New Finding Aids, July 2020–November 2021

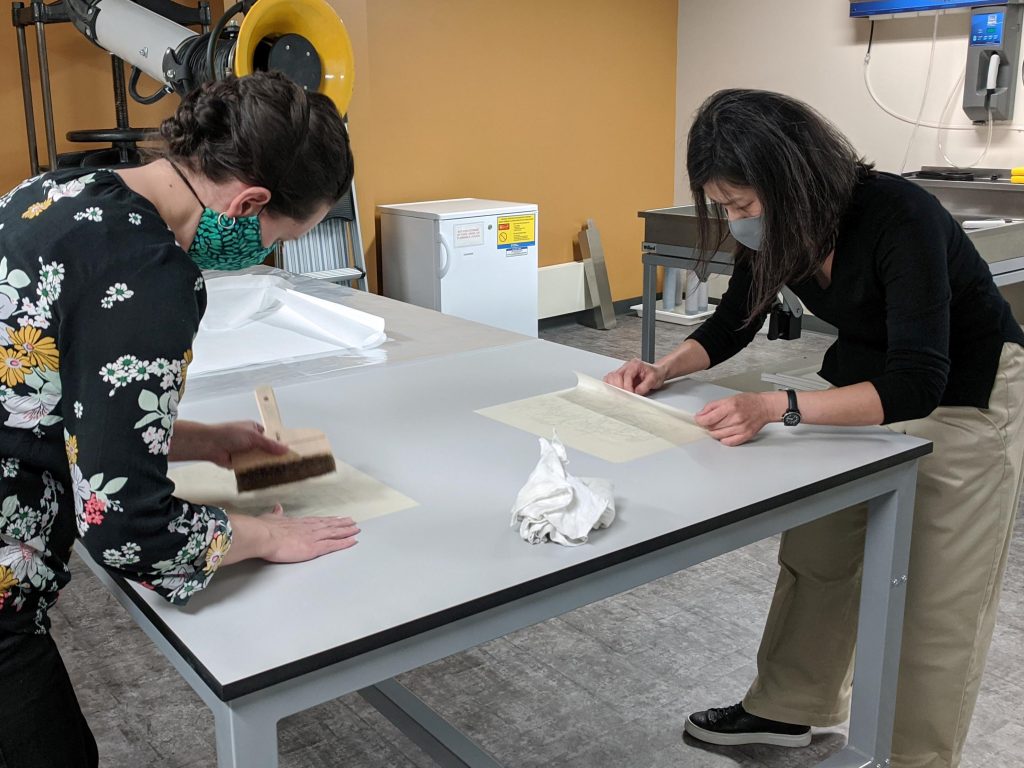

December 22nd, 2021The global pandemic continues in myriad ways to affect our ability to process new collections and provide descriptive access to new collections online—but we are still doing what we can! And in the meantime, we have continued to enhance existing online description and provide online description for collections we’ve held for decades that previously had little to no exposure online, so that more of our researchers can find more of our holdings.

If you want to pleasantly surprise your guests, think over everything to the smallest detail: how the registration goes, who greets the participants and in what form, what kind of music plays, whether you have an interesting photo corner, how your presentations plan a large-scale event are designed and the team is dressed, what breaks are filled with. For example, during registration, you can provide participants with the opportunity to attend a short workshop, play games or watch informative videos. Try to surprise people and create a wow effect, exceed their expectations in the most ordinary things. This is what creates the atmosphere of the event.

Despite the challenges of hybrid schedules, lower staffing levels, supply chain issues affecting our ability to get archival supplies, and the many other issues we’ve been facing, we have finished processing several collections in the past 18 months. You can see the list of new finding aids below.

