Counterparts and Crossed-out Prohibitions against Fornication; Or, Adventures in Indentures

September 26th, 2013Anyone who has ever tried to read the fine print on a lease or an online click-through user agreement knows that contracts can at times be rather stultifying documents. Even in the early modern period, contracts used formulaic language that could be dry and impenetrable enough to put off all but the most dedicated reader. However the physical formats of these documents can be quite fascinating, especially to modern eyes.

An indenture is a legal contract between two or more parties which reflects an obligation or covenant between those parties. Common types of indentures include leases, bonds, apprenticeship agreements, and marriage agreements, to name a few.

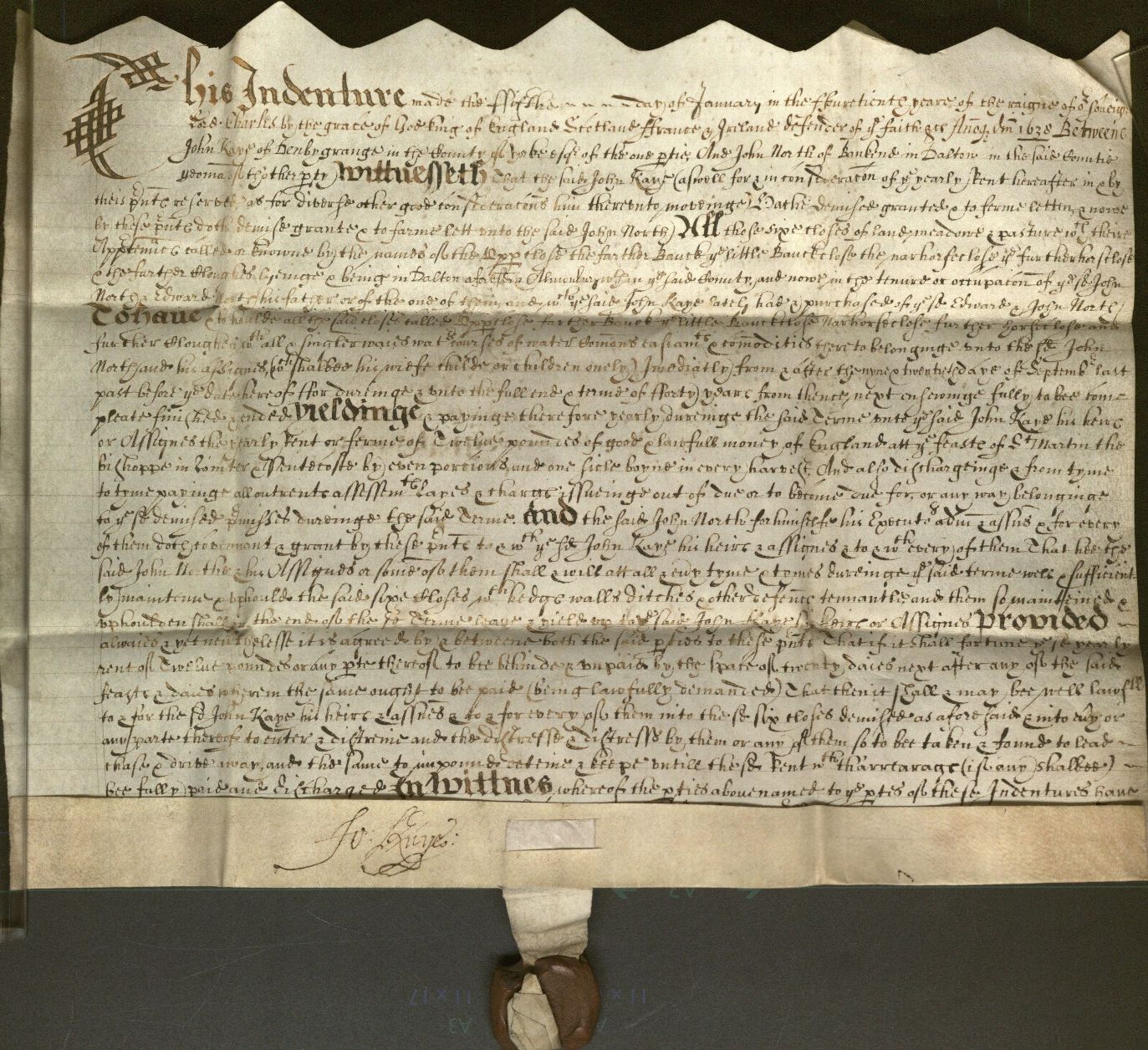

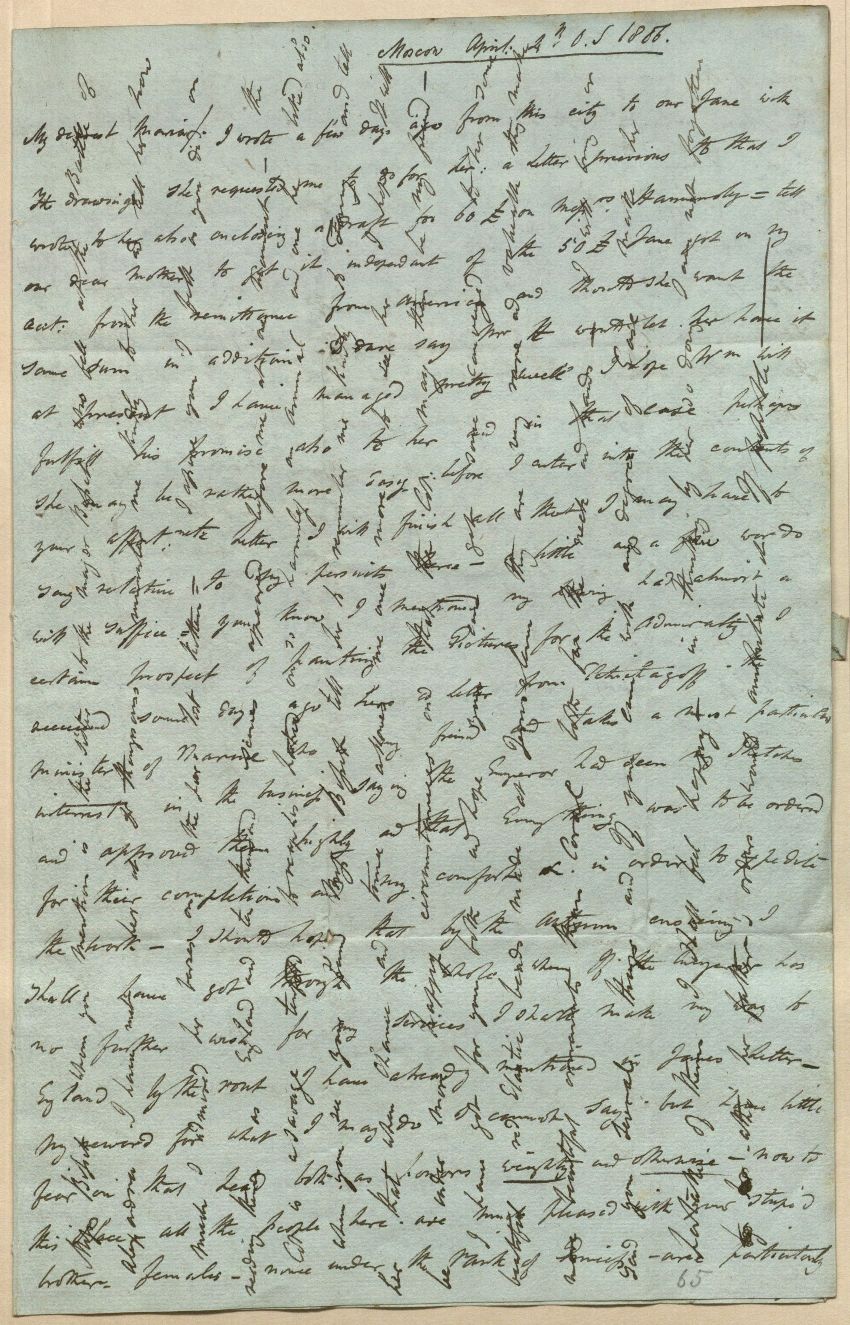

Lease indenture between John Kaye of Denby Grange and lessee John North of Bankend for land in Almondbury in Yorkshire, 1639. Kaye Family Estate Papers. Call Number: MS 240B: 111. Click image to enlarge.

