Banned Books Week: The Well of Loneliness

September 28th, 2018It’s the end of September, which means that it’s Banned Books Week (this year, September 23-29th), an annual celebration of the freedom to read. Among the most frequently challenged books in recent years have been ones that include LGBTQ content or themes, such as same-sex relationships or issues surrounding gender identity. (Four of the 2017 and five of the 2016 top ten most challenged books, as compiled by the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual Freedom, were challenged in part for LGBTQ subject matter.) With this in mind, today we feature a typescript from Spencer’s collections for a novel that stands as a landmark in the history of lesbian literature and the history of censorship, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928).

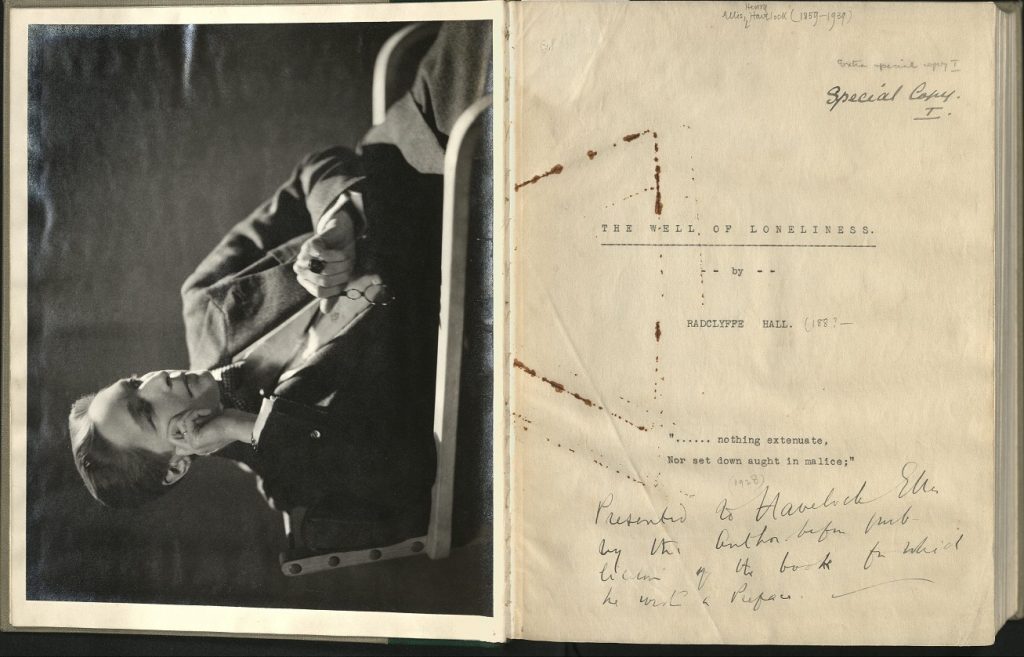

The Well of Loneliness tells the story of Stephen Gordon as she struggles to find love and acceptance in a society that rejects same-sex desire. Often discussed as the first openly lesbian novel in English, The Well of Loneliness favors the term “invert” over lesbian. The novel’s author, the British writer Radclyffe Hall, imported this word from late nineteenth and early twentieth century writings of sexologists such as Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Havelock Ellis. Indeed, Havelock Ellis wrote a prefatory comment for Radclyffe Hall’s novel, and Spencer Research Library’s typescript copy appears to have been given by Hall to Ellis. It includes a manuscript copy of Ellis’s introductory “comment,” and is marked “Special Copy I” in Radclyffe Hall’s hand on the title page. Photographic portraits of both Hall and Ellis have been added to the typescript, perhaps by some later owner.

Photograph of Radclyffe Hall pasted next to the title page of a typescript of her novel The Well of Loneliness. England, approximately 1928. Call #: MS D45. Click image to enlarge.