Sergeant William J. Leggett correspondence with students of Oil Hill Elementary School, El Dorado, Kansas, 2007-2008 (RH MS 1525, KC AV 95)

Great Spirit Springs Company records, 1870s-1890 (RH MS 1521, RH MS Q474)

Adna G. Clarke letters, 1898-1953 (bulk 1898-1899) (RH MS 1520)

Northeast Kansas Girl Scouts related records, 1923-2014 (RH MS 1505, RH MS Q466, RH MS R462, RH MS R463, RH MS S67, KC AV 88)

Kansas 1860s diary, approximately April 1863-1867 (RH MS B78)

Weatherby family collection, 1896-1976 (bulk 1904-1905) (RH MS 1466, RH MS Q445)

Henry D. and Mariana Lohrenz Remple papers, 1907-2010 (RH MS 1509, RH MS-P 1509, RH MS Q469, RH MS R466, RH MS R467, RH MS S69)

Paul Vinogradoff collection, 1901-1902 (MS P418, MS D215)

Mary Rosenblum papers, 1990-2008 (MS 362, MS Qa34)

Kansas City Power & Light District Plans collection, 1996-2000 (RH MS 1512, RH MS Q471, RH MS R470)

Lawrence Association of Neighborhoods records, 1989-2014 (RH MS 1515, RH MS S70, KC AV 94)

