From the Stacks: Sword and Blossom Poems

October 27th, 2012Public Services Student Assistant Eleni Roussopoulos writes of a favorite discovery from the stacks.

One day while re-shelving books in Spencer’s Special Collections book stacks my attention was caught by a navy-blue box on a lower shelf. Unable to walk away without knowing the contents of the box, I carefully opened it. Inside this box lives a three-volume set of hand-made books titled Sword and Blossom Poems from the Japanese Done into English Verse by Shotaro Kimura and Charlotte M.A. Peake, [1908 – 1910].

The three volumes of Sword and Blossom Poems from the Japanese / done into English verse by Shotaro

Kimura & Charlotte M.A. Peake ; illustrated by Japanese artists. Tokyo: T. Hasegawa, Meiji 41 [1908-1910].

Call Number B3136. Click image to enlarge.

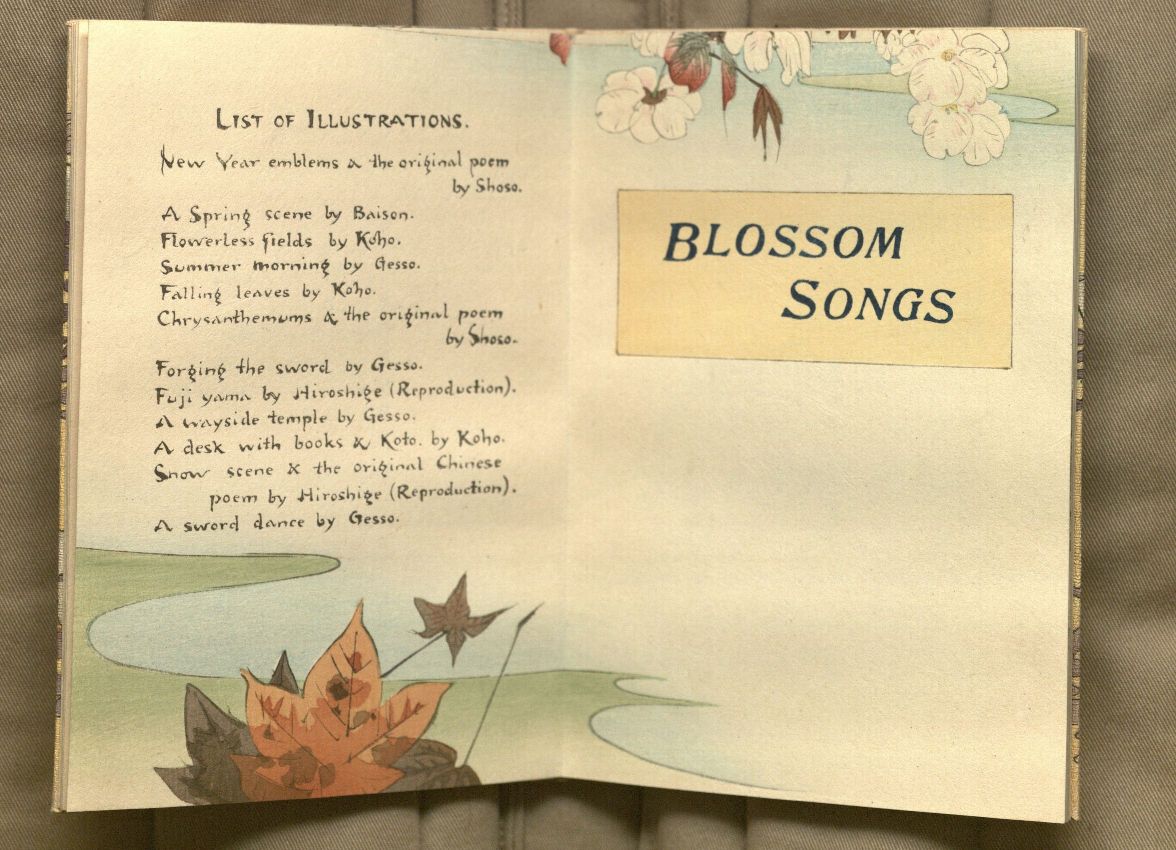

Each volume features both “Sword” and “Blossom” poems, where the text is accompanied by woodcuts from various Japanese artists and is printed by woodblock (rather than by moveable type). The “Blossom Songs” are tanka (short unrhymed poems) translated from the Kokinshū anthology of Japanese poems compiled circa 905 C.E.

“Blossom Songs” half title, with list of illustrations for the second volume;

“Snow,” with a reproduction of a Hiroshige snow scene, and “Misere” and “Maple Leaves,”

with illustration by Kohō, from the “Blossom Songs” section of the first volume of Sword and

Blossom Poems from the Japanese. Call Number B3136. Click images to enlarge.

The “Sword Songs” were composed in the Chinese style by various Japanese authors. In the introduction, the editor informs the reader that the “the spirit that breathes through [the sword songs] is the spirit that has animated the warriors of Japan from the earliest days.”

The “Sword Songs” section title page and “A Sword Dance of the Satsuma Clan, ” both with illustrations by Gesso, from

volume two of Sword and Blossom Poems from the Japanese. Call Number B3136. Click images to enlarge.

These surprisingly sturdy hand-made books, with crepe-paper covered boards, were published in Tokyo by T. Hasegawa at the beginning of the twentieth century. Gorgeous and fascinating to look at, these short books offer an excellent example of the now-vanishing art of Japanese wood-block printing.

Eleni Roussopolous

Public Services Student Assistant

![Plate from James Petiver's Gazophylacii Naturae & Artis in qua animalia [...] Plate from James Petiver's Gazophylacii Naturae & Artis in qua animalia [...]](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/EllisAves_E116_item2.jpg)