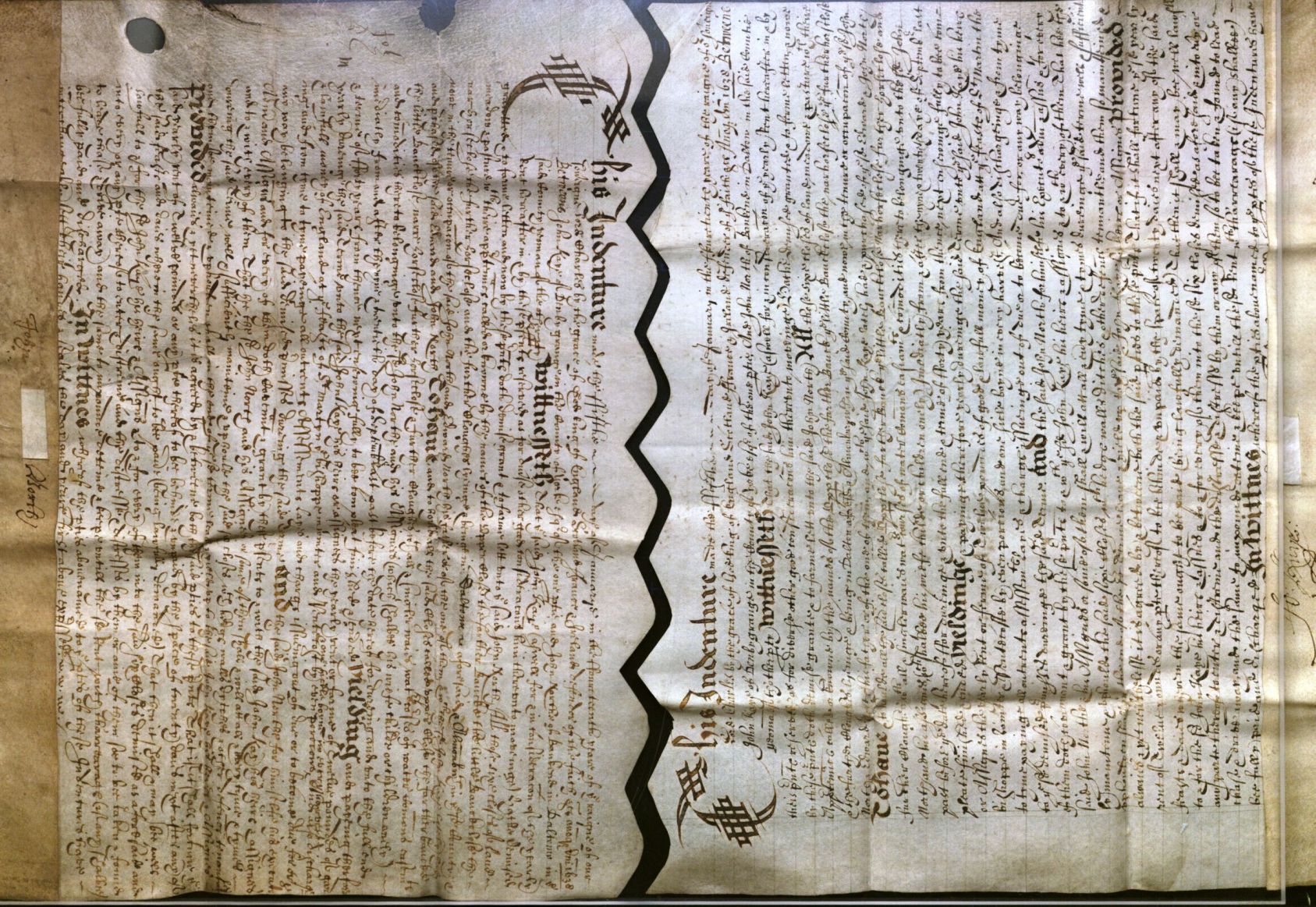

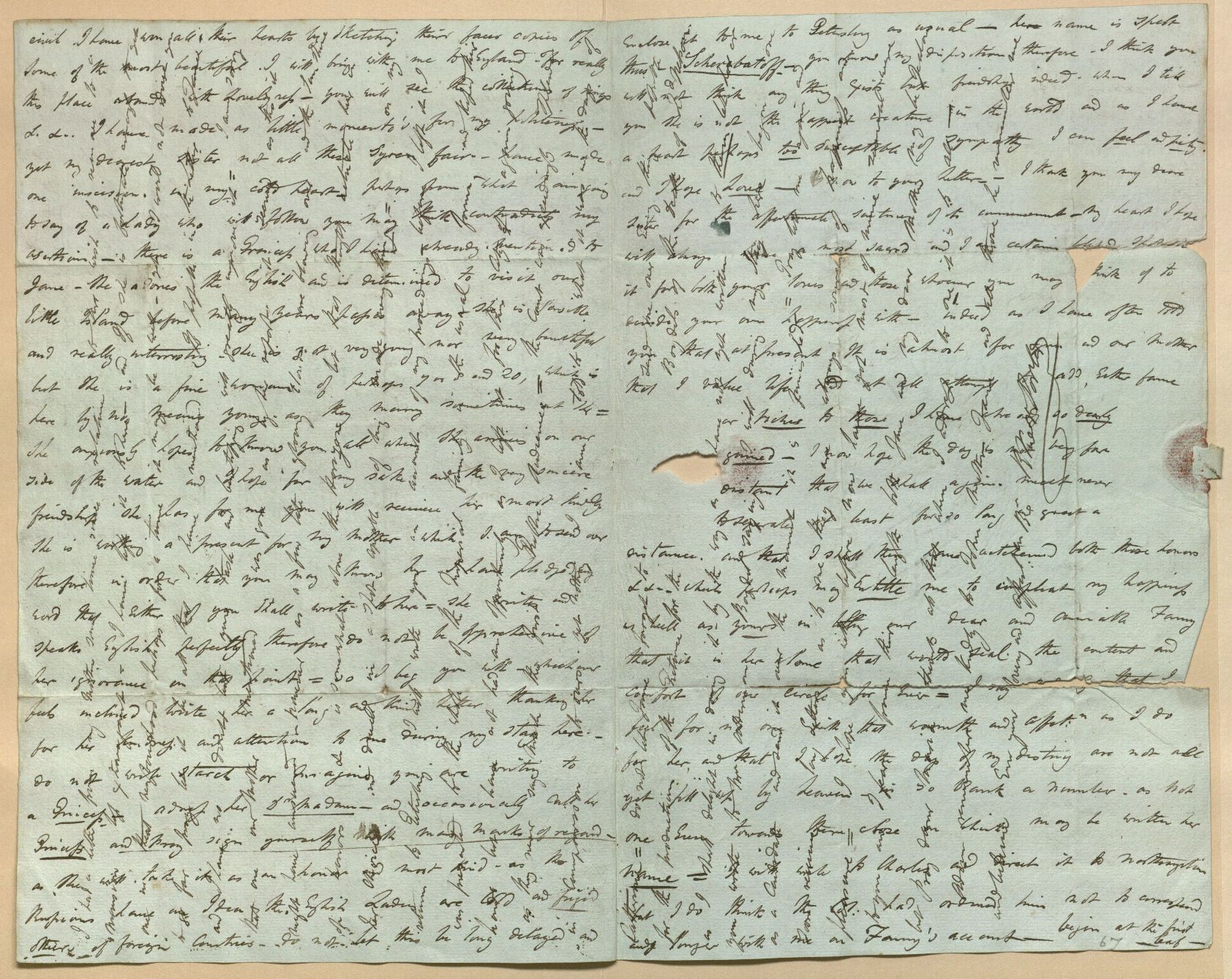

The term “indenture” originally referred to the physical form of this contract. As a security and authentication measure, two or more copies of the deed would be written on the same piece of parchment (animal skin), usually head to head (i.e. with top of one copy facing the top of the other) and then the parchment would be cut in two in a wavy or zigzag pattern to produce the two copies of the contract. The authenticity of the indenture could then be validated by reuniting and matching its edges to those of its “counterpart.”