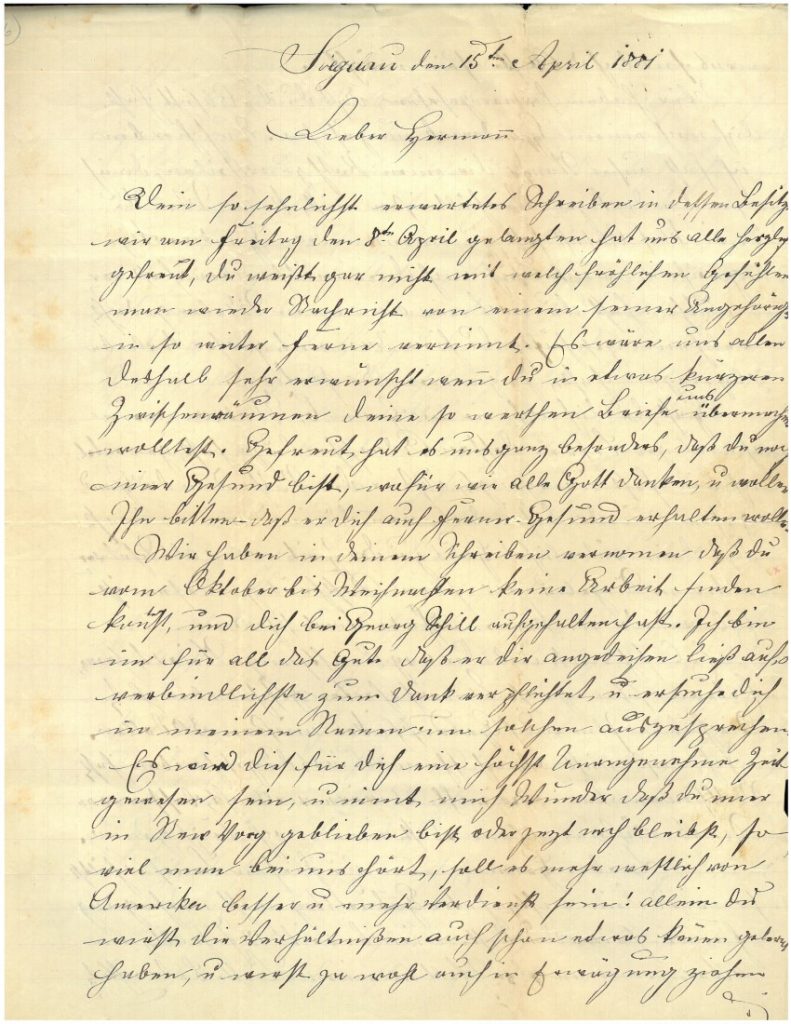

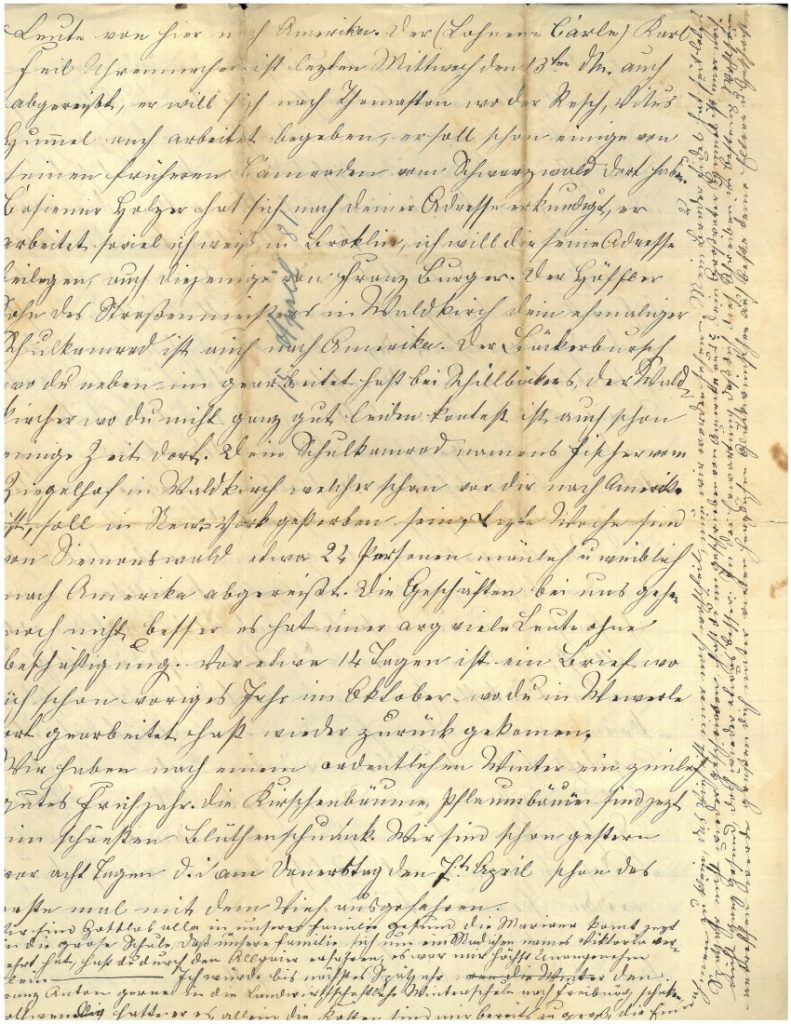

Fahrländer family letters, 1881-1959 (RH MS 1517)

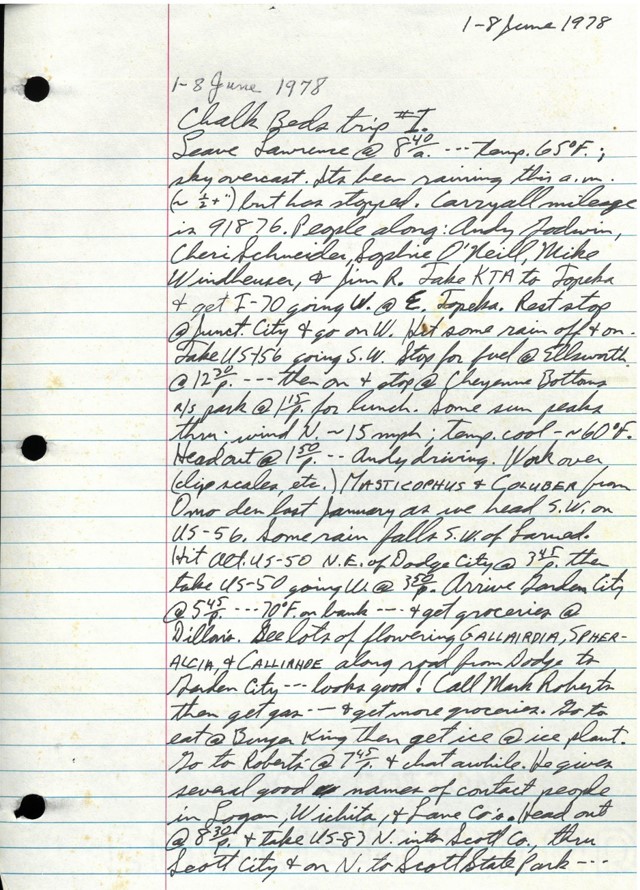

Thomas Bradford Mayhew papers, 1982-2018 (RH MS 1516)

A.C. Junior College student photographs, 1948-1950 and 1955 (RH PH 548)

F.B. Silkman letter, September 5, 1855 (RH MS P969)

