Peggy Hull Deuell: A Conservation Internship

August 15th, 2014As the 2014 Summer Conservation intern, I performed treatment on the University’s collection of Peggy Hull Deuell, America’s first female war correspondent. This part of the Kansas Collection is comprised of a wide variety of materials: newspaper clippings from the 19th-20th centuries, manuscripts dating from 1774, photographs, oversized items such as maps, transparent documents, and scrapbooks.

A significant portion of time was taken to wash and alkalize the very brittle and disheveled collection of newspaper clippings. During the weeks performing treatment, I became very familiar with Peggy’s style of writing; her sassy personality and strength of character were true elements in her journalism. As the only records of her reporting, these newspaper clippings are important testaments to not only her personal struggles, but also to the relationship she had with readers of the numerous newspapers she wrote for (including the El Paso Morning Times, Chicago Tribune, New York Daily News, and Cleveland Plain Dealer).

Though Ms. Hull was born in Bennington, Kansas (in 1889), she was hardly the typical Midwestern girl of the late 19th century. She was independent, intelligent, and very restless. It’s surprising then, that she never graduated high school and was intended to settle down and study pharmacy. This path did not last long; with the family’s subsequent proximity to Fort Riley and its soldier population, and Peggy’s eagerness for change, she soon discovered a new career in the form of journalism. The rest you could say, is history.

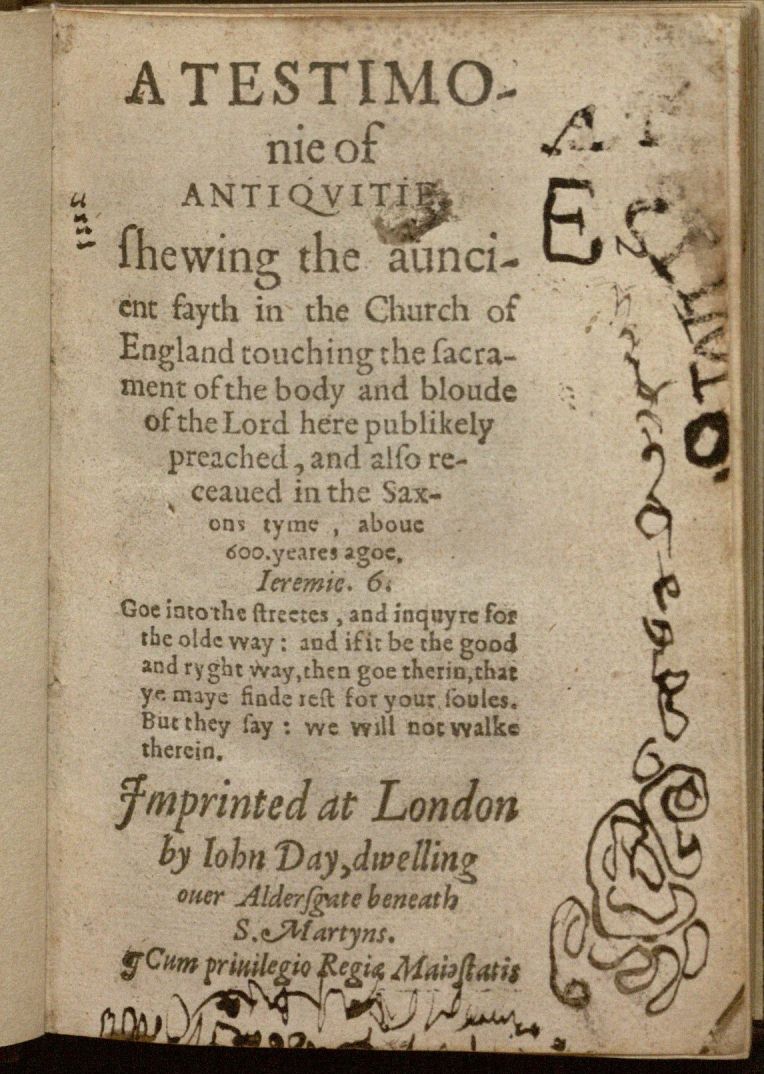

Peggy Hull [Deuell] in WWI uniform, 1917. Kansas Collection, Call Number RH MS 130. Click image to enlarge.

It was a rocky start for Peggy, who struggled to become recognized in an incredibly male-dominated field. In fact, it took Peggy about 10 years and travels all over the world to finally become an accredited war correspondent. Through her journeys across the U.S., to the Mexican border, and to Paris, London, Siberia, and Shanghai, she was teaching people about the war, current events, and even her everyday life. It was Peggy’s determination, unrelenting optimism, and quirkiness that I found most exciting about this collection.

