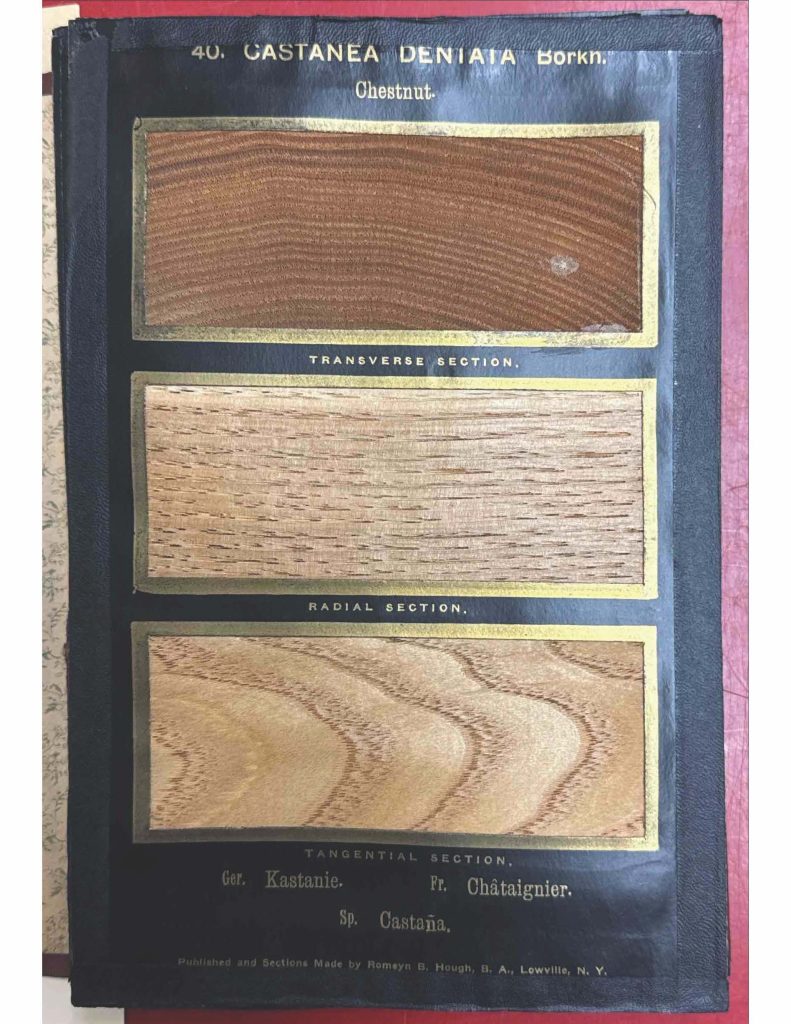

Cross sections of the American Chestnut, from Hough, Romeyn Beck. The American woods: Exhibited by actual specimens and with copious explanatory text. Lowville, N.Y.: Published and sections prepared by the author, 1888; Call Number: Pryce C11. The American Chestnut, once one of the most plentiful trees in the United States, was decimated by a fungal blight that killed 3-4 billion trees beginning in 1904, and now fewer than 10% of its original number survive.

Romeyn Beck Hough, author of The American Woods, took the idea of making a forest into a book quite literally: his work is not only a comprehensive representation of over 350 different species of trees that flourished across the late 19th- and early 20th-century American landscape, but a demonstration of a new technology of his own invention: he developed a cutter that could slice wood to 1/1200th of an inch, making slices of wood so thin they were translucent. The American Woods became a manifesto of wood samples: for each of the 350 species he included three different slices together with details of their botany, habit, medicinal and commercial uses. In total, the work consisted of 13 volumes, with a fourteenth published by his daughter using his notes after his death. Scientific illustration in Natural History already sought to recreate the details of living specimens in perfect detail and accuracy; through his wood samples in The American Woods, Hough took the next step in perfect replication.

Specimens of Meadow Barley, Meadow Cattail (now called timothy hay), and Marsh Bent from Swayne, George. Gramina pascua: or, A collection of specimens of the common pasture grasses, arranged in the order of their flowering, and accompanied with their Linnæan and English names, as likewise with familiar descriptions and remarks. Bristol: Printed for the author, by London.: S. Bonner, Castle-Green; and sold by W. Richardson, Royal-Exchange, 1790; Call Number: Pryce H1. Timothy hay is now a common grass for cattle and horses, as well as small, domesticated pets, thanks to its high fiber content.

The Gramina Pascua, or A collection of specimens of the common pasture grasses, arranged in the order of their flowering was published in 1790 by Reverend George Swayne, a farmer, rather than a scientist. Swayne was a learned man, with two degrees from Oxford. In addition to serving as a vicar in Gloucester, England, he was active in the agricultural societies of the early 19th century, clubs that consisted of farmers and scientists dedicated to discussing practical and theoretical farming. Gramina Pascua had a more practical purpose to its scientific exploration of botany, however, as it was borne from a broader interest in the early 19th century in cultivating grasses in the meadowlands and pastures of Britain for grazing animals and harvesting for food. Between 1700 and 1850, agricultural output quintupled thanks to technological advances and studies that sought to understand and optimize farming, as was the case for Reverend Swayne and his Gramina Pascua.

