Manuscript of the Month: Vergil’s Aeneid and the Mathematics of Bookmaking

February 26th, 2021N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

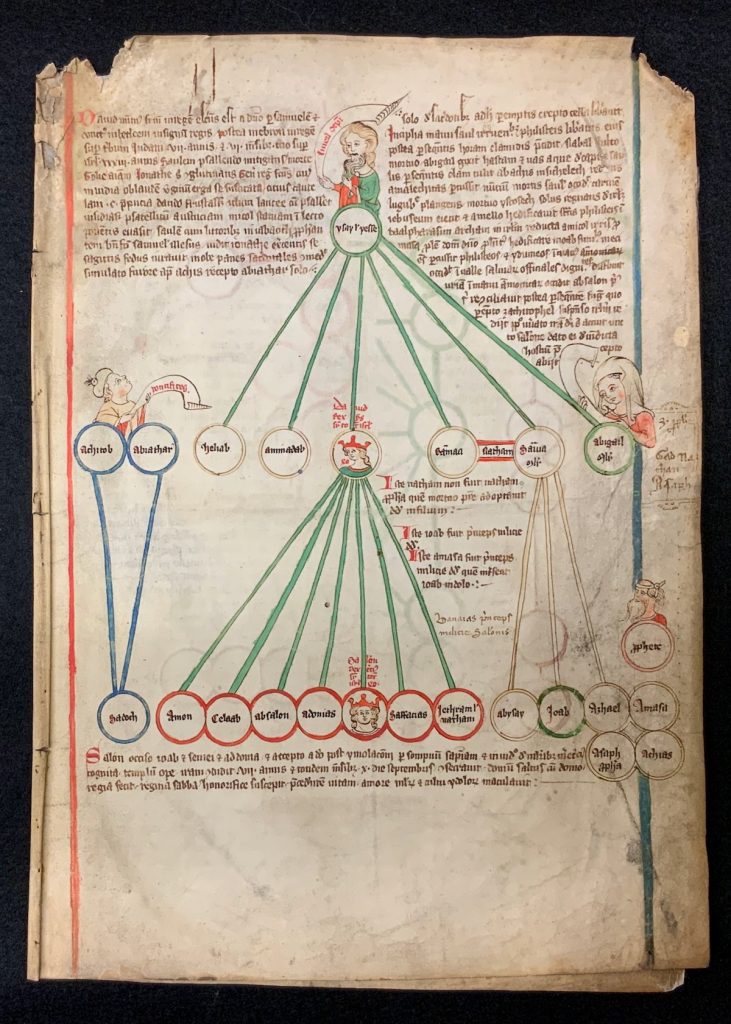

One of the first manuscripts I looked at after I started working at the University of Kansas in September 2019 was Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS E71. Since I am equally interested in the reception of the Trojan War in the Middle Ages and the history of the book, this incomplete copy of the Aeneid was the perfect choice. The Aeneid is an epic poem in twelve books composed between 29 and 19 BCE by Publius Vergilius Maro (70 BCE-19 BCE), more commonly known as Vergil or Virgil. It tells the story of Aeneas, a Trojan who travelled to Italy after the fall of Troy and who is considered to be the ancestor of the Romans.

Vergil’s Aeneid was probably the most read and most consulted classical work during the Middle Ages and beyond. One could even go as far as to say that Vergil’s Aeneid is probably the most well-known classical work of all times. It was used as part of the curriculum in Latin probably almost immediately after its composition for centuries to come. Even today, if one were to learn Latin anywhere in the world, it is more than likely that this is the first text one would encounter in class. And, if you learned Latin with Vergil, even if you forgot everything else, you would probably still remember the opening words of the poem: “Arma virumque cano” (“I sing of arms and the man”). Romans of the first century certainly were familiar with this phrase, as this is one of the most common texts found among the graffiti that survive on the walls of the ancient city of Pompeii, which was buried under volcanic ash and pumice following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79!

MS E71 was probably copied in the first quarter of the fifteenth century in Italy, many centuries after its composition. The state of the manuscript as we have it reflects the rich history of reading, writing and ownership of the manuscript over the past five hundred years, with its leaves full of annotations by previous users and owners. It is also incomplete, missing several leaves, perhaps another indication of heavy use of the manuscript over the centuries. One of the reasons why this manuscript holds a special place in the collections of the Kenneth Spencer Research Library is that MS E71 is part of a larger gift from Robert T. Aitchison (1887-1964). The manuscript was donated along with 42 rare printed editions of Vergil’s works, one of which is an incunabulum dated to 1487 (Aitchison D1). A native Kansan, Aitchison was an artist and a book collector, and served as the president and director of the Kansas Historical Society among other things. Aitchison had purchased the manuscript from Bernard M. Rosenthal in July 1961, a mere two years before he gifted it to the University of Kansas Libraries along with the rest of his collection of Vergil’s works.

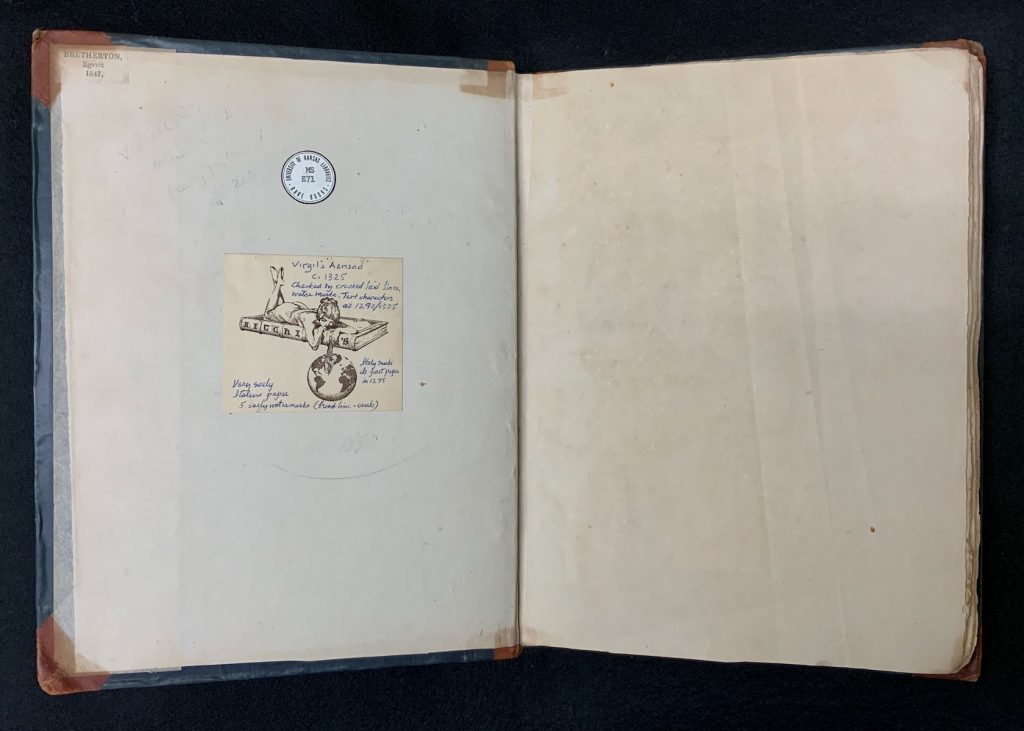

Bookplate of Robert T. Aitchison in the middle and the ticket of the binder, George Bretherton, in the upper left corner of the front pastedown (left). Vergil, Aeneid, Italy (?), first quarter of the fifteenth century?. Call # MS E71. Click image to enlarge.

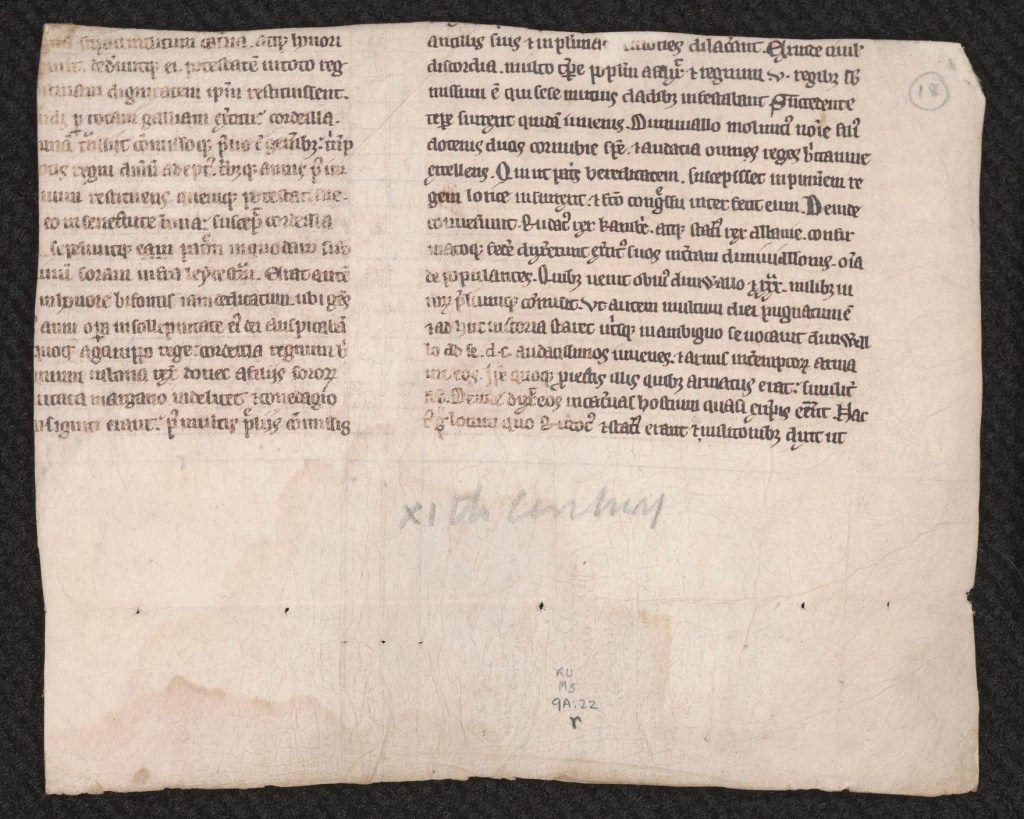

In the previous century, MS E71 was in the collection of another prominent book collector: Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792–1872). It is estimated that Sir Thomas had some 40,000 printed books and 60,000 manuscripts in addition to paintings, prints, photographs and other materials, which makes him the owner of the largest private collection of manuscripts in the world in the nineteenth century, or perhaps ever. The Kenneth Spencer Research Library preserves a number of manuscripts from the former Phillipps collection, which were dispersed during the years after the Phillipps’s death, such as MS C247, about which I had previously written a blog post.

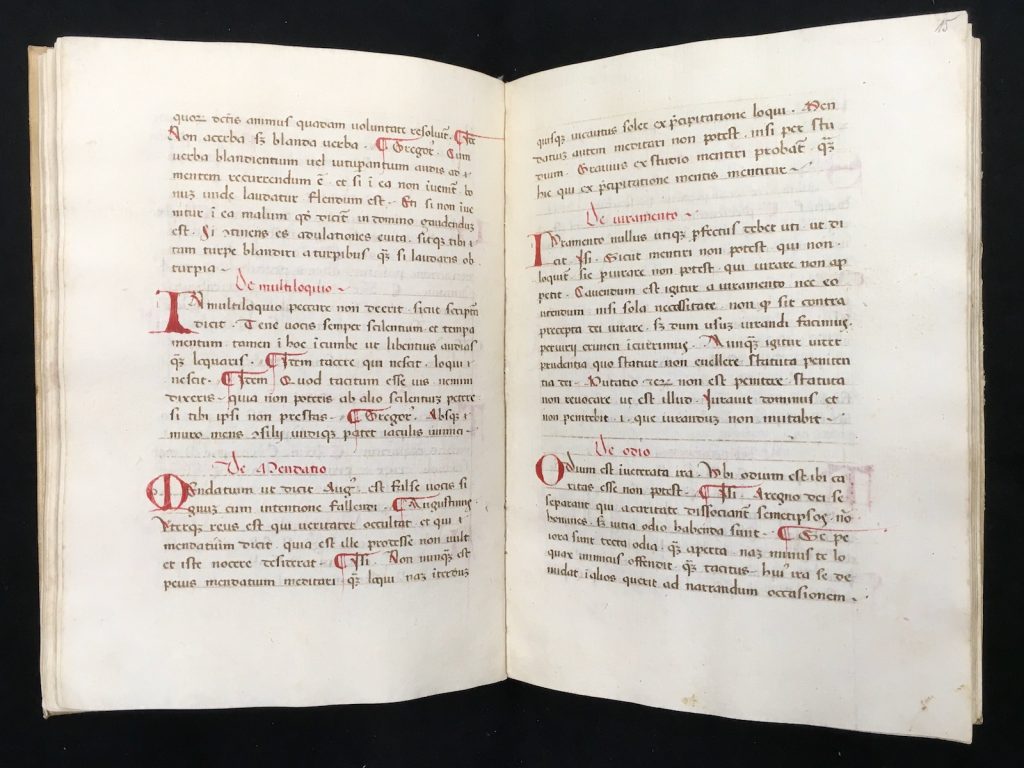

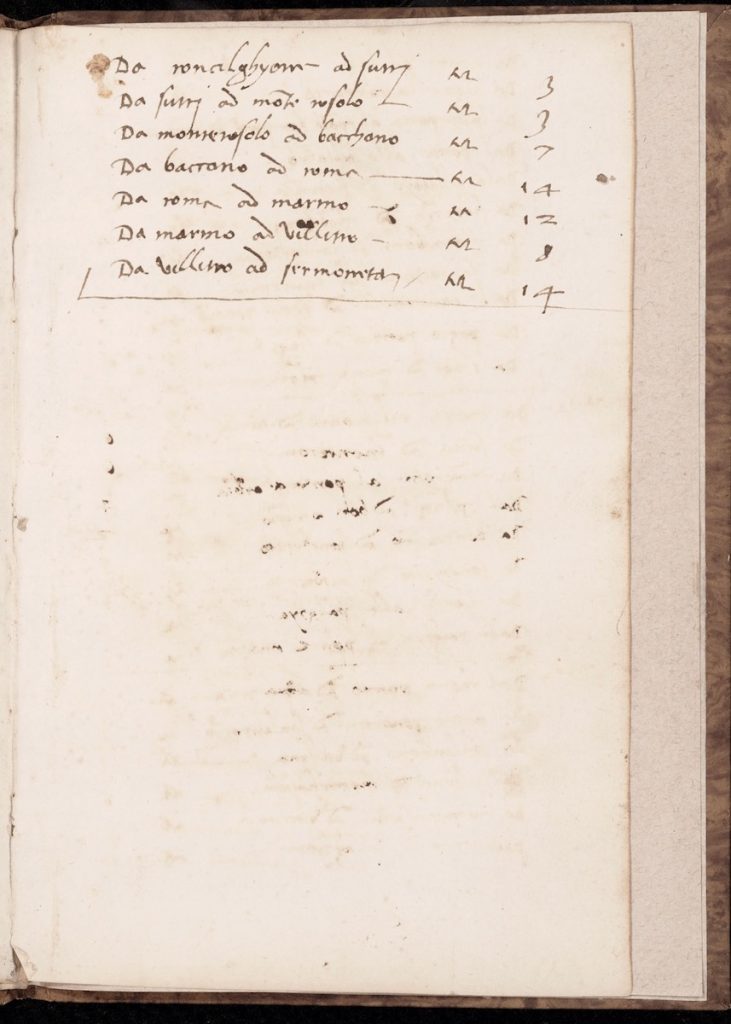

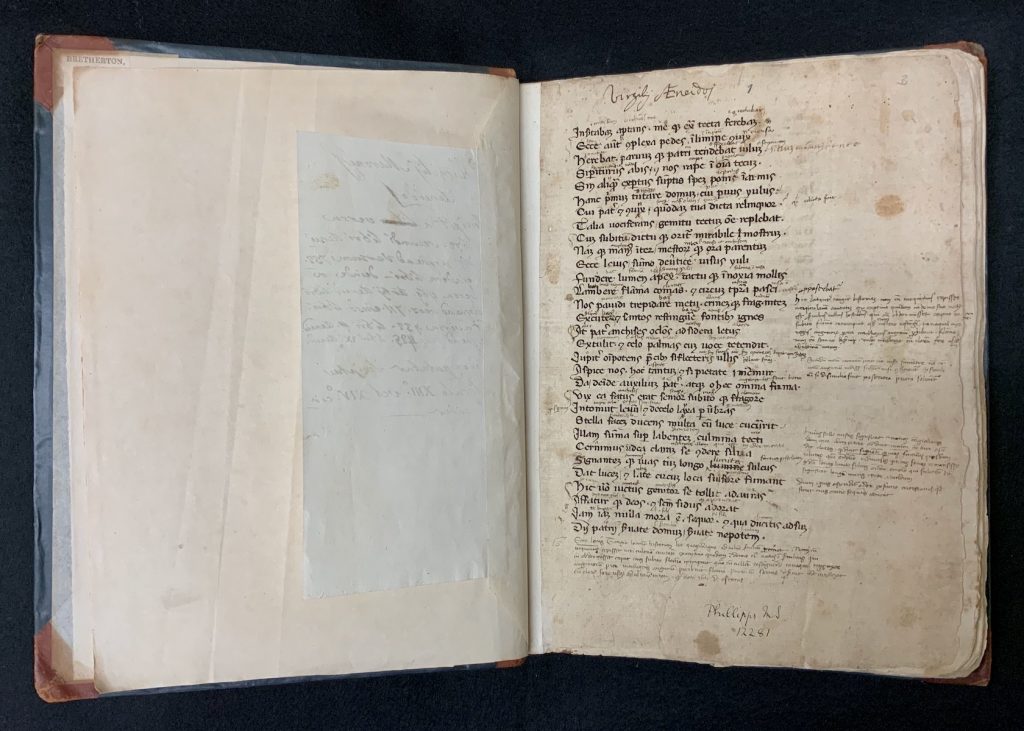

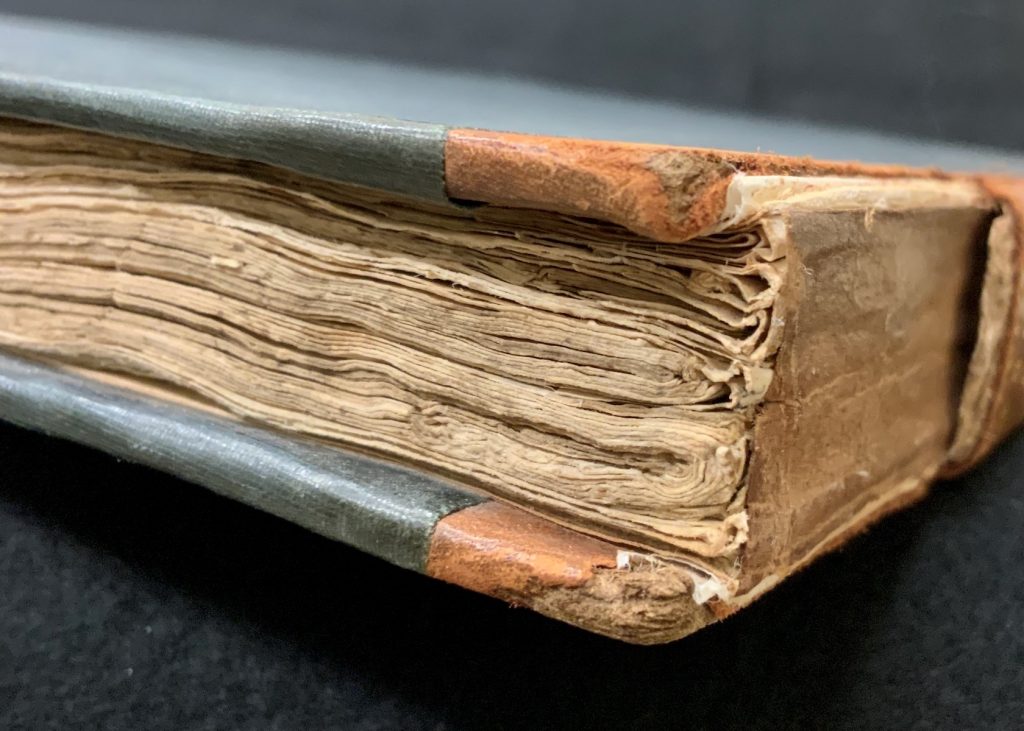

According to surviving records, Sir Thomas Phillipps purchased the manuscript from Payne & Foss, an antiquarian bookseller based in London who was instrumental in procuring many of the manuscripts in his collection. It is inscribed in Phillipps’s usual manner as “Phillipps MS 12281” in ink on the lower margin of the recto of the first leaf. MS E71, a paper manuscript of currently 67 leaves, must have been unbound at the time of its purchase. It seems that it was immediately rebound by a binder who used to work for Phillipps, George Bretherton. The manuscript still has this mid-nineteenth-century half calfskin and blue cloth binding, with the binder’s ticket intact in the upper left corner of the front pastedown: “BRETHERTON, ligavit 1847” [BRETHERTON, bound 1847].

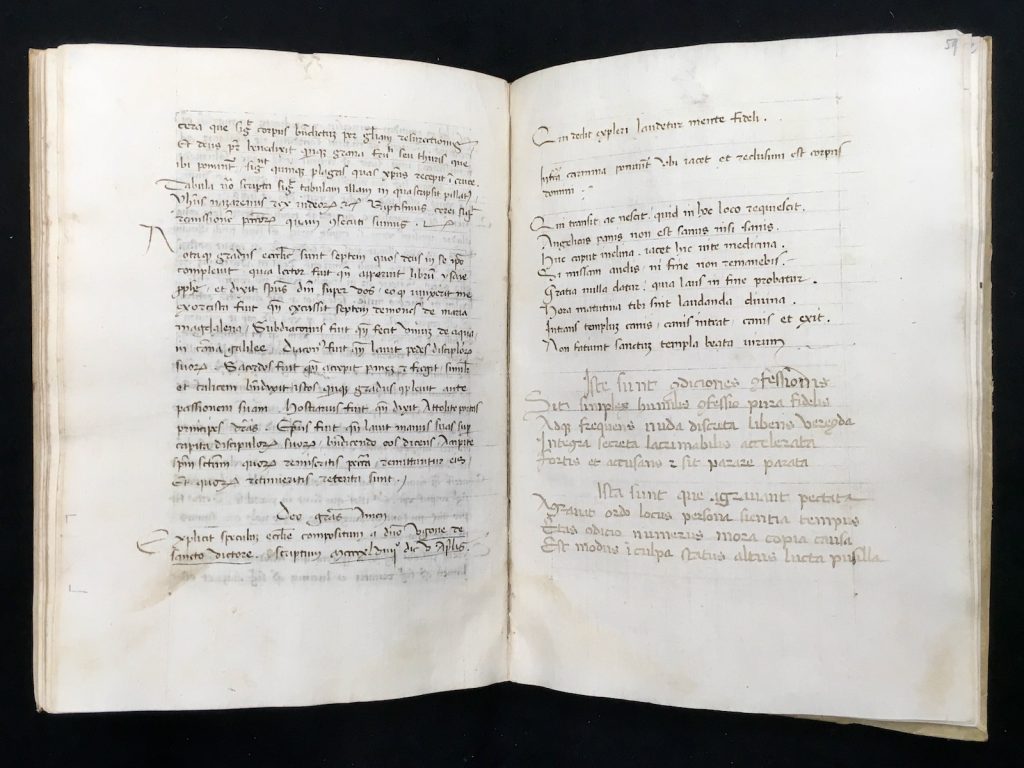

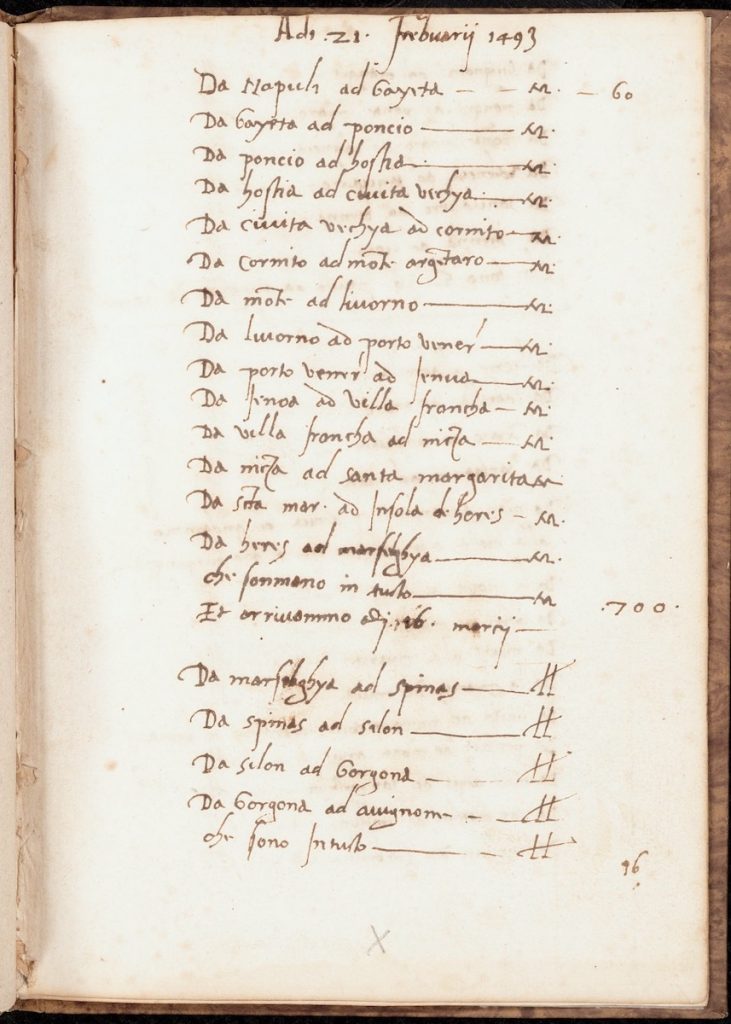

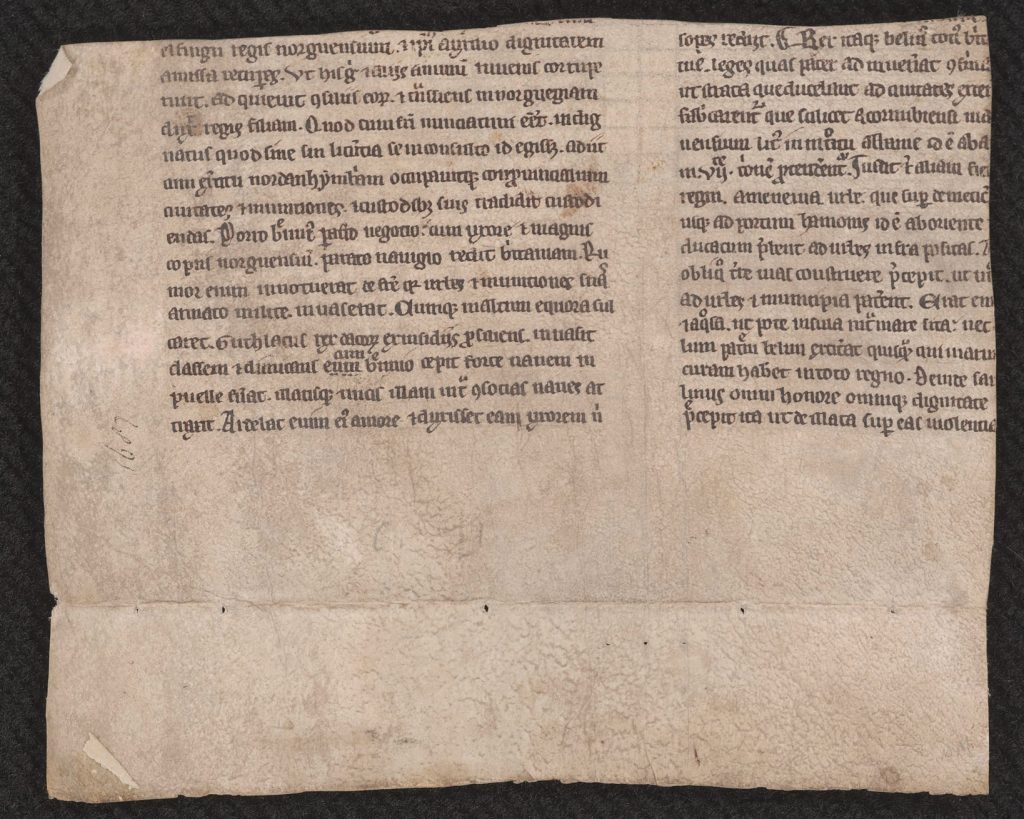

MS E71 seems to have undergone heavy repairs in the nineteenth century, presumably during Bretherton’s rebinding process. As part of these conservation efforts, various tears and holes on the leaves seem to have been mended, usually by pasting pieces of modern paper on top of the damaged parts of the medieval paper. More importantly, paper strips were adhered to the center-folds and spine-folds of most of the leaves to support the integrity of the book. Single leaves that were presumably detached from the bookblock were also glued to other leaves, forming artificial gatherings. And finally, a lining was adhered to the spine before the book was bound. Because of all of these interventions and the rearrangement of the quires during the rebinding, the original design of the manuscript is now completely altered. For example, the current first folio of the manuscript contains Book II, lines 672-732 of the Aeneid whereas the second folio begins on Book III, line 469. So, clearly there are several leaves missing between these two leaves which now follow each other, but one would not be able to tell this immediately just by looking that the manuscript.

Due to the current condition of the manuscript, it is difficult ascertain not only which leaves originally went together as conjoint leaves but also how the manuscript was collated, that is, what the structure of the gatherings originally were. Thus, in this case, a physical examination of MS E71 alone does not help one to understand how the manuscript was actually put together.

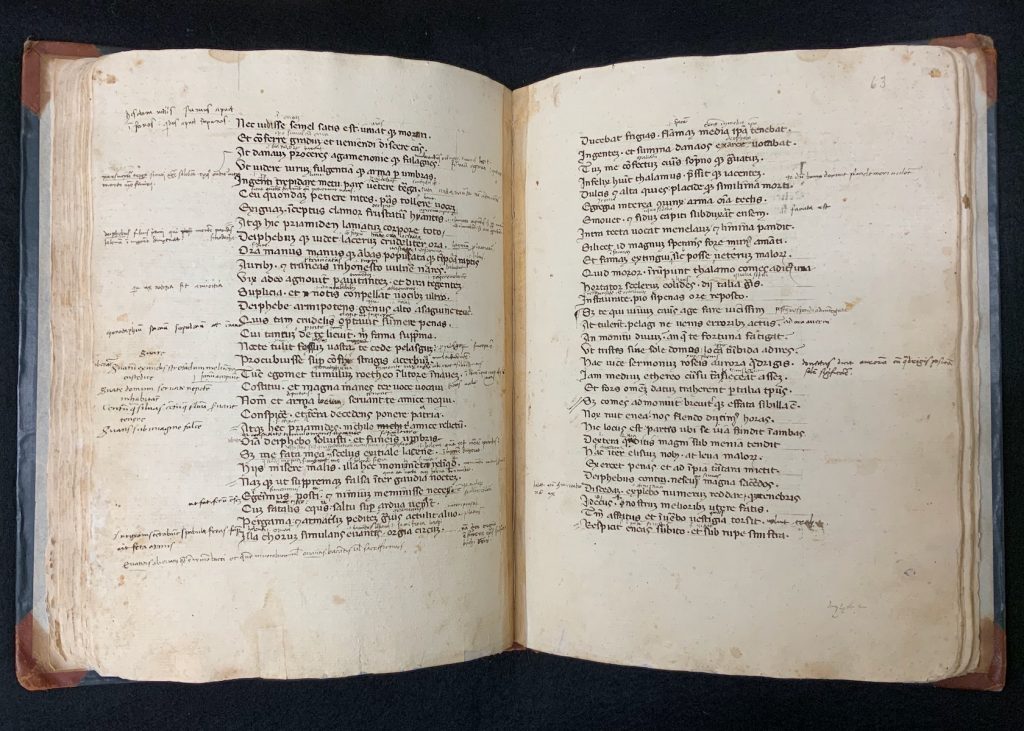

In the past two millennia, the Aeneid was copied in manuscripts thousands of times and printed in various editions also by the thousands since its first print edition in 1469. Although there are a variety of differences on the word level in these copies, the work as a whole is fairly well-established since the early Middle Ages. That MS E71 contains this well-known work is very useful in this case because it means that we have a good understanding of how long the text is and that we can identify what parts of the manuscript are lost and even estimate how many leaves are missing. It is also helpful that the Aeneid is a verse text, meaning that each line in a given copy also would correspond to a line in this manuscript and that there would be no variations on the length of the text depending on the density of the script or the size of the leaves.

