The tradition of celebrating African American history in February was established in 1926 by Carter G. Woodson, the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. The 2018 theme of Black History Month is “African Americans in Times of War,” and this week we feature two brief excerpts from an oral history interview with WWII veteran William Tarlton. The interview comes from Spencer Research Library’s World War II: The African American Experience oral history interview collection.

More than one and a half million African Americans served in the United States military forces during World War II. They fought in the Pacific, Mediterranean, and European war zones, including the Battle of the Bulge and the D-Day invasion. These African American service men and women constituted the largest number enlisted in the Army and Navy, and the first to serve in the Marine Corp after 1798. World War II: The African American Experience begins to document the experiences of African American World War II veterans through audio recorded interviews. These oral histories are part of the collecting program established by the Kenneth Spencer Research Library’s Kansas Collection in 1986 to enhance the region’s permanent historical record of the African American experience. The collection includes donated materials that provide information about families, churches, organizations and businesses, especially during the 20th century. The World War II oral history project is sponsored in part by the Sandra Gautt KU Endowment Fund, which Professor Emerita Gautt established to honor her father, Sgt. Thaddeus A. Whayne, a member of the Tuskegee Airmen unit.

William Tarlton: Two Oral History Excerpts

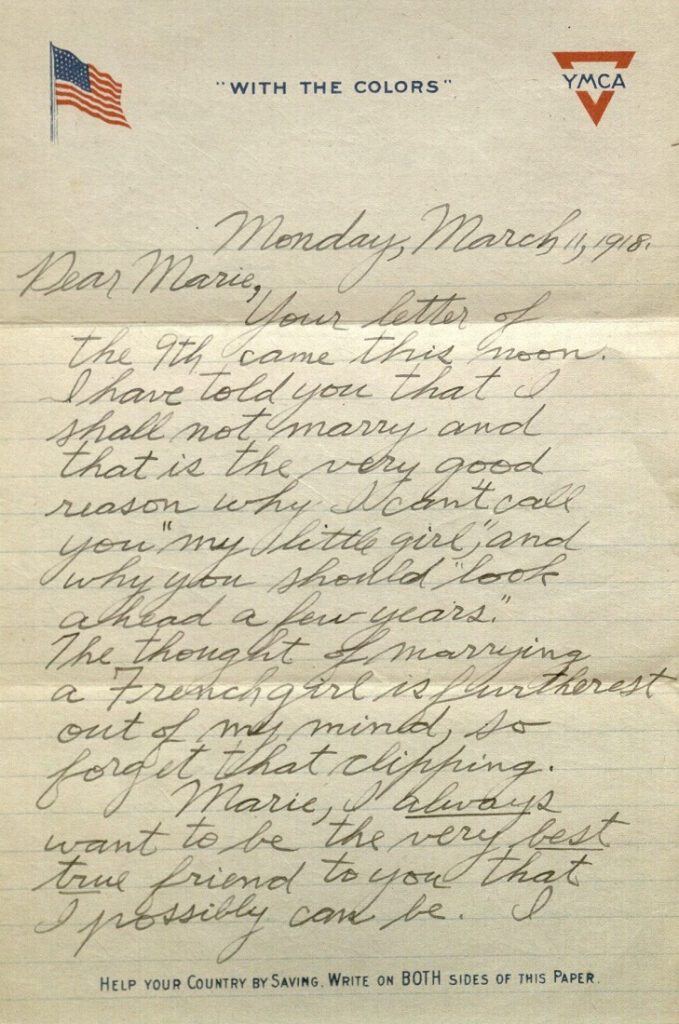

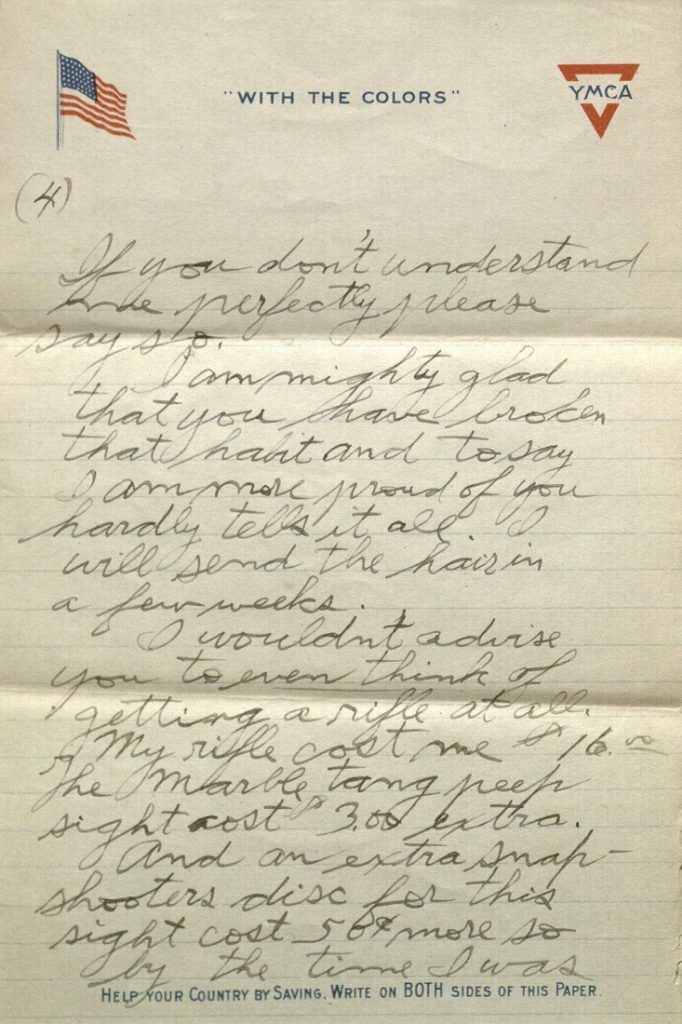

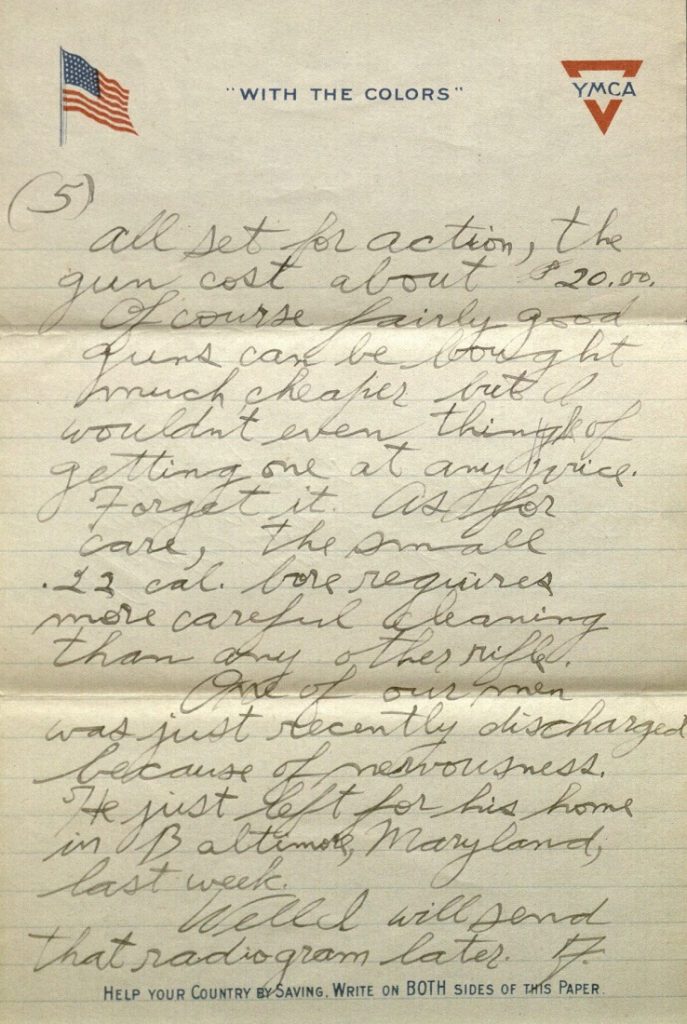

Photograph of William Tarlton from a Squadron F 463rd

Army Air Force photo collage, 1947. Tarlton served with Squadron F

after re-enlisting, following his wartime service with the 371st Infantry.

African American World War II Oral Histories Collection.

Call Number: RH MS-P 1439, Box 1, Folder 3. Click image to enlarge.

