January 13th, 2015 Linnnaeus (whose citation at the end of a binomial is simply “L.”) invented a practical system for the classification of plants and animals; more importantly, he established a uniform method of referring to species by two Latin words–a reform that led eventually to binomial nomenclature. Although his classification system was superseded, his principles of nomenclature continue to provide the rules for application of names to thousands of species of animals and plants newly identified every year. Volume 1, Animalia, of the tenth edition of the Systema Naturae (1758), is one of the most important books in the history of science, for it marks the beginning of the modern zoological nomenclature and systematics. In it, Linnaeus first consistently applied binomial nomenclature to the whole animal kingdom.

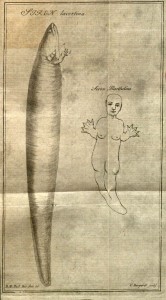

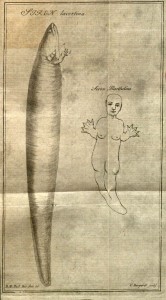

Image from Siren lacertina, 1766. Linneana B65 v.6:146, Special Collections

Unfortunately the great Linnaeus had little love for herps, thought them “disgusting,” and would have done well to adopt the classifcation system of John Ray. We quote, in rough translation, from the Systema: “Amphibia are loathsome because of their cool and colorless skin, cartilaginous skeleton, despicable appearance, evil eye, awful stench, harsh sound, filthy habitat, and deadly venom; and so God has not seen fit to create many of them.” Many of Linnaeus’s descriptions were based on those in books by Aldrovandus, Seba, Catesby, Jonstonus, and others. His use of the word “Amphibia” denoted not only all reptiles and amphibians, but also the cartilaginous fishes.

This work is the doctoral dissertation of one of Linnaeus’s students; it was the tradition of the day for a professor to write the thesis, but the student “respondent” had to defend it and pay for its publication.

Sally Haines

Rare Books Cataloger

Adapted from her Spencer Research Library exhibit and catalog, Slithy Toves: Illustrated Classic Herpetological Books at the University of Kansas in Pictures and Conservations

Tags: binomial nomenclature, Carl von Linee, Linnaeus, Sally Haines

Posted in Exhibitions, Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »

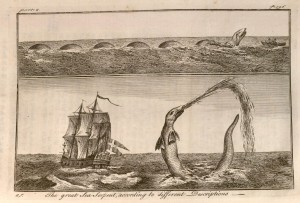

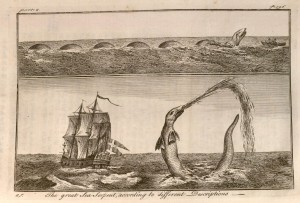

September 29th, 2014 When it comes to creating an exhibition of illustrated books with a biological theme, a fabulous sea monster can be almost anything in the eye of the creator, and by power of suggestion, in the eye of the beholder. Some historians of biology have suggested that the basis-in-fact for the Scandinavian sea monster, Bishop Pontoppidan’s kraaken in this case, was a whale, so the image was used in a past show of whaling books in the Spencer Library. But Moby Dick‘s author, Herman Melville, as well as marine biologist Jacques-Yves Cousteau, thought it more likely that the real basis for the legends was the giant squid. For purposes of this post, it’s a sea serpent, but we intend to keep it in mind for our up-and-coming Squid Exhibit.

Image from Erik Pontoppidan (1698-1764). The natural history of Norway. London: 1755.

Call number: Ellis Aves E333, Special Collections.

The Danish original of this natural history was published in Copenhagen (1752-1754), and is of interest chiefly for its accounts of the myths connected with whales and other natural curiosities such as the fabeled kraaken.