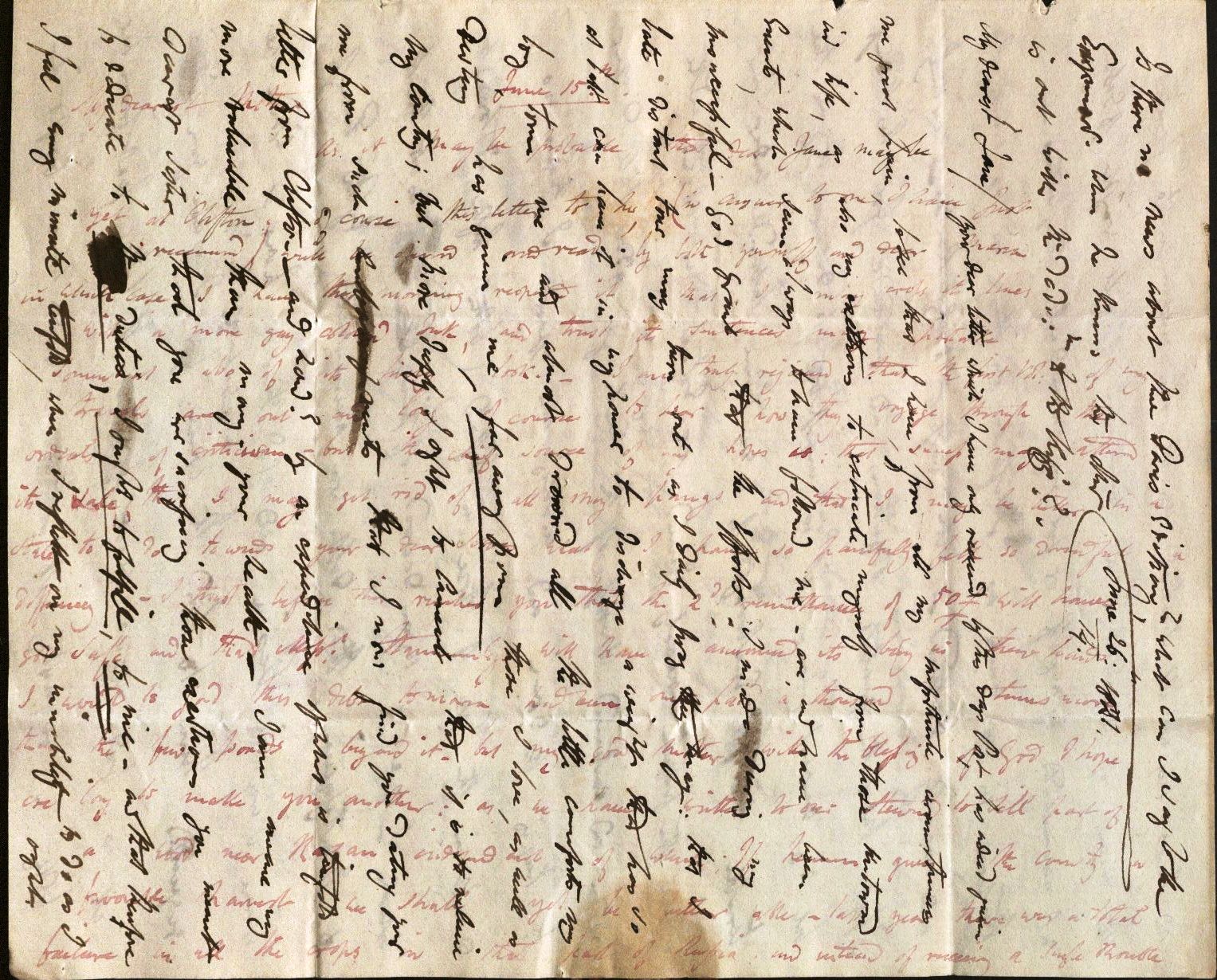

Indenture and counterpart matched along their scalloped edges. Lease between John Kaye, of Denby Grange and lessee John North of Bankend for land in Almondbury in Yorkshire, 1639. Kaye Family Estate Papers. Call Number: MS 240B: 110-111. Click image to enlarge.

