Collection Snapshot(s): Marcas de fuego

May 11th, 2021

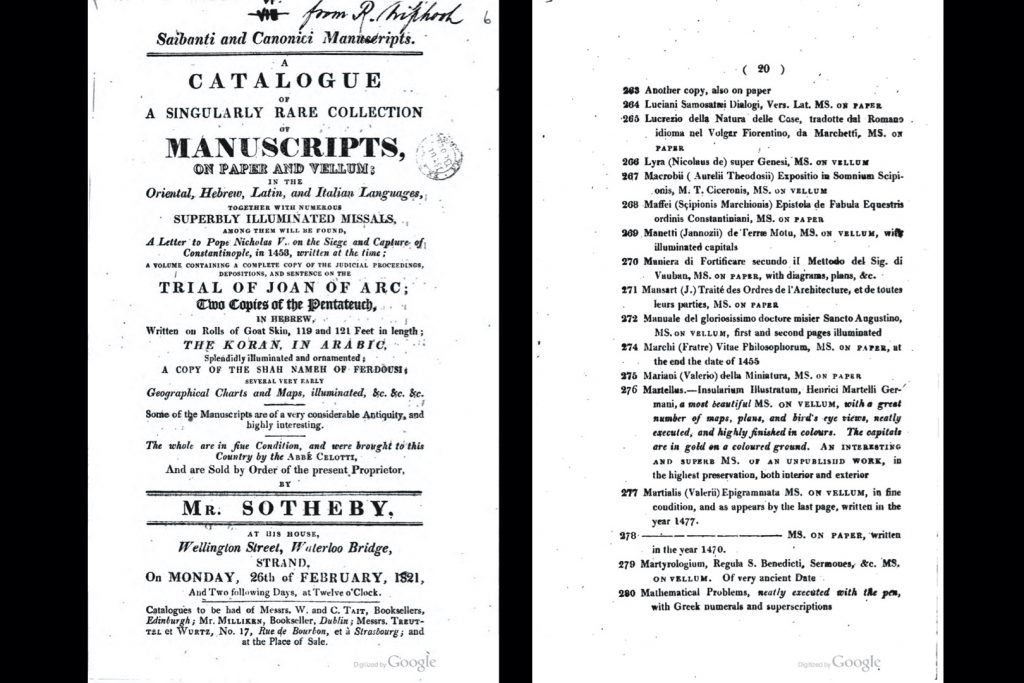

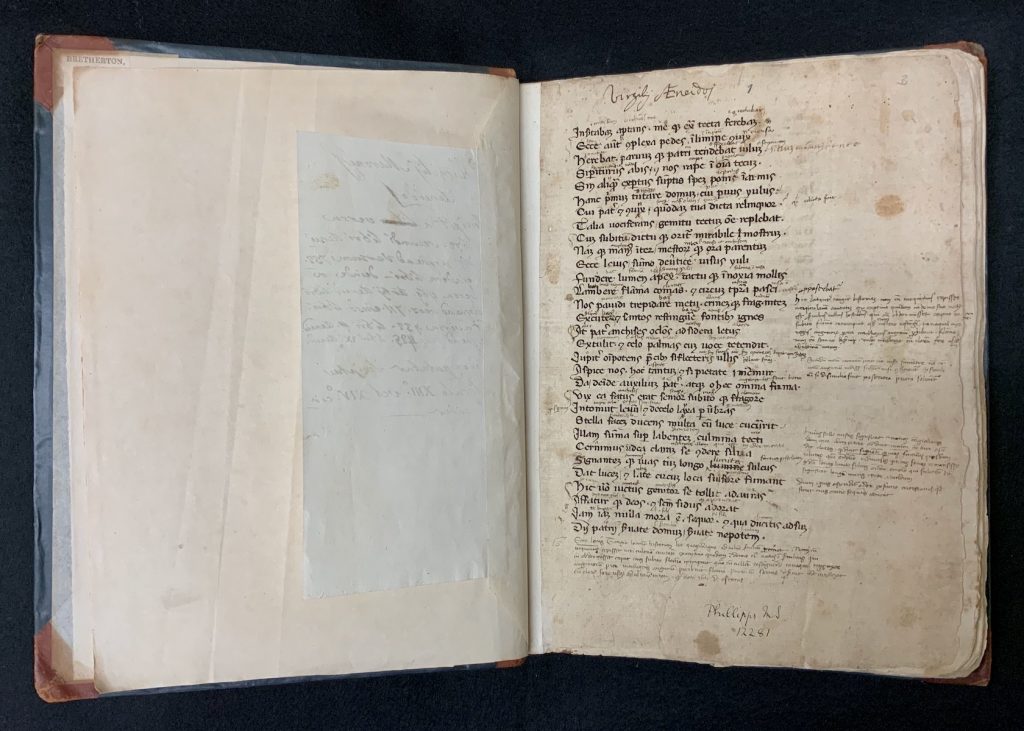

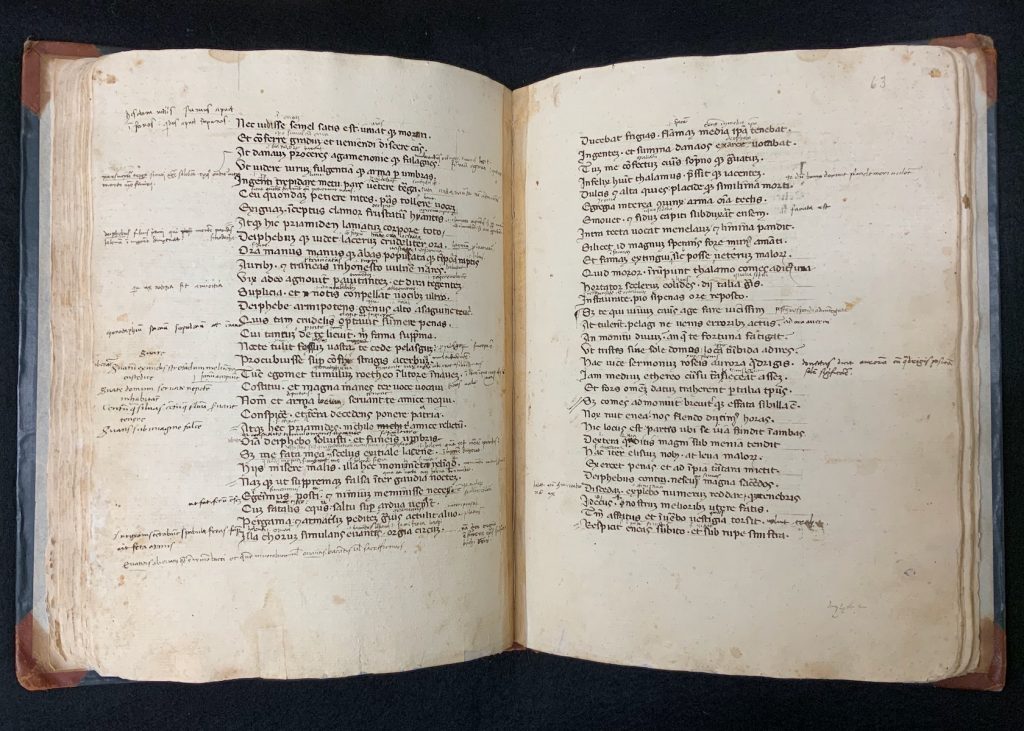

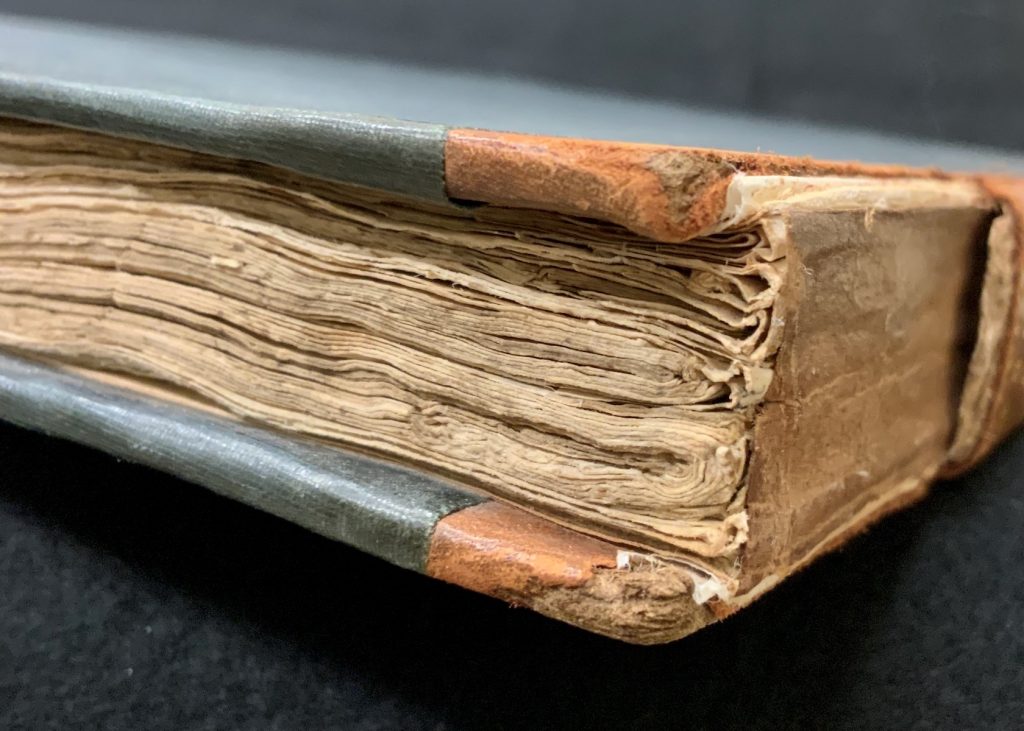

Today we share two examples of “marcas de fuego” from Spencer Research Library’s collections. In colonial Mexico, “marcas de fuego” (that is, “marks of fire” or fire brands) identified a book as belonging to a particular religious order or institution. This identifying emblem (or sometimes a set of stylized initials or a name) would be burned into the edge of the text block of a book using a hot metal instrument. The scholars and librarians associated with the Catálogo Colectivo de Marcas de Fuego (Collective catalog of fire brands) date this practice from the second half of the 16th century into the first decades of the 19th century.

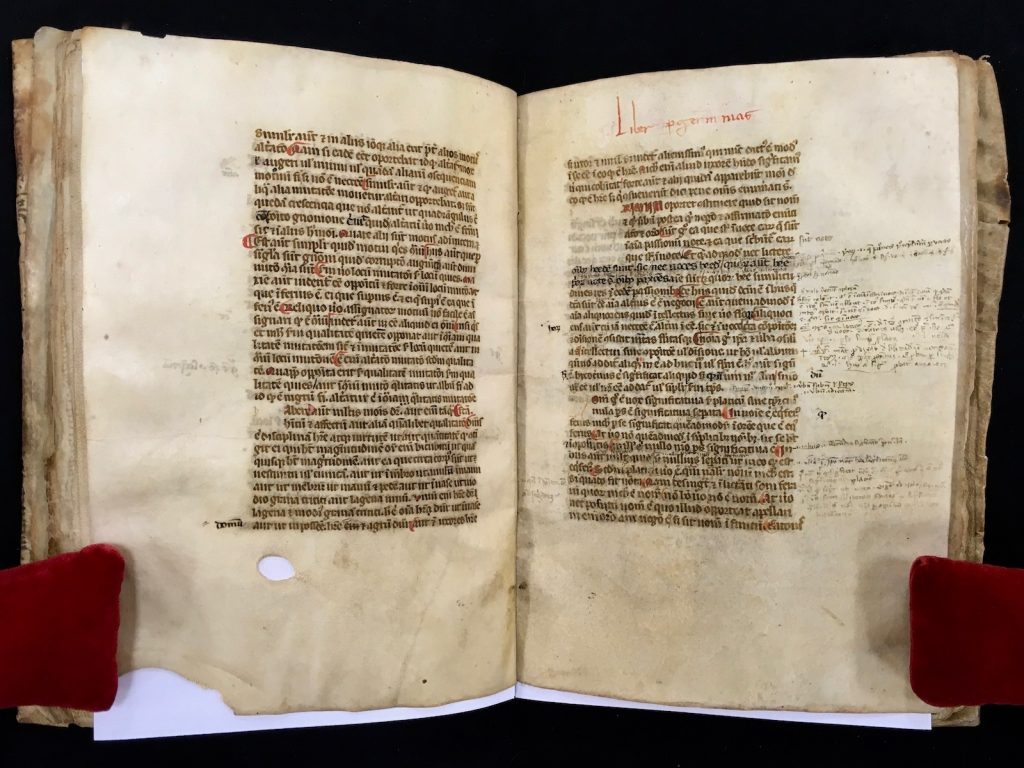

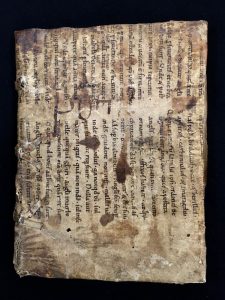

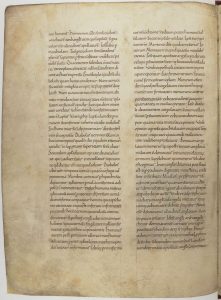

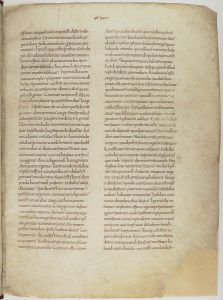

The marcas de fuego shown above appear on the top edges of the two parts of Spencer Research Library’s copy of Fray Juan Bautista’s Advertencias para los confesores de los naturales. Printed in Mexico City in 1600 (Parte 1) and 1601 (Parte 2), Bautista’s Advertencias was a manual offering guidance for priests taking the confessions of the indigenous peoples of “New Spain.” Printing came to the Americas in 1539 when Juan Pablos established a printing press in Mexico City. Bautista’s text is included in that first group of editions (roughly 220 in Mexico City and 20 in Lima, Peru) printed in the Americas prior to 1601. These are sometimes known in Spanish as “Incunable Americano,” after the practice of calling books printed in Europe prior to 1501—the “cradle stage” of printing—incunabula.

Interestingly, although Spencer Research Library acquired the two parts of Bautista’s Advertencias together from the California-based bookseller Zeitlin & Ver Brugge, their marcas de fuego suggest that the two separate volumes haven’t always resided together. Using the enormously helpful Catálogo Colectivo de Marcas de Fuego, we’ve been able to identify the fire brand that appears on each of the two volumes.

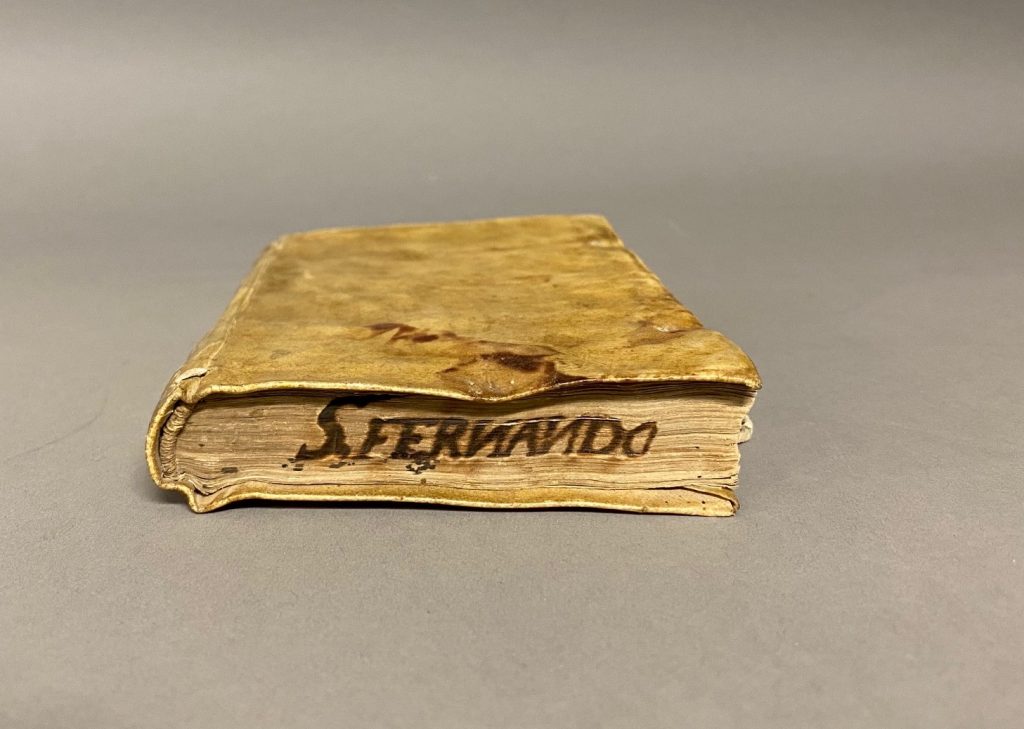

The marca de fuego that appears on “Parte 1” is that of the Colegio de San Fernando in Mexico City (see this entry in the Catálogo Colectivo for comparison). We’ll admit that this marca is among the more self-evident! The Colegio de San Fernando was founded in the 1730s as a Franciscan missionary college or seminary. Since one of its primary purposes was to train priests for conducting missionary work with indigenous peoples, it’s not surprising to see a copy of Bautista’s Advertencias with the marca de fuego of the Colegio de San Fernando.

The marca de fuego on “Parte 2” appears to be that of the Convento del Carmen in Atlixco, Puebla (see this entry for comparison). The term “Covento” in the Spanish colonial context refers to complex or facility used by a religious order, without the strong connotation of a female order present in the English term “convent.” Founded by the Carmelites, the Convento and the associated church were built the during the first two decades of the 1600s. The marca contains several elements of the Carmelite shield (the cross, the mount, and two of its characteristic three stars), and, as the Catálogo Colectivo entry for the marca notes, the initial “A” at the bottom of the marca might be an abbreviation for Atlixco. The “Convento” was dissolved in the mid 19th century and its belongings sold, but the much of the building structure still stands (with a more modern façade), though it did sustain damage in the 2017 earthquake that hit the region.

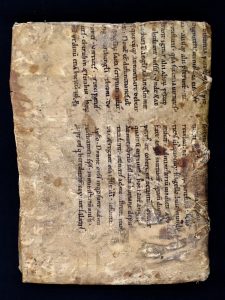

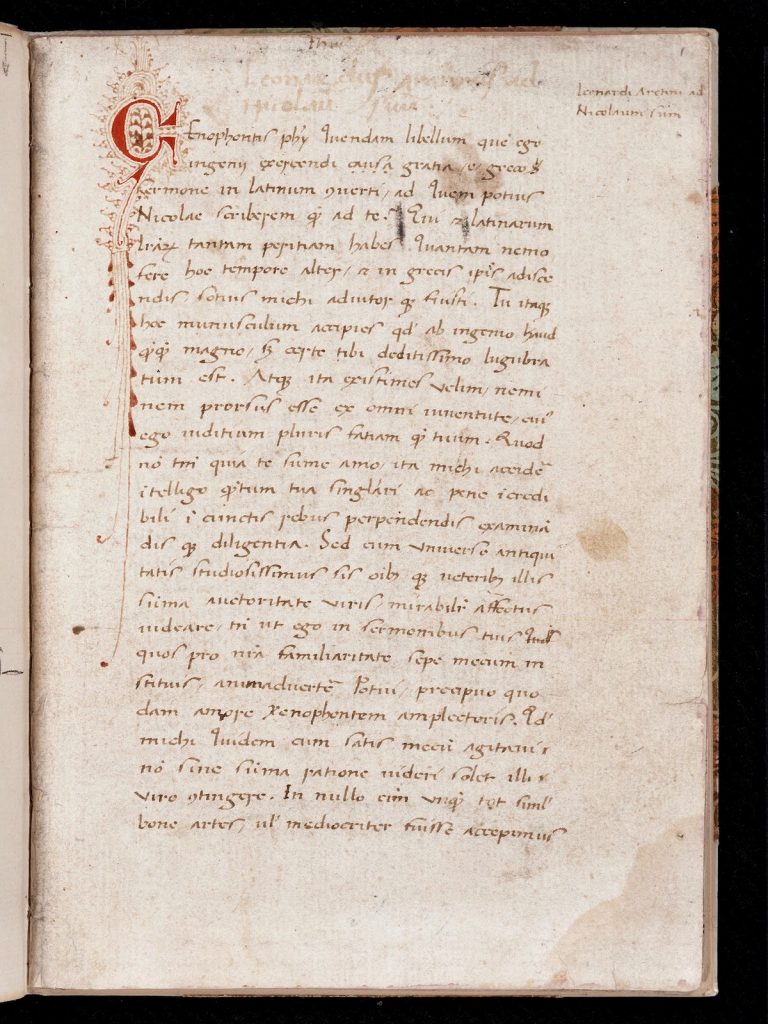

The Catálogo Colectivo de Marcas de Fuego is a fascinating resource for researching provenance and the movement of books in colonial Mexico and beyond. In order to encourage you to explore it (and marcas de fuego more generally) we share one final “snapshot” from Spencer’s collections — a photograph that we use on the page of our website that discusses Spencer’s Renaissance and Early Modern Imprints. Unlike the Advertenicas which was printed in Mexico City, the six volume Complutensian Polyglot Bible was printed in Spain under the patronage of Cardinal Francisco Ximenes de Cisneros in 1514-17, as noted in the volume (though actually, 1520/1521). However, at some point in the decades and centuries following its publication, Spencer’s copy travelled to “New Spain” and received its marcas de fuego. Can you identify whose heart-shaped brand this is? Take a look through the Catálogo Colectivo de Marcas de Fuego and then highlight the text in the square brackets to confirm your identification: [Convento de san Agustín (Puebla, Puebla), see for example the variations on the brand BJML-1005.]

![Marcas de fuego from the Convento de san Agustín (Puebla, Puebla) on Spencer Research Library's copy of Biblia polyglotta. Alcala de Henares: in Complutensi universitate, industria Arnaldi Gulielmi de Brocario, 1514-1517 [i.e. 1520 or 1521]. Call # Summerfield G41.](https://exhibits.lib.ku.edu/files/original/46c9f79ac0226357bb080b0e11e0f47d.jpg)

Both parts of Spencer’s copy of Advertencias para los confesores de los naturales by Fray Juan Bautista have been digitized and are available online (Images 1-370 are “Parte 1” and the binding of “Parte 2” begins at Image 371). You’ll also find a digitized copy of Spencer’s other “Mexican Incunable”– the 1571 edition of Alonso de Monlina Vocabulario en lengua Castellana y Mexicana (Call #: D214), a Nahuatl-Spanish dictionary–in our digital collections. To read more about both of these volumes, visit the online version of Spencer’s 2016 exhibition In the Shadow of Cortés: From Veracruz to Mexico City, where Caitlin Klepper discusses them in the section headed “The Colonization of This Land.”

- This blog post was originally intended to post in November 2020, but was postponed due to a time-sensitive post. Since then, a colleague at another university, Michael Taylor, has written a fascinating and more detailed post on marcas de fuego for the blog of the Book Club of Washington. Take a read to dive even further into the history and nature of these bibliographic firebrands.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian

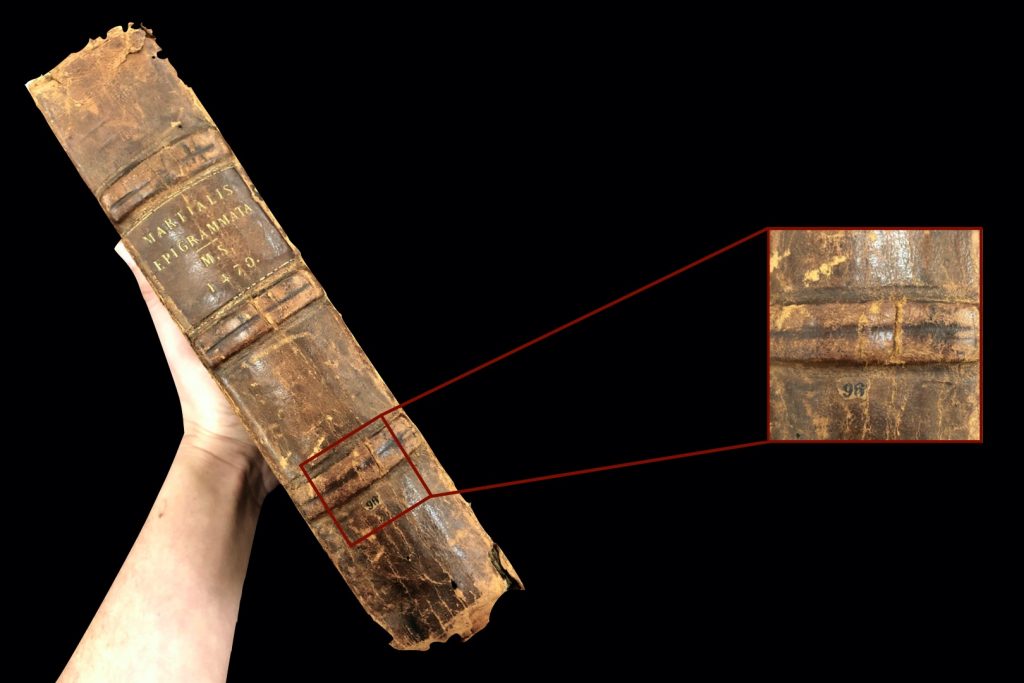

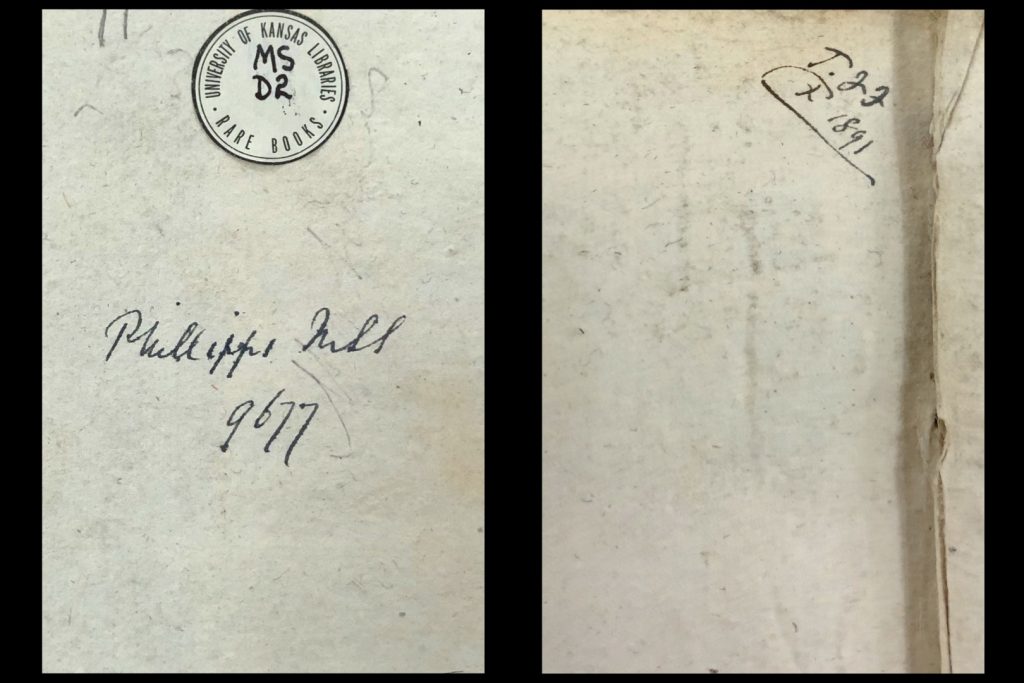

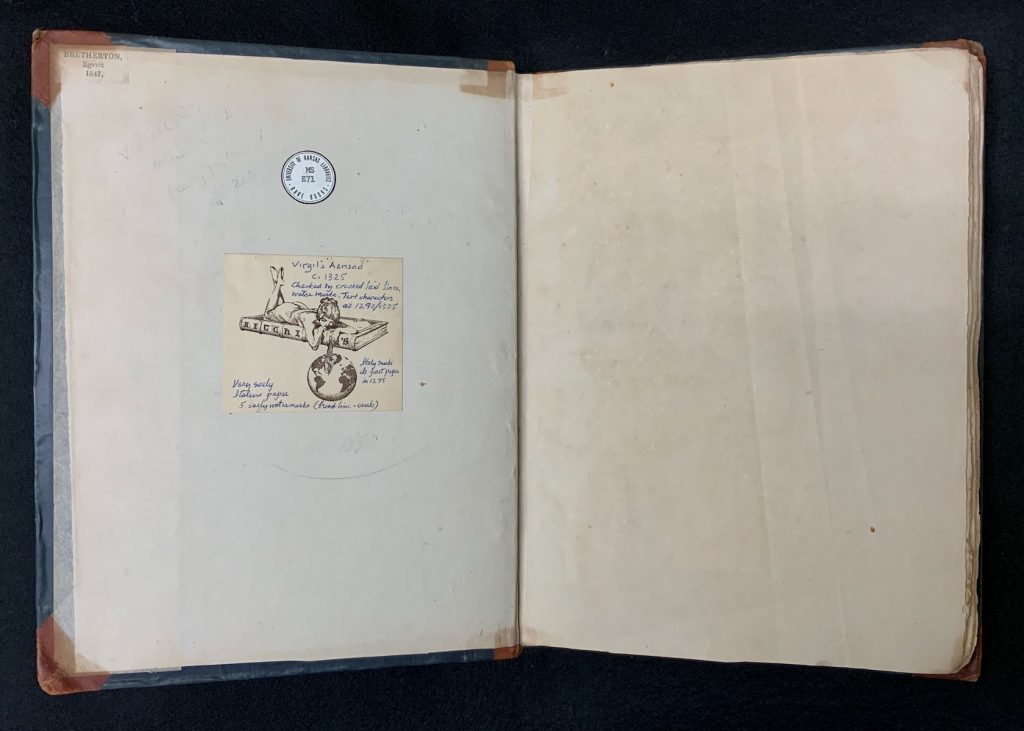

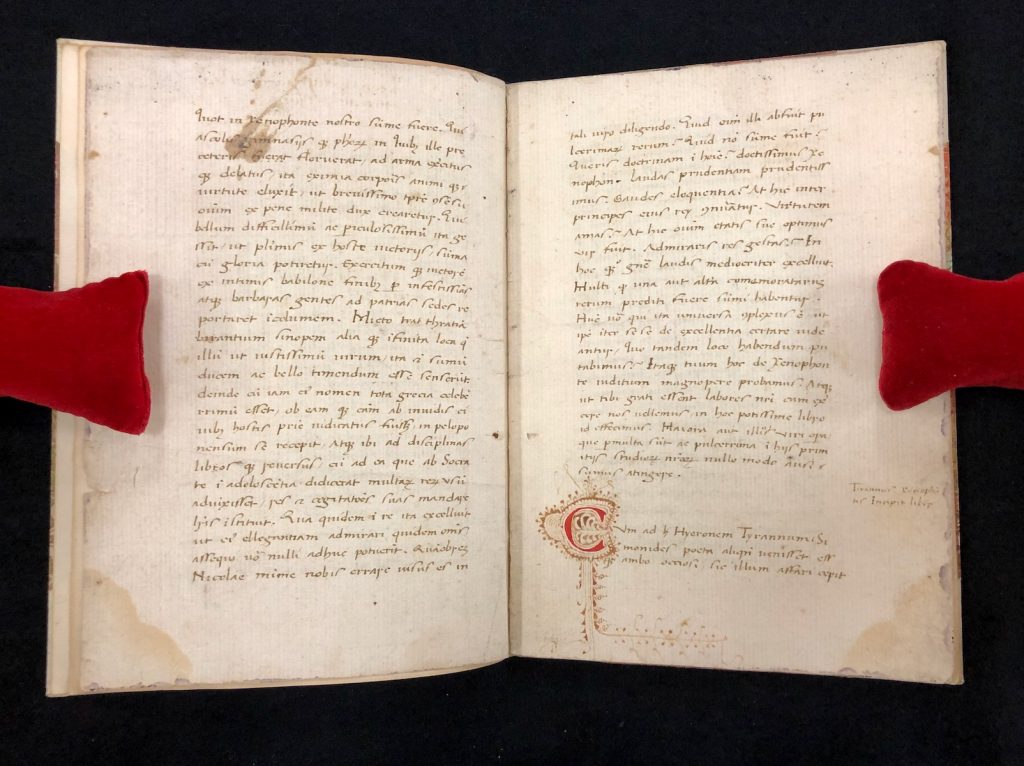

![Image showing the colophon in MS D2 on folio 184v, in which the scribe mentions their name (“Iacobus Tirabuschus B[er]gomensis”) and the date of the completion of the copying of the manuscript (“MoccccoLxxo die decimo nono Octobris”) in Martial, Epigrams, Italy (?), October 19, 1470. Call # MS D2.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/KSRL_MS_D2_folio_184v_detail-1024x683.jpeg)