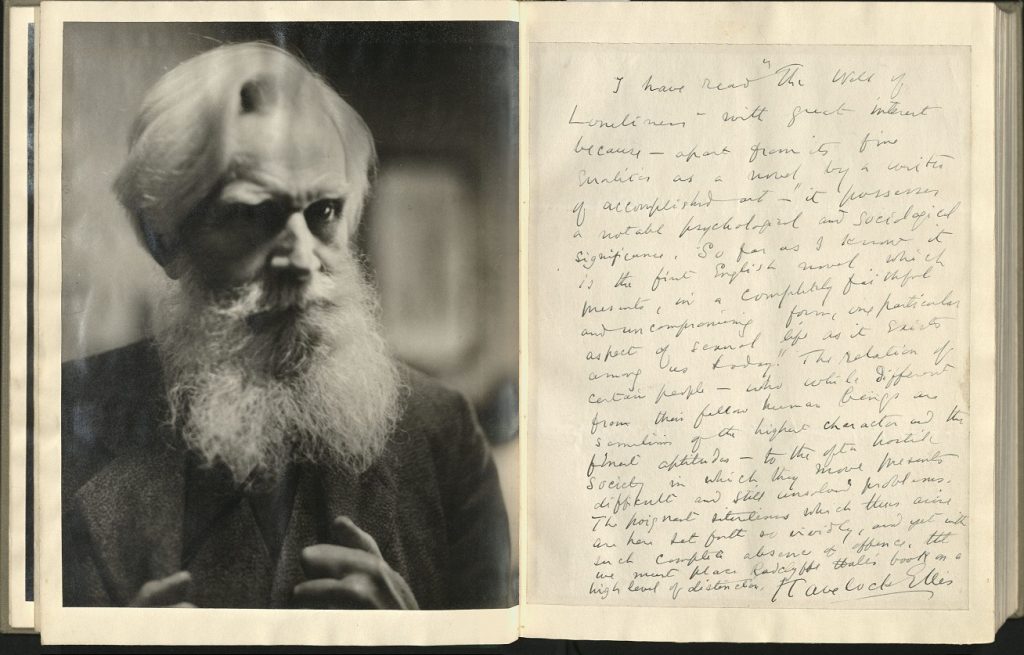

Hall intended her novel as both a work of art and a means of gaining sympathy and recognition for same-sex love. In his introductory comment, Havelock Ellis writes,

So far as I know, it is the first English novel which presents, in a completely faithful and uncompromising form, one particular aspect of sexual life as it exists among us to-day. The relation of certain people—who, while different from their fellow human beings, are sometimes of the highest character and finest aptitudes—to the often hostile society in which they move presents difficult and still unsolved problems. The poignant situations which thus arise here are set forth so vividly, and yet with such complete absence of offence, that we must place Radclyffe Hall’s book on a high level of distinction.

Havelock Ellis’s prefatory “commentary,” with photograph of Ellis in the first volume of a typescript for Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness. England, approximately 1928. Call #: MS D45. Click image to enlarge.

Ellis’s careful allusion to the “complete absence of offense,” however, did not convince all readers. Though The Well of Loneliness contains no sexually explicit scenes, its subject matter and its insistence on the humanity of its queer characters inspired controversy upon its release in 1928. James Douglas, the editor of the tabloid newspaper the Sunday Express, published an article in which he famously and bombastically asserted that he “would rather give a healthy boy or a healthy girl a phial of prussic acid” than Radclyffe Hall’s novel. “Poison kills the body but moral poison kills the soul,” Douglas wrote as he called upon the government to take action to suppress the book. At the urging of England’s Home Secretary, the novel’s publisher, Jonathan Cape, withdrew it from sale. However, Cape also arranged to have the printing molds sent to the Pegasus Press in Paris, with the plan of importing copies. When those copies of the novel were brought back into the UK from France, both Cape and the London bookseller involved, Leonard Hill, were charged under the Obscene Publications Act of 1857. Following a trial, Chief Magistrate Chartres Biron ordered copies of the novel be destroyed, and The Well of Loneliness was not republished in the United Kingdom until 1949.