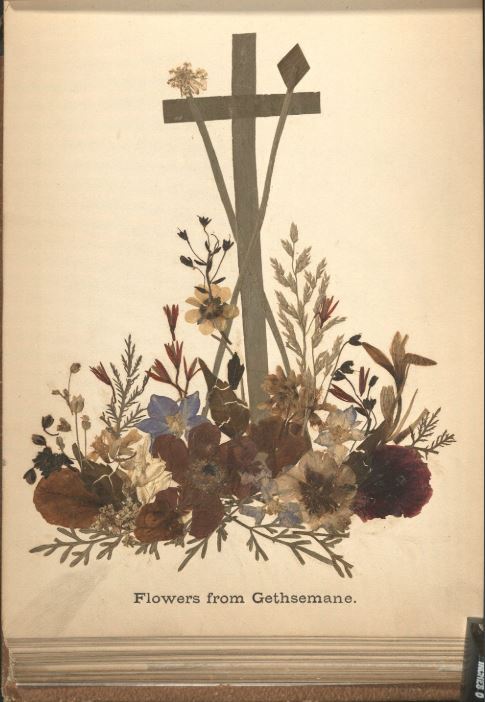

Pressed Flowers from Gethsemane, from Meo, Boulos. Flowers from the Holy land. Carefully arranged. Jerusalem: Printed and bound by Joseph Schor, 1888; Call Number: Pryce AK1. Gethsemane was a garden of olive trees across the Kidron Valley, where Jesus was said to have prayed before his arrest and crucifixion.

Boulos Meo was neither scientist nor farmer – no, he was a shopkeep in Jerusalem, at Jaffa Gate, one of the seven main gates of the Old City walls. Technically, neither was Boulos Meo an artist – he was merely the publisher and seller of Flowers from the Holy Land, whose artist remains unknown, whether it was Boulos himself or perhaps someone he knew. Boulos Meo sold, at first, rugs, beginning in 1872, but eventually expanded to sell antiques, religious icons, jewelry, and souvenirs to tourists and pilgrims from around the world visiting the city. Christian pilgrims had brought tangible items back from their journeys for centuries – stones were among the most popular souvenirs from Jerusalem, with one stone from each holy site in the Stations of the Cross, a processional route across fourteen sites in Jerusalem, but fragments of flowers and plants were also common. Flowers from the Holy Land took that practice and transformed it into an artbook tied closely to the place of its making, where the descriptions of the flower arrangements included not the names of the flowers, but the names of the holy sites where they were gathered, to connect the physicality of the book – the flowers themselves, and not merely their visual nature – intrinsically with places of religious meaning. As a result, the book became an embodiment of the places named in the text, its flowers an echo of its pilgrim owner’s memories of the places they visited.

One beauty of these books is that no two are perfectly alike, for each slice of wood, every pressed flower is distinct from its brethren in another copy, even when the texts are identical. Some two hundred copies of The American Woods survive in libraries, but like fingerprints, their thin slivers of wood cannot perfectly match one another. A little more than ten copies of Gramina Pascua are held on library shelves, and twelve of Boulos Meo’s pressed flower books still survive in public collections, though perhaps more are tucked away on the shelves of descendants of the pilgrims who visited Palestine at the turn of the century, their flowers still delicately pressed between the pages.

On July 24th, and throughout the coming Fall and Spring semesters, the KU Libraries will be hosting a range of events focused on plants, botany, and gardening, including a Plant Swap event on July 24th, which will feature several books from Spencer making a voyage of their own from their shelves to 3 West in Watson to be featured side by side with their living, breathing plant counterparts. Visitors will be able to pick up a potted lavender plant and then browse a 1640 illustrated herbal to see how lavender has been a part of human life and study for over 400 years. And perhaps, if you are so inclined, you might pick a few leaves of your own plants, and press them between the pages of a book at home, for future generations to see how plants still interleaf with knowledge and learning today.

Eve Wolynes

Special Collections Curator

Citations:

Brett, Jim. “Gramina Pascua,” in Collection Update, no. 15. Edited by Carol Goodger-Hill. Guelph, Canada: University of Guelph Library, 1992.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Gethsemane.” Encyclopedia Britannica, June 14, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/place/Gethsemane.

Limor, Ora. “Earth, stone, water, and oil: Objects of veneration in Holy Land travel narratives,” in Natural Materials of the Holy Land and the Visual Translation of Place, 500-1500. Ed. By Renana Bartal, Neta Bodner, and Bianca Kühnel. Routledge: 2017. Pp. 3-18.

Pizga, Jessica. “Hough’s American Woods.” The New York Public Library, March 12, 2012. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2012/03/12/houghs-american-woods.

Sharar, Adam Abu. “The Shop and Bab al-Khalil,” in Jerusalem Quarterly File, no. 15, Winter 2002. pp. 32-38.

Van Drunen, Stephen G.; Schutten, Kerry; Bowen, Christine; Boland, Greg J.; Husband, Brian C. (September 2017). “Population dynamics and the influence of blight on American chestnut at its northern range limit: Lessons for conservation”. Forest Ecology and Management. 400: 375–383.