Spencer’s March-April Exhibit: “From Shop to Shelf”

March 5th, 2024Conservators often say that what draws them to this work is the variety – every day is different! Always something new to learn! Never a dull moment! In my role as special collections conservator at KU Libraries, I am fortunate to work on interesting items from all of the collecting areas within the Kenneth Spencer Research Library, and my day-to-day experience bears out the truth of those clichés. Each book, document, and object I work with wears evidence of its own unique history. Physical condition, materials, marks or repairs made by persons past – sometimes these features tell a clear story about the life an object has lived, and sometimes the picture is murky, fragmented, or confusing. In the new short-term exhibit on view in Spencer Library’s North Gallery, I returned to the subject of a 2016 blog post to explore the ways that a book’s binding might provide information about who owned the book and how it was used.

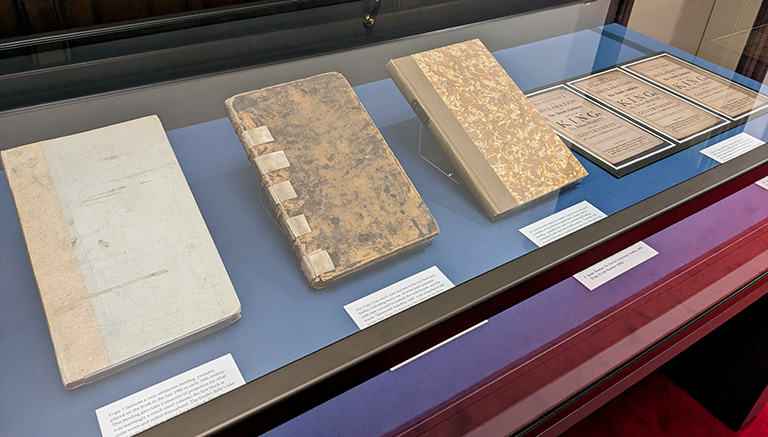

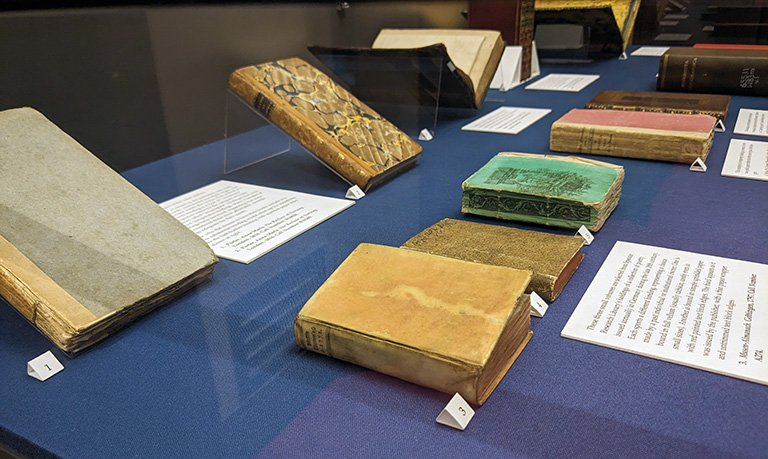

Spencer Library’s three copies of Thomas Sprat’s A true account and declaration of the horrid conspiracy against the late king, His present Majesty, and the government: as it was order’d to be published by His late Majesty are displayed in the first exhibit case. This book relates Sprat’s official account, as Bishop of Rochester, of the failed 1683 Rye House Plot to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother (and successor) James, Duke of York. The horrid conspiracy, as we’ll call it, was printed in London in 1685 by Thomas Newcombe, “One of His Majesties printers; and … sold by Sam. Lowndes over against Exeter-Change in the Strand.”

After leaving Lowndes’ shop these three edition-mates embarked on separate journeys, only to arrive back together again in our stacks over three hundred years later. The books’ differing conditions and binding styles invite speculation about their adventures (and misadventures!) in the intervening years. The exhibit compares the physical characteristics and evidence of use seen on the three volumes and considers what these features might tell us about who owned them and how they were used. We cannot know for sure, but it is so fun to wonder!

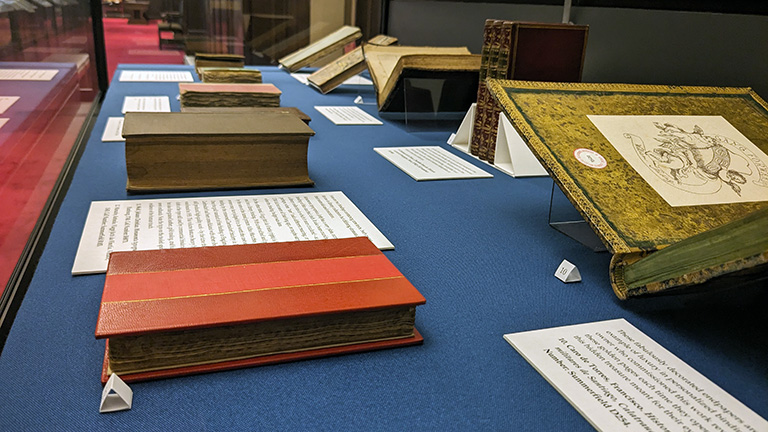

In case two, we expand our examination of different binding styles to include a small selection of bindings from Spencer Library’s rare books collections. The display includes books in original paper bindings or wrappers from the publisher, books custom-bound for private owners in either a plain or a fine style, and others bound simply and sturdily for use in a lending library. Spencer Library’s collections are rich with examples of bookbinding styles across the centuries; this assortment of volumes represents just a fraction of the many ways that a book might have been bound either by bookseller, buyer, or library.