Sally Haines

Rare Books Cataloger

Adapted from her Spencer Research Library exhibit and catalog, Slithy Toves: Illustrated Classic Herpetological Books at the University of Kansas in Pictures and Conservations

Tags: Erik Pontoppidan, Herpetology, natural history, Norway, Sally Haines, Sea serpent

Posted in Exhibitions, Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »

August 29th, 2014 The late marsupialist John A.W. Kirsch was interviewed by a local (Peruvian) newspaper while on a collecting trip in South America back at the end of the 1960s. He described the kinds of animals he was looking for and was shocked to see the headline a few days later: KANGAROOS ON MACHU PICCHU.

While it’s true that the mammal group we call marsupials includes the kangaroos, wallabies, wombats, koalas, and bandicoots that are usually associated with Australia, and that the New World once did boast a rich and diverse marsupial fauna, most of the New World forms are now extinct and, sad to say, there are no kangaroos on Machu Picchu.

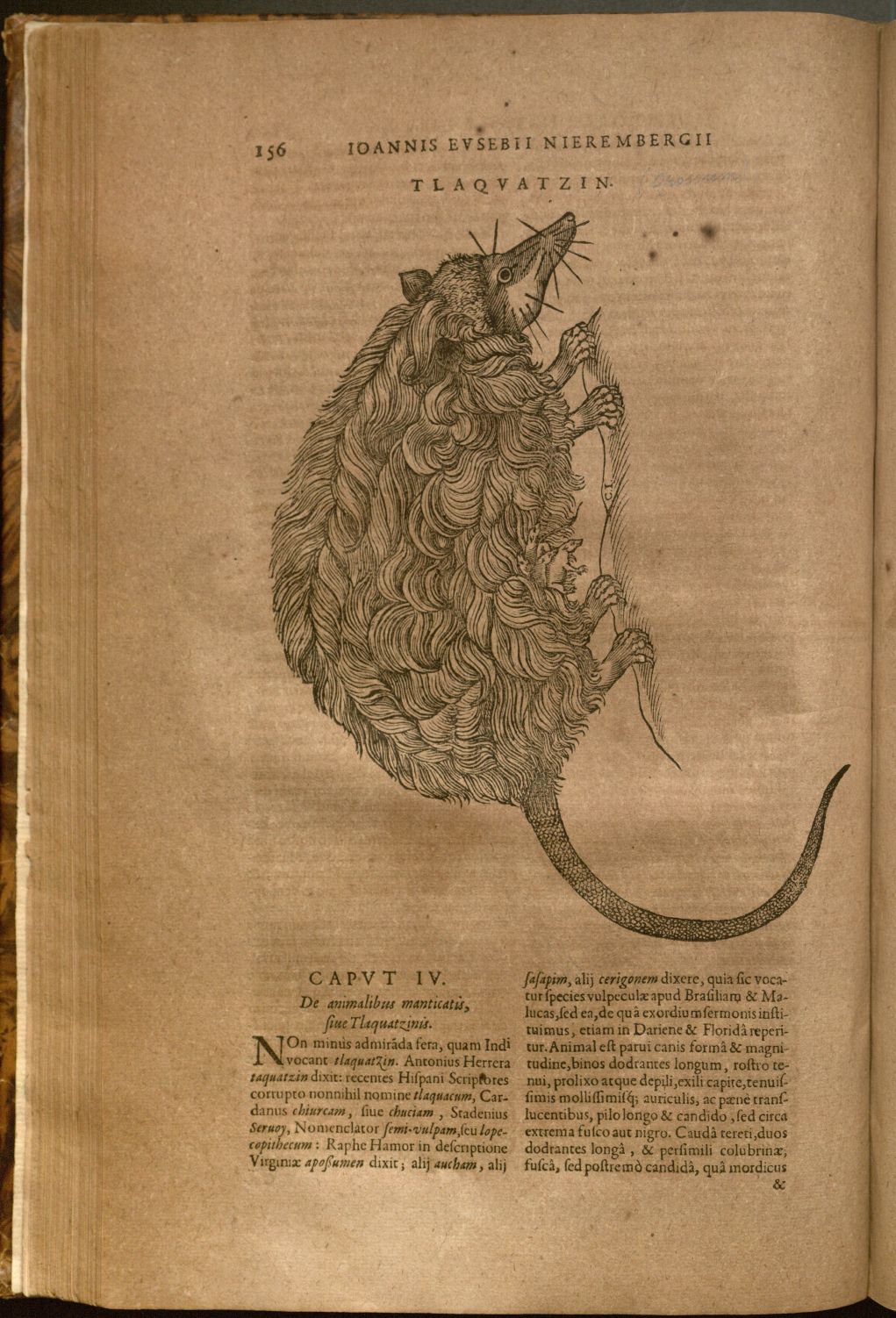

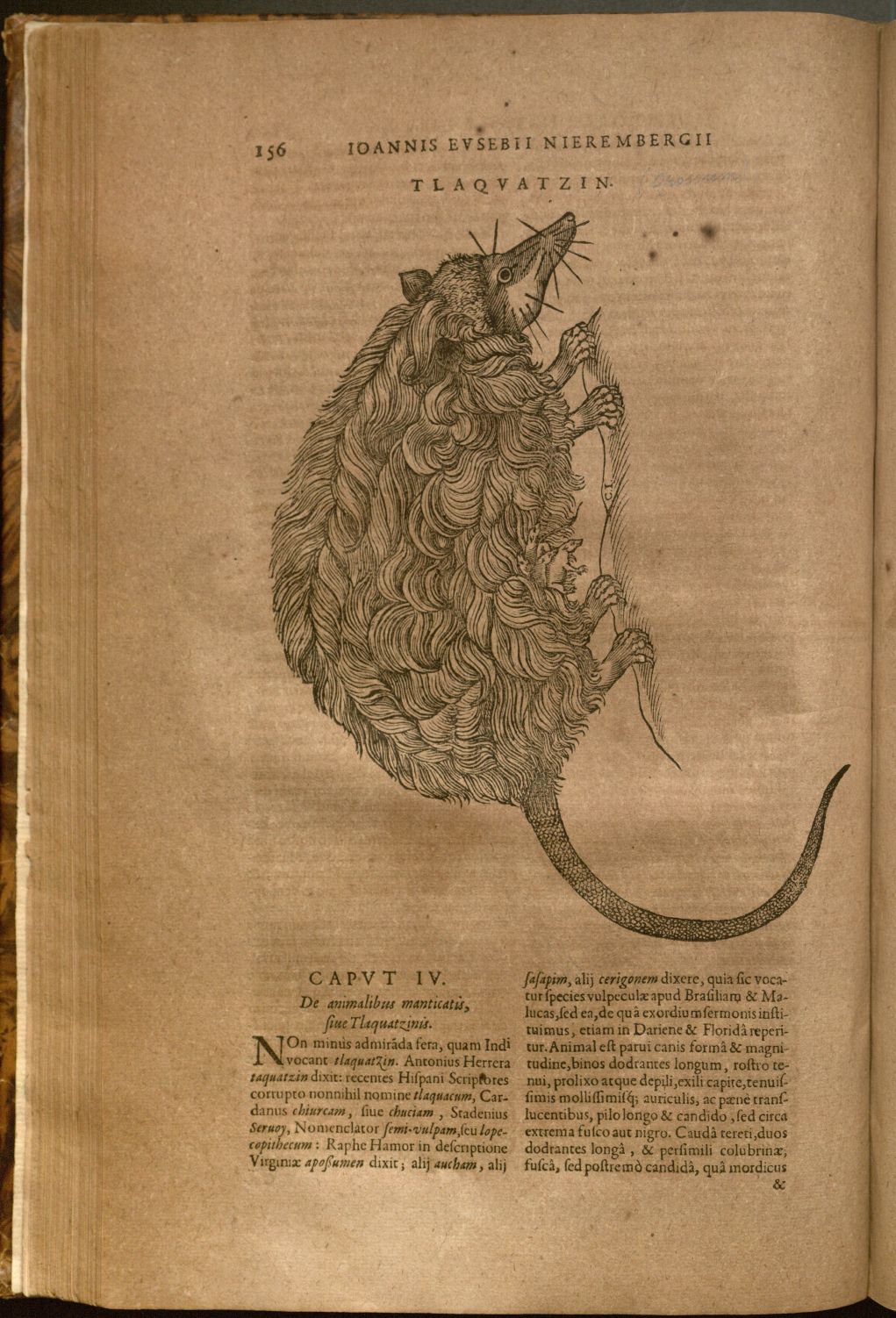

Opossums (and yes, there are several pictured above): Juan Eusebio Nieremberg (1595-1658). Historia naturae. Antverpiae: ex Officina Plantiniana Balthasaris Moreti, 1635. Call Number: Summerfield E1105. Click image to enlarge (and reveal the well-camouflaged opossum young.)