Across the ocean, the novel fared better. John Sumner of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice lodged a complaint against the American publisher of The Well of Loneliness, Covici-Friede. But ultimately, attorney Morris L. Ernst succeeded in defending Friede against the charge of possessing and selling an obscene book. A victory edition of the novel was released in the U. S., and the controversy that had surrounded it fueled its sales.

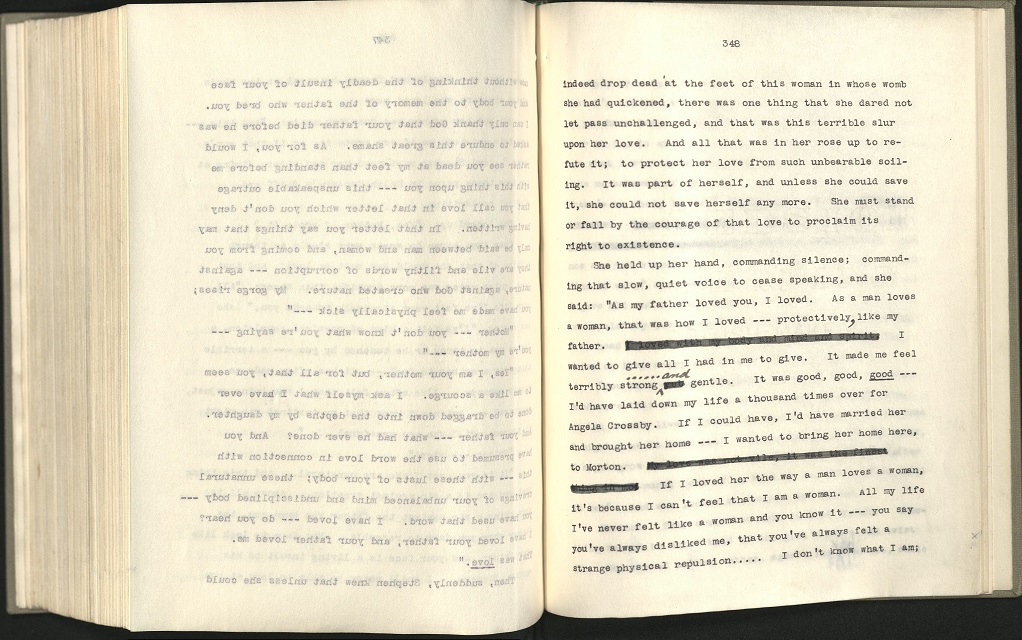

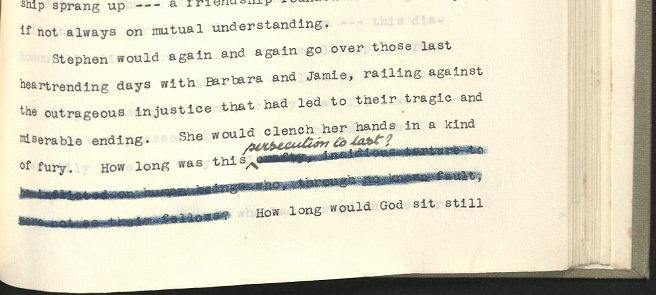

The corrected typescript at Spencer Research Library gives insight into Radclyffe Hall’s process in writing and revising the novel, and it includes emendations in at least two hands. Though some of the deletions remain difficult to read, others can be seen through the black ink and blue crayon used in the editing process (click on the images below to enlarge them). For example, in a scene in which Stephen and her mother argue over the disclosure of young Stephen’s love for the married Angela Crossby, we see that Hall has edited down some of Stephen’s more vocal justifications of her love.

Deletions on p. 348 of a typescript for Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness. England, approximately 1928. Call #: MS D45. Click image to enlarge.

