Working at Spencer for the past two years, I’ve discovered many amazing manuscripts and old novels that I never dreamed of getting the chance to actually work with. An even more far-fetched idea, however, was finding books that I read when I was a kid and had completely forgotten about.

Yet I did.

It started off as any other day: reshelving books within the stacks. I pushed my book cart, complete with its squeaky wheels, down the rows as I returned the books back to their homes on the shelves. Walking around the perimeter of the stacks, I found a section of books that I hadn’t noticed before. They stood out amongst the old, leather bound covers of books published before the 1700s. Instead, these spines were cloth and colorful, rich in design and detail.

And they looked eerily familiar.

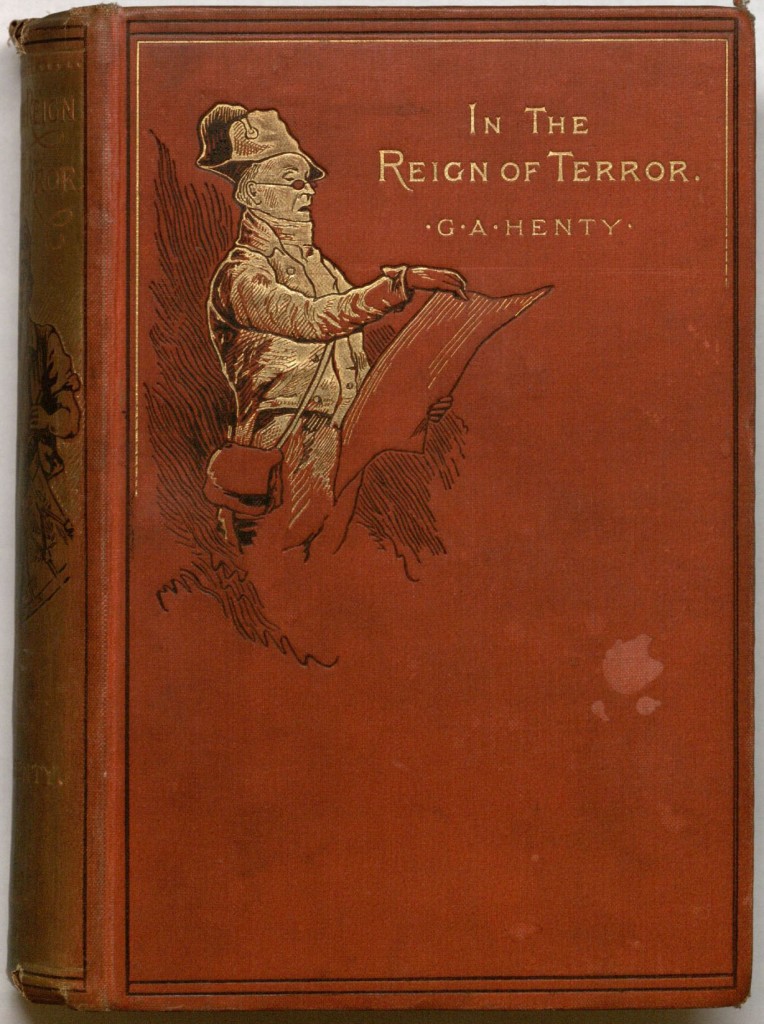

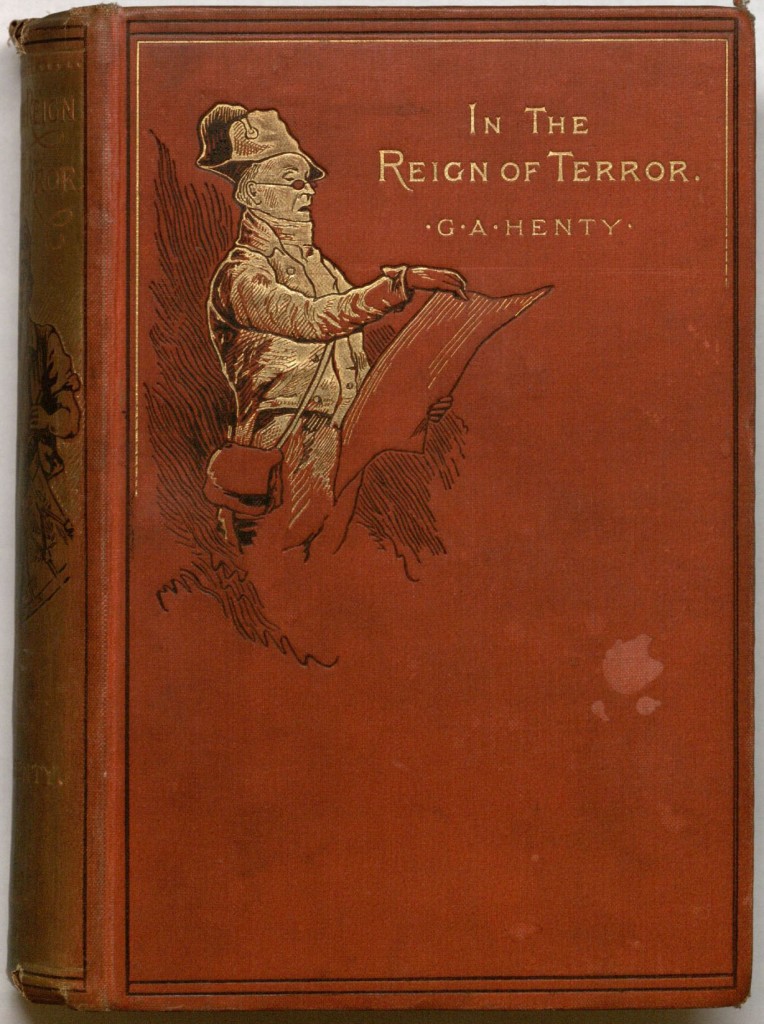

The cover of In the Reign of Terror by G. A. Henty.

Illustrated by J. Schönberb. London: Blackie, 1888.

Call Number: O’Hegarty B805. Click image to enlarge.

Leaving my book cart behind me, I walked up to take a closer look, disbelief forming in the back of my mind. No, these couldn’t be the same books I read in middle school, I thought. There was no chance. Upon closer inspection, my gut was proven to be right: I had discovered a treasure trove of books by British author George Alfred (G. A.) Henty. Shelves upon shelves were lined by his masterpieces, a series of adventure books that I’d barely scratched the surface of, reading them in my youth.

Instantly, I was transported back home, as an eleven-year-old, acne-riddled, glasses wearing middle-schooler, standing in my public library. I discovered a book by accident: it had a simple red cover that was torn on the sides. The title read In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy by G. A. Henty. I have never heard of him before, but I decided to take the book home with me and give it a try.

I finished it within the week.

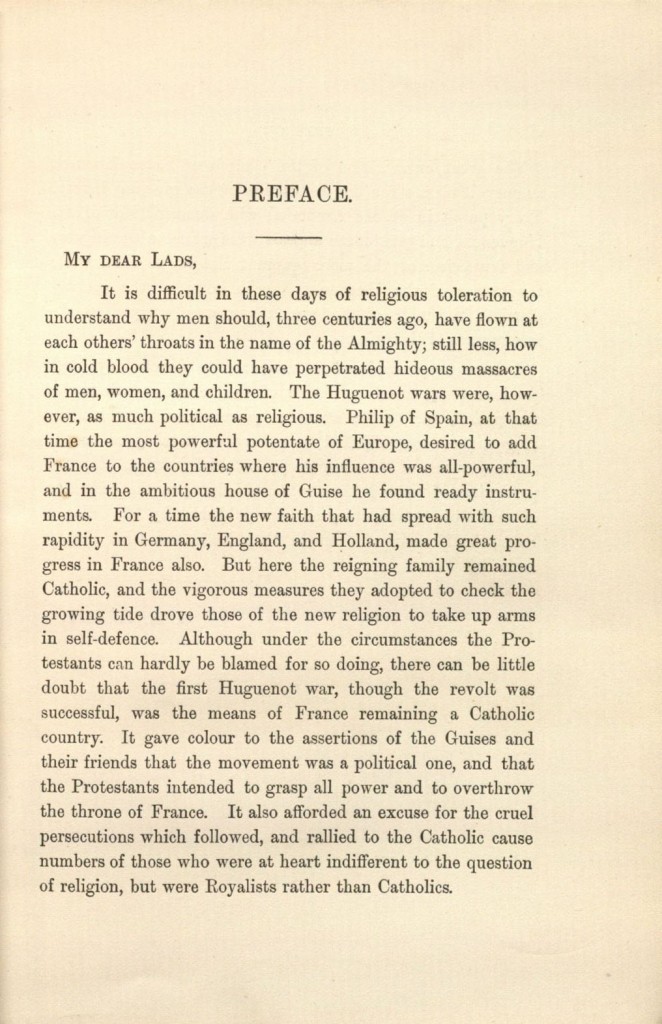

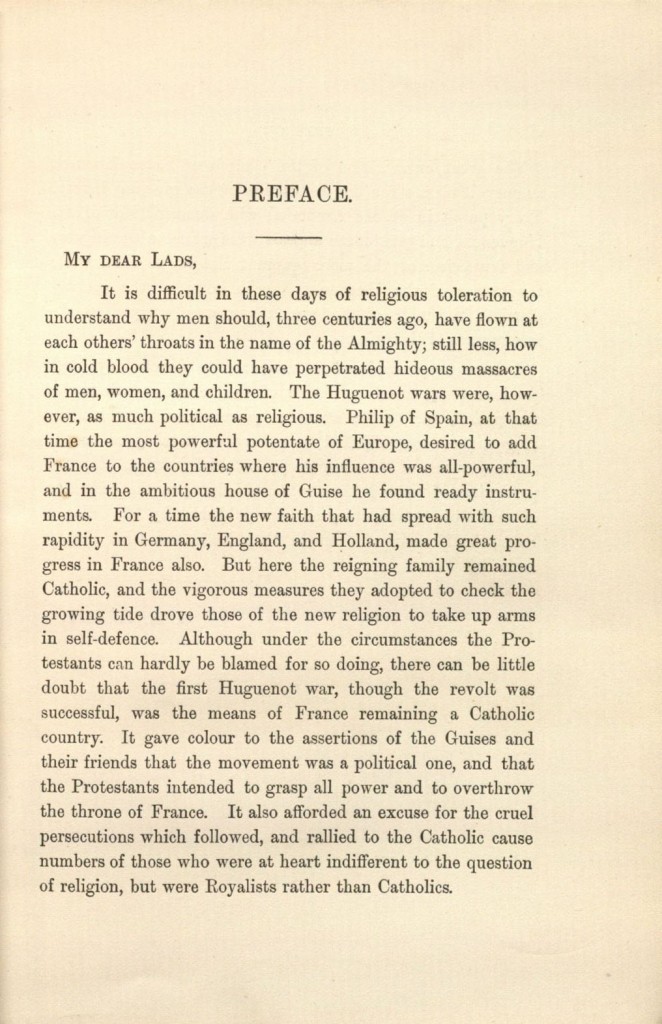

Henty was a mastermind of writing stories threaded within historical events. In the Reign of Terror was about a boy named Harry Sandwith, who was sent to live with the Marquis de St. Caux during the French Revolution, in a time when political stresses tore the country apart during the reign of King Louis XVI. Even though his novels were written in the late nineteenth century and intended for a young male audience (he always started off his tales with a letter to his audience, addressed to his “Dear Lads…”), I still found them to be enlightening, enjoyable and one heck of a political and historical ride.

And I had completely forgotten about Henty and his tales.

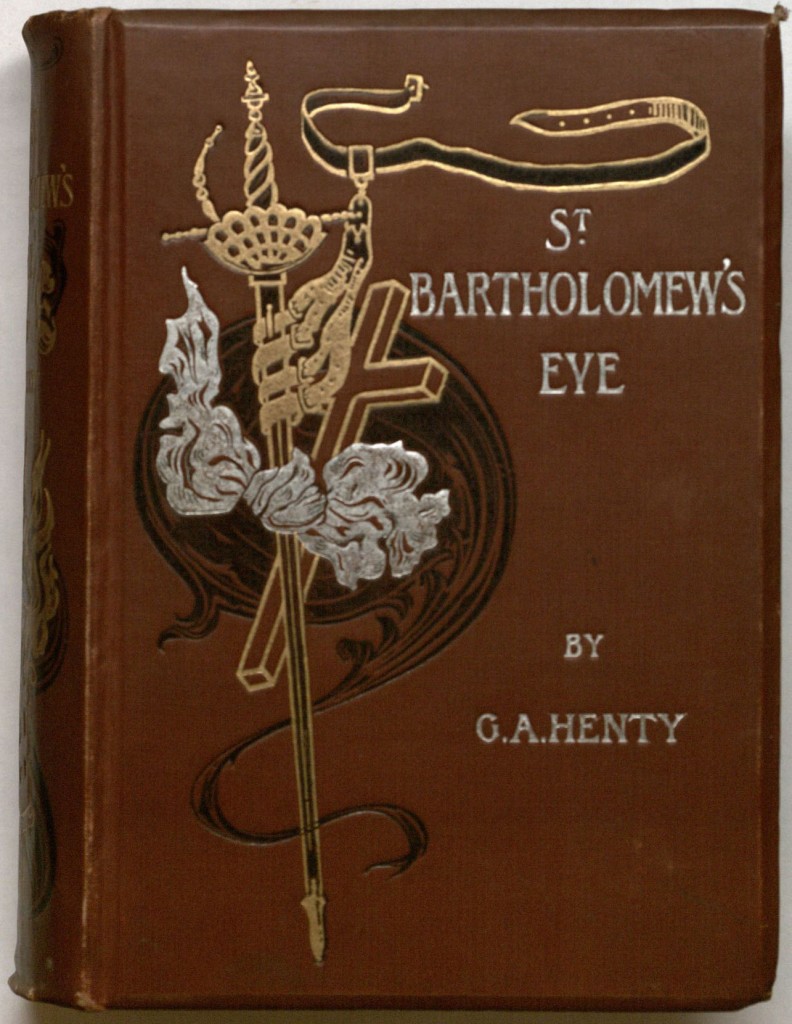

The cover of St. Bartholomew’s Eve by G. A. Henty.

Illustrated by H. J. Draper. London: Blackie, 1894.

Call Number: O’Hegarty B818. Click image to enlarge.

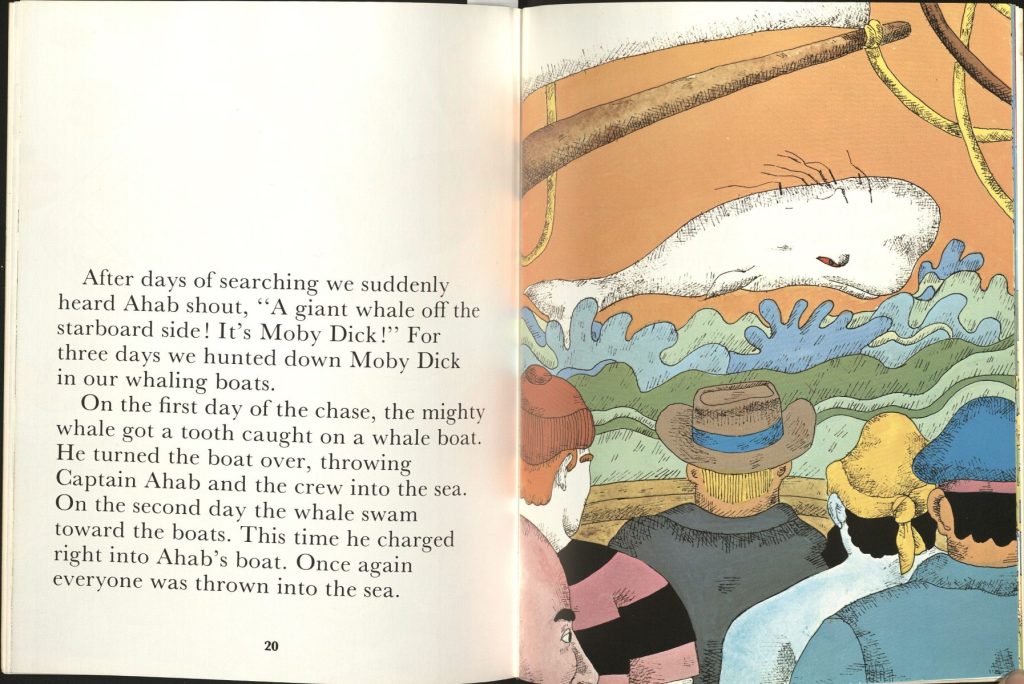

Since being reunited, I have been reminded of the books that I raided when I was a kid. After reading Reign, I quickly went through our library’s collection back home, which consisted of six titles. My favorite I’ve read is St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, which is a tale of the Huguenot Wars.

An illustration in St. Bartholomew’s Eve by G. A. Henty.

Illustrated by H. J. Draper. London: Blackie, 1894.

Call Number: O’Hegarty B818. Click image to enlarge.

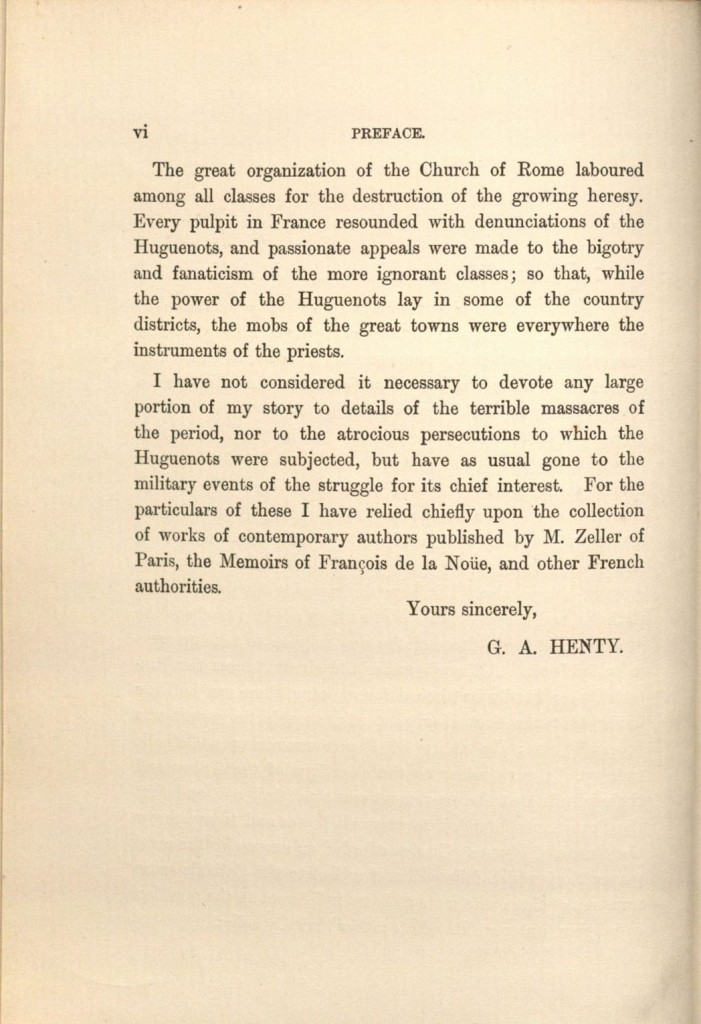

The preface of St. Bartholomew’s Eve by G. A. Henty, addressed to “my dead lads.” Illustrated by H. J. Draper.

London: Blackie, 1894. Call Number: O’Hegarty B818. Click image to enlarge.

Now that I have rediscovered Henty, I’ve been looking into him again and trying to decide which book to read next in order to get back into reading him. Yet I also realized that there are plenty of controversies surrounding the author I’d accidentally discovered. While these stories are advertised as stories of adventures for young boys, they were also criticized – both during the time of publication and especially since then – as being xenophobic towards anything that wasn’t part of British culture and nationalism. His books were also labeled as strong propaganda towards British imperialism, raising the question of if there was another purpose behind Henty’s agenda for writing these novels.

None of this political scandal was noticed by me as a young reader, but recognizing it now, I think it would be interesting to go back and reread some of his stories, or pick up a brand new one. Rediscovering one of my favorite childhood authors was something I definitely didn’t expect to happen while working within the stacks. It was an experience that made me feel like I went back in time, while at the same time, opened a door to learning more about this controversial, yet very popular, late-nineteenth-century author.

It just goes to show that no matter what you’re doing in a library – working, researching or just simply browsing – the treasures waiting to be discovered are endless.

Nicole Evans

Public Services Student Assistant

![Image of Rossetti to Swinburne [circa Nov. 1871p.1]](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/MS23D3.2_Rossetti_Page_1-150x150.jpg)