The marsupial heyday began to end circa three million years ago when a land bridge over the Isthmus of Panama provided for northern migration of animals including the ancestors of our familiar opossum, who dates back to around 35 million years ago and looks today pretty much the same as he did then. During the same period, some of the northern placental mammals migrated south over the same land-bridge. Thus, for example, it appears that the placental sabre-toothed tiger from the North began to compete with the marsupial sabre-toothed tiger and soon put him on the road to extinction. But the marsupials are survivors, nevertheless, and the American opossum, the only one of the family in North America, is just one of seventy some opossum species to survive; the ‘possum family is restricted to the New World, and except for Didelphis virginiana, whose range extends from southern Canada into Central America, the rest of the family is restricted to Central and South America.

Earlier travel accounts and herbals had described the plants and animals of the New World, but Juan Eusebio Nieremberg’s account was the first comprehensive natural history of the area, dealing primarily with Mexico and the West Indies. This illustration of the Virginia or American opossum is the earliest printed portrait of the earliest discovered (by Europeans, at least) marsupial anywhere.

Sally Haines

Rare Books Cataloger

Adapted from her Kenneth Spencer Research Library exhibit, The Haunted Forest: New World Plants & Animals (1992).

Tags: Haunted Forest (exhibition), Historia naturae (1635), Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, marsupials, natural history, Opossums, Sally Haines

