Manuscript of the Month: From the Library of the Charterhouse of St Barbara in Cologne

June 30th, 2021N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

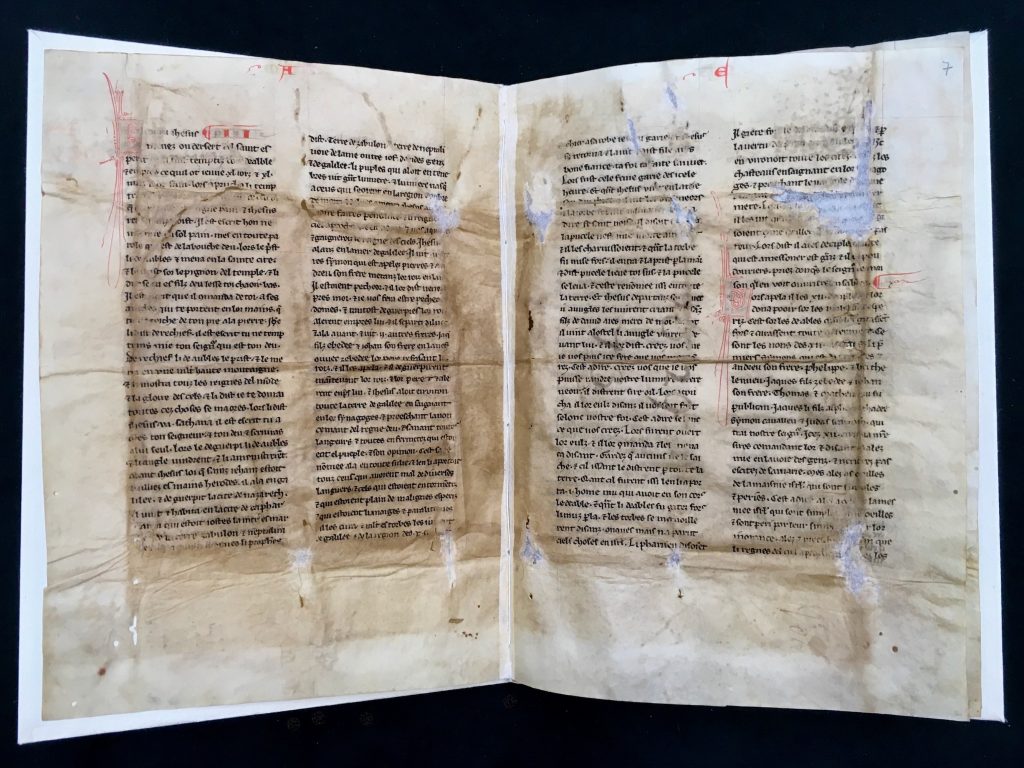

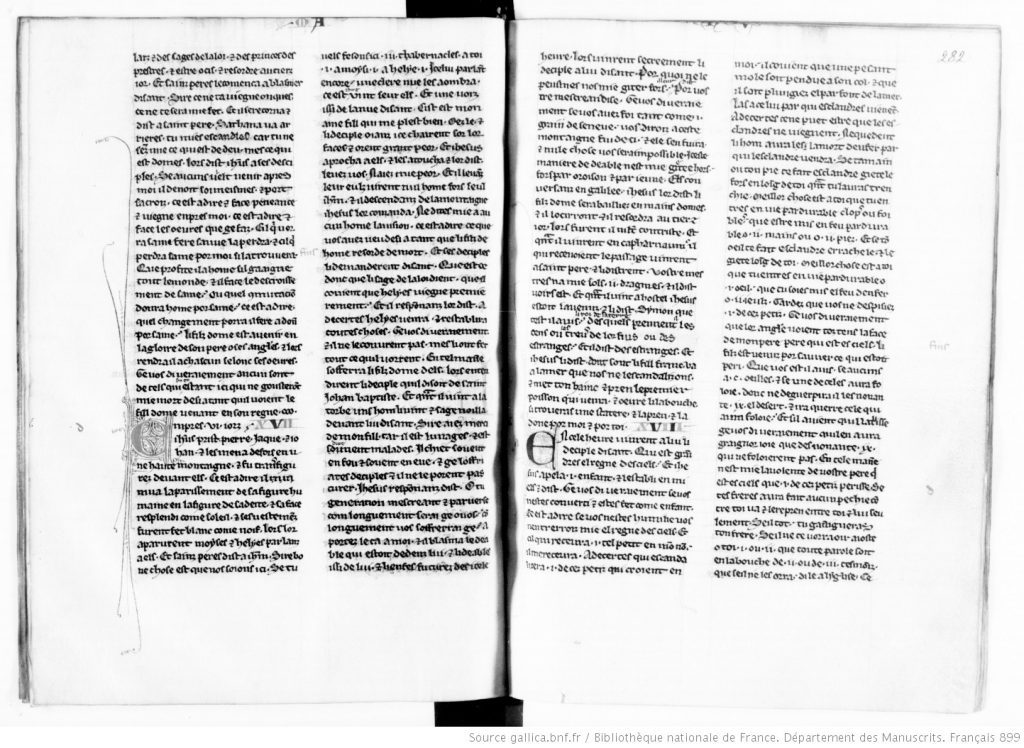

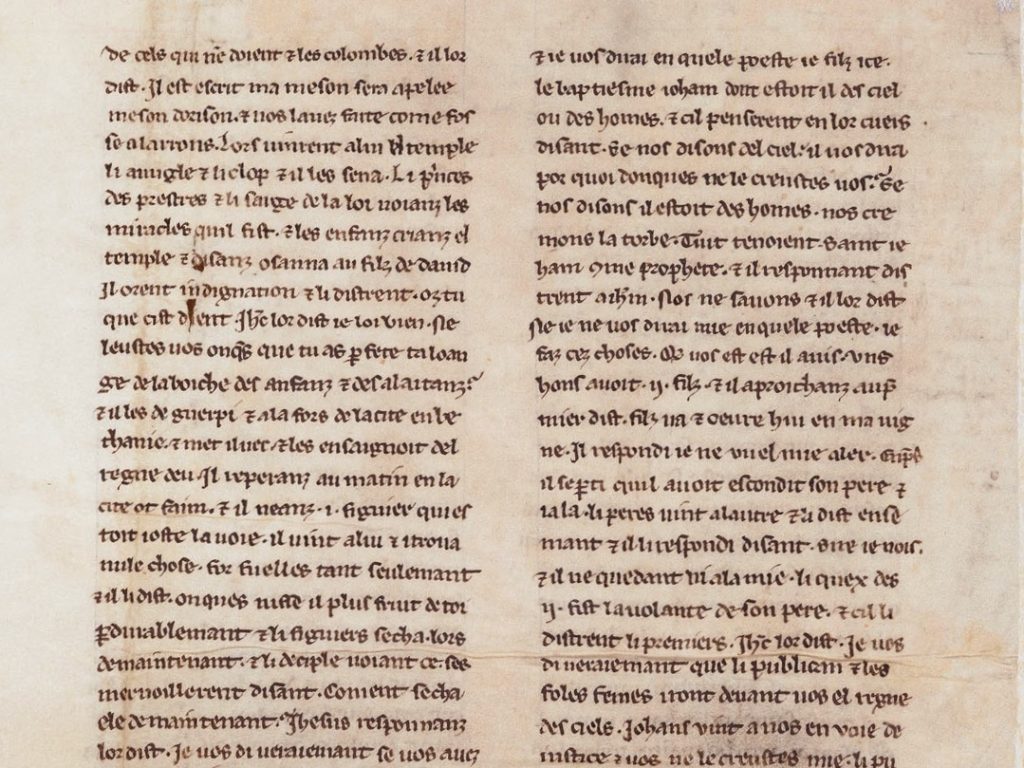

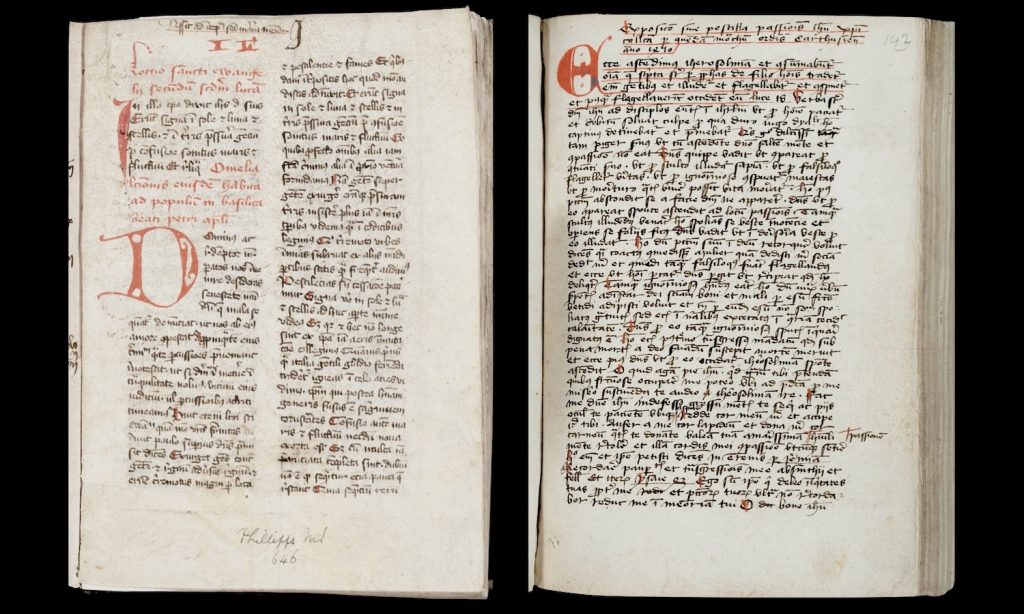

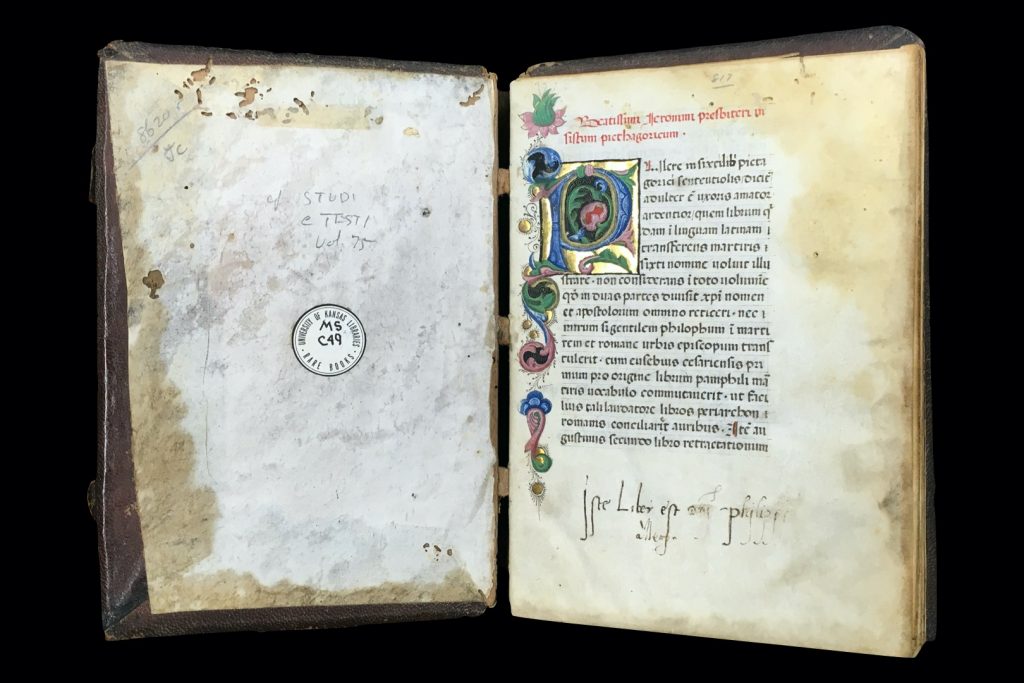

Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS C91 is a fifteenth-century collection of religious texts. It contains a copy of the Homiliae quadraginta in evangelia [Forty homilies on the Gospels] by St Gregory the Great (approximately 540–604), the Exposicio sive postilla passionis Ihesu Christi [An exposition or annotations on the passion of Jesus Christ] compiled by Herman Appeldorn (d. 1473) and a shorter text on the passion of Christ, also attributed to him in the manuscript.

Unlike many manuscripts whose origin and provenance are now lost to us, we have evidence that MS C91 comes from the medieval library of the Charterhouse of St Barbara in Cologne, Germany, a Carthusian monastery. St Bruno (approximately 1030–1101), who was educated in Reims, France, and who later became the Chancellor of the Archdiocese of Reims, founded the Carthusian Order in 1084 in the Chartreuse Mountains, north of Grenoble, France. This original establishment, known as the Grande Chartreuse, is the head monastery of the Carthusian Order, and Carthusian monasteries are known as “charterhouses” after Chartreuse. Despite St Bruno originally being from Cologne, there was no charterhouse in Cologne until December 12, 1334, when the Charterhouse of St Barbara was founded by the Archbishop of Cologne, Walram of Jülich (approximately 1304–1349). Although it had a difficult start due to political tensions in the region, the charterhouse began to prosper especially after it came under the protection in 1354 of Charles IV (1346–1378), King of Bohemia and later Holy Roman Emperor.

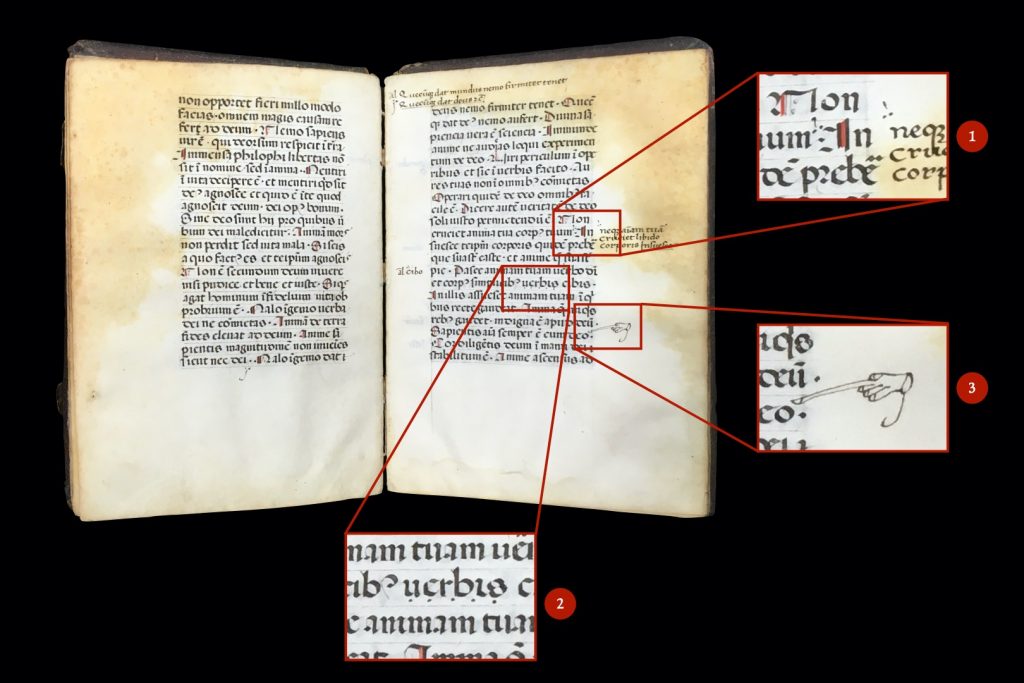

By the mid-fifteenth century the manuscript collection of the Charterhouse of St Barbara was the largest in Cologne, at least until the library and the neighboring buildings were completely consumed by a fire in November 1451. Some manuscripts, however, would have survived, for even though the Charterhouse of St Barbara had a separate library space, one did not need to be there to work with books. The Carthusians lived a solitary and contemplative life, and much work with manuscripts, including reading, copying, and writing commentaries was carried out by nuns and monks in the solitude of their cells. Therefore, although many books surely perished during this fire, scholars have argued that some of the manuscripts the monks were consulting at the time would have been spared.

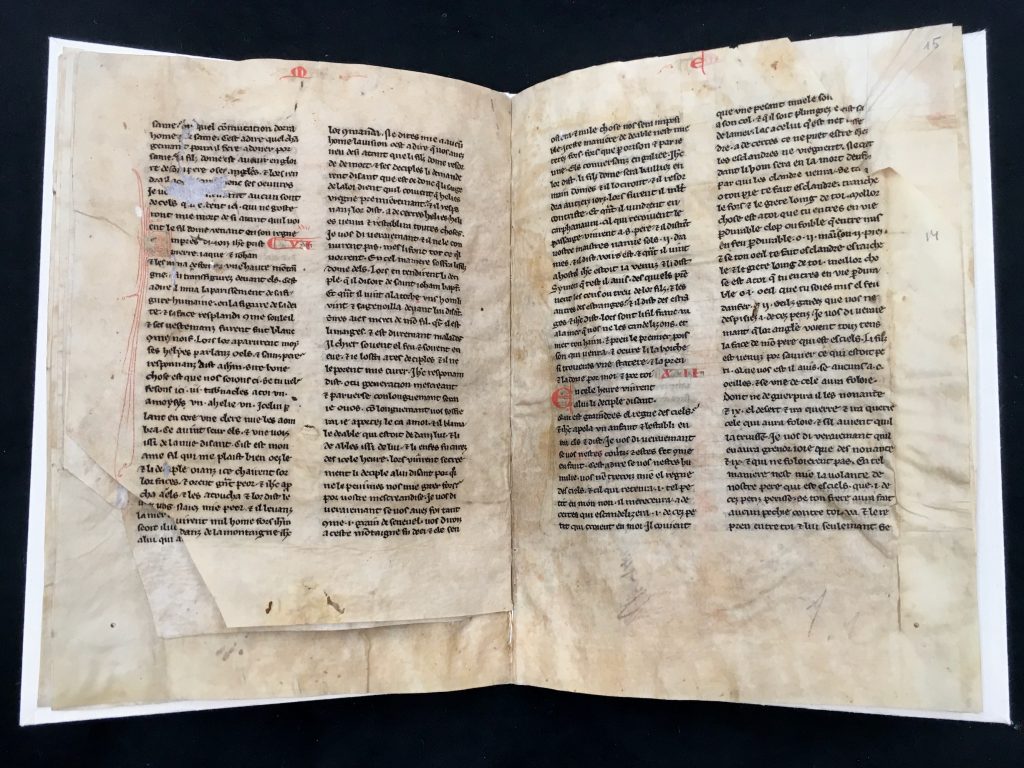

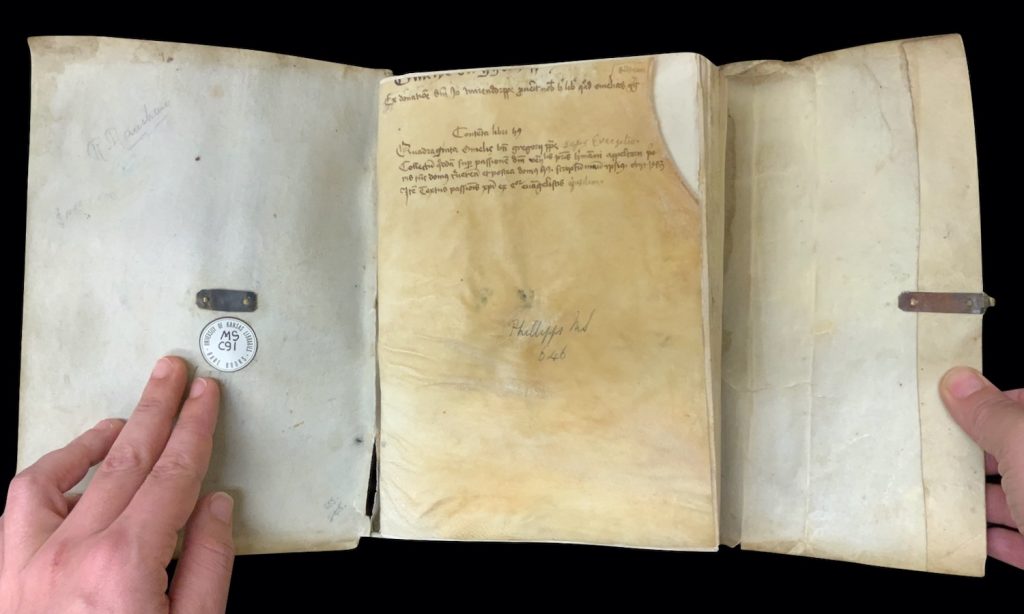

Following the 1451 fire, the collection of the Charterhouse of St Barbara in Cologne was swiftly rebuilt not only by the copying of new manuscripts by the members of the charterhouse but also through purchases and donations. MS C91 is the product of these efforts, probably put together when Herman Appeldorn was Prior of the Charterhouse of St Barbara between 1457 and 1472. MS C91 is in its original parchment limp binding with a fore-edge envelope flap that extends from the right (back) side of the cover and is secured with a brass clasp. The fifteenth-century shelfmark of the library of the Charterhouse of St Barbara is written on the front cover of the manuscript: “G.xlii.” In this system, the letter is thought to indicate the name of the author or the subject of the manuscript and the number possibly the order of acquisition. So, in the case of MS C91, “G” probably refers to Gregory, whose work is the first text in the manuscript, and “xlii” to no. 42. Another manuscript from the library of the Charterhouse of St Barbara in Cologne with a very similar binding, presumably bound around the same time as MS C91, is now held at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia (Ms. Codex 1164). No shelfmark survives on the front cover of this manuscript, but there is evidence that some writing was scraped off of the parchment and one may presume that the shelfmark was erased by a subsequent owner.

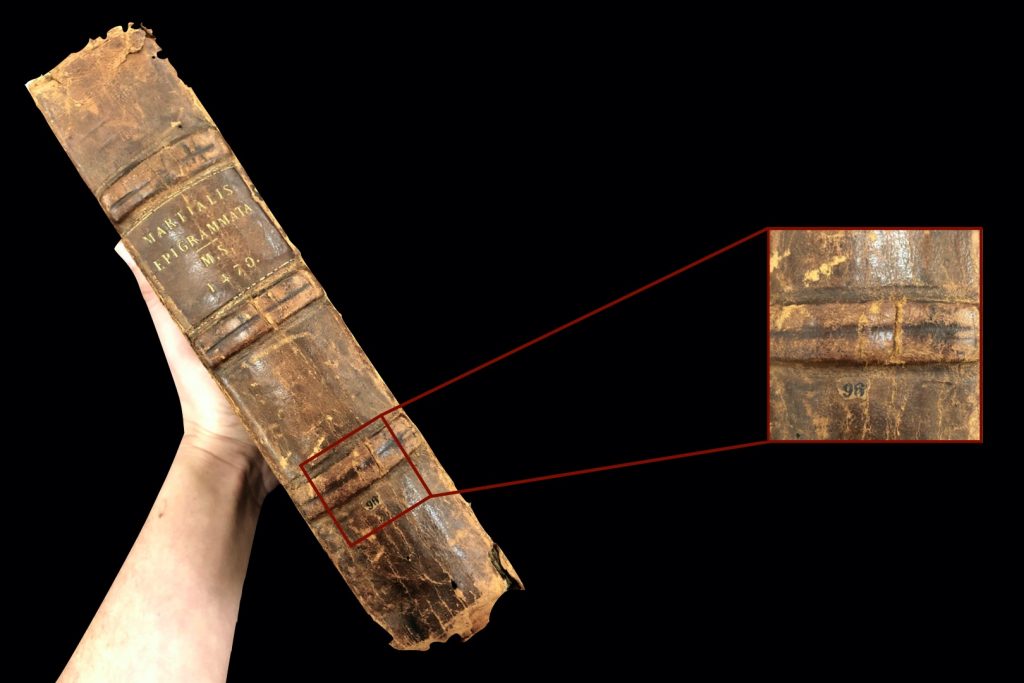

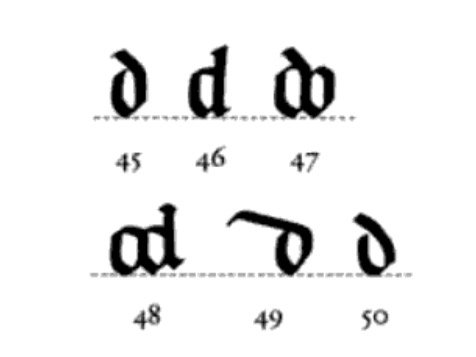

Although no medieval catalogs of the library of the Charterhouse of St Barbara with these shelfmarks survive, there are other manuscripts from the library with them. There are also several documents that detail the contents of the library from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, most of which have been preserved in the Historical Archive of the City of Cologne. For example, a shelf list edited by Richard Bruce Marks that was compiled in the second half of the seventeenth century includes over 550 volumes of manuscripts. In this document (Cologne, Historisches Archiv der Stadt Köln, Best. 233 Kartäuser, Repertorien und Handschriften, Nr. 14), MS C91 is assigned the shelfmark “OO 89.” In the shelf list, the print books are organized according to subject matter under the letters of the alphabet (A to H; J to N), with the letter O reserved for all manuscripts. The manuscripts are divided into four groups according to their size: O for folio, OO for quarto, OOO for octavo and OOOO for duodecimo. Measuring approximately 210 x 145 mm, MS C91 has one of these labels with “OO” adhered to its spine.

Furthermore, the short description for MS C91 in the seventeenth-century shelf list comes directly from the list of contents provided in a contemporary hand on the front flyleaf of the manuscript:

Conte[n]ta libri h[uius]

Quadraginta omeli[a]e b[ea]ti Gregorii p[a]p[a]e super evangelia

Collectu[m] q[uo]dda[m] sup[er] passione[m] d[omi]ni ven[erabi]lis p[at]ris H[er]ma[n]ni Appeltorn p[ri]oris tu[n]c dom[us] T[re]veren[sis] et postea dom[us] h[uius] scriptiu[m] man[u] ipsi[us] obiit 1473

Ite[m] textus passio[n]is Chr[ist]i ex [quattuor] eva[n]gelistis eiusdem.

This book contains:

Forty homilies on the gospels of the blessed pope St Gregory,

A certain collection on the passion of our lord by the venerable father Herman Appeldorn, then the prior of the house of Trier, and afterwards of this house, written by his own hand, died 1473,

Also a text on the passion of Christ from the four evangelists, by the same [Herman Appeldorn].

Above this brief table of contents on the first flyleaf of MS C91, there is also a donation inscription:

Ex donation[n]e d[omi]ni Jo[?] Warendorppe p[ro]ve[n]it nobis h[ic] lib[er] quoad Omelias Gregorii

This book, as far as Gregory’s Homilies, comes to us from the donation of Johann? Warendorppe.

Unfortunately, the identity of this donor Warendorppe is unknown; Richard Bruce Marks reports that there are eighteen people with the same name in the list of graduates from the University of Cologne before the year 1500 (p. 16). The donation inscription and the table of contents are written by the same hand, presumably around the same time the contents of the manuscript were copied. Taken together, they tell us that what is now the first part of the manuscript (Gregory’s Homilies) was commissioned by Warendorppe and that the remainder was authored and copied by Herman Appeldorn. These two parts must have been put together shortly after their copying, with the addition of the flyleaf with the donation and contents information when the manuscript was bound. There is very little known about Herman Appeldorn, although his name is recorded in other manuscripts as part of purchases and donations made to the library of the Charterhouse of St Barbara in Cologne during his priorship. He is thought to have composed three works: Sermones dominicales [Sunday Sermons], De passione domini [On the passion of Christ], and De institutione novitiorum [On the education of novices]. None of these works seem to have been published and it is possible that MS C91 contains the only copy of the De passione domini.

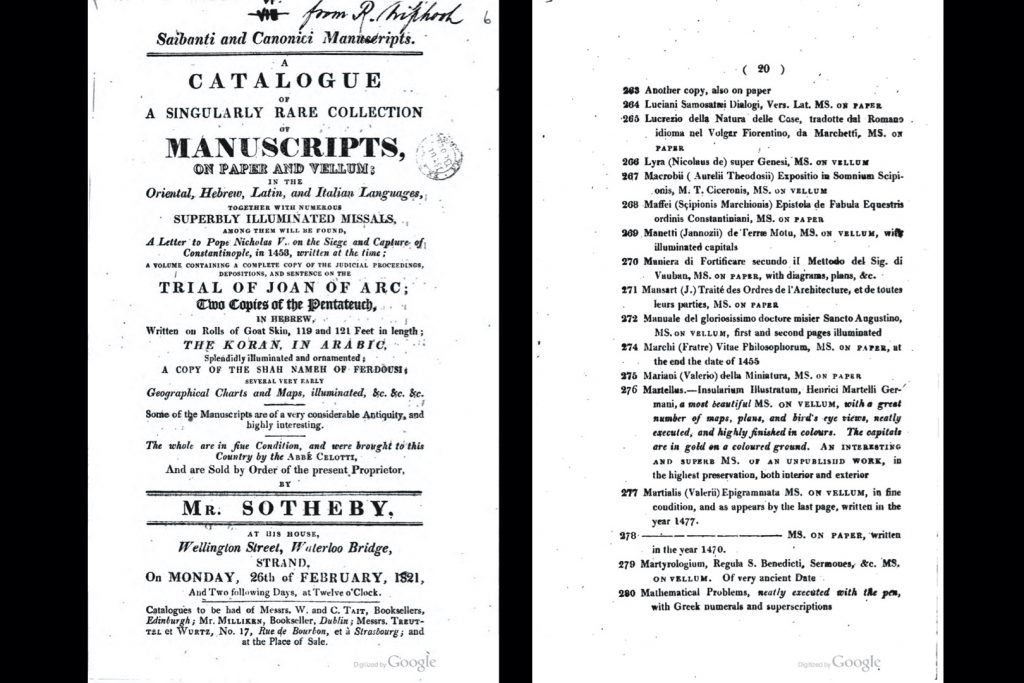

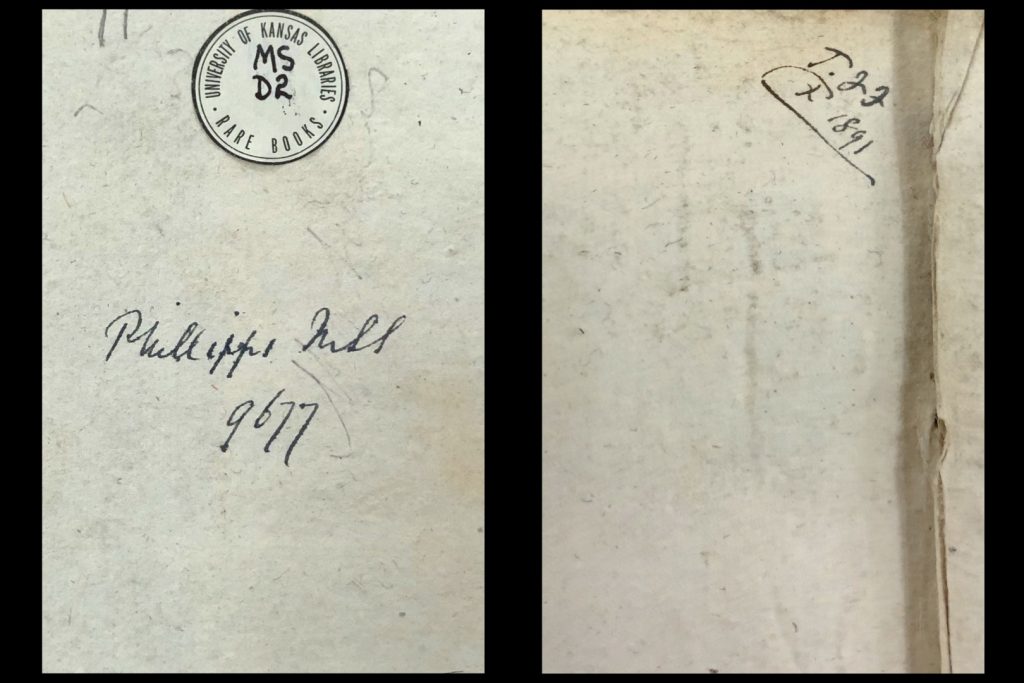

The recent provenance of MS C91 is quite well known. After the dissolution of the Charterhouse of St Barbara in Cologne in 1794 during the French Revolution, some of the manuscripts were sent to Paris, others to a new school founded in Cologne and the rest were sold. During these sales, some hundred and thirty-six manuscripts were acquired by the book and art dealer Johann Matthias Heberle (Antiquargeschäft mit Auktionsanstalt Cologne) and then sold in 1821 to Leander van Ess (Johann Heinrich van Ess, 1772–1847), a theologian and book collector from Warburg, Germany. MS C91 was one of these. Only a few years later, in 1824, Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792–1872) purchased the entire collection of Leander Van Ess, including those manuscripts that formerly belonged to the Charterhouse of St Barbara. In 1910, at the beginning of the twentieth century, as part of an auction of Phillipps manuscripts, MS C91 was sold by Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge to J. & J. Leighton, booksellers and bookbinders in London. Soon afterward, in 1912, the manuscript was purchased from J. & J. Leighton by Robert Ranshaw (1836–1924), a master draper and an art collector from Louth, Lincolnshire.

In his 1974 study, Richard Bruce Marks aimed at reconstructing the manuscript collections of the Charterhouse of St Barbara in Cologne and identified the current whereabouts of over 250 manuscripts that were included in the seventeenth-century shelf list. MS C91 was among those he was not able to locate. Indeed, Spencer Library holds two former Van Ess and Phillipps manuscripts from the library of the Charterhouse of St Barbara in Cologne, neither of which was identified by Marks: Phillipps MS 642 (now MS C64) and Phillipps MS 646 (now MS C91). Both of these manuscripts can now be added to the list.

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from Internationaal Antiquariaat (Menno Hertzberger & Co.) in September 1960, and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

- The most comprehensive study in English on the Library of the Charterhouse of St Barbara in Cologne: Richard Bruce Marks. The Medieval Manuscript Library of the Charterhouse of St. Barbara in Cologne. 2 vols. Analecta Cartusiana 21. Salzburg: Institut für Englische Sprache und Literatur, Universität Salzburg, 1974.

- Other blog posts from the “Manuscript of the Month” series on former Sir Thomas Phillips manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library: https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/tag/sir-thomas-phillipps/

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

![Image showing the colophon in MS D2 on folio 184v, in which the scribe mentions their name (“Iacobus Tirabuschus B[er]gomensis”) and the date of the completion of the copying of the manuscript (“MoccccoLxxo die decimo nono Octobris”) in Martial, Epigrams, Italy (?), October 19, 1470. Call # MS D2.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/KSRL_MS_D2_folio_184v_detail-1024x683.jpeg)