Manuscript of the Month: From Genoa to Crimea, the Wide World of Books

August 25th, 2020N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

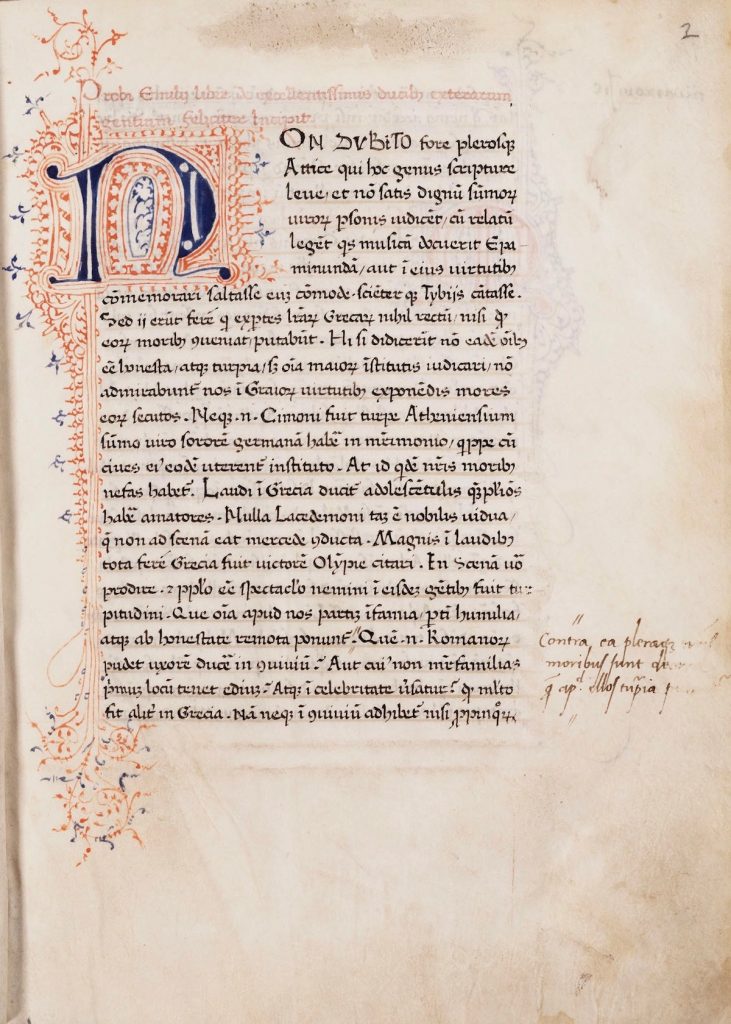

Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS C277 includes a translation from Greek into Latin of the Epistles of Phalaris by Francesco Griffolini of Arezzo (1420–1483?). Although throughout the medieval and the early modern period the letters were attributed to Phalaris, a tyrant who ruled in Sicily during the sixth century BCE, it is now believed that this was not the case, mostly thanks to the work of Richard Bentley (1662–1742). A scholar of Greek and Latin, Bentley was the keeper of the king’s libraries and later the master of Trinity College in Cambridge, UK. In the late 1690s, during a scholarly controversy following the appearance of the edition of the Epistles of Phalaris by Charles Boyle, fourth earl of Orrery (1676–1731) in 1695, which is now known as the “Phalaris controversy,” Bentley proved that the Epistles were not written by Phalaris but instead forged centuries later, perhaps as late as the fourth century CE.

The translation of the Epistles of Phalaris by Francesco Griffolini of Arezzo was the first translation of this work in Greek into Latin and is believed to be dated to the 1440s. The fifteenth century saw a great revival of the ancient and classical literature, especially in Italy, and a surge in translations from Greek into Latin. It is also known that Francesco Griffolini later produced a prose translation of Homer’s Odyssey in Latin at the request of Pope Pius II, as well as translations of the homilies of John Chrysostom among others.

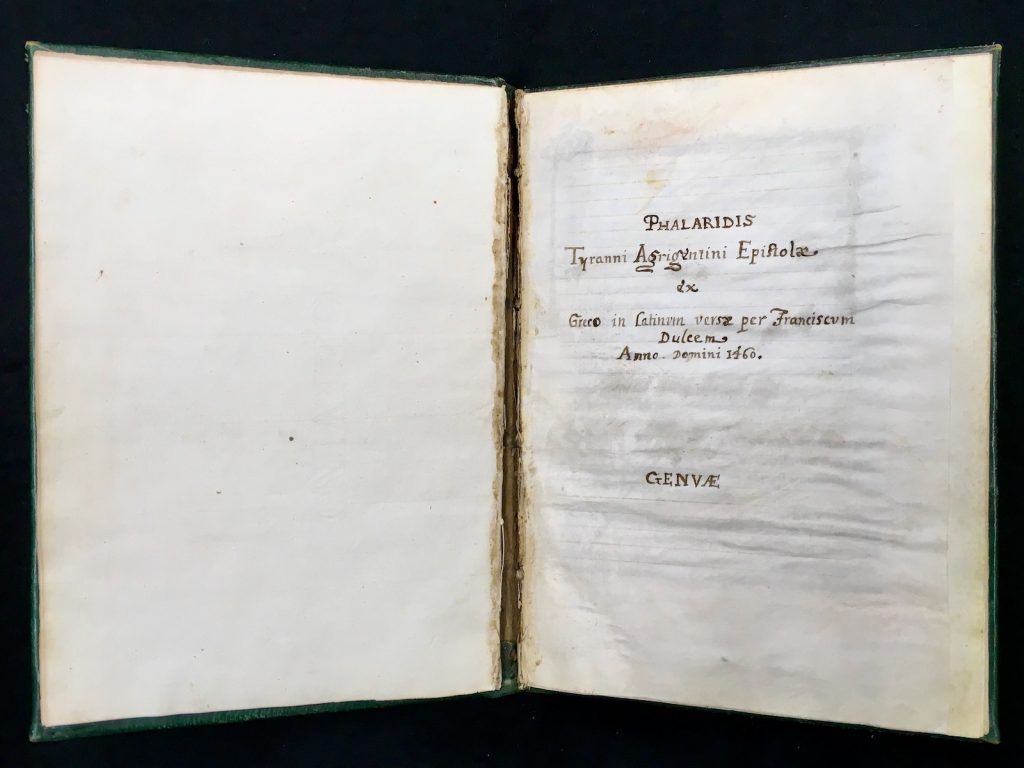

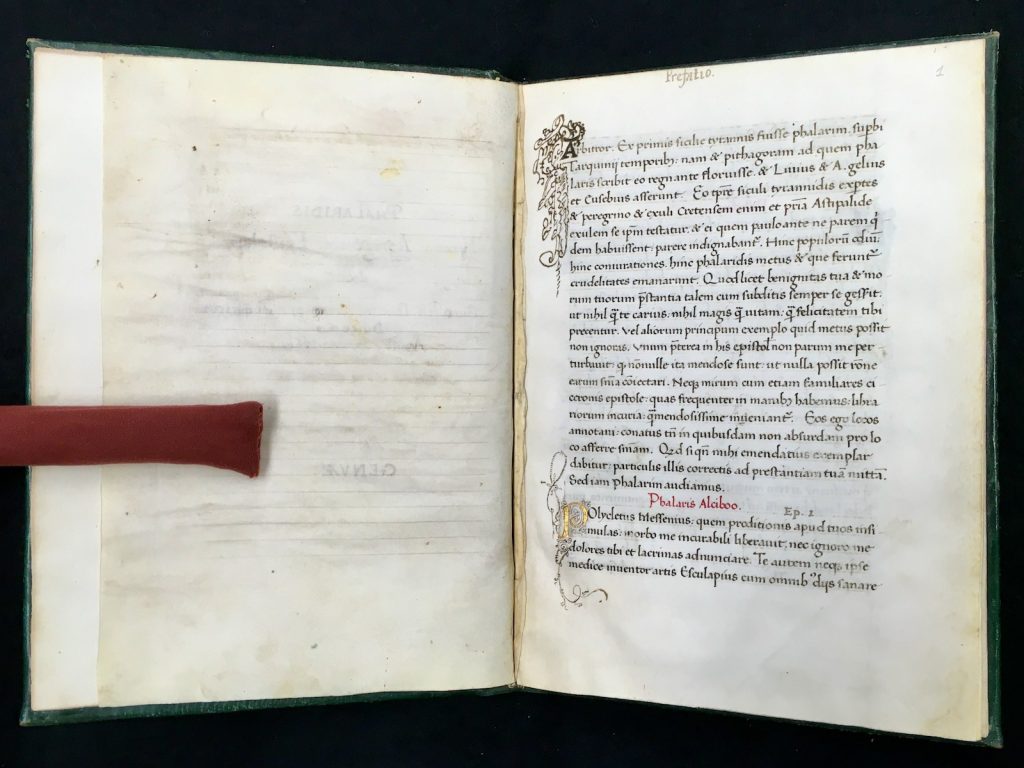

The translation of the Epistles of Phalaris by Francesco Griffolini is dedicated to Domenico Malatesta of Cesena, also known as Malatesta Novello (1418–1465), and opens with a dedicatory preface. As it stands, MS C277 is missing its first leaf and its second leaf is misbound and was placed as its final leaf at the end of the codex. Thus, the text begins in the middle of the preface, indeed in the middle of a sentence on what was originally the third folio of the manuscript. However, the first letter of the first word “arbitor” was later turned into a decorated initial in an effort to match the rest of the initials with penwork in the manuscript. The person responsible for this decorated initial A was probably the same person who added a title page to the manuscript to replace the leaf that had gone missing.

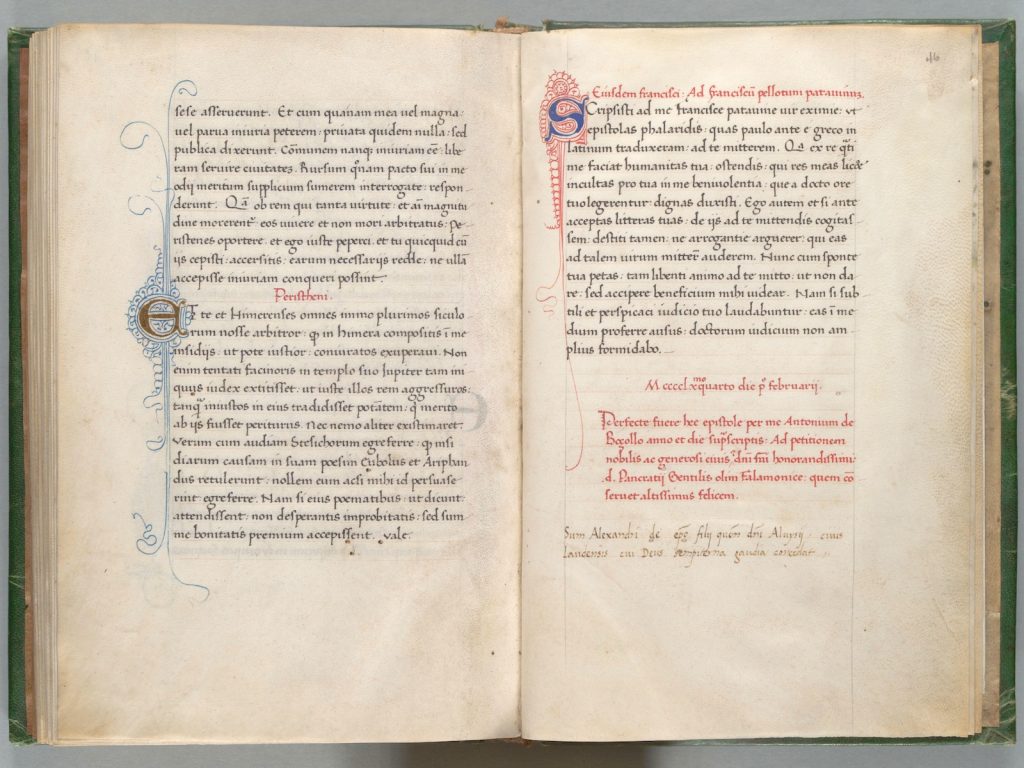

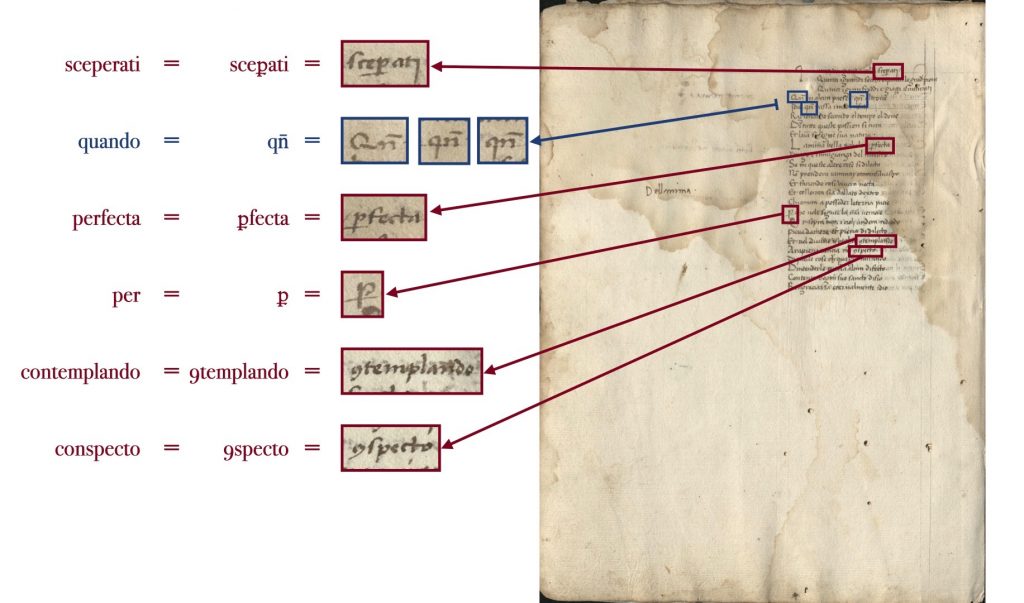

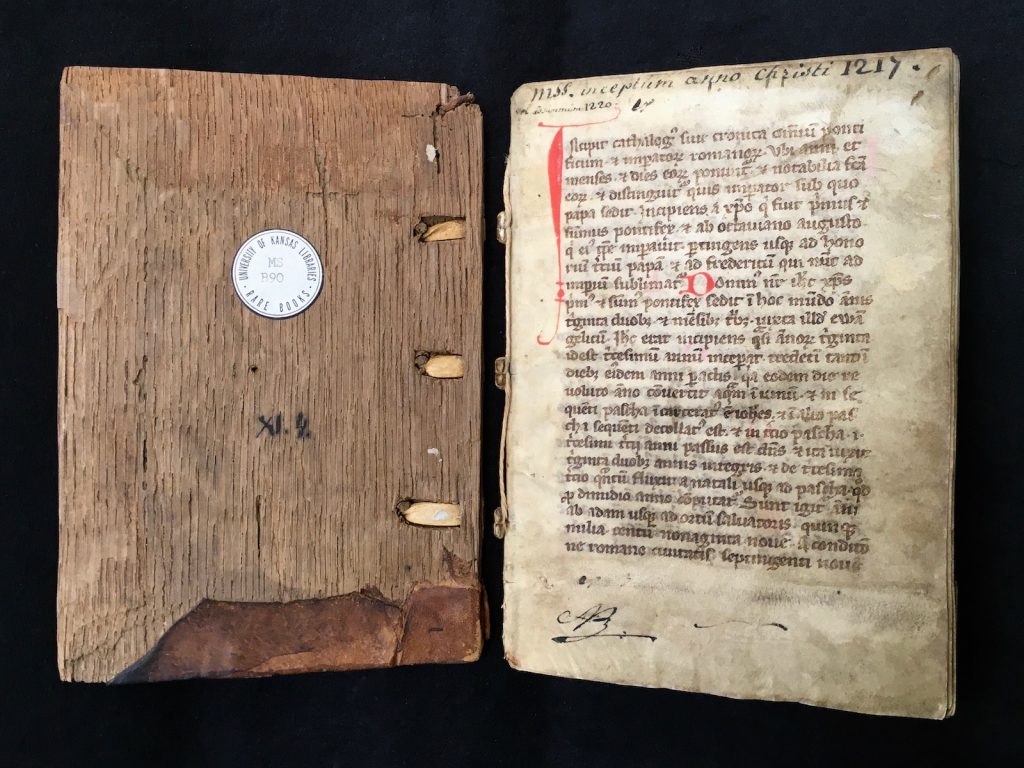

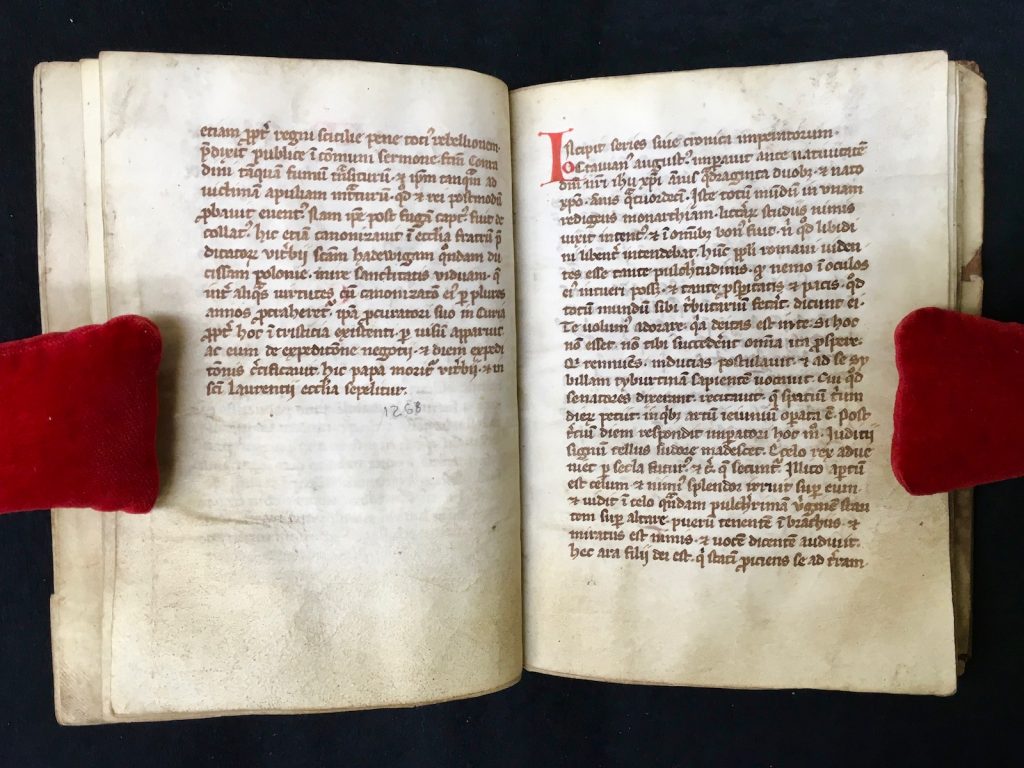

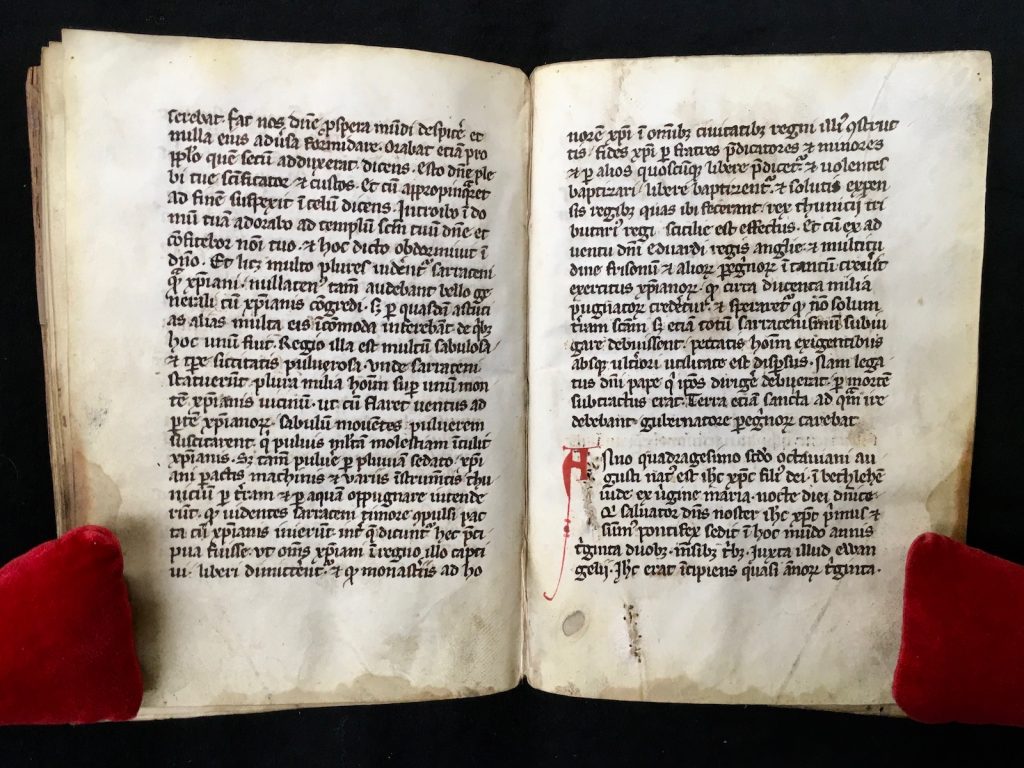

Some 150 copies of the translation of the Epistles of Phalaris by Francesco Griffolini survive in manuscript in addition to several print editions, the earliest of which is dated to 1468/1469. What sets MS C277 apart is that we know when and by whom the manuscript was copied. The information is relayed in a colophon at the end of the text: “Perfecte sunt per me Antonium de Boçollo notarium et in p[raese]ntiarum subcancellarium. Anno dominice nativitatis: MoccccoLxotercio die primo Iunii”: “These [letters] were completed by me, Antonius de Bozollo, notary and sub-chancellor at present, on the first of June in the 1463rd year of the birth of our Lord.”

We do not know much about Antonius de Bozollo other than what he professes in the colophon; that he was a notary and scribe, and at the time he was working for the Archbishop of Genoa, Paolo di Campofregoso (mentioned in the colophon as “P. […] Archiep[iscop]o Ianuen[si]”). Neither do we have any information about the early history of MS C277. It is plausible, however, that MS C277 was copied in or near Genoa. Indeed, it seems like the manuscript was not only copied there but remained in Genoa at least until the early nineteenth century. The watermarks on the paper flyleaves that were added to the manuscript with its latest and current binding were in use in the early nineteenth century in Genoa, and there are some notes in Italian in a modern hand about the contents of the manuscript on the front pastedown.

What is perhaps equally interesting is that the only other identifiable codex to be copied by Antonius de Bozollo is another copy of the Epistles of Phalaris. This manuscript is now San Francisco, State of California, Sutro Collection, MS 07, and it is also concluded with a colophon similar to that of MS C277. This time, the manuscript is dated to February 1, 1464, and was copied at the request of Pancratius Gentilis olim Falamonice, member of a Genoan family.

Based on the dates in the colophons, the two copies of the same text were copied by Antonius de Bozollo only eight months apart. Not only is the Humanistic script of the main text in both manuscripts very similar, but so are the manners in which the rubrics are inserted and the initials illuminated. This leads me to believe that Antonius de Bozollo was probably responsible for the entire production of the manuscript.

Other than MS C277 and Sutro Collection MS 07, which are definitely copied by the same Antonius de Bozollo, the Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts includes a Sotheby’s auction catalog record from June 1993 for another manuscript that seems to have been copied by an Antonio de Bozollo at the turn of the sixteenth century. In this case, not only is the suggested dating some 40 years later than these two manuscripts but also the current whereabouts of this manuscript is unknown, and therefore we cannot verify whether or not this Antonio de Bozollo is the same scribe as that of MS C277 and Sutro Collection MS 07. Or, it may be that the manuscript was simply misdated by the auctioneers and is actually to be dated rather earlier.

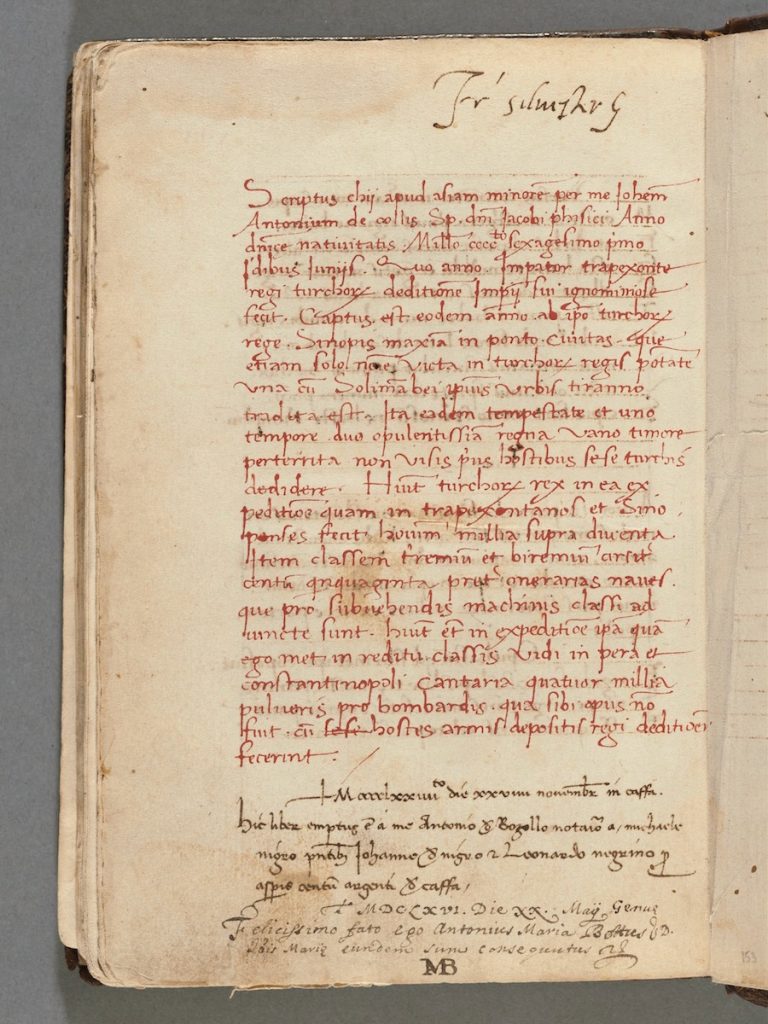

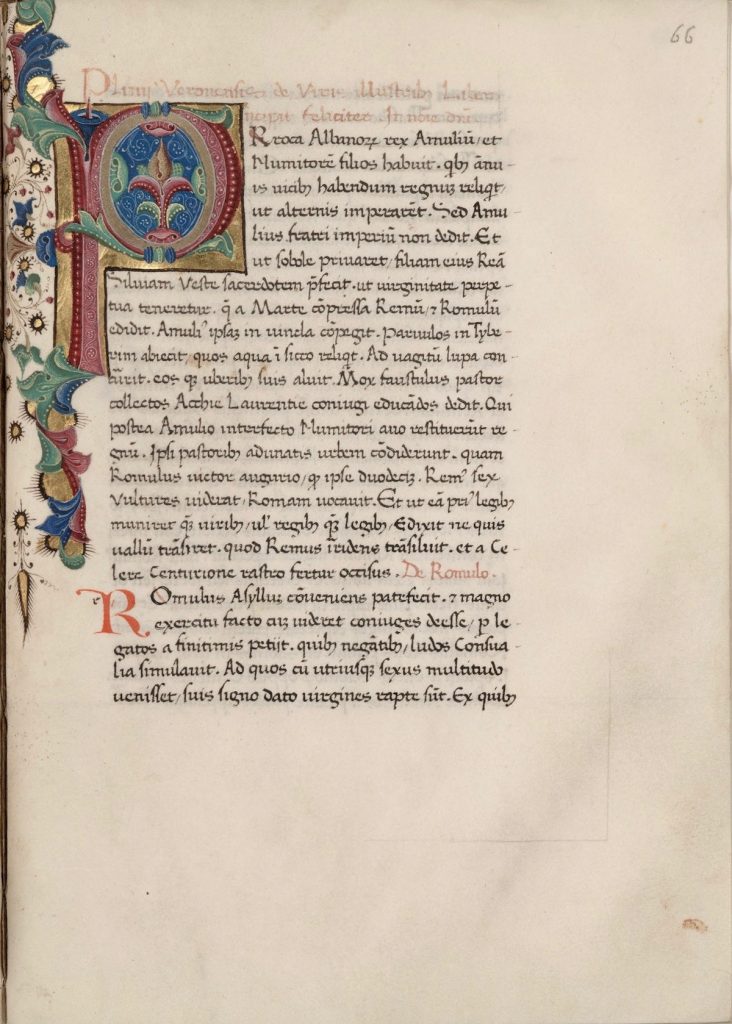

There is, however, another manuscript in which the name Antonius de Bozollo appears, but this time he is not the scribe but the owner. Harvard University, Houghton Library, MS Typ 17 contains a copy of Francesco Petrarca’s Africa copied by Giovanni Antonio de Colli on the island of Chios on the Aegean Sea and dated to June 13, 1461. Antonius de Bozollo has left an ownership inscription on the lower margin in black ink, just below the lengthy colophon, detailing his purchase of the manuscript. It begins with the date and place: November 28, 1474, Caffa (modern Feodosia in Crimea). It then reads that Antonius de Bozollo the notary purchased the book from Michael Niger for 100 silver aspers of Caffa. Those who witnessed the purchase are Iohannes de Niger and Leonardus Negrinus, who might have been related to the seller.

There are good reasons to think that the notary copying MS C277 in Genoa is the same person buying the book that was copied in Chios a decade later in Caffa. Indeed, we often forget how connected the medieval world was. The Republic of Genoa had a series of trading posts in the Mediterranean, the Aegean and the Black Seas. Indeed, outposts on the coast of the Black Sea existed since the second half of the thirteenth century, and until its incorporation into the Ottoman Empire in 1475, Caffa on the southern coast of Crimea was a prominent Genoese trade center. Similarly, Chios on the Aegean Sea was under Genoese rule from the beginning of the fourteenth century until its incorporation into the Ottoman Empire in 1566. This allows us to explain how a book that was produced in Chios ended up being sold in Caffa in less than a decade. It might also explain how a Genoan notary ended up in Crimea. The name of Antonius de Bozollo also appears in a series of records of the Bank of Saint George (also known as Ufficio di San Giorgio), a financial institution of the Republic of Genoa, in the years 1473 and 1474. One of these documents is from Caffa and is dated 1474.

The more that significant information such as the names of scribes and previous owners is recorded in catalogs, and the more that non-literary texts such as notarial documents are edited, the more we will be able to connect manuscripts and the producers and owners of these artifacts as well as the places that they have been. I would like to extend my gratitude to the late Bernard M. Rosenthal who had already pointed out the ownership inscription by Antonius de Bozollo in MS Typ 17 at the time of the sale of this manuscript to the Kenneth Spencer Research Library as well as Consuelo Dutschke who contacted us in December 2019 with the same information.

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from Bernard M. Rosenthal Inc. in 1994 (?), and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

![Image of a manuscript fragment (recto) possibly from Papias the Lombard’s Elementarium doctrinae rudimentum [Elementary Introduction to Learning]. France? Netherlands? 13th century? The fragment had been repurposed as the cover of a codex.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/01.-KSRL_MS-9-2-16_folio1r-1024x683.jpg)

![Image of a manuscript fragment (verso) possibly from Papias the Lombard’s Elementarium doctrinae rudimentum [Elementary Introduction to Learning]. France? Netherlands? 13th century? The fragment had been repurposed as the cover of a codex.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/02.-KSRL_MS-9-2-16_folio1v-1024x683.jpg)

![Image of a manuscript fragment possibly from Papias the Lombard’s Elementarium doctrinae rudimentum [Elementary Introduction to Learning]. France? Netherlands? 13th century?, digitally processed to enhance the legibility of water-damaged text.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/03.-KSRL_MS-9-2-16_folio1r_manipulated-1024x683.jpg)