Spencer Rare Materials Cataloging Unit Highlights, January–June 2024

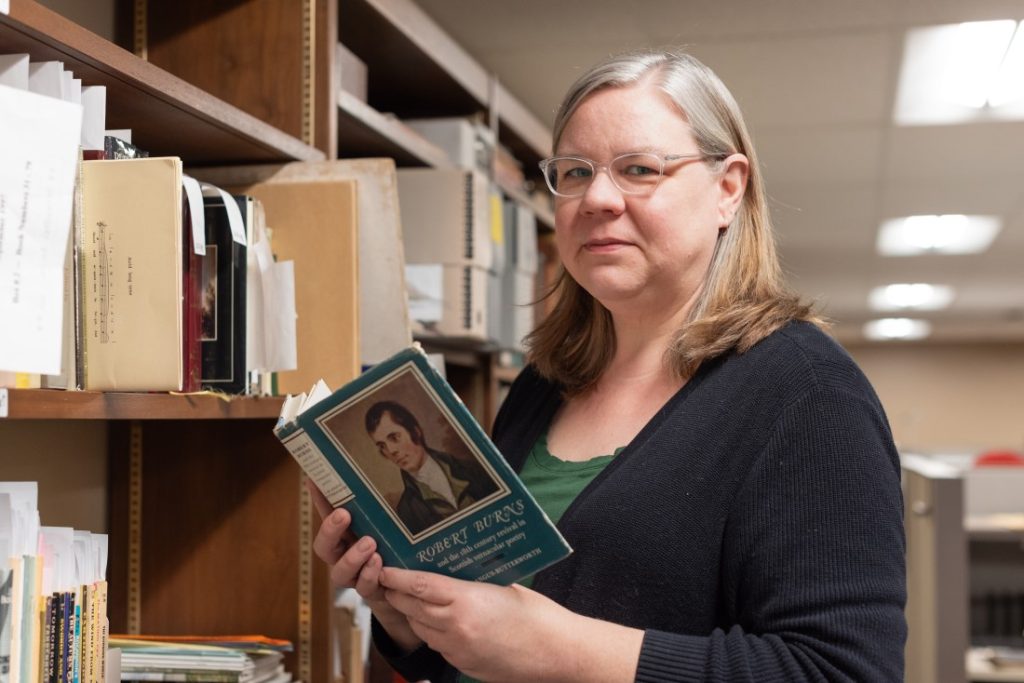

August 21st, 2024The Rare Materials Cataloging Unit at Spencer Research Library describes primary source material across all of the Library’s collecting areas and makes them accessible via the KU Libraries online catalog. We work on a variety of materials from incunabula (books printed in Europe before 1501) to recently produced zines, and a whole lot in between!

The Rare Materials Cataloging Unit documents work in a variety of ways. One way is through the measurement of linear feet, which is one foot or twelve inches. This measurement is used because books – and boxes of archival material – vary in size. Calculating linear feet often means measuring the width of the materials (in inches) as they take up physical space on shelves and then dividing by twelve. We use the “Guidelines for Standardized Holdings Counts and Measures for Archival Repositories and Special Collections Libraries” (PDF) – a professional standard from the Rare Books and Manuscripts Section of the American Library Association and the Society of American Archivists – as guidance for managing these counts.

Below are the linear feet equivalents of materials we have completed working on for each Spencer Research Library collecting area from roughly January 1, 2024 through June 30, 2024.

We’ve handled 2428 items during that time, amounting to a little over 176 linear feet (2112.65/12). You can picture this as a line of books stretching almost sixty yards down a football field. See the breakdown below:

| Collecting Area | Number of Items | Size (inches) |

|---|---|---|

| University Archives | 62 | 98.6 |

| Kansas Collection | 614 | 446.3 |

| Special Collections | 1198 | 1355.85 |

| Wilcox Collection | 554 | 211.9 |

| TOTALS | 2428 | 2112.65 |

Of the backlogged materials (anything arriving prior to June 2022) cataloged in the first six months of 2024, the two longest-waiting items were El Hallazgo, purchased from Otero Muñoz in 1972 (Call Number: Griffith Q116), and Blätter der Rilke-Gesellschaft, no.1, 1972, purchased from the Schweizerisches Rilke-Archiv in 1973 (Call Number: Rilke Y1113).

The heaviest item we’ve cataloged since June 2022 is the fine press photo book Antarctica, which was created by Pat and Rosemarie Keough to save the albatross (Call Number: H480).

Highlights for each collecting area include the following:

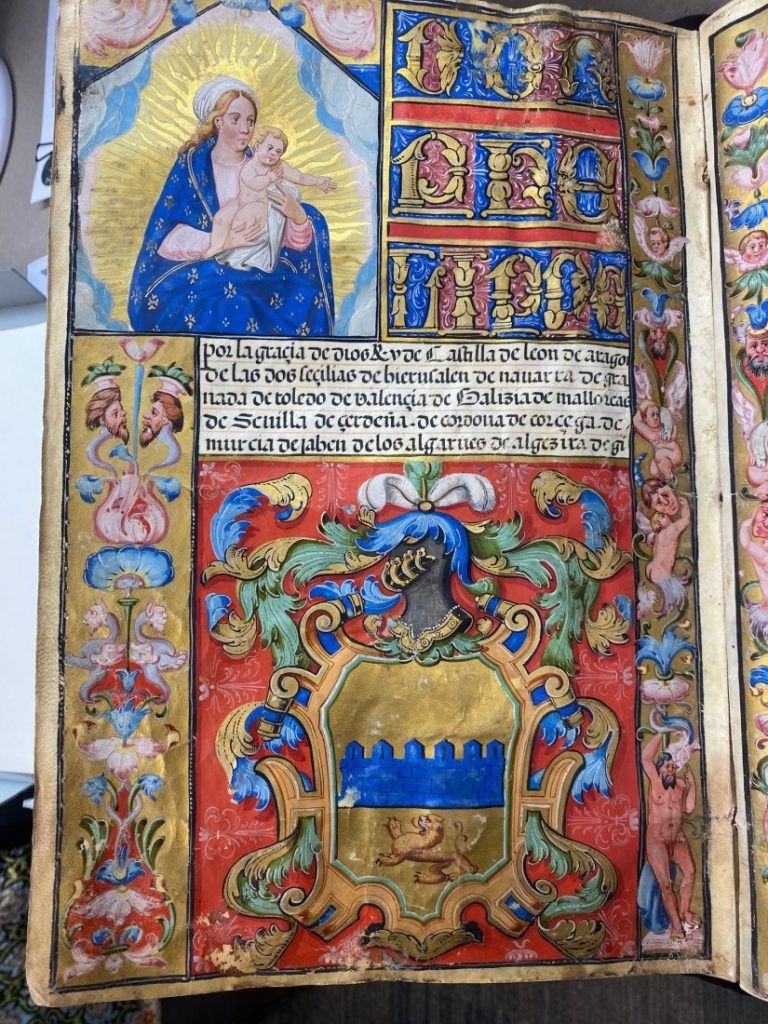

- For Special Collections: Carta executoria de hidalguía de Lazaro de Adarve, 1570 (Call Number: MS E289), an early modern manuscript that arrived with a detached lead seal.

- For University Archives: The Jayhawk: The Story of the University of Kansas’s Beloved Mascot, the 2023 book publication by our much-loved prior University Archivist, Becky Schulte (Call Number: GV691.U542 S35 2023).

- For the Kansas Collection: American Winds: Chicago’s Pioneering Black Aviators and the Race for Equality in the Sky (2024) by Sherri L. Smith, Spencer Research Library’s 2020 Alyce Hunley Wayne travel awardee (Call Number: RH C12791), and Head Jobs, Vol 1-5 (2022-2024), a serial zine publication by a local Lawrence, Kansas, zine-maker (Call Number: RH Ser C1591).

- For the Wilcox collection: Wonders of Nature (2023), an experimental sound recording (Call Number: WL AV10).

Jaime Groetsema Saifi

Special Collections Cataloging Coordinator