The blacked out lines in the passage above read “I loved with my body and mind and spirit” and “My love was not vile, it was the finest thing in me.” The succeeding lines, which Hall leaves untouched, suggest how the author’s depiction of Stephen’s “inversion” is inflected with elements of what we now call transgender identity. Stephen explains to her mother, “If I loved her the way a man loves a woman, it’s because I can’t feel that I am a woman. All my life I’ve never felt a woman and you know it —.“

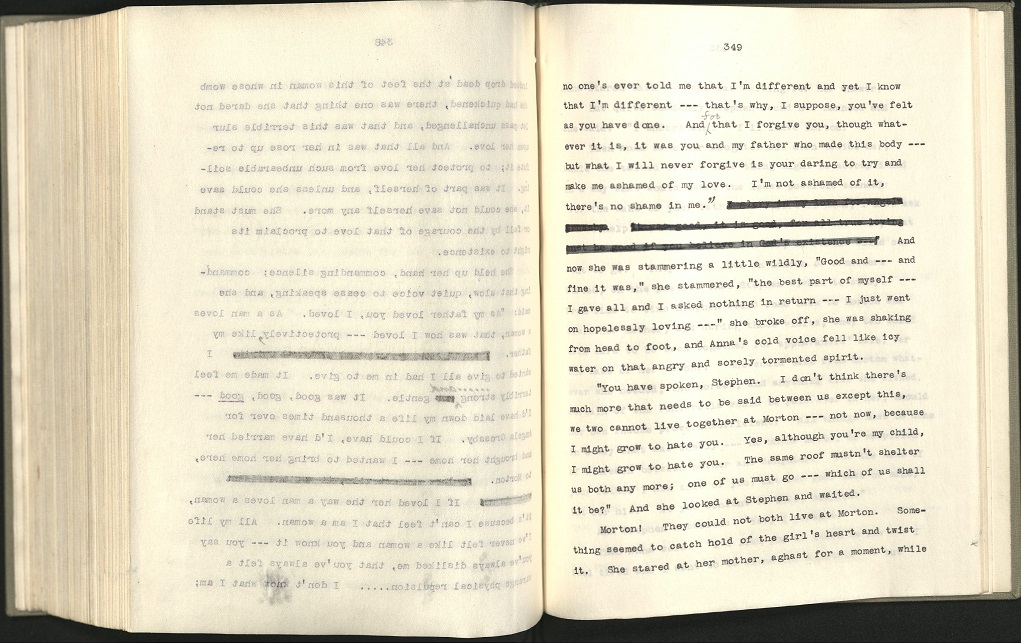

On the following page, Hall also deletes a line in which Stephen invokes God in explaining her love. “I’m not ashamed of it, there’s no shame in me,” Stephen declares, and then the deleted text continues, “I glory in my love for Angela Crossby. It was good, it is good, for all true loving must be good if you believe in God’s existence —.“

Additional deletions on p. 349 of the typescript for Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness. England, approximately 1928. Call #: MS D45. Click image to enlarge.

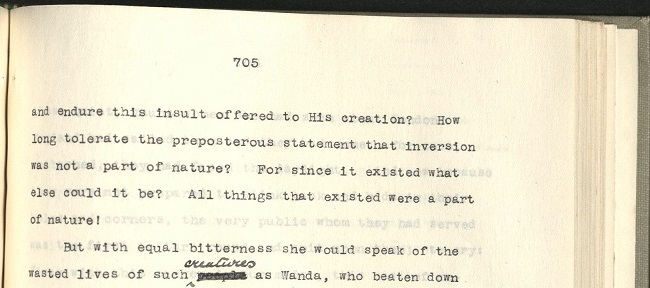

The idea that same-sex love is a part of God’s creation recurs throughout the novel, as does Stephen’s anguish at being persecuted by society for it nevertheless. Following the tragic deaths of Stephen’s two friends, Barbara and Jamie, Hall writes of Stephen, “She would clench her hands in a kind of fury. How long was this persecution to last? How long would God sit still and endure this insult offered to His creation? How long tolerate the preposterous statement that inversion was not a part of nature? For since it existed what else could it be? All things that existed were a part of nature!”

How long was this persecution to last? Details from p. 704-705 of a typescript for Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness. England, approximately 1928. Call #: MS D45. Click images to enlarge.