My favorite articles are those that interact with the reader: where you can really get a sense of Peggy, the person behind the journalist. Also quite lovely are the assortment of letters between Peggy and unknown correspondences (or rather, named yet unfamiliar). One such letter was even imprinted with what I believe to be Peggy’s lipstick! The smell was still quite intense, and I could just about imagine Peggy sealing the letter with a kiss (something I imagine she’s done for her three husbands)!

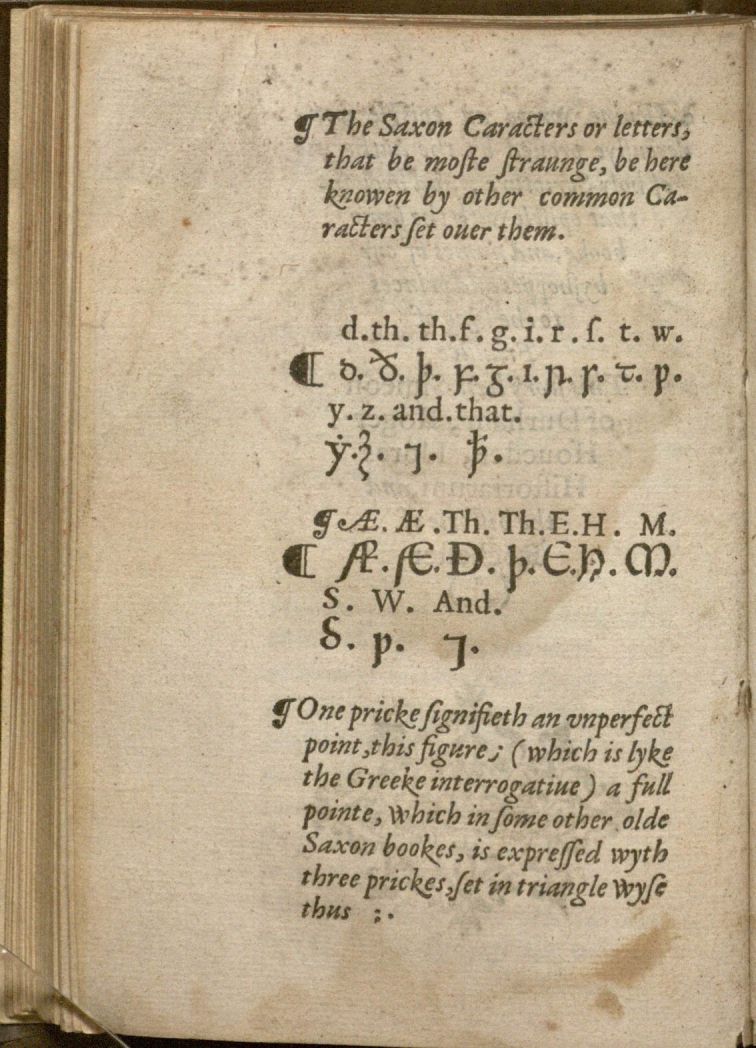

Amusing piece written by Peggy Hull Deuell. Peggy Hull Deuell Collection,

Kansas Collection, Call Number RH MS 130. Click image to enlarge.

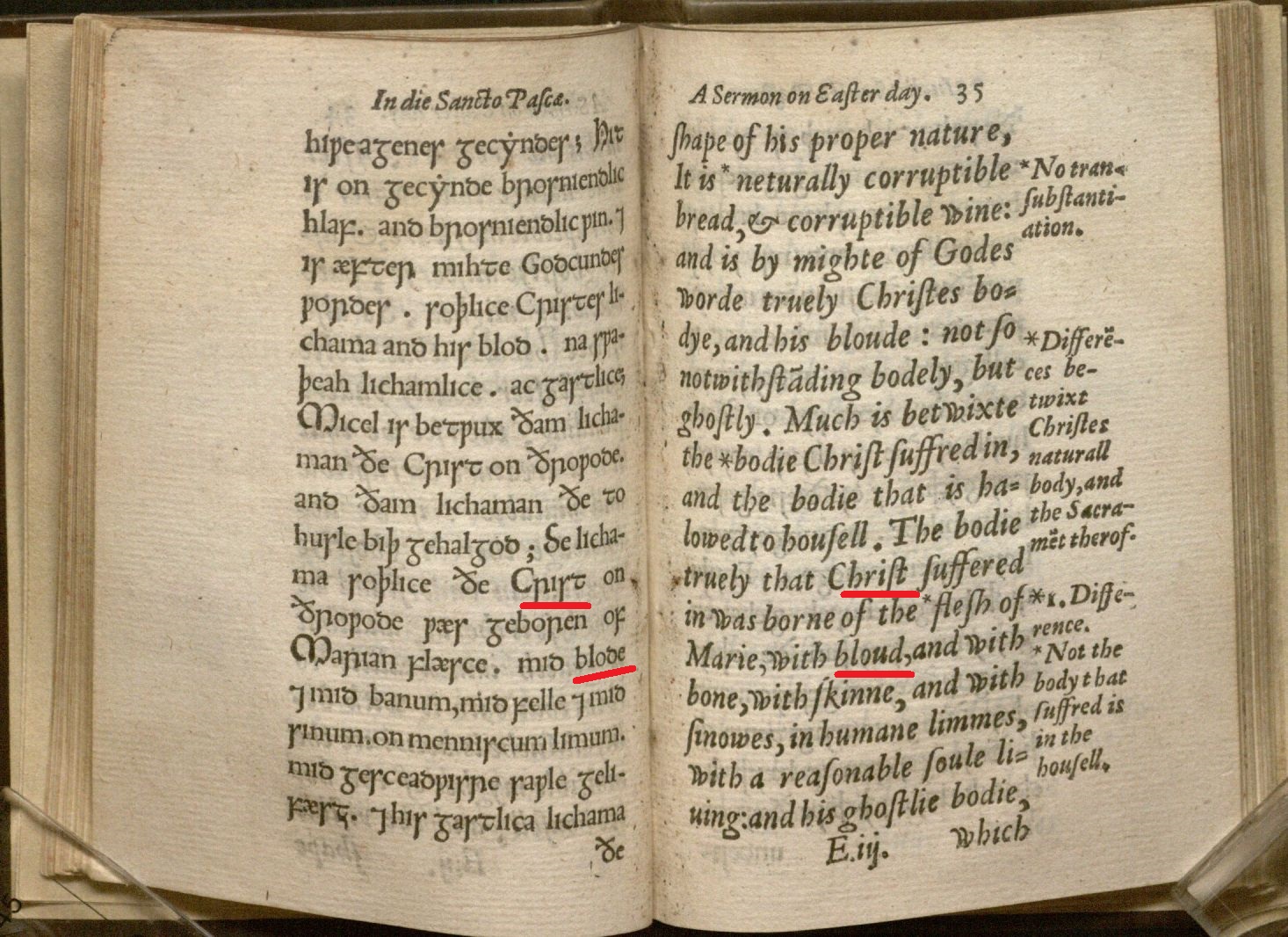

Though the process of washing, repairing, and even reading Peggy’s newspaper clippings was intensive and often very entertaining, my favorite conservation treatment with this collection was of the oversized items. The flexibility of the project allowed me to spend time performing more in-depth treatment on a small selection of posters. One of the pieces is an article Peggy wrote about news in Siberia; the document had been pasted to a canvas, which was subsequently painted on the reverse. Over time, the newsprint became very brittle and discolored from both the adhesive and acidity of the material, resulting in a badly damaged article. To treat this object, I first removed dirt from the surface of the paper and then immersed it in a tray of water. After about 5 minutes of soaking in the bath, I was able to carefully separate the newsprint from the canvas. As suspected, the newsprint was extremely fragile and had broken into many pieces over its lifetime. The canvas backing was discarded and the article was rewashed and alkalized in a separate bath to reduce its acidity. Then, after being dried and pressed flat, I undertook the tricky process of lining the article; in other words, I adhered a thin Japanese tissue to the back of the object in order to add strength and allow for the reattachment of its many pieces. Only when the pieces were reunited could I begin the process of toning papers and filling in missing areas to the overall document. Once treatment was completed, the article could be safely handled and more easily read.

Before, during, and after treatment of a clipping from the Peggy Hull Deuell Collection.

Kansas Collection, Call Number RH MS 130. Click images to enlarge.

Treatment of the Peggy Hull Deuell Collection was very successful, and I had a wonderful summer working between the Watson and Spencer Research Libraries. Peggy’s collection is also one of the many fantastic features that facilitates our study of war history, and in particular, helps to commemorate the 100th anniversary of World War I. I do think that Peggy would be quite proud of her collection as well!

For further reading about Peggy and her adventures, I highly recommend The Wars of Peggy Hull by Wilda M. Smith and Eleanor A. Bogart, a book written with the consultation of this very collection!

Amber Van Wychen

2014 Summer Conservation Intern, Stannard Conservation Lab