With the end of summer, and the start of school just around the corner, perhaps you are thinking about squeezing in just one more road trip. Maybe you’d like to explore a state you’ve never been to, or get to know the one you’re in a little better. You’ll need a good, concise guidebook for the journey, one with interesting facts and historical information, as well as reliable maps and tourist information. To start with, you might consider consulting the American Guide Series. Although they were published from the late 1930s through the mid-1940s, they still provide excellent background information to get you started, although you’ll probably want to get an up-to-date map.

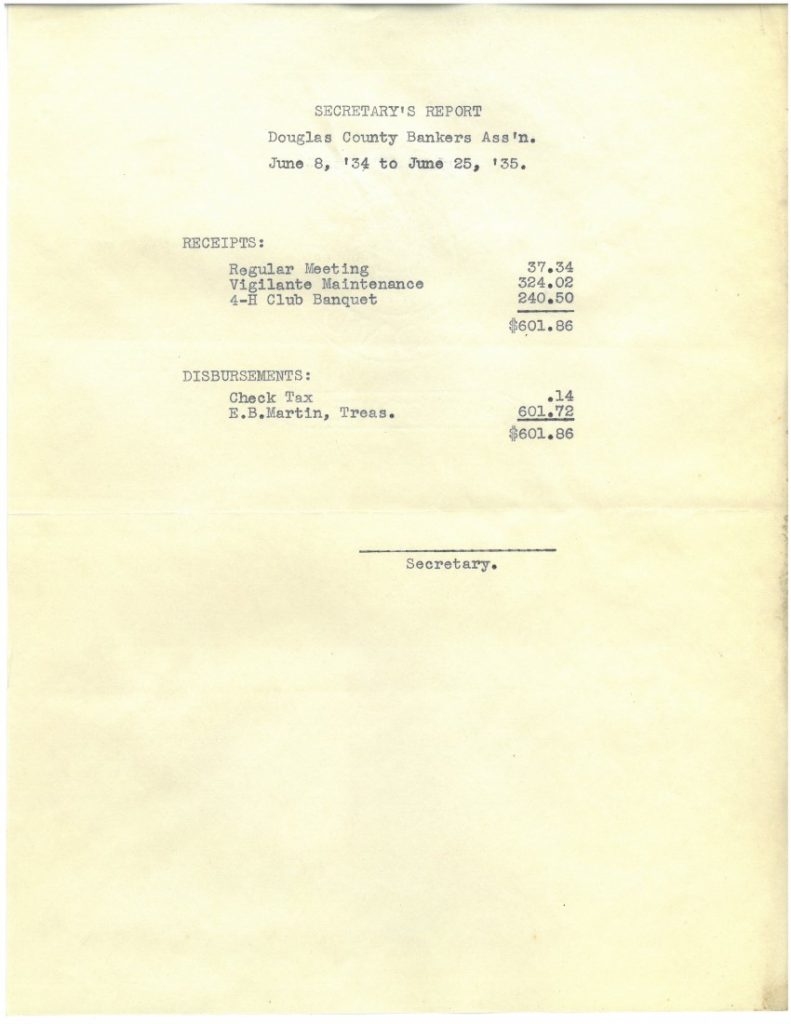

American Guide Series for Missouri (1941), Colorado (1946), Nebraska (1939),

and Kansas (1939). Call Numbers: RH C9550, RH C11457,

RH C11415, and RH C11429. Click image to enlarge.

When Franklin Roosevelt became our 32nd president in 1933, the biggest national issue he and his administration had to contend with was the country’s severe economic depression, then in its fourth year with no end in sight. The plan they came up with to address this predicament became known as the New Deal, and it put in place a series of programs created by Congress and by presidential executive order to provide relief, recovery, and reform, all aimed at getting people back to work and the national economy on its feet again. The Works Progress (later Projects) Administration (WPA) was the largest of the New Deal agencies.

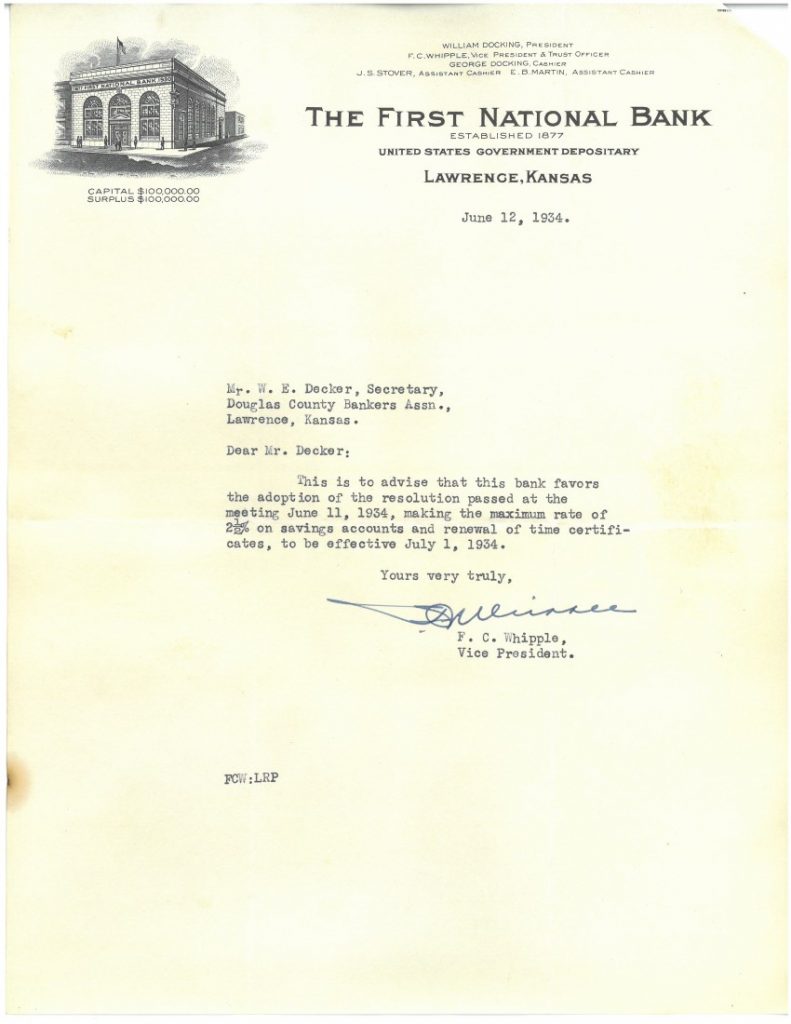

Fold-out map of Kansas from the American Guide Series volume on the state, 1939.

Call Number: RH C11429.Click image to enlarge.

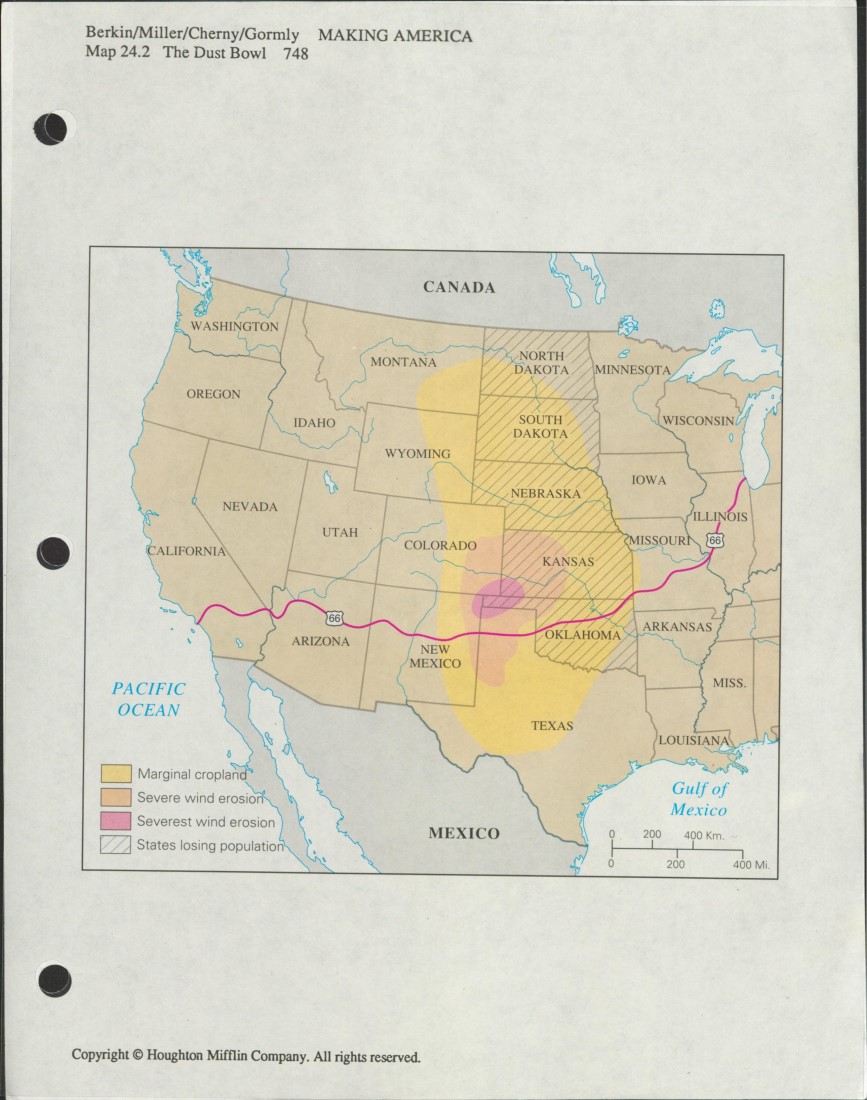

One of those WPA projects was the agency called the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP). Begun in 1935 and ending in 1943, the FWP, at its peak, employed approximately 6,600 unemployed writers, editors, researchers, historians, art critics, archaeologists, geologists, cartographers, and clerical workers. They produced more than 276 books, 701 pamphlets, and 340 other publications, such as articles, leaflets, and radio scripts. The most popular of these works was the American Guide Series. Each state, through the FWP, hired staff to create a guidebook that contained information about the state’s history, cities, landmarks, and historic sites; the culture of its people; and the geology and geography of the land. Each guidebook also contained a detailed highway map, usually folded up at the back of the book. In addition to the states, guidebooks were created for the territories (except Hawaii) and large cities, such as Washington, D.C. and New York. Some states, including Kansas, were able to create guidebooks for a few of their towns, as well. For their time, there is also a surprising amount of information about minority populations in the guidebooks, although often stereotypical and exploitative. The goal of the guidebooks was to familiarize Americans with their own state and country and to keep them in the United States on their vacations, where their tourism dollars were most needed.

Title page of American Guide Series for Washington, D.C., 1937.

Call Number: RH C3424. Click image to enlarge.

Title pages for American Guide Series for Leavenworth (1940) and Larned (1938), Kansas.

Call Numbers: RH C4787 and RH C4999. Click image to enlarge.

Describing the Series, Harry Hopkins, federal relief administrator, perhaps said it best when he asserted (as quoted in Catherine A. Stewart’s Long Past Slavery):

The American traveler gets into his automobile and travels for four days…and has the conviction that there is nothing of interest between New York and Chicago. Outside of a few highly advertised [sites]…he isn’t conscious of what America contains, of what American folk habits are. Americans are the most travel-minded people in the world; but their travel is two percent education and 98 percent pure locomotion. Speeding through towns whose chain stores look as if they had been turned out on an assembly line, the American motorist is unaware of the infinite variety and rich folklore of the American scene…For the first time, we are being made aware of the rich and varied nature of our country…By producing books that are helping us to know our country, the Writers’ Project helps us become better acquainted with each other and, in that way, develops Americanism in the best sense of the word.

Sources:

Hobson, Archie. Remembering America: A Sampler of the WPA American Guide Series. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

Shortridge, James R. The WPA Guide to 1930s Kansas. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1984.

Stewart, Catherine A. Long Past Slavery: Representing Race in the Federal Writers’ Project. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

Kathy Lafferty

Public Services