Posted in Exhibitions, Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »

August 8th, 2014 A number of works in the Kenneth Spencer Research Library’s collection of Polonica are a good source for the study of Polish costume: the chromolithographs by Racinet, engraved colored plates by Jacquemin, colored and uncolored plates in the two volumes of Zaydler, and plates in the costume books by Kretschmer and Vecellio.

“Harvest-home in the environs of Sandomir” from Jozef Zienkowicz’s Les costumes du peuple Polonais. A Paris: Librairie Polonaise; A Strasbourg: chez l’éditeur; A Leipzig: chez F.A. Brockhaus, 1841. Call Number: D819. Click image to enlarge.

The colored lithographs of Zienkowicz’s Les costumes du peuple Polonais are particularly interesting: “Harvest-home in the environs of Sandomir” (above) illustrates the rich harvest tradition of a country that until recently was primarily agricultural. Poles today celebrate an annual Harvest Festival in early September. In olden days the best girl reaper would bestow on the master of the house the gift of a wreath of wheat and rye adorned with flowers, fruits, and ribbons; feasting and merry-making followed the ceremony. Although folk costumes are not now in general use in Poland and are worn mostly for festivals and national celebrations, Poles in rural areas wear folk dress on church holidays and for family celebrations such as weddings.

Sally Haines

Rare Books Cataloger

Adapted from her Kenneth Spencer Research Library exhibit, Poland: A Thousand Springtimes.