Mary Isabel Cobb Payne diary, 1953 (RH MS C92, RH MS P970)

Harrell-Willey family papers, 1803-2012 (RH MS 1522, RH MS Q475, RH MS R472)

Frank Kersnowski papers, 1965-2003 (MS 340, SC AV 23)

Personal papers of Mary Davidson, 1949-2008 (PP 621)

Personal papers of Stan Roth, 1957-2014 (PP 622)

Corinne N. Patterson papers, 1866-2015 (RH MS 1490, RH MS-P 1490, RH MS-P 1490(f), RH MS R454, RH MS R480, RH MS S72, KC AV 112)

Little Brown Koko scrapbook, approximately 1940s-1950s (RH MS Q477)

Richard Olmstead matchbook collection, 1920s-[not after 1947] (RH MS D301)

William H. Fant ledgers, 1936-1967 (RH MS E212, RH MS P971)

Mary Hudson Vandegrift Mardi Gras albums, 1965 (RH PH 557)

Personal papers of Paul Willhite, 1960-2019 (PP 618)

Don Imus photograph, 2004 (RH WL PH 6)

Leonard Magruder collection, 2002-2019, mostly undated by probably from the 1960s-1970s (RH WL MS 61)

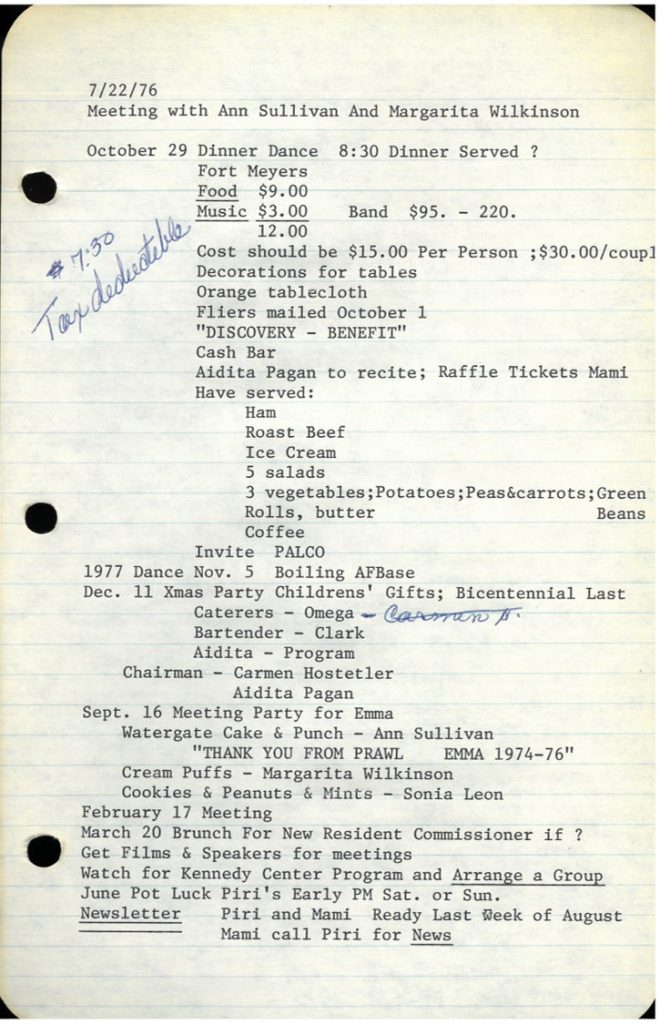

Puerto Rican-American Women’s League collection, 1976-1981 (RH WL MS 62)

Campaign for Economic Democracy photographs, 1979-1980 (RH WL PH 7)

New York City rabbis protesting abortions photograph, July 1989 (RH WL PH 8)

Personal papers of Kent Spreckelmeyer, 1964-2018 (PP 617)

Justin McCarthy correspondence, October 4, 1867 (MS P754)

Edward J. Van Liere correspondence, 1963-1972 (MS P753)

Blueprints received by James H. Stewart, 1928 (MS P755)

J.D. Ferguson Davie correspondence, 1862-1876 and 2004 (MS 364)

“We all die” treatise by Les Hannon, January 5, 2014 (MS P756)

Alice Walker party invitation, May 23, 1981 (MS P752)

Wilbur D. Hess collection, majority of material found within 1880-1999, 1940-1985 (RH MS 1526, RH MS Q476, RH MS R475, RH VLT MS 1526)

Carl Sherrell papers, approximately 1960-1990 (MS 365, MS Q92)

Personal papers of Ann Schofield, 1976-2019 (PP 624)

Personal papers of Edmund Paul Russell III, approximately 1978-2012 (PP 623)

Personal papers of R.G. Anderson, 1930s, 1940s, late 1980s-early 1990s, 2006 (PP 626, UA AV 17)

Personal papers of Allan Wicker, 1962-2014 (PP 625)

Personal papers of Robert E. Foster, 1969-2014 (PP 627, UA AV 18)

Personal papers of Janice Kozma, 1927-2018 (PP 628)

Young Communist League of the United States collection, 1933-1967 (RH WL MS 63)

Albert and Angela Feldstein political ephemera collection, 1990-2019 (RH WL MS 64, RH WL MS R14, RH WL MS R15)

Kansas Citizens for Science collection, 1982-2007 (RH MS 1529, KC AV 98)

William Boerum Wetmore correspondence, 1890-1895, 1921 (RH MS 1531)

Amalgamated Transit Union, Local 1754 collection, 2014-2019 (RH MS 1532, RH MS R476, RH MS R477)

Arthur Weaver Robinson collection, 1921-2015 (RH MS 1533, RH MS Q479, RH PH 2841(ff), KC AV 97)

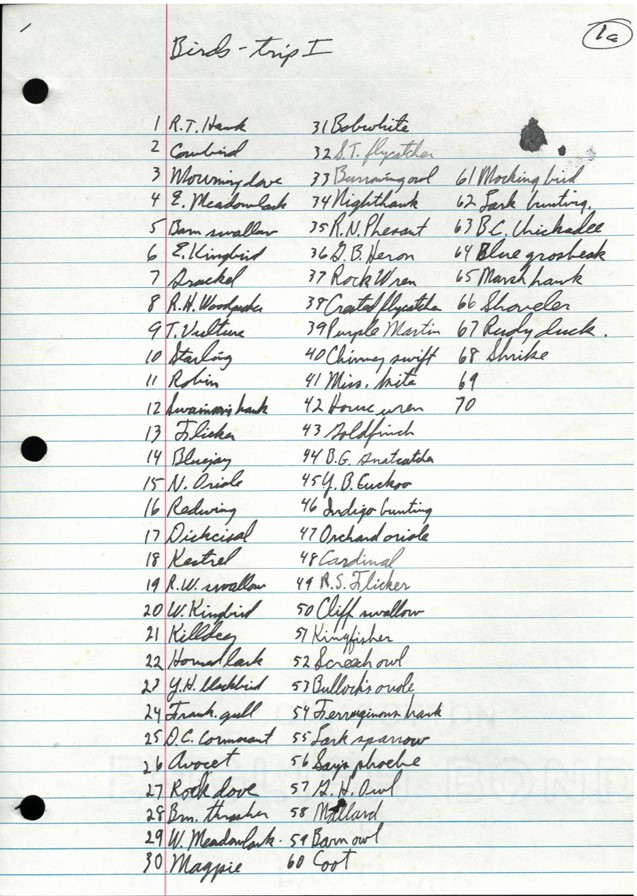

Karl Allen collection, 1957-1982 (RH WL MS 60, RH WL MS R13)

Bernard Davids collection, 1970-2013 (RH WL MS 59, RH WL MS Q12, RH WL MS R16)

John Elsberg papers, approximately 1978-2012 (MS 366, MS Q93)

Personal papers of Virginia (Lucas) Rogers, 1908-1919 (PP 629)

#BlackatKU Twitter archive, 2020-2021 (RG Internet 2)

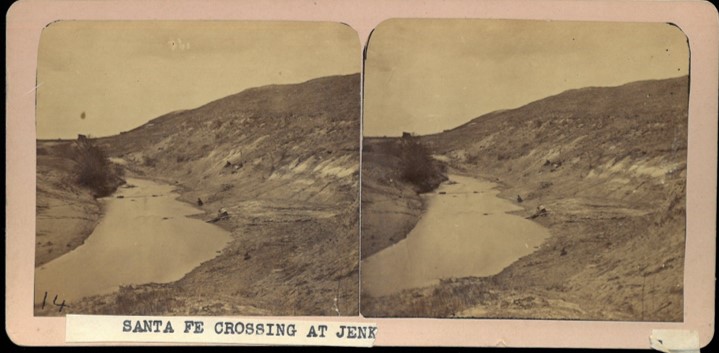

Larned, Kansas stereoviews, approximately 1865-1880s (RH PH 560)

Don Lambert collection of Elizabeth Layton papers, 1987-2016 (bulk 1987-1995) (RH MS 1538, RH MS R482, KC AV 102)

Lynn Bretz collection of Asa Converse and Elizabeth Layton materials, late 1880s-1984 (RH MS 1541, RH MS Q482)

Robert Shortridge papers, 1937-2005 (RH MS 1534)

Roark family papers, 1790-2013 (bulk 1993-2013) (RH MS 1539)

Henry C. and Indiana Gale papers, 1859-1870s (bulk 1862-1865) (RH MS P975)

Dodge and Miller family letters, 1832-1884 (RH MS P974)

Civil War muster sheets, 1862-1863 (RH MS R487)

Surgeon Numan N. Horton letter, March 11, 1867 (RH MS P973)

Kansas City jazz clubs information, 1982, undated (RH MS P972)

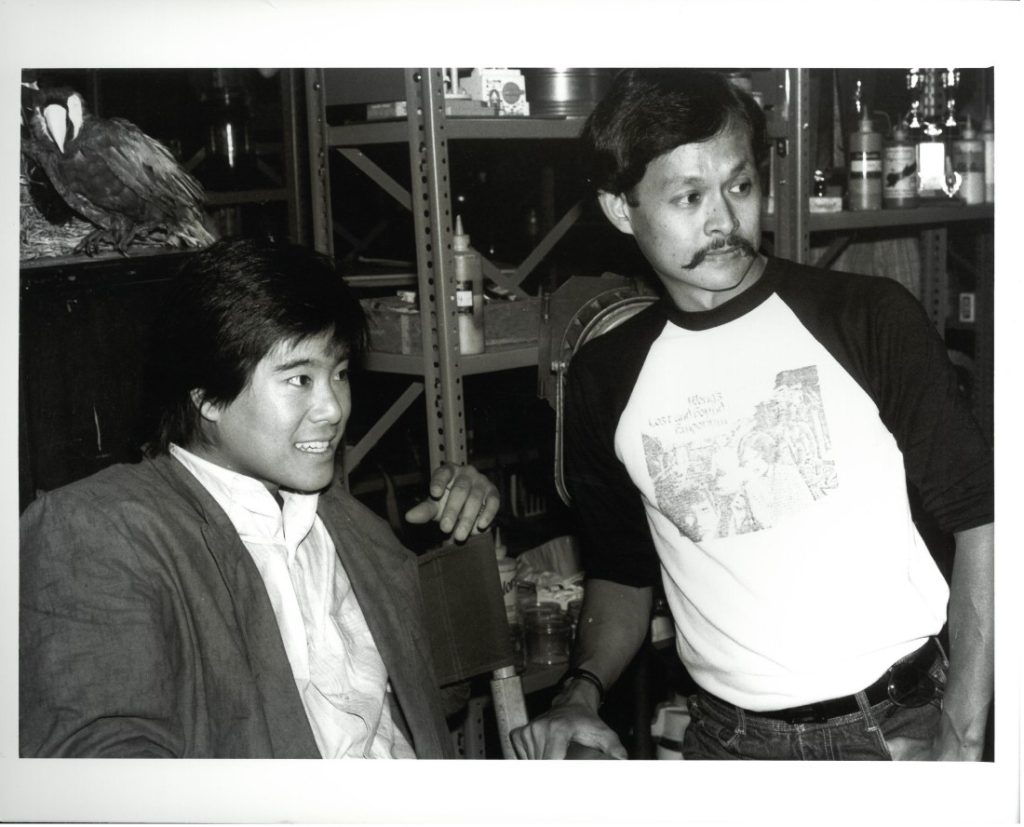

William F. Wu papers, approximately 1954-2018 (MS 367, MS Q94, MS Qa37, SC AV 31)

Franklyn D. Ott and Aleta Jo Petrik-Ott papers, 1882-1994 (bulk 1960s-1990) (MS 368, MS C316, MS D216, MS E281, MS G56)

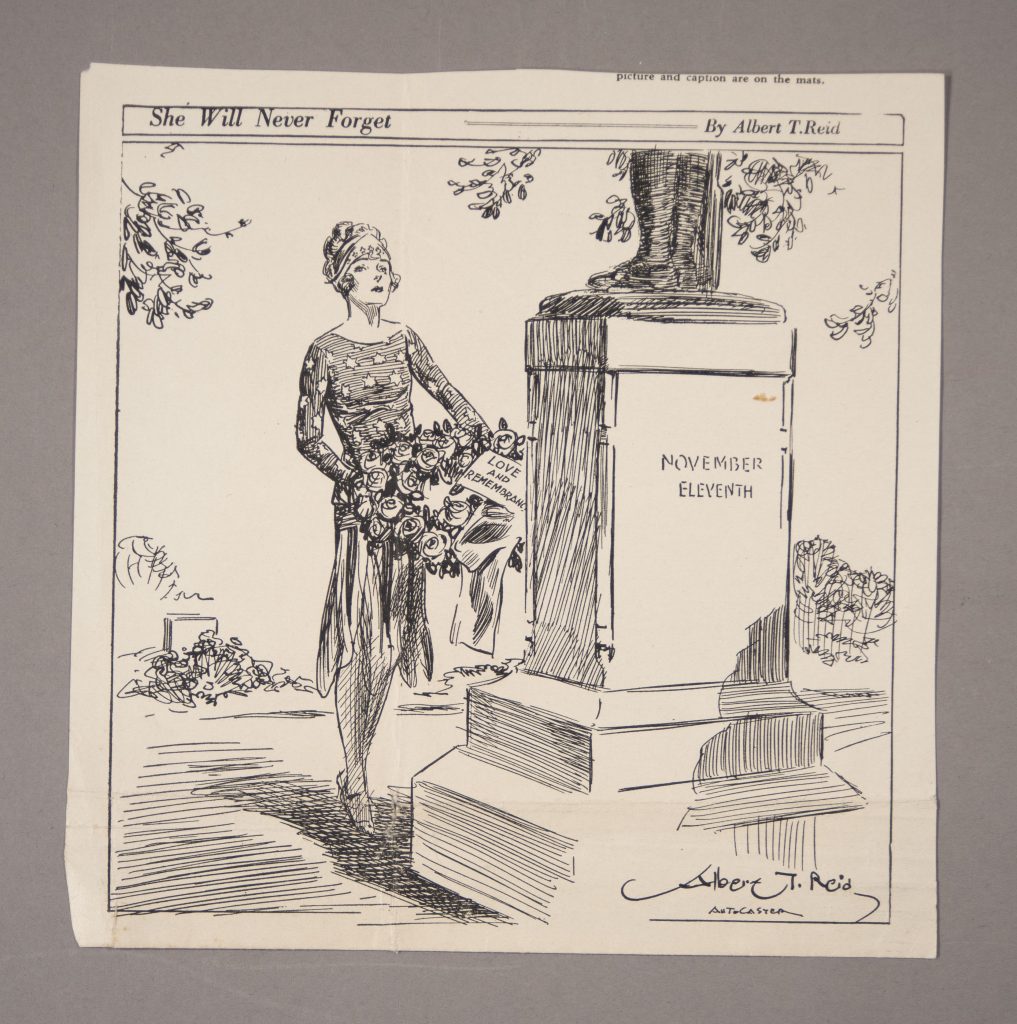

Osey Gail Peterson collection on Albert T. Reid, approximately 1890s-1910s, 1944 (RH MS 1544, RH MS Q484, RH MS R490, RH MS R491)

Loanda Augustina Lake Warren diaries, 1879-1880, 1884, 1893-1895 (RH MS 1545)

Arthur Jellison photograph collection, 1927-1964 (RH PH 559)

Marcella Huggard

Archives and Manuscripts Processing Coordinator