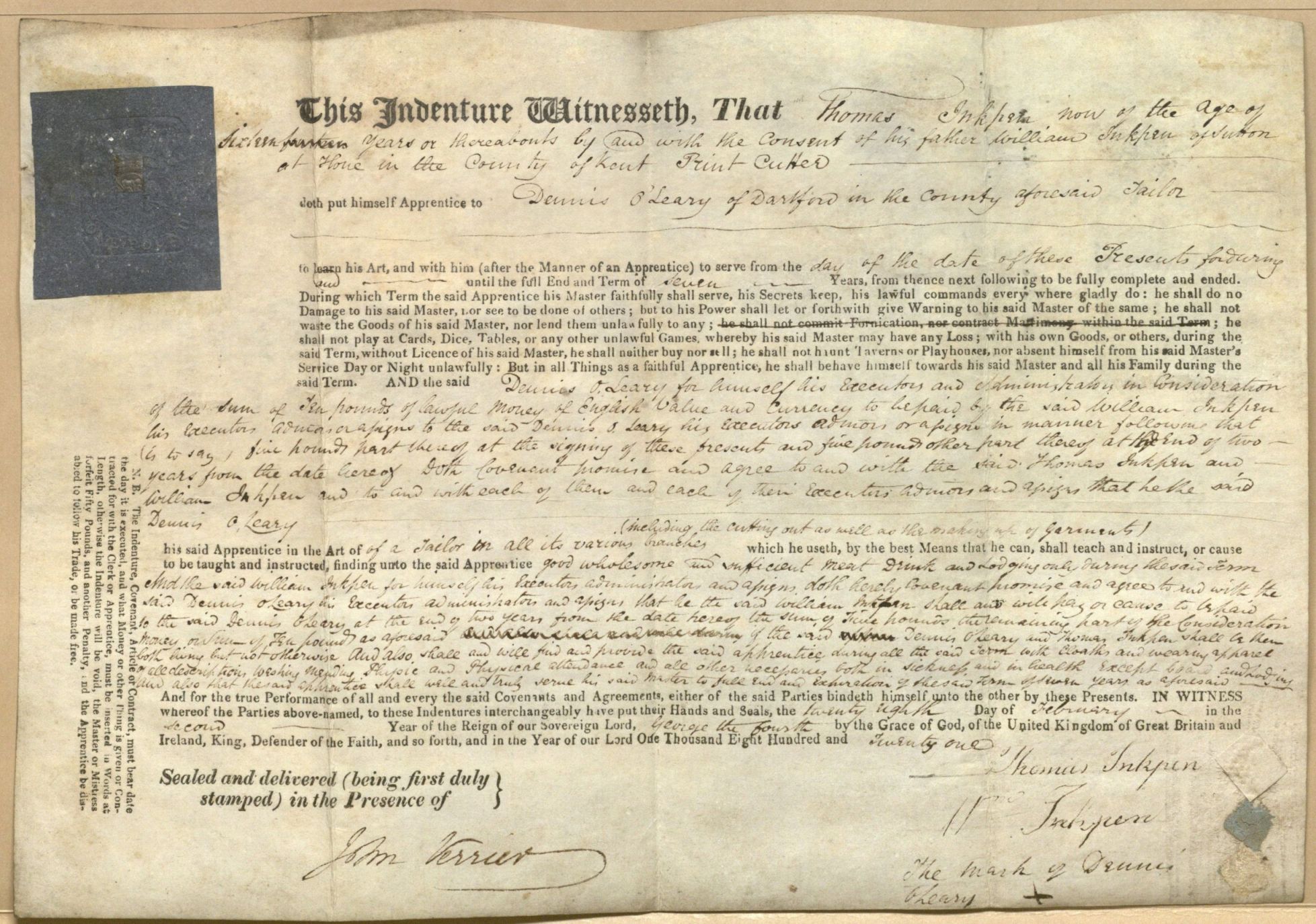

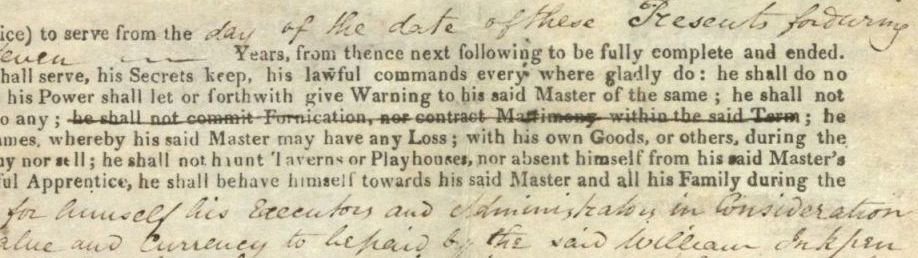

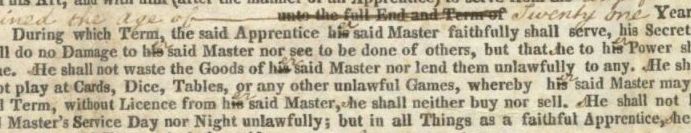

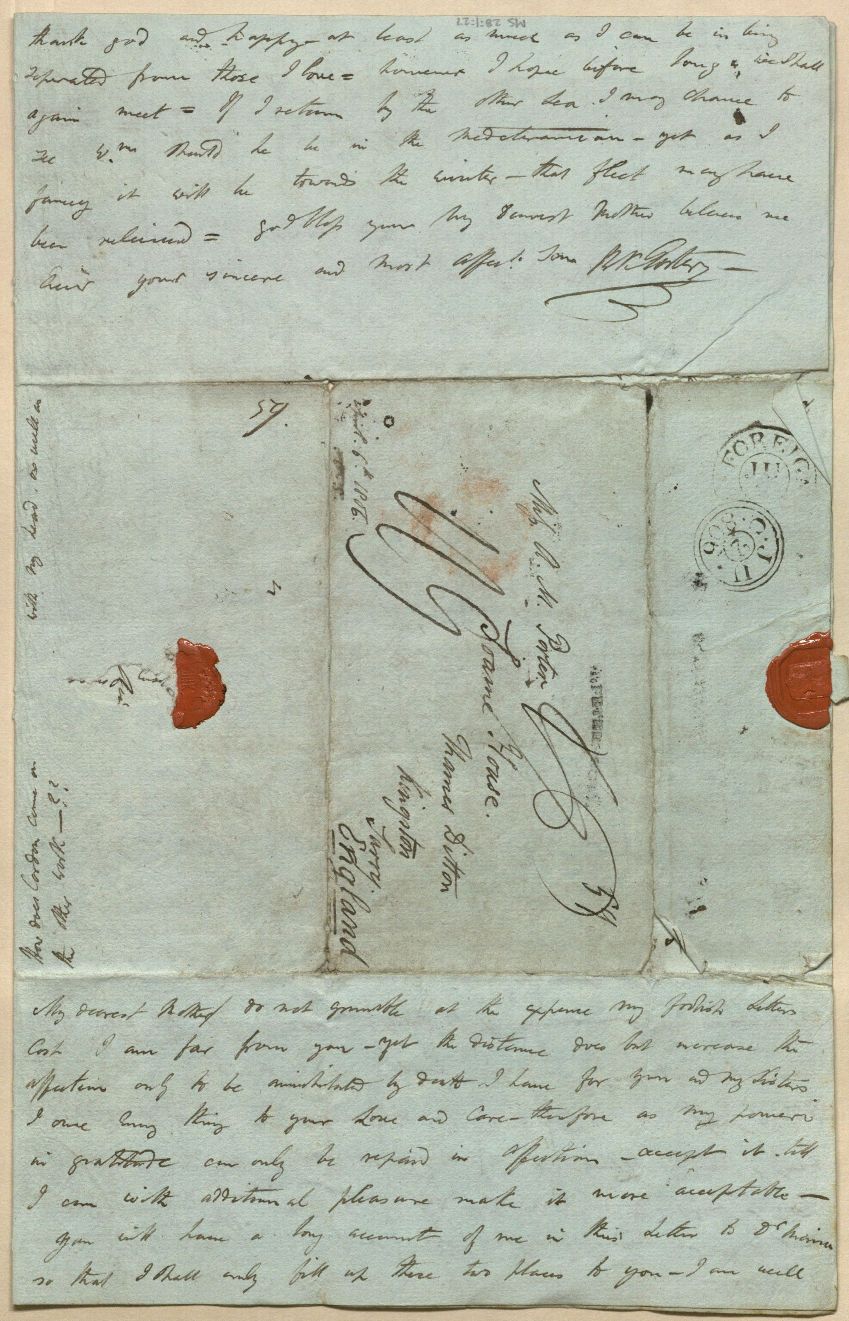

In later years, it was not uncommon to see printed indentures–essentially “forms” in which the formulaic parts are printed and the particulars were added in manuscript. Spencer’s English Historical Documents collection includes many printed apprenticeship indentures from the 19th century. It is fascinating to see how the printed forms (still on parchment, mind you!) can be tailored to cover the specific details of a given agreement. A common stipulation of such agreements was that the apprentice agree not to partake in a variety of activities that might negatively impact his Master or divert the apprentice’s attentions (“he shall not play at Cards, Dice, Tables, or any other unlawful Games…” nor “haunt Taverns or Playhouses, nor absent himself from his said Master’s Service Day or Night”). In the case of the apprenticeship indenture of young Thomas Inkpen (who, based on his name, clearly missed his calling as a scrivener) to the tailor Dennis O’Leary (below), we can see that the prohibition against fornication or marriage has been struck out, leaving him free to marry during his seven-year term of apprenticeship. Indeed, this stipulation may have been omitted because Inkpen was already married or engaged. (It’s also interesting to note that Inkpen signs his own name, but O’Leary, the tailor to whom he will be apprenticed, signs only with his “mark.”)

Apprenticeship indenture of Thomas Inkpen to tailor Dennis O’Leary. February 28, 1821. English Historical Documents Collection. Call Number: MS 239:3818. Click images to enlarge.

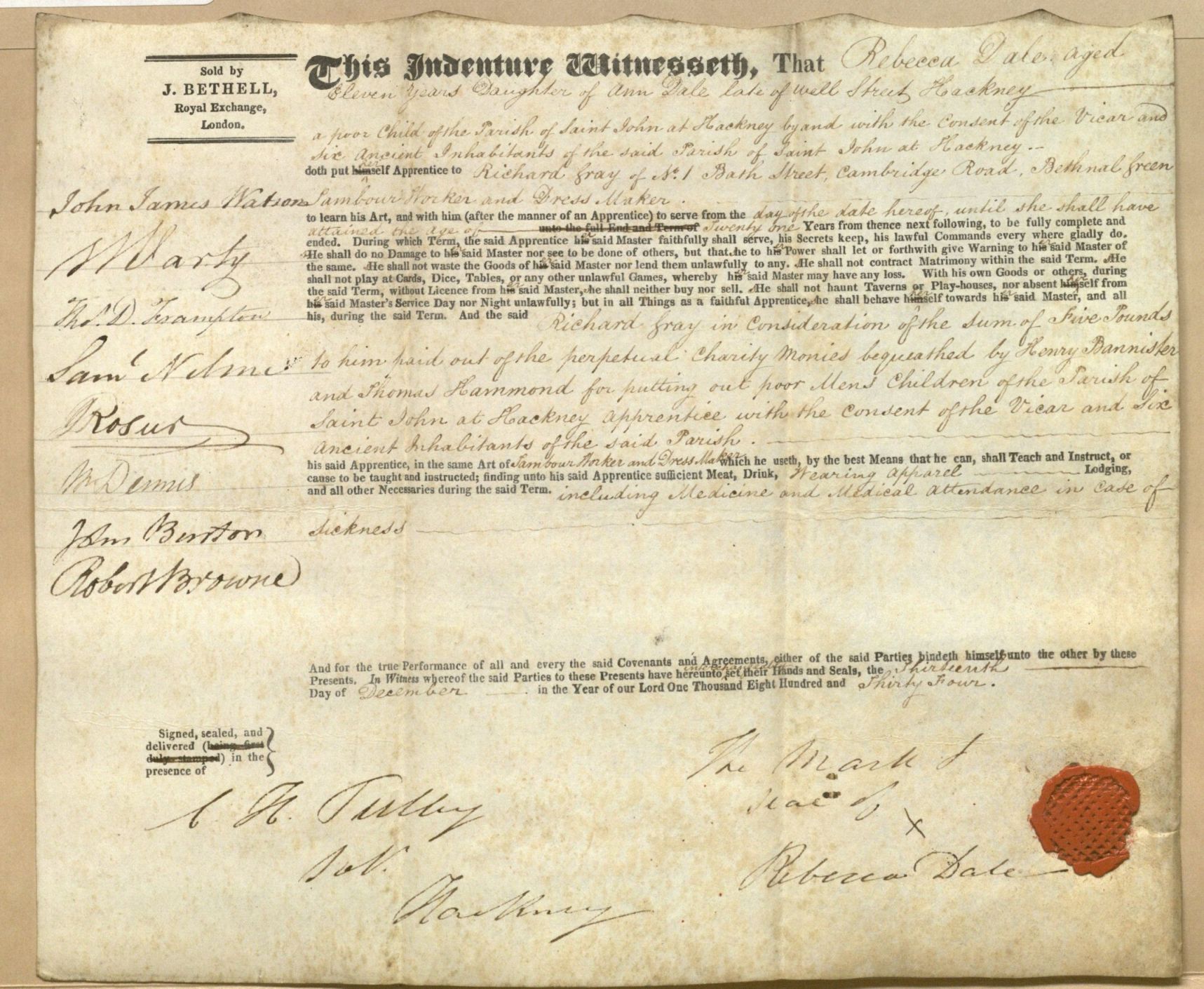

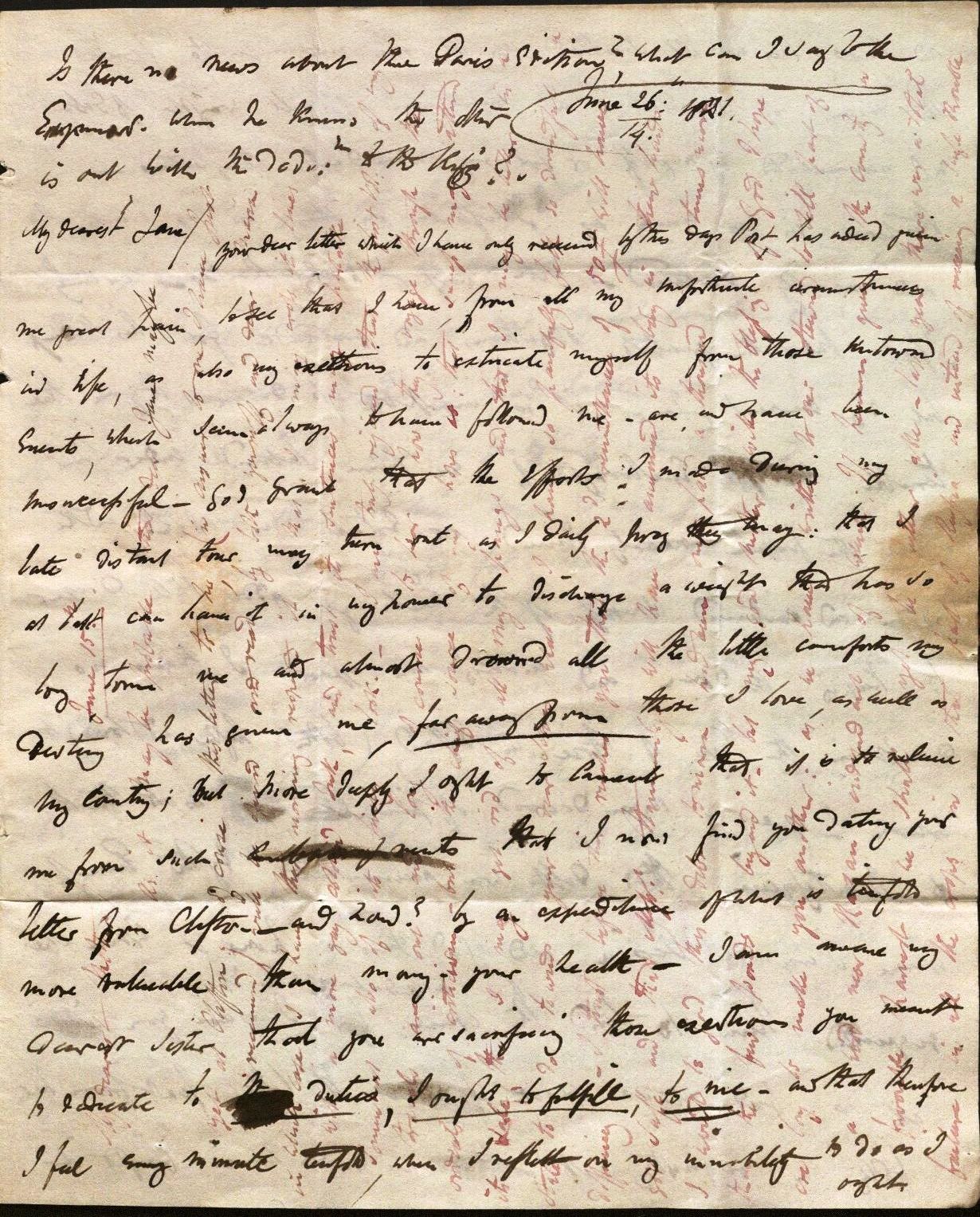

Female apprentices might also occasion the alteration of the printed part of the indenture, which most often assumed a male apprentice. In the 1834 indenture of eleven year-old Rebecca Dale to Richard Gray, a Tambour worker and Dressmaker, male pronouns on the printed part of the form have been crossed-out and replaced with female ones.

He to She and His to Her: Apprenticeship indenture for Rebecca Dale to Richard Gray, Tambour worker and Dress maker . December 13, 1834. English Historical Documents. Call Number: MS 239:3823. Click images to enlarge.

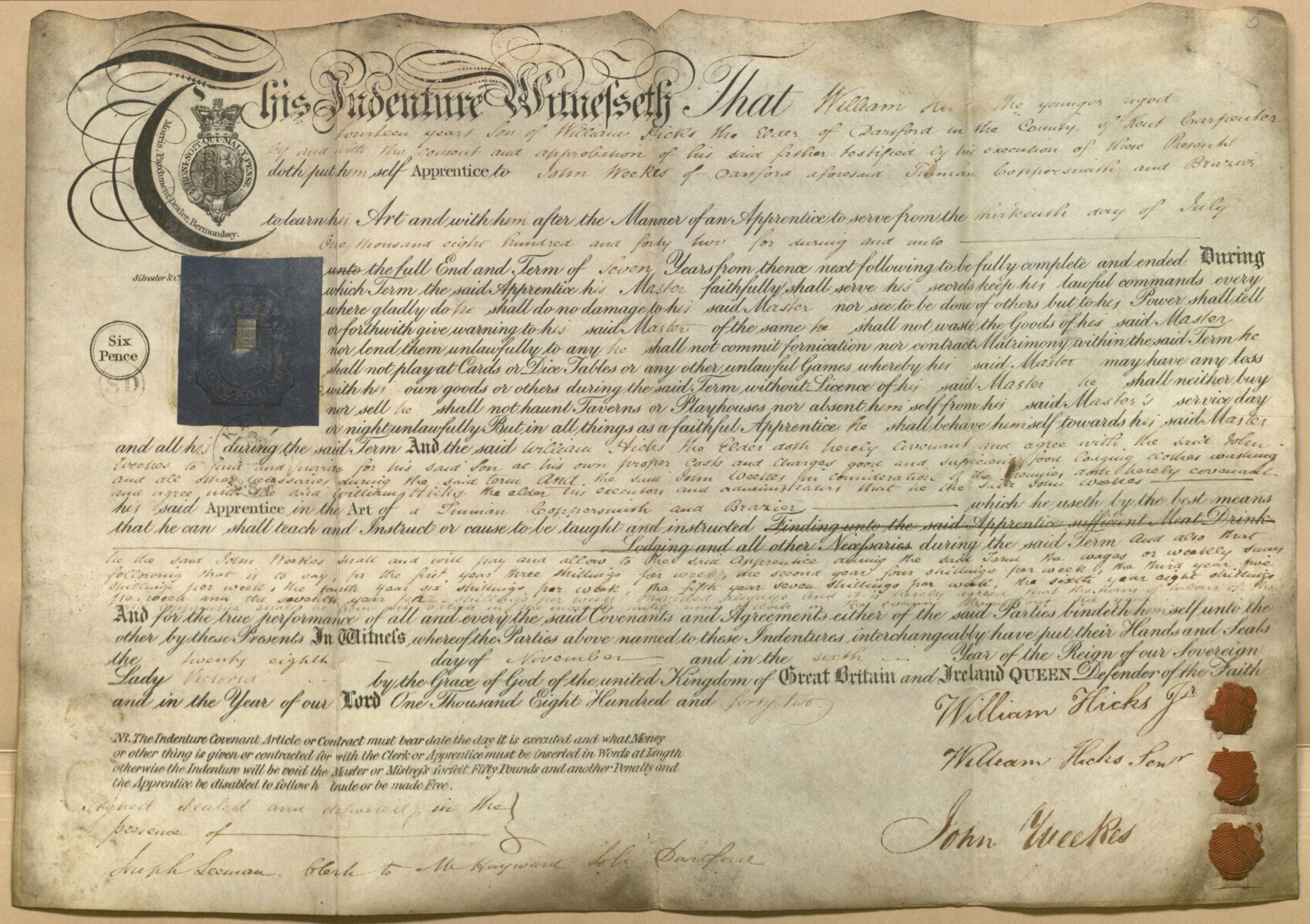

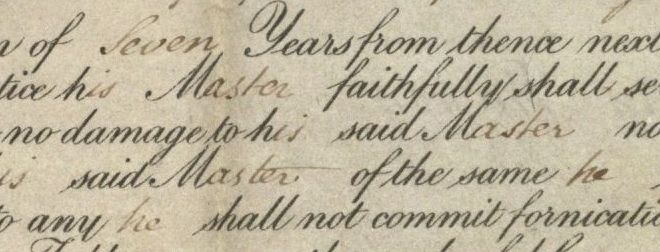

Female apprentices soon became common enough that some printers left blanks on their forms to allow for the possibility. Though the following 1842 indenture is for a boy, William Hicks, to be apprenticed to John Weekes, a Tinman, Coppersmith, and Brazier, the blanks permit it to accommodate a female apprentice with equal ease and even allow for a “Mistress” rather than a “Master.”

Fill in the blank: M(aster) or M(istress)? Indenture for William Hicks, Jr. to be apprenticed to John Weekes, Tinman, Coppersmith, and Brazier. November 28, 1842. English Historical Documents Collection. Call Number: MS 239: 3787.

Spencer’s English Historical Documents collection, comprising over 7000 English deeds and manorial, estate, probate and family documents dating roughly from 1200 to 1900, offers a rich resource for investigating the changing face of the indenture. It also offers insight into two prominent English families, the Kayes of Yorkshire, and the North Family, whose illustrious members include Frederick North, Prime Minister of Great Britain during the American War of Independence. An online finding aid is currently in progress, but in the interim we encourage interested researchers to contact us with their queries.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian

[With special thanks to Mary Ann Baker, processing archivist for the English Historical Documents collection, for locating and identifying the counterparts referred to in this post.]