Tags: Costumes, Jozef Zienkowicz, Les costumes du peuple Polonais, Poland, Sally Haines

Posted in Exhibitions, Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »

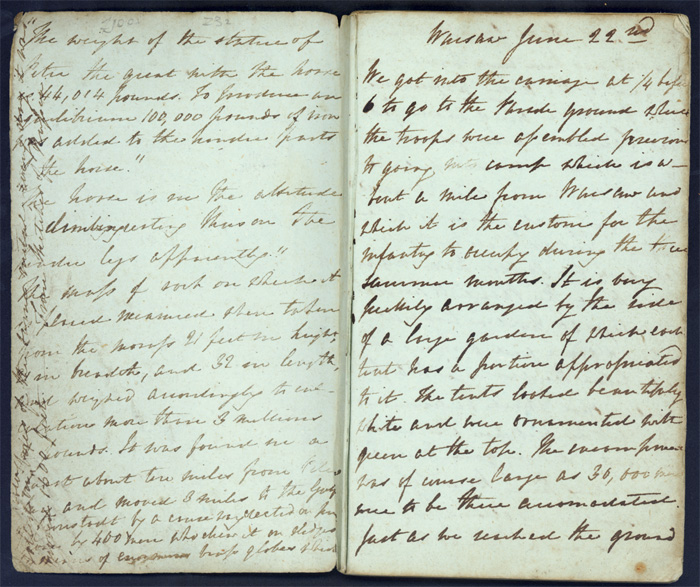

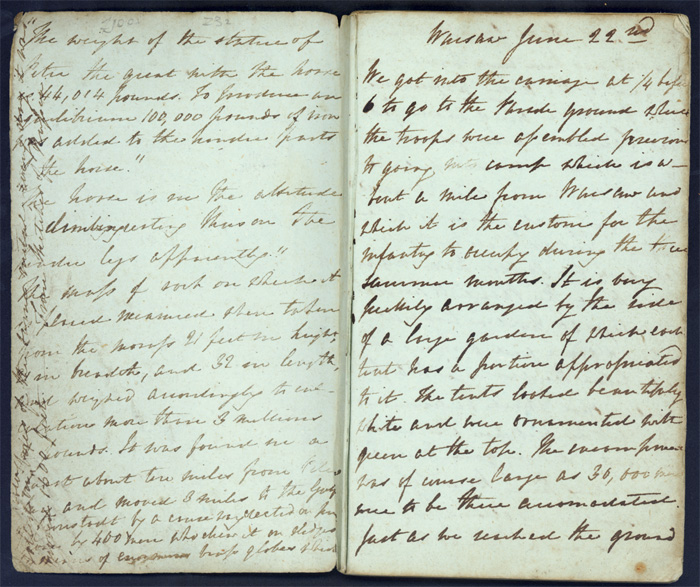

June 27th, 2014 If you’re interested in matters Polish and Russian or in travels in Slavic lands and in sights seen through western eyes AND if you can read this page from the manuscript diary of an Englishwoman traveling in the summer of 1828 (186 years ago!), then YOU may be the person to transcribe the contents of this little volume. You will get to know “Roberta” and “Mr. Sayer” (their real names), who were her companions on the trip. We can picture Ms. English Lady settling into the pension at night to write … Inside the front cover she begins, “The weight of the statue of Peter The Great …” You’ve seen the blurb; now read the book!

An English Lady: An anonymous manuscript travel-diary, a detailed account of the sights, costumes, social services, village and town life, war aftermath, travel mishaps in Russia and Poland. Warsaw-Smolensk-Moscow-Novgorod-St. Petersburg. 22 June to 21 July 1828. Call Number: MS B144. Click image to enlarge.

Sally Haines

Rare Books Cataloger

Adapted from her Spencer Research Library exhibit, Frosted Windows: 300 Years of St. Petersburg Through Western Eyes.

Tags: 19th Century, Frosted Windows, manuscripts, Poland, Russia, Sally Haines, travel diaries, Warsaw

Posted in Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »