Celebrating Banned Books Week at Spencer

October 9th, 2025This week week, October 5-11, is Banned Books Week, an advocacy initiative started by the American Library Association’s Intellectual Freedom Committee in 1982 at the suggestion of the Association of American Publishers, who were facing many censorship efforts by the religious right at the time. Libraries across the country celebrate this week with banned book displays and events that bring attention to the fact that our freedom to read is still under attack. KU’s Watson Library currently has a display of banned books, and KU students can check the Libby app for a list of e-books and audiobooks that are commonly challenged.

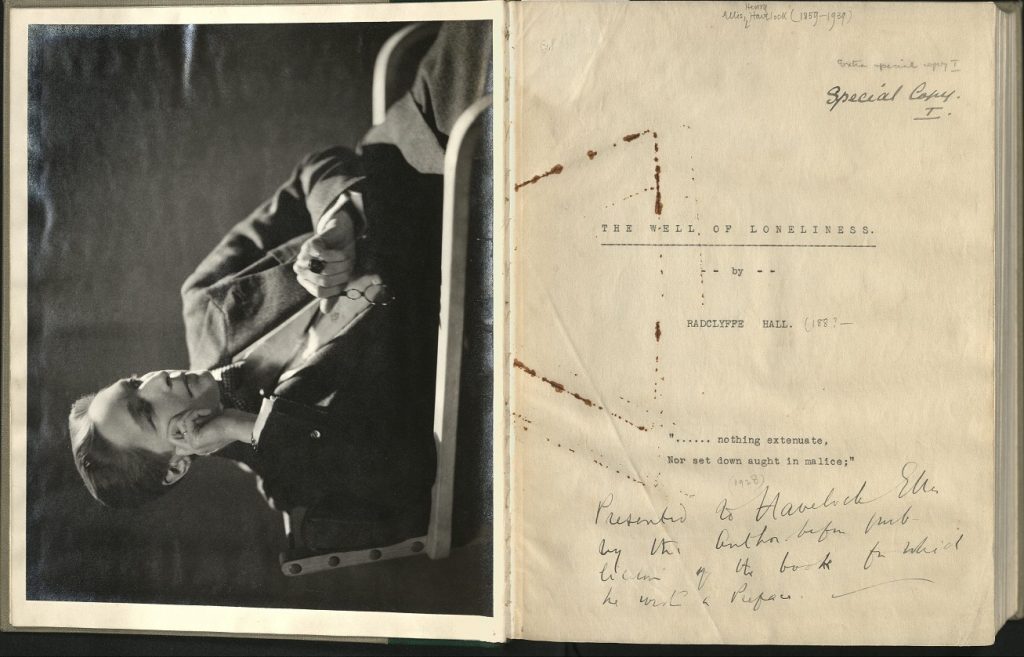

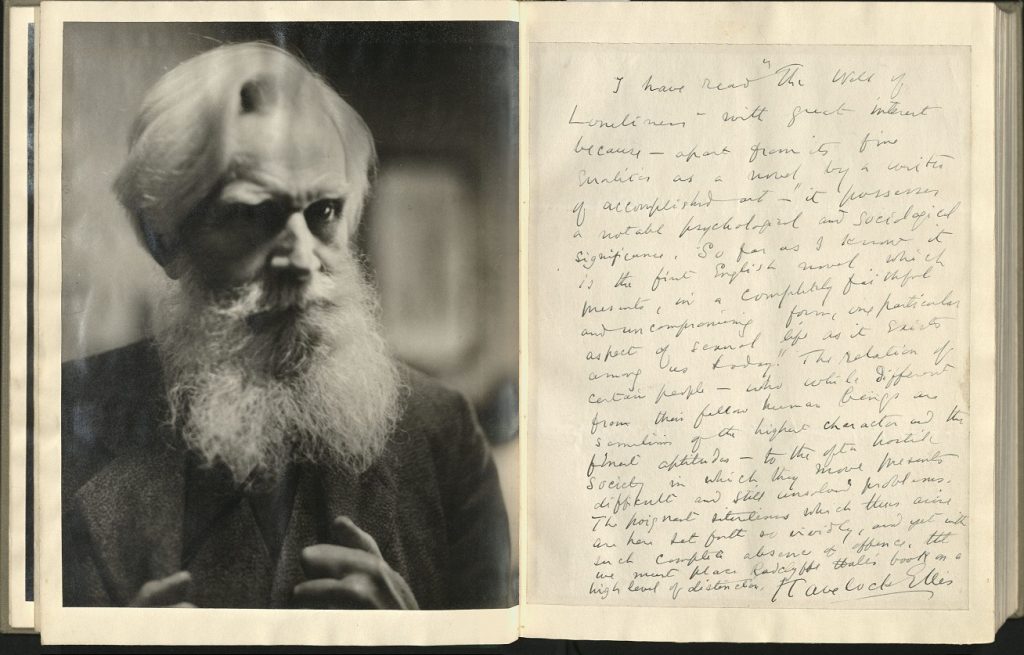

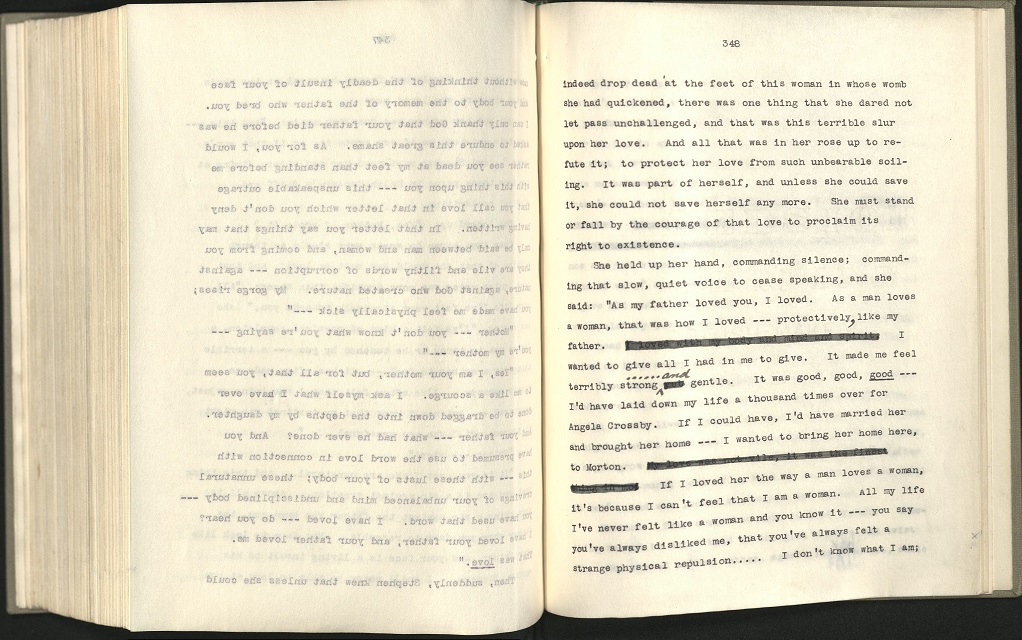