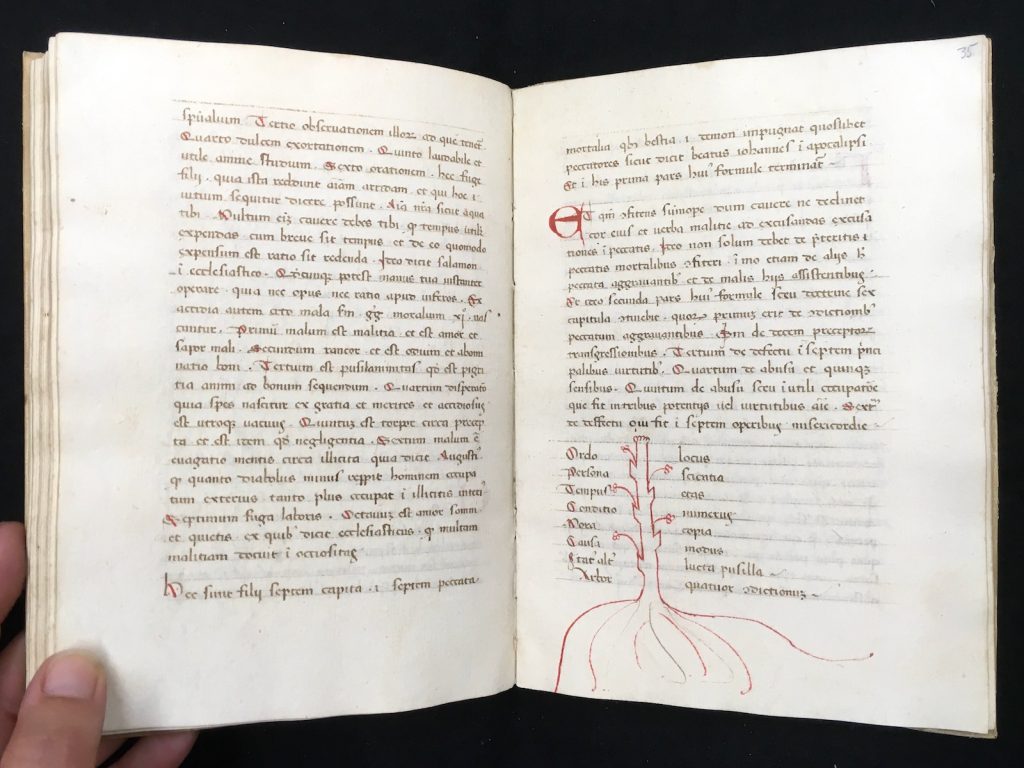

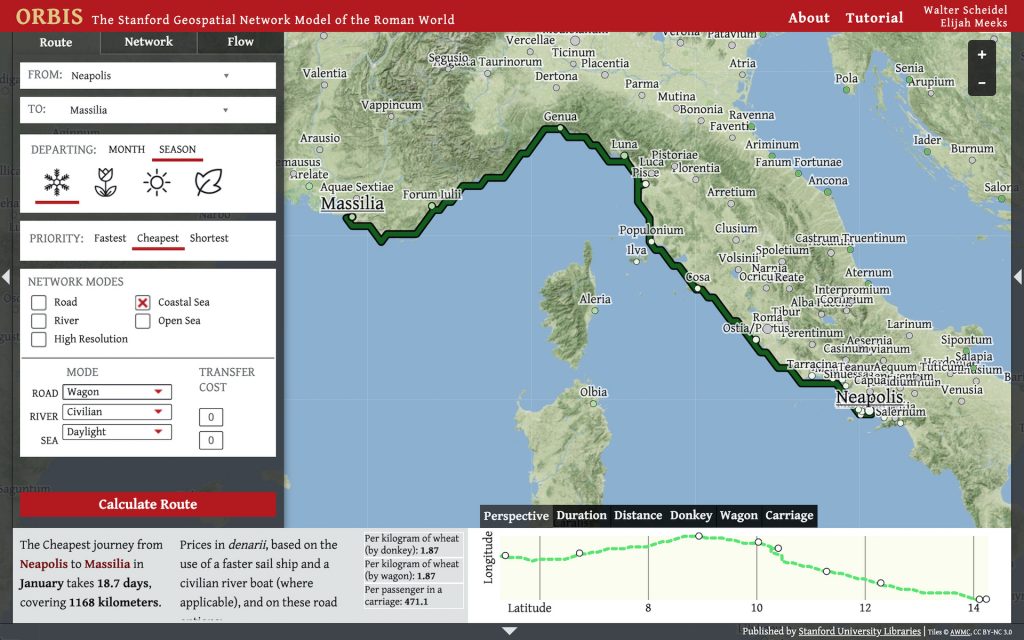

In order to compare the text of the Aeneid as we have it in MS E71, I used the Greenough edition dated to 1900, which is available open access via the Perseus Digital Library of Tufts University. The Aeneid consists of twelve books, with each book having a different number of lines. In this edition, Book I has 756 lines, Book II 804 lines, Book III 718 lines, Book IV 705 lines, Book V 871 lines, Book VI 901 lines, Book VII 817 lines, Book VIII 731 lines, Book IX 818 lines, Book X 908 lines, Book XI 915 lines and Book XII 952 lines. So, if one were to copy the entire text of the Aeneid with no break, one would copy 9896 lines of text. If one were writing 29 to 30 lines per page, the average in MS E71, then one would end up filling about 168 leaves. Ideally, such a manuscript could have been arranged in quires of 12 leaves, for example, which would make up 14 gatherings, or in quires of 8 leaves which would make up 21 gatherings.

The text as we have it in MS E71 begins on line 672 of the second book of the Aeneid (now folio 1r). This means that, at the very least, the first 671 lines of Book II as well as the entirety of Book I (756 lines) are missing. The last line we have in MS E71 is Book IX, line 425 (now folio 67r). Ordinarily, one would think that the rest of the work was also missing from the manuscript; however, since the copying ends on the recto of a leaf and the verso is left blank, we can surmise that the scribes of this manuscript abandoned the project on Book IX, line 425 and did not copy the entirety of the Aeneid. Thus, if they copied the text continuously up to that point, they would have had 6728 lines. We can estimate therefore that originally MS E71 must have had at least 114 folios. Therefore, it is currently lacking at least 47 leaves, 24 of which are almost certainly from the beginning. We may never be able to confidently reconstruct the original collation of MS E71, but with the help of a little bit of mathematics, we can at least point to the possible number of missing leaves and where they are missing in the manuscript!

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library was gifted the manuscript by Robert T. Aitchison in July 1963, and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

Further literature to explore:

- Editions and translations of Vergil’s Aeneid on Perseus Digital Library: [open access]

- Craig W. Kallendorf. A Bibliography of the Early Printed Editions of Virgil, 1469-1850. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll, 2012. [KU Libraries]

- The Phillipps Manuscripts: Catalogus librorum manuscriptorum in bibliotheca D. Thomae Phillipps, BT. Impressum Typis Medio-Montanis, 1837-1871. London: Holland Press, 1968. [KU Libraries]

- A. N. L. Munby. The Dispersal of the Phillipps Library. Phillipps Studies 5. Cambridge: University Press, 1960. [KU Libraries]

- L. R. Lind. The R. T. Aitchison Collection of Vergil’s Works at the University of Kansas Library, Lawrence. Wichita, KS: Four Ducks Press, [1963]. [open access by KU Libraries]

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.