A life-long resident of Topeka, Kansas, William Tarlton served in the United States Army’s 92nd Division, 371st Infantry. Wounded twice during the Italian campaign, he was awarded the Bronze Star medal for “his outstanding performance of duty in action against the enemy.” In the passage below, excerpted from his oral history interview with Deborah Dandridge, Field Archivist and Curator for the African American Experience Collections, Tarlton recounts the experience of being shelled.

DANDRIDGE: So when you were training in combat, what sort of things do you remember you had to learn how to do?

TARLTON: Keep your head down. (chuckles) Dig a fox hole. Get in that fox hole or stay on the ground. Yeah.

DANDRIDGE: Did you ever have to do that?

TARLTON: I certainly did. Yes I did. The other one thing that I remember vividly is the fact that I was in, it was a bridge that we went across, that goes across a little creek. And we — me and another guy, one was on one side of the bridge and one was on the other side, I was right there, and three of the artillery shells that fell hit that bridge and they never went off and fell right off into the water. I remember they hit. And see that was, see that German eighty-eight millimeter gun was — you’d hear a “Boo” and next thing it’s on you. You know? Yeah, those are the things that— And that was about, that was one of the, some of the scariest things, especially at night. I mean it’s all dark over there and then — Oh, the other thing that I remember, I was, when I got shrapnel wounds in my arm and back we was getting close to the end of the war and we were up there in a British Signal Corps outfit and we went up in there and they shelled that outfit. And then we were going to get some breakfast that morning. Way off in the field and somehow or other they zeroed in on that thing and you — it just sounded like a pile of lumber falling down.

DANDRIDGE: So you didn’t get your breakfast?

TARLTON: We got it, eventually, after it got all clear. Those British soldiers are resilient people, they’re crazy some of ‘em.

DANDRIDGE: So did you ever, so did you eat with ‘em? Did you eat with the British?

TARLTON: (overlapping) Oh yeah, yeah we ate — I did. And, then me and several of us that was on patrol and we ate down there. Yeah, we did that. And they were very nice. And they were — So one of the things that I can remember that they were, of course I’m young, but the British, they always had some Scotch Whiskey. (chuckles)

DANDRIDGE: And so you all were sharing, is that what you’d say?

TARLTON: They shared a little bit with us.

(William Tarlton Oral History Interview, excerpt from 37:42-40:36)

Over the course of his interview, William Tarlton also discusses segregation in Topeka prior to his service, segregation in the armed forces, and his memories of being at Fort Francis E. Warren, Wyoming when the U.S. military’s new policy of racial integration was implemented after the war. He briefly addresses these last two subjects in our second excerpt:

TARLTON: Well, we were still—We were still in segregated army when I went, in 19— when we got back to the States, we were still segregated. And then we went to Cheyenne, Wyoming and that was where — I can’t remember. I got that on discharge, can’t remember — But, anyway, that was Fort Warren, and it was all, it was segregated out there. They had the white troops over on one side and we was on, we was down on Randall Avenue in nice buildings, nice quarters. And I went to the motor pool and they gave me quarters over there where I started work on those cars, I was along with another couple of soldiers.

DANDRIDGE: Were they white or black?

TARLTON: Oh, two of us—yeah, was white. We— We started getting along real good together because we was in the different area and we all —

DANDRIDGE: So you all socialized together?

TARLTON: Yeah, socialized together and—

DANDRIDGE: Did you ever go out in town?

TARLTON: Not together. That was one of the things that we didn’t do until— See in 1947, when they desegregated the Army, that was 1947 and I was out there when that happened.

DANDRIDGE: What was that like?

TARLTON: Well it was— The only thing, this old white boy come up to me and says—put your clothes down on the side, says “Guess I’m going to bunk beside you.” I said, “Okay.” (chuckles)

(William Tarlton Oral History Interview, excerpt from 58:40-1:00:34)

This interview, recorded on August 12, 2010, is even more striking when you hear William Tarlton’s voice as he recounts his experiences. We encourage you to listen to the entire recording online here, where you will also find a full transcript of the interview.

Once you have explored the World War II: The African American Experience Oral History collection, consider visiting some of the other online resources related to Spencer Research Library’s African American Experience Collections, including the online version of the 2017 exhibition Education: The Mightiest Weapon and the Leon Hughes Photographs digital collection.

Deborah Dandridge

Field Archivist and Curator, African American Experience Collections

Adapted from her text for World War II: The African American Experience