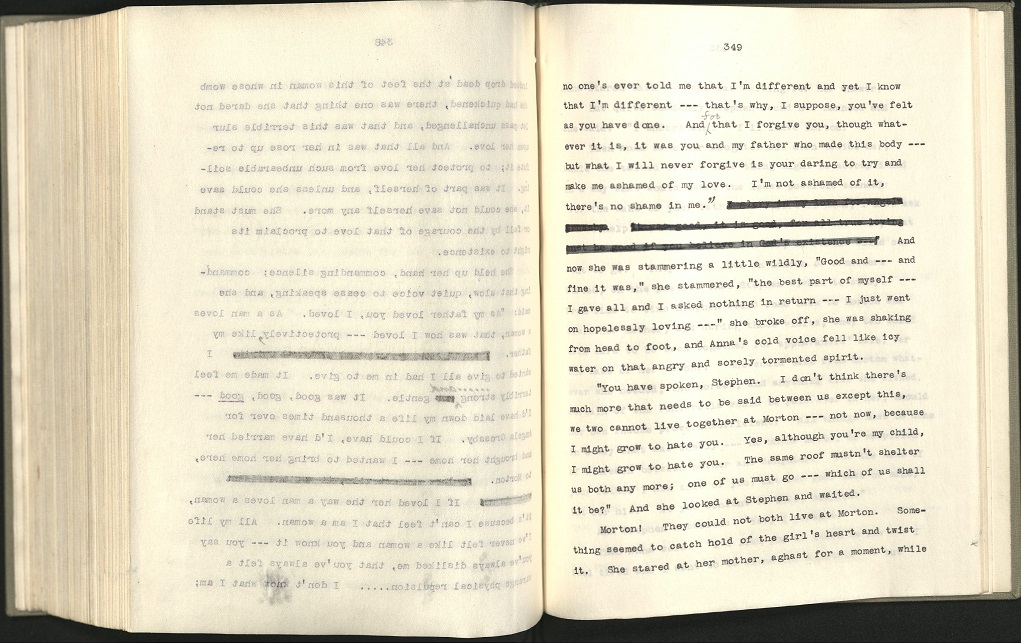

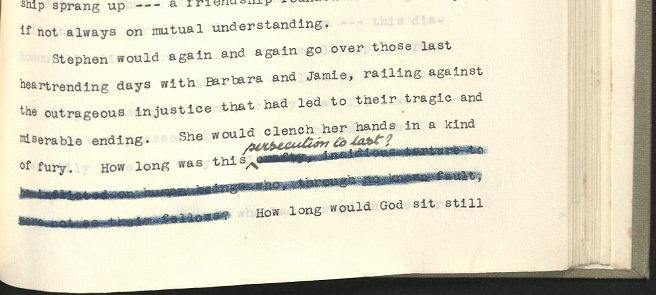

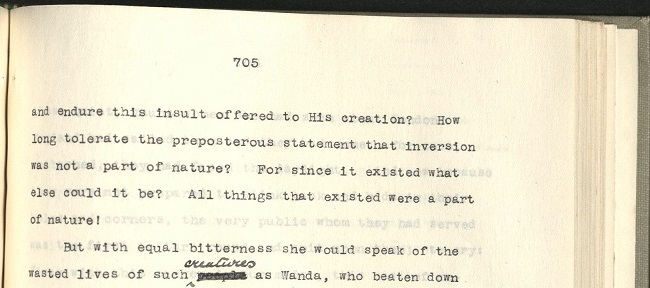

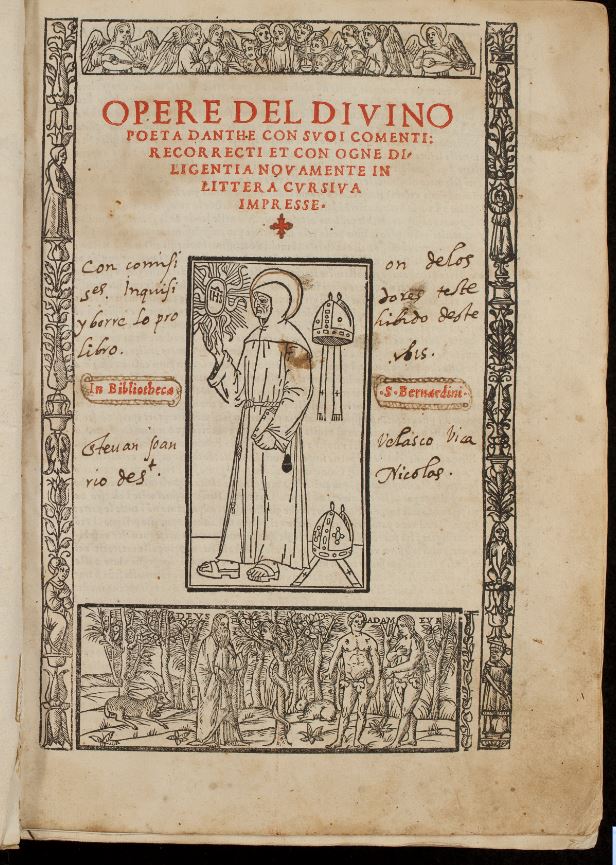

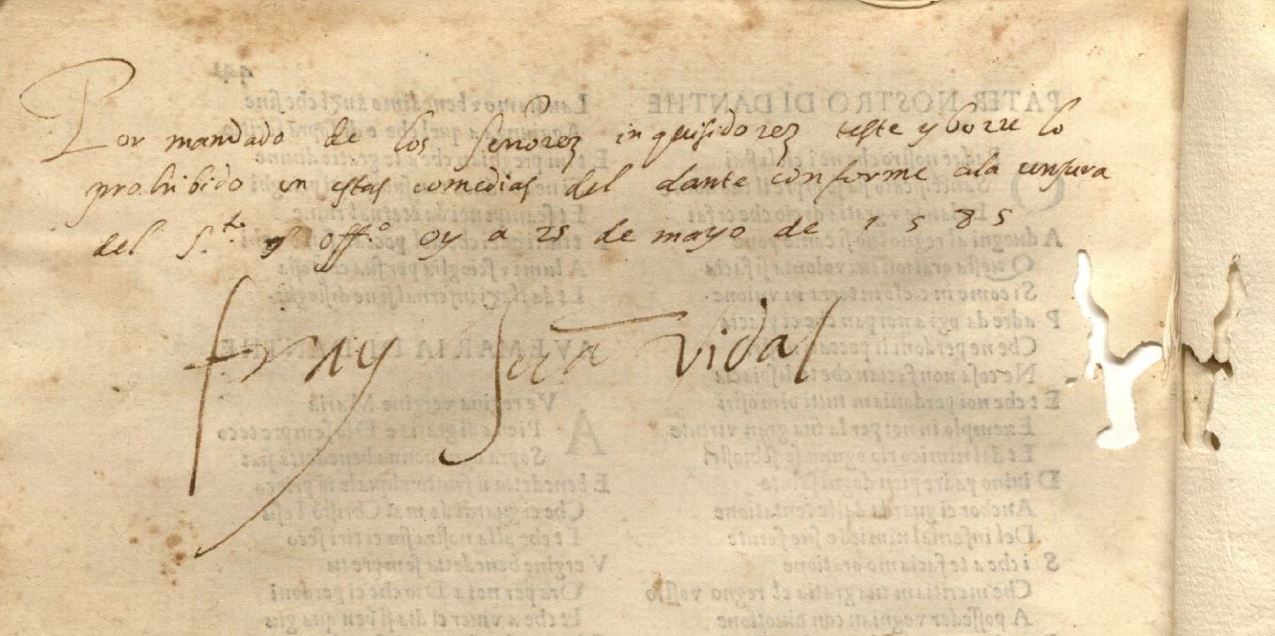

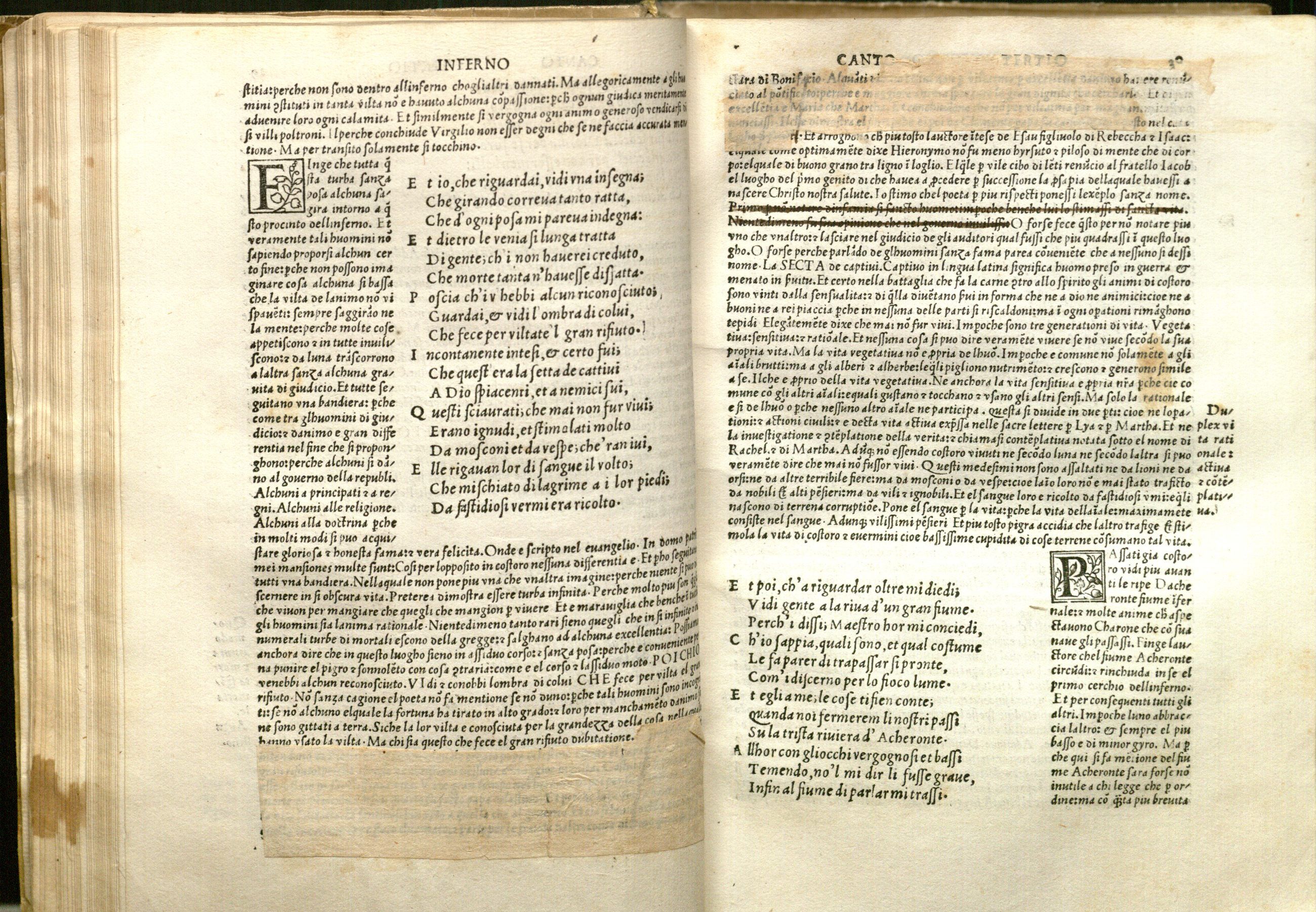

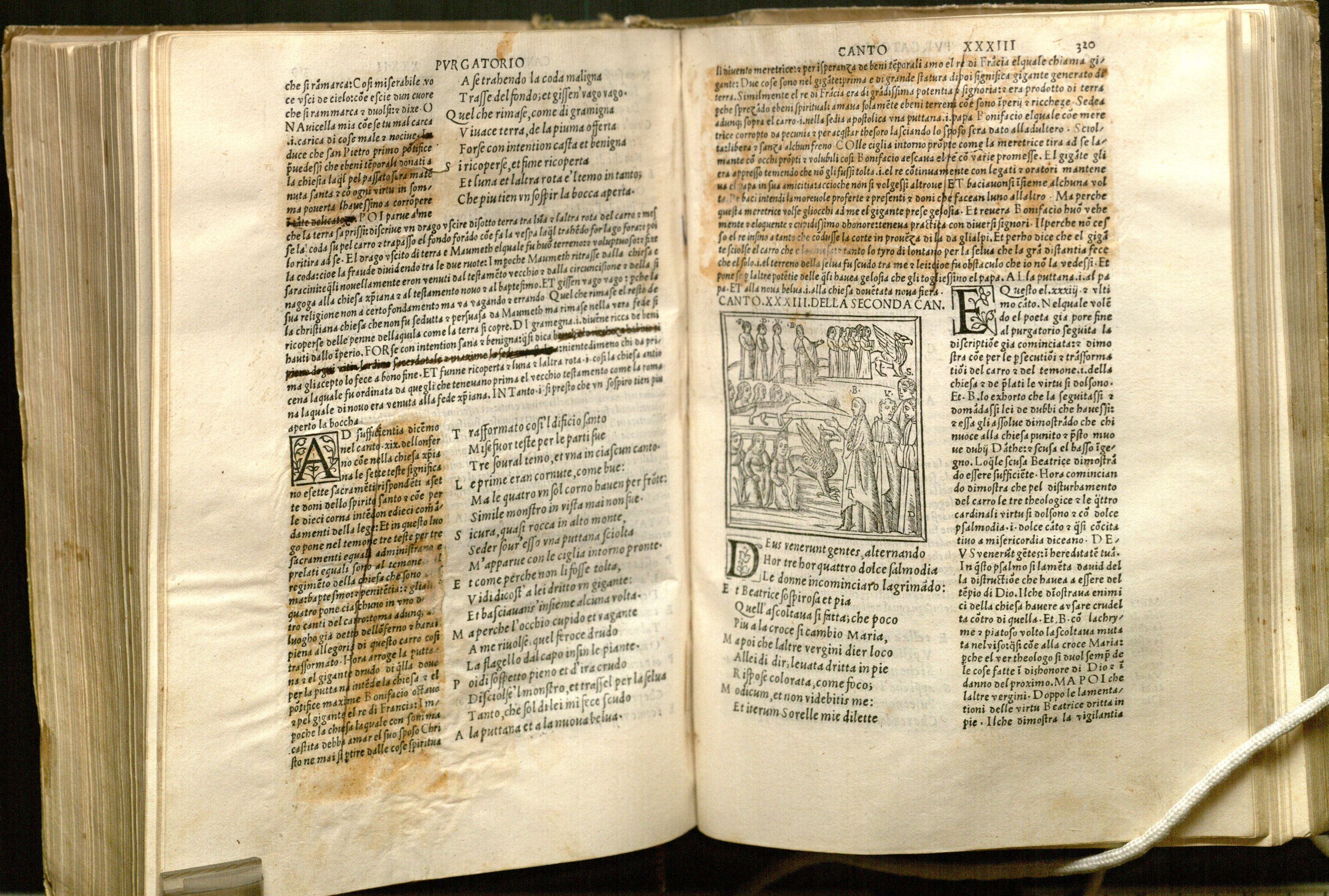

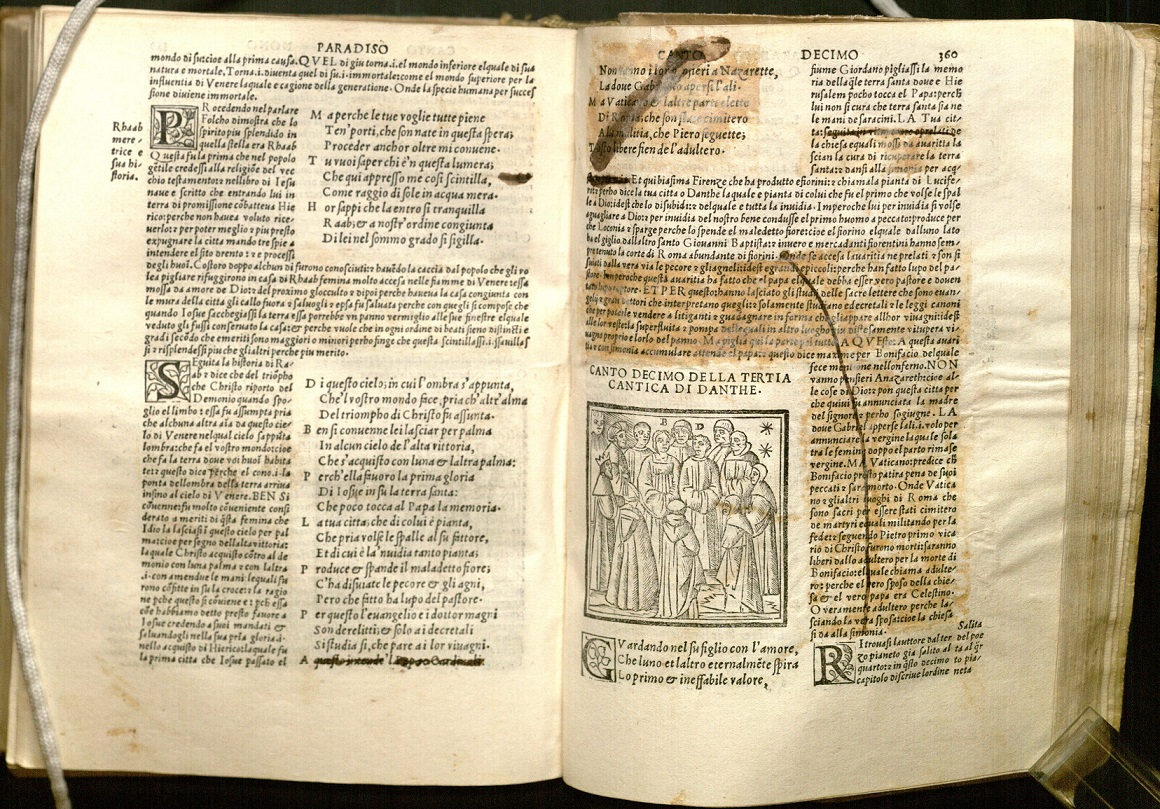

Spencer Research Library holds many classic books that are often challenged or banned in schools, including first and special editions of Fahrenheit 451, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and Naked Lunch. Beyond novels, Spencer also collects material for the Wilcox Collection of Contemporary Movements that would otherwise be banned in many contexts or far outside a typical public or school library’s collecting policies.

The Wilcox collection was started by Laird Wilcox, a student at KU in the 1960s who was interested in politics and concerned about free speech. He started collecting flyers, newsletters, and books from organizations on the political margins, including communist groups and right-wing leaders. As the chair of KU’s Student Union Activities Minority Opinions Forum, he brought several controversial speakers to campus, including neo-Nazi activist George Lincoln Rockwell. The 1964 event caused heated debate among students and faculty about free speech and what was appropriate on college campuses. (The Wilcox Collection includes photographs and cassette tapes from this event and Wilcox’s interview with Rockwell.) Wilcox’s experiences at KU as a student activist led him to collecting political material he feared would be banned or otherwise unavailable. He continued collecting until his death in 2023.

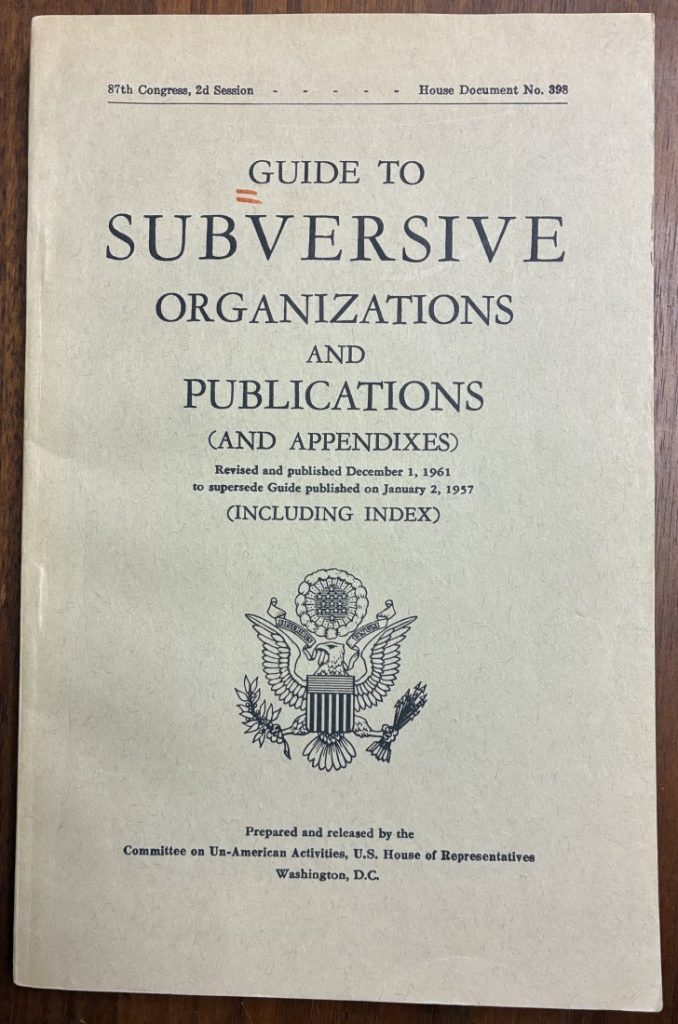

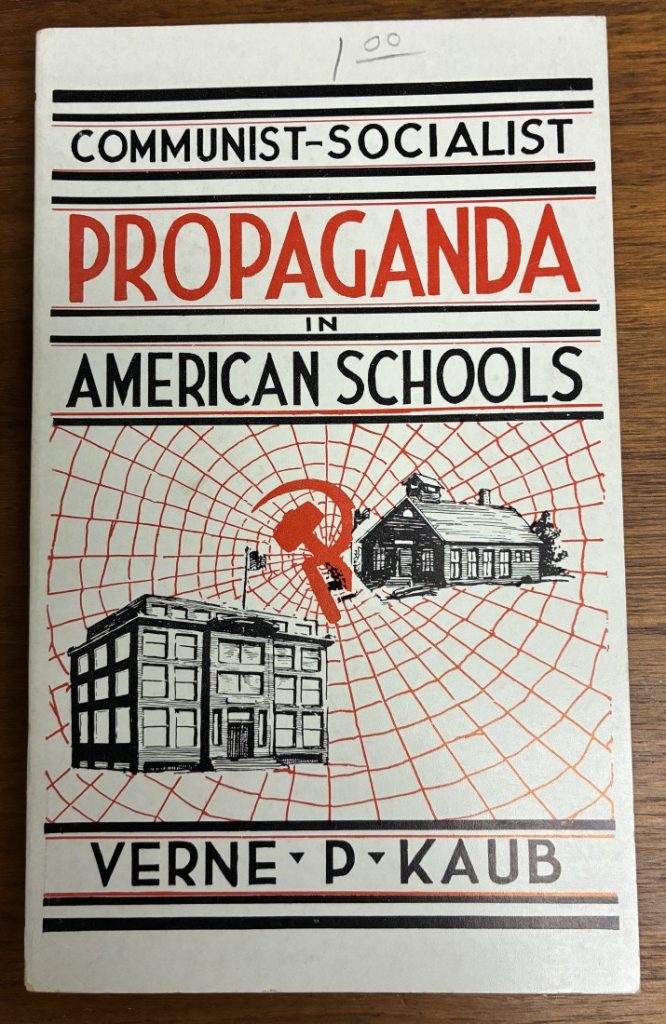

To find these kind of publications, Wilcox used directories like the Guide to Subversive Organizations and Publications, which was issued by the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Un-American Activities (known as HUAC) and revised several times throughout the 1950s and early ‘60s. This directory included summaries of organizations with citations to HUAC’s own committee reports and records. Although this directory and others like were often used by librarians to censor their own collections, Wilcox used it essentially as a catalog. He also purchased books published by right-wing organizations and individuals on their beliefs that schools, government bodies, or other organizations were brainwashing Americans, especially children, with left-wing propaganda like Communist-Socialist Propaganda in American Schools by Verne P. Kaub. These were also useful for tracking down material, as they often included lists of titles and directions on how to (ironically) acquire them to review for censorship efforts in local communities. Wilcox also collected books, periodicals, and ephemera by organizations devoted to free speech that tracked censorship like Censorship News to help make collecting decisions and acquire material that is now available at Spencer.

By corresponding and meeting with booksellers and people who belonged to these groups, Wilcox expanded his circle of contacts to acquire more “subversive” books and material. He was able to facilitate acquisitions of unpublished manuscript materials from key figures in both left-wing and right-wing movements like Willis Carto (founder of the Liberty Lobby) and other collectors such as Albert and Angela Feldstein (who specialized in left-wing buttons, stickers, and posters). The Wilcox Collection now includes many formats beyond books such as photographs, audiovisual material, and more.

In his later life, after developing a reputation as an expert on propaganda and free speech, Wilcox wrote his own books on political extremism and compiled bibliographies of propaganda and books of quotations on censorship, propaganda, and freedom of speech. These publications are also available at Spencer in the Wilcox Collection.

The former Curator of the Wilcox Collection, Becky Schulte, wrote about Laird Wilcox, the history of the collection, and her efforts to expand it in a presentation to the Society of American Archivists in 2016, titled “Curating the Controversial: The Wilcox Collection of Contemporary Political Movements, University of Kansas.” She details the acquisition of the collection of James Mason, a key figure in white supremacist movements, and both the difficulties and professional satisfaction involved in curating such a collection.

The librarian Mary Jo Godwin said that “a truly great library contains something in it to offend everyone,” a quote that is now widely circulated on social media during Banned Books Week and in other discussions of censorship. Due to the decades of tireless effort by both Laird Wilcox and Becky Schulte, we can say that the Spencer Research Library is among the best of truly great libraries.

Kate Stewart

Curator of the Wilcox Collection of Contemporary Political Movements