Adjustable Conservation Book Support: An open-design conservation tool arrives at KU Libraries

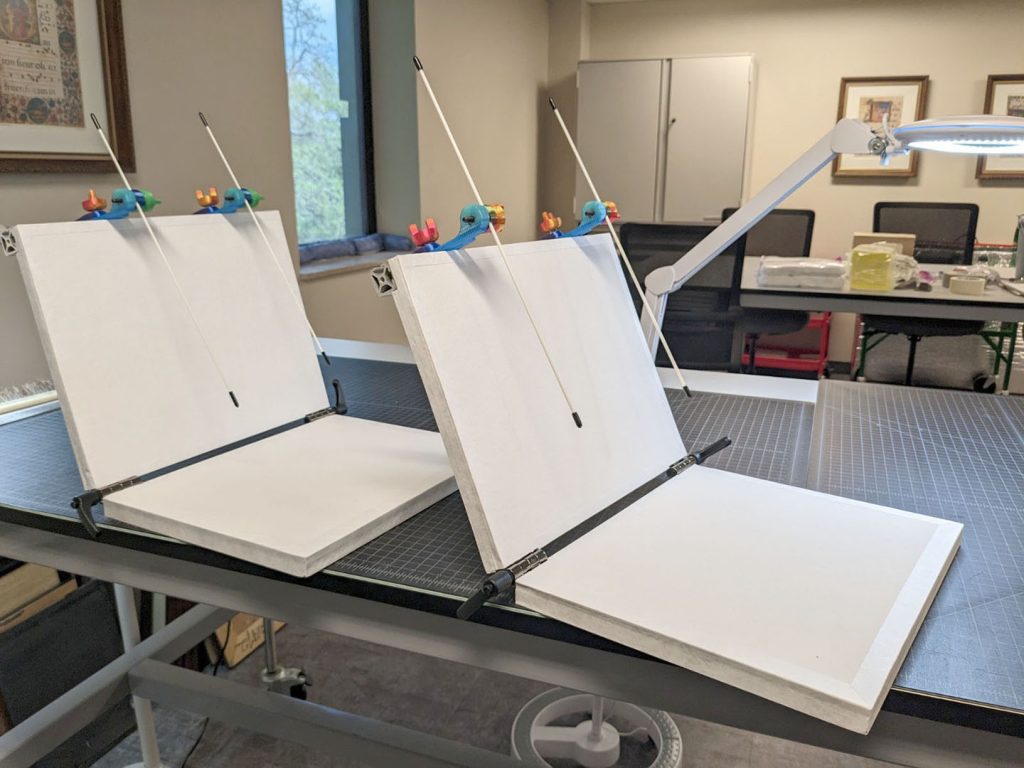

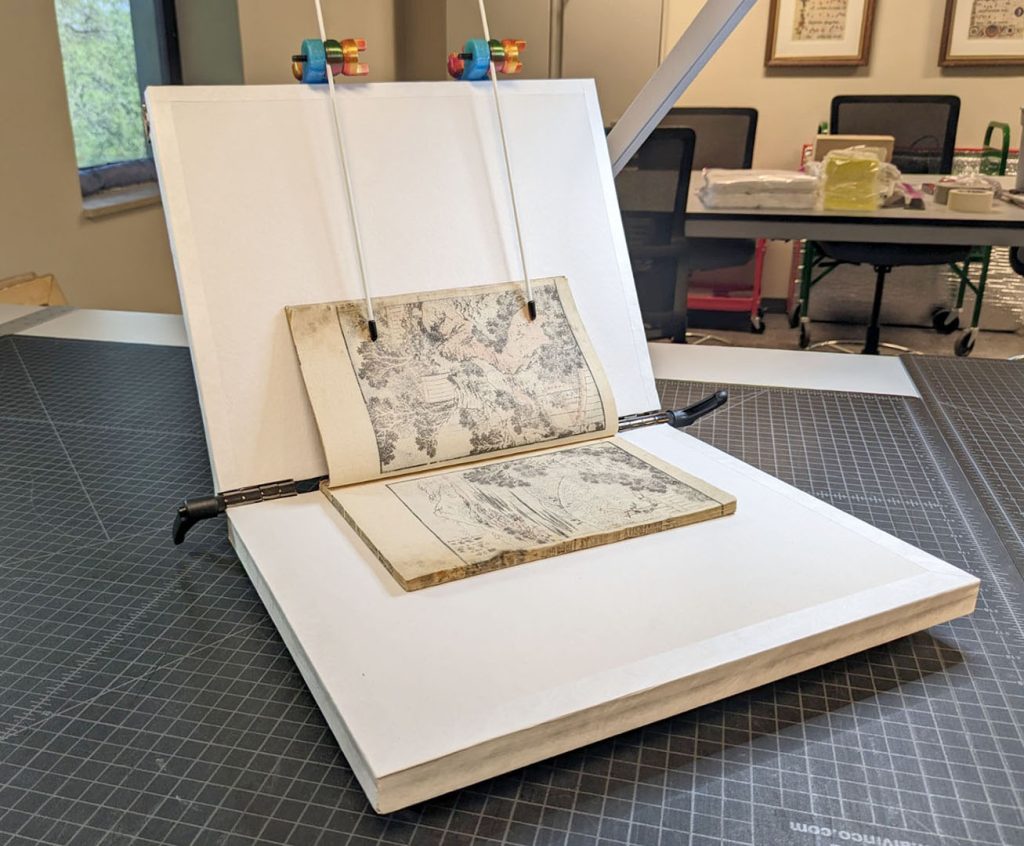

May 16th, 2023The conservation lab at the University of Kansas Libraries is now home to a pair of Adjustable Conservation Book Supports, or ACBS’s. The ACBS is a hinged cradle that supports a book during conservation treatment; fiberglass rods gently hold the book open in almost any desired position, a feat that can be difficult or impossible to achieve with our usual system using weights and fixed cradles or foam wedges, or other rigged-up arrangements. The ACBS was designed and developed at Northwestern University by conservator Roger Williams in collaboration with students in Northwestern’s School of Engineering. Williams wrote about the process in this blog post: Collaborating with engineering students to create an open-design conservation tool – LIBRARIES | Blog (northwestern.edu). We learned about the ACBS when Williams presented a webinar about the project during the COVID-19 pandemic, at a time when many conservators were unable to work in their labs. We and our colleagues around the world spent much of our pandemic work-at-home time learning and sharing on online platforms, saving up the new knowledge to try out when we were back in our workspaces.

One of Williams’ goals when creating the ACBS was to make it freely available and customizable – an open-design tool that could be built with readily available supplies and that could be adapted and improved upon by the conservation community through use and experimentation. Conservators at the Auckland War Memorial Museum in New Zealand took up this challenge and created an (also open access!) alternative design for the two clamps that sit at the top of the ACBS. The 3D-printed Auckland clamp design increases the range of motion of the fiberglass rods, adding even more functionality to the ACBS. (See their blog post: Newest Trick in the Book – Blog – Auckland War Memorial Museum (aucklandmuseum.com))

We wanted to build an ACBS for our lab, and we definitely wanted those clamps! We knew that KU Libraries had a 3D printer in our new Makerspace, so we reached out to Associate Librarian Tami Albin for her help. The Makerspace was in its early days, and Tami had been experimenting with the 3D printer, getting to know its capabilities and the properties of different filaments. We downloaded the files for the Auckland clamps and sent them to Tami. While Tami worked on the clamps, collections conservator Roberta Woodrick ordered the rest of the parts we needed for our ACBS’s (we had decided to build two), and she and I assembled them up to the point of adding the clamps. A few weeks later, Roberta and I visited the Makerspace to see the results of Tami’s first tests. Tami described how the 3D printer works, showed us the printed clamp parts, and explained how the type of filament affects the finished 3D print. She had printed an assortment of sample parts for us; we brought them back to the lab and examined each one to find those that had the look, feel, and weight that suited us, and to test the fit on the ACBS’s.

After we’d selected the samples that we liked best, we reported back to Tami and she set to work printing the final pieces. We were excited to get the email from her letting us know that the parts were ready! We gave Tami free rein to choose the filament colors, and she came through with a selection of bright, cheerful colors that add some fun and personality to our ACBS’s.

With the clamp parts in hand, we had a few more steps to go before the ABCS’s would be ready to use. I put together the clamp assembly and found that our off-the-shelf bolts were about 1mm too long, preventing the clamps from being fully tightened. I found my set of jeweler’s rasps (saved from a metals elective I took back in art school – conservators love to appropriate tools of many trades!) and used one to file down the ends of the bolts until they fit correctly.

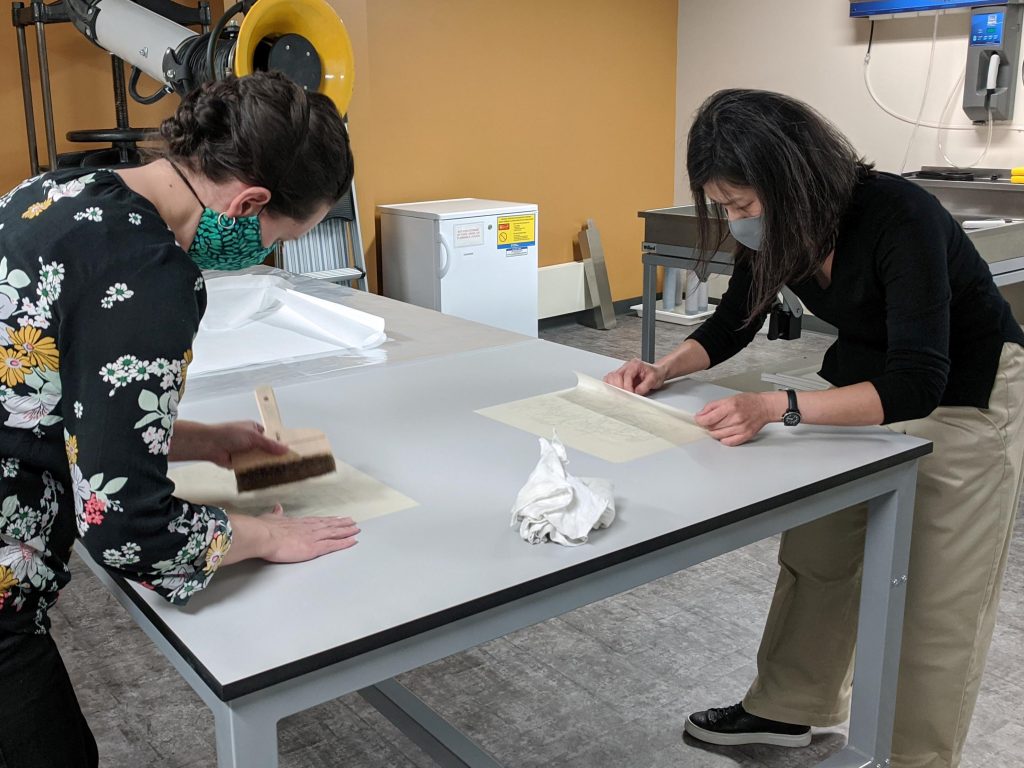

With the clamps assembled, the last step was to fill in the sides of the ACBS’s to bring the surfaces level with the thick hinges. Per Williams’ instructions, I filled the lower boards of the ACBS’s with scraps of binder’s board, a heavier material, and the upper board with corrugated plastic, a lighter material, to help balance the ACBS. I then covered each side with blotter and sealed the edges all around with Tyvek tape.

Conservation is always a collaborative effort, and we are so grateful for Tami’s contribution to this project. We are looking forward to all the ways that we can put these new tools to use in our work caring for KU Libraries’ collections.