2018 marks ninety years since The Well of Loneliness was first published. In spite of its suppression for two decades in the UK and the attempt to suppress it in the US, readers and scholars continue to analyze and respond to Radclyffe Hall’s novel. We invite you to delve further into its history by exploring the “special” typescript copy, with emendations, held at the Spencer Research Library. Researchers can then compare this copy to other drafts available in the collection of papers for Hall and her partner Una Troubridge at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas.

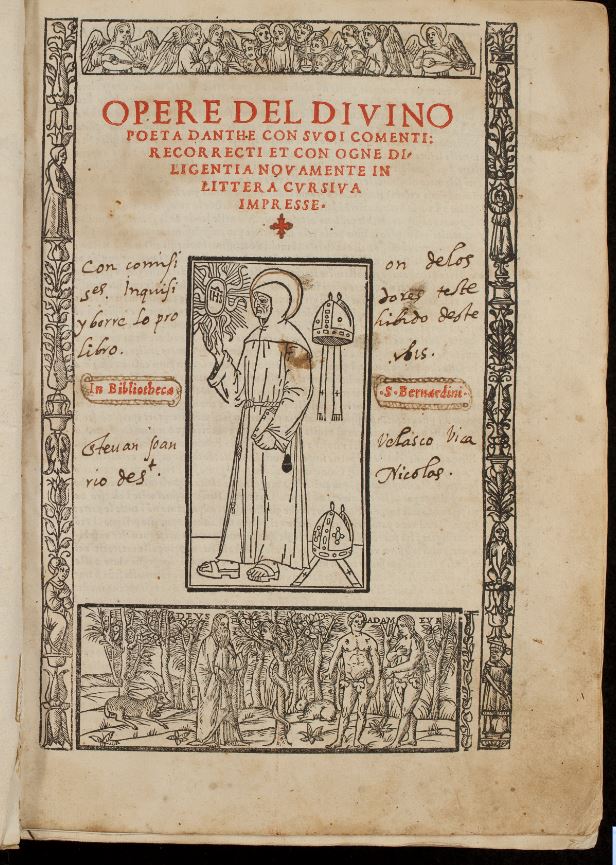

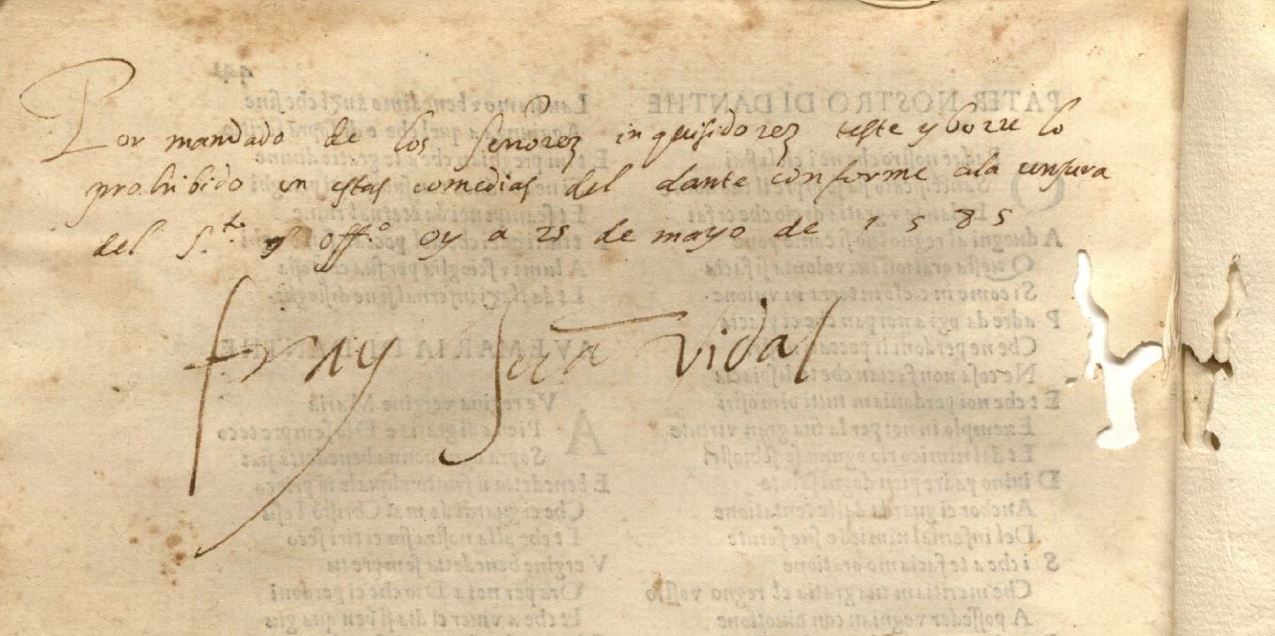

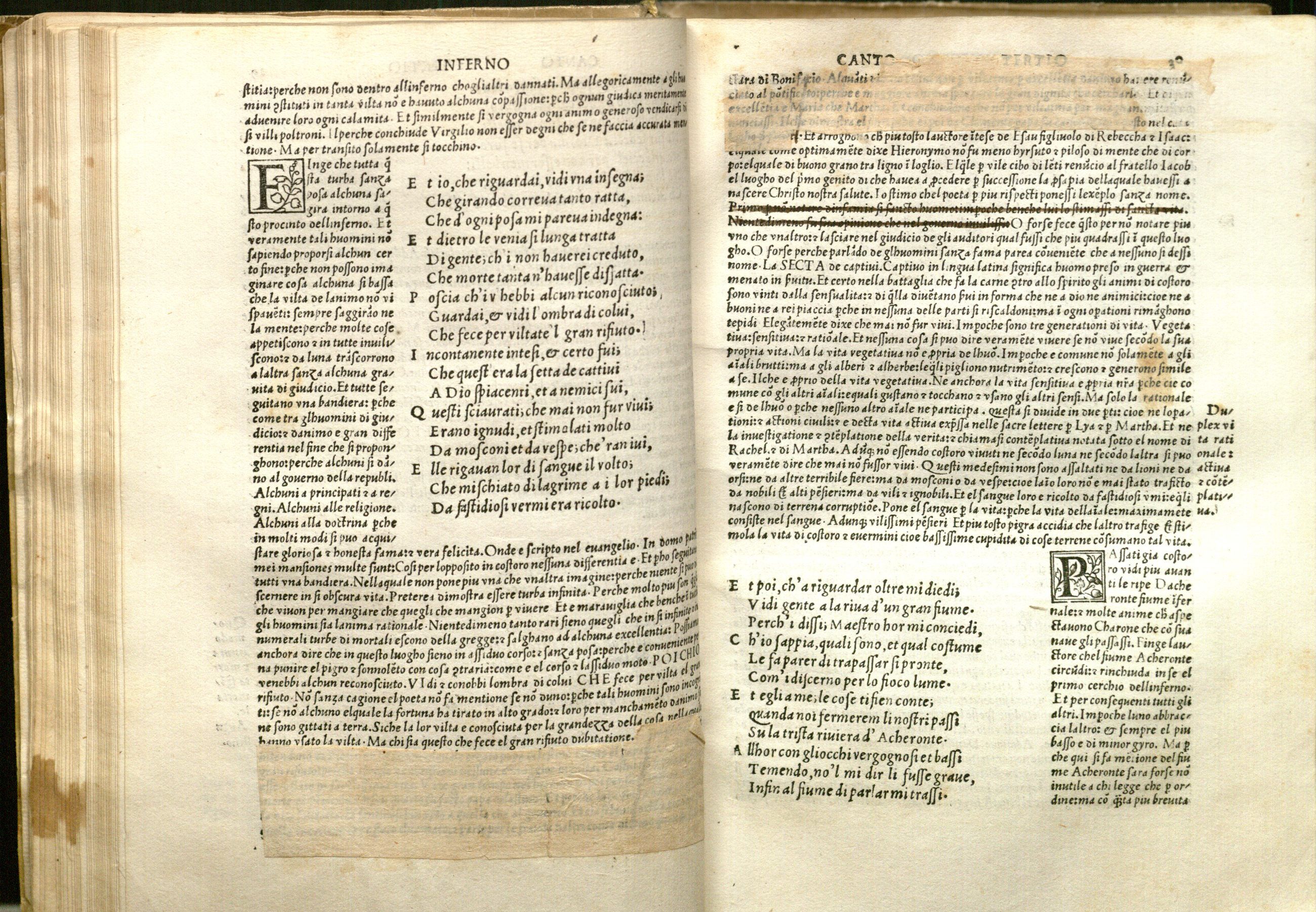

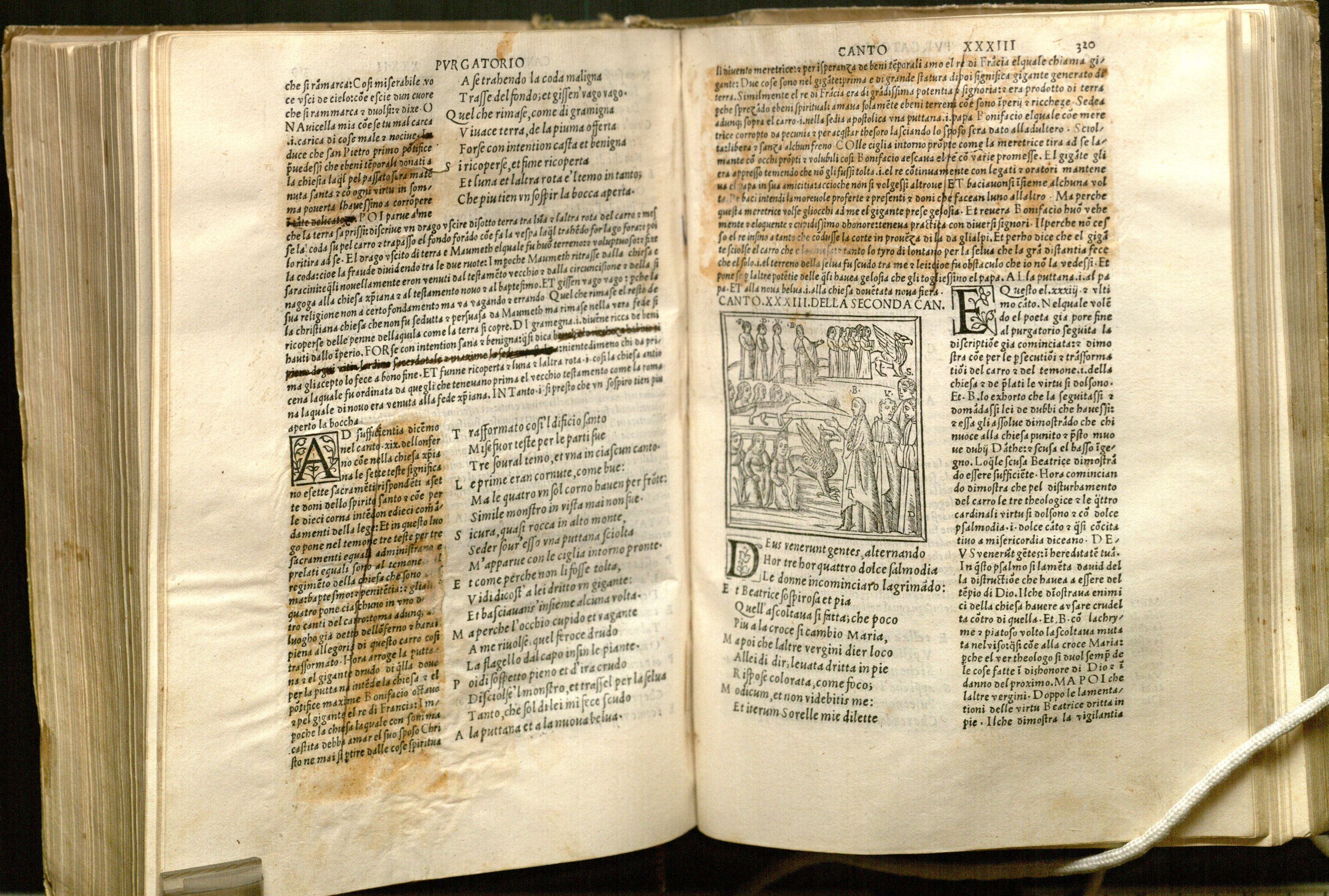

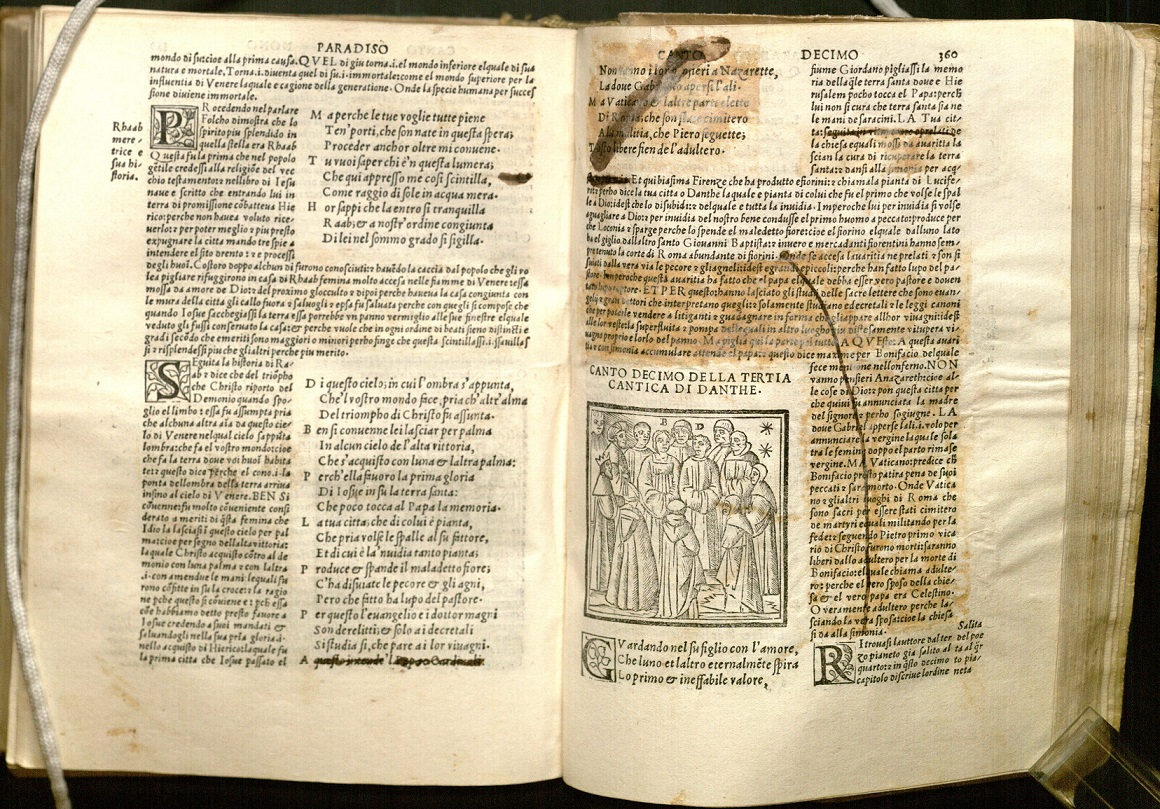

Interested in more material related to banned books? Take a peek at last year’s banned books week post on Spencer Library’s copy of a 1512 edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy that was expurgated at the behest of the Inquisition in Spain. Curious about more contemporary instances of censorship and challenges to books? Read through the lists of the top 10 most frequently challenged books for each year since 2001.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian