Irish Ephemera for St. Patrick’s Day

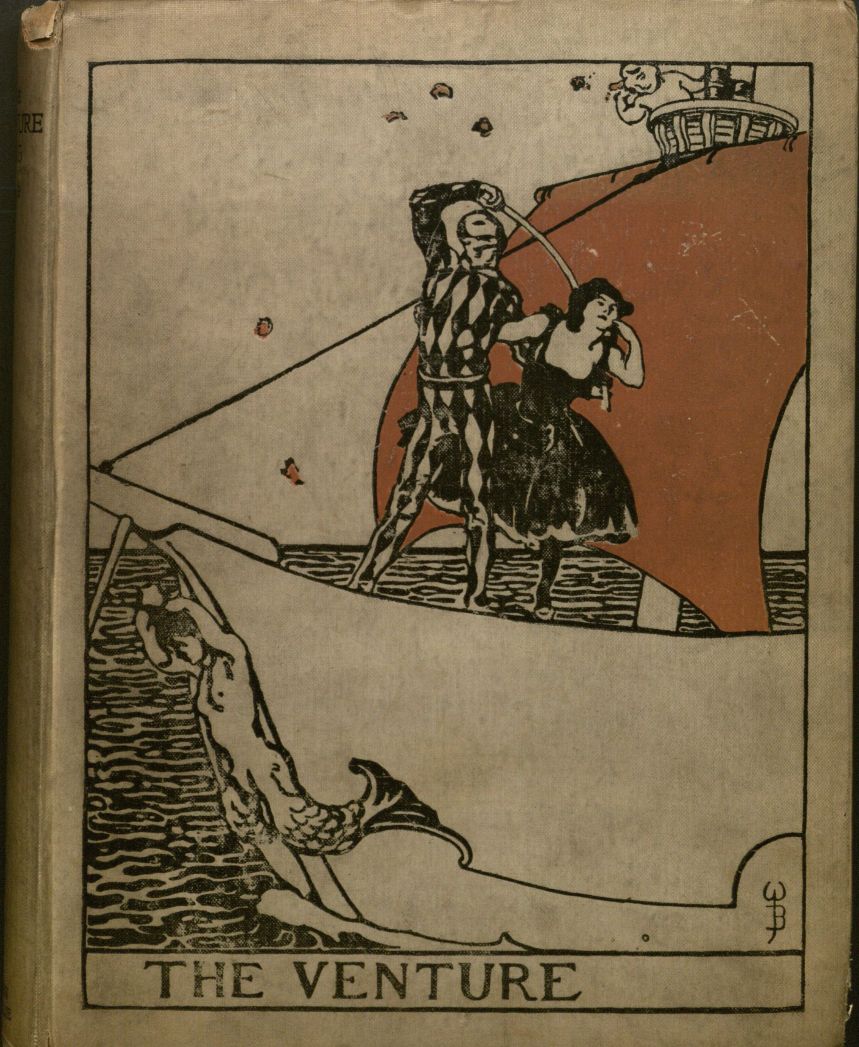

March 14th, 2014Some things are built to last, and others…well…are not. In honor of St. Patrick’s Day (this upcoming Monday), we are sharing five examples of ephemera from Spencer’s Irish Collections. “Ephemera” is the term applied to a variety of everyday documents originally intended for one-time or short-term use, including posters, playbills, political pamphlets, broadsides, advertisements, and newspapers (to name but a few). Such materials form the background of everyday life and furnish researchers with important information about the material, political, and cultural conditions of the past. Since Spencer’s Irish Collections include ephemera in addition to major works by significant authors, they serve as particularly fertile ground for students and scholars.

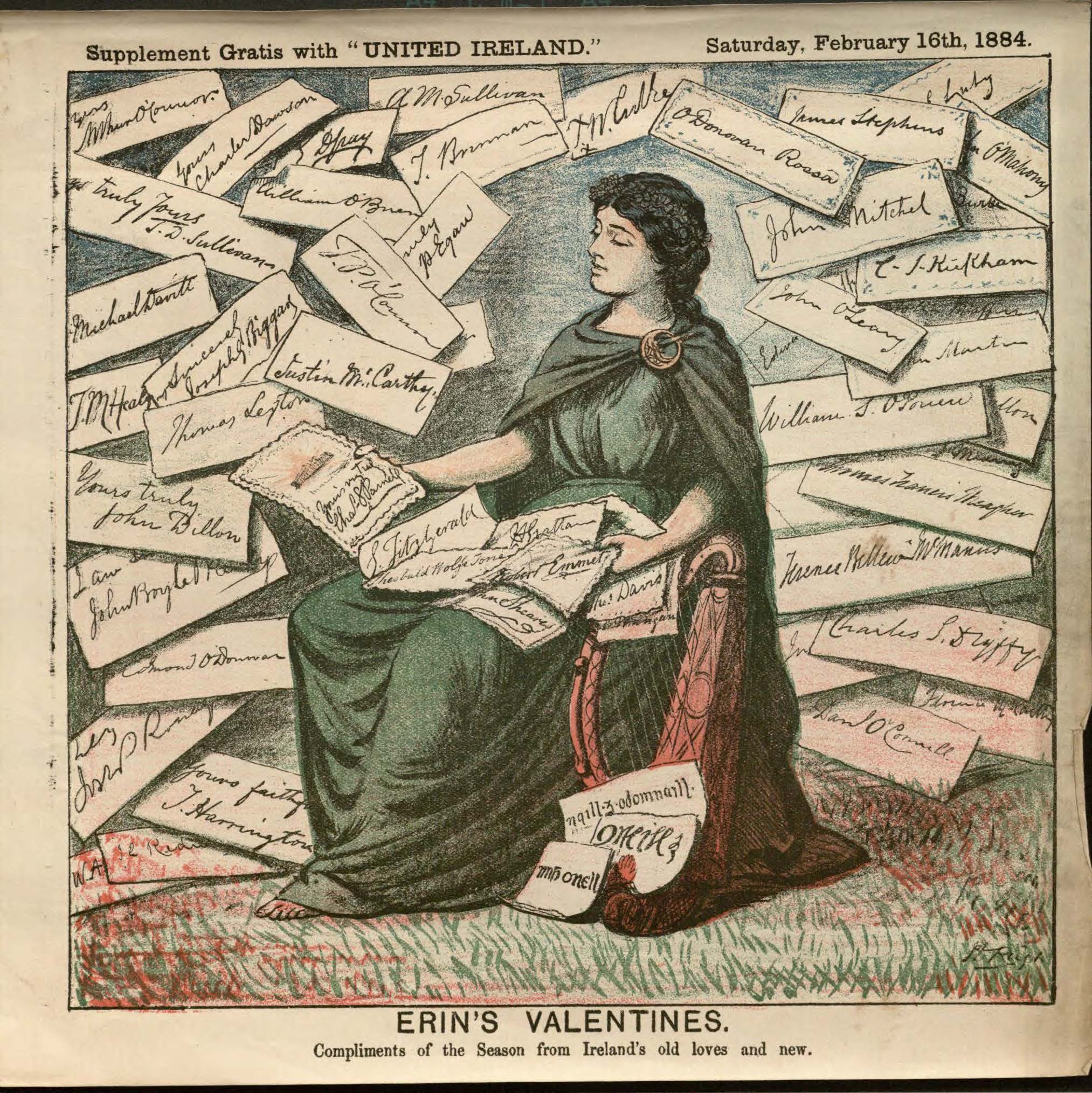

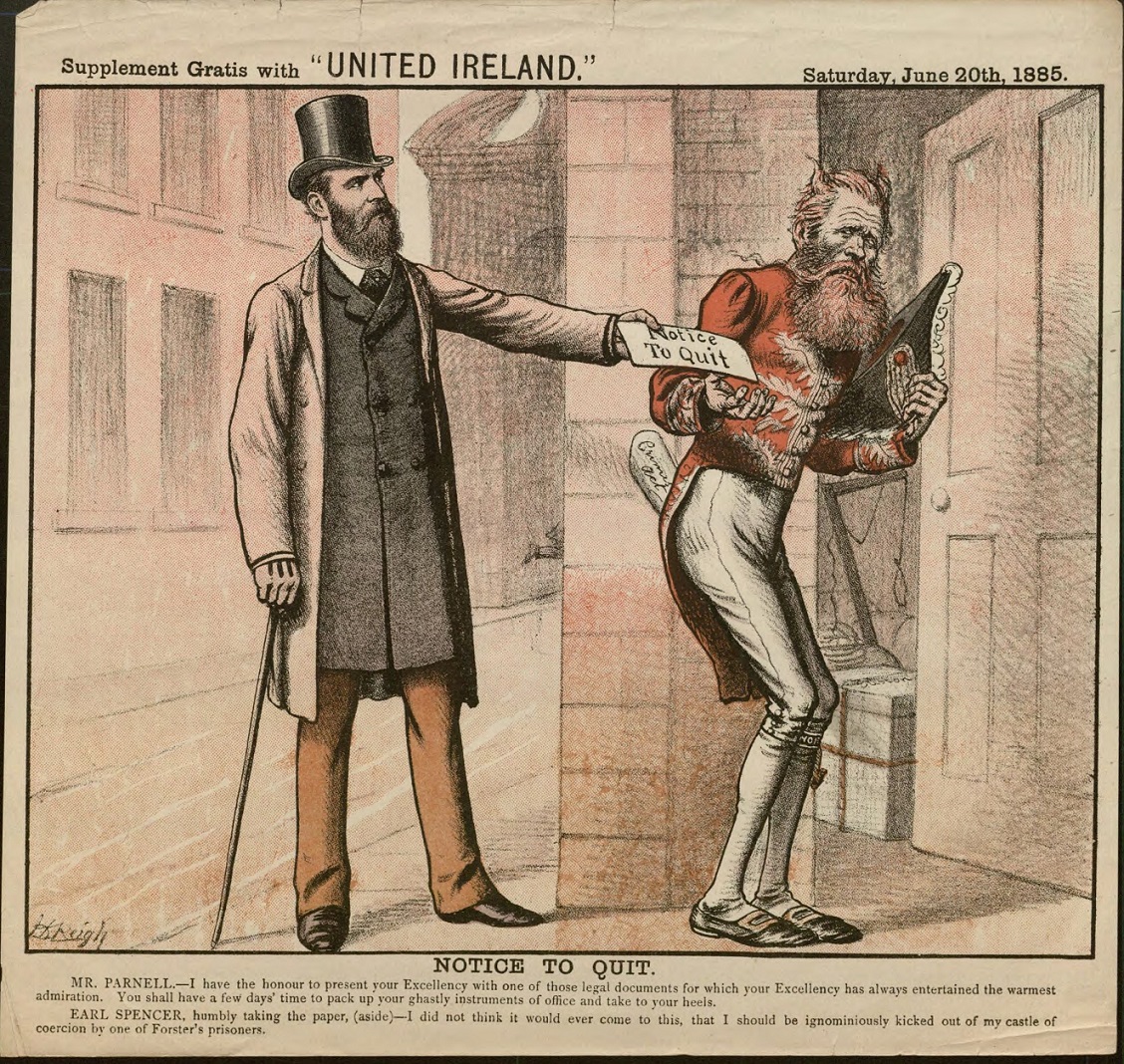

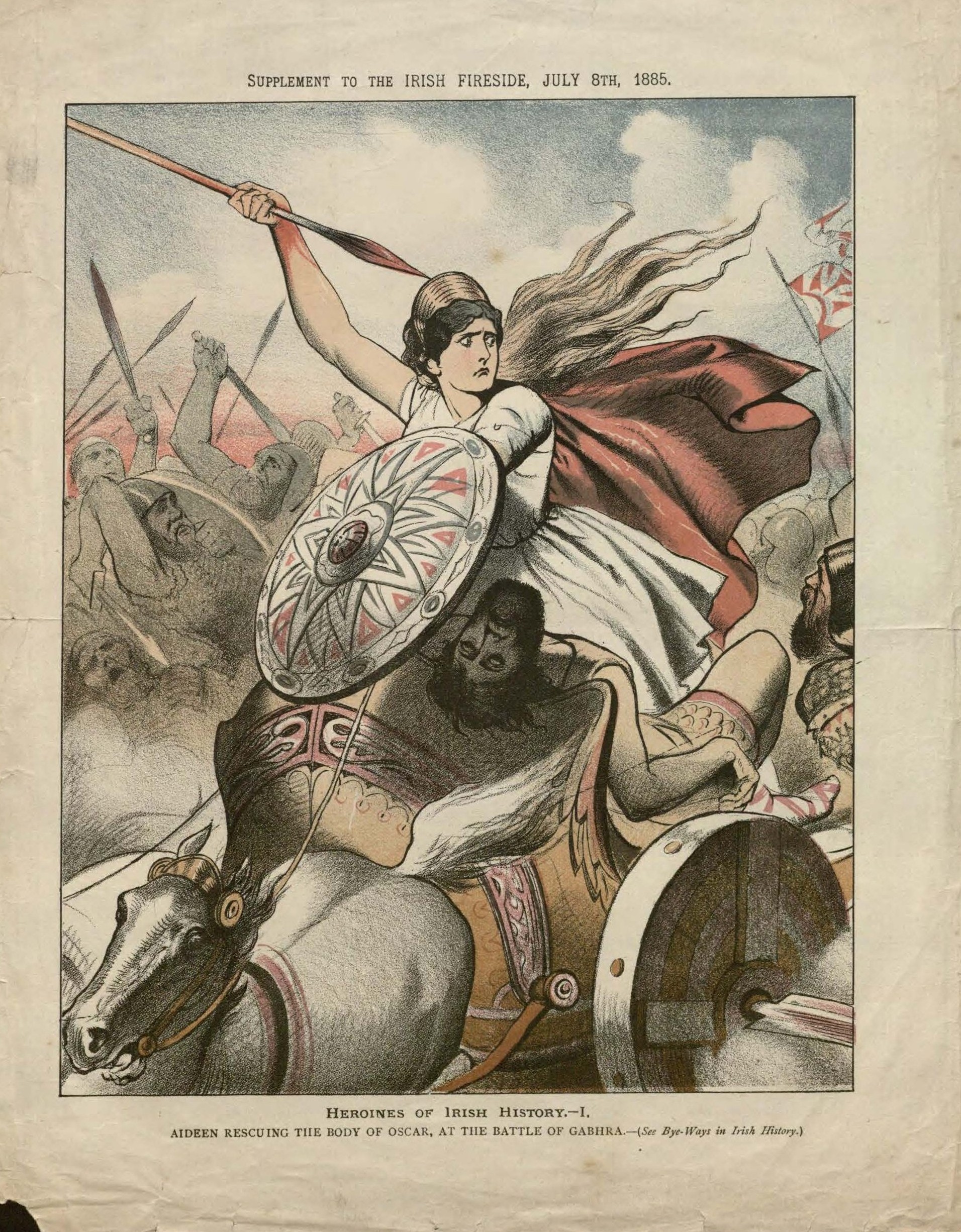

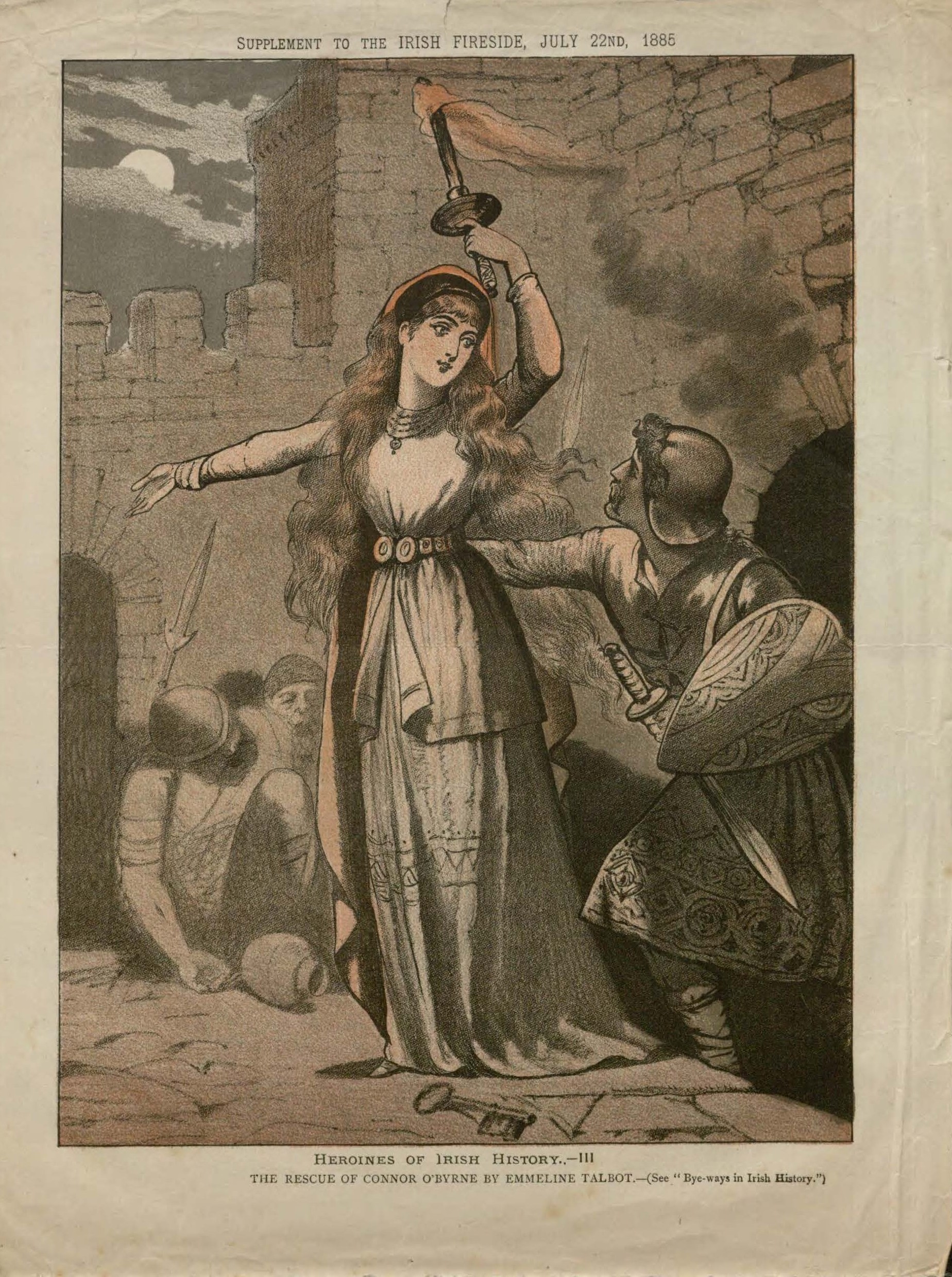

1. Color “Supplements” from United Ireland and The Irish Fireside, 1884-1885.

These colorful cartoons and illustrations are examples of loose supplements that sometimes accompanied late nineteenth-century Irish periodicals. The first three cartoons are from United Ireland and reflect that weekly’s Parnellite politics. Earl Spencer (John Poyntz Spencer), then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, is depicted with his distinctive red hair twisted into horns. The third cartoon shows Charles Stewart Parnell, the Irish nationalist leader, handing Earl Spencer his walking papers following the fall of William Gladstone’s administration in June of 1885. The final two illustrations come from The Irish Fireside, a periodical whose subtitle spells out its mission: Fiction / Amusement / Instruction. These illustrations celebrate Aideen and Emmeline Talbot as part of a series depicting heroines of Irish history.

Above: Color Political Cartoons, “Supplement Gratis with ‘United Ireland.'” [Dublin]: [United Ireland], 1884-1885. Call Number: DK17, Folder 16. Below: Heroines of Irish History–Aideen and Emmeline Talbot, “Supplement to The Irish Fireside.” Dublin, [The Irish Fireside], 1885. Call Number: DK17, Folder 5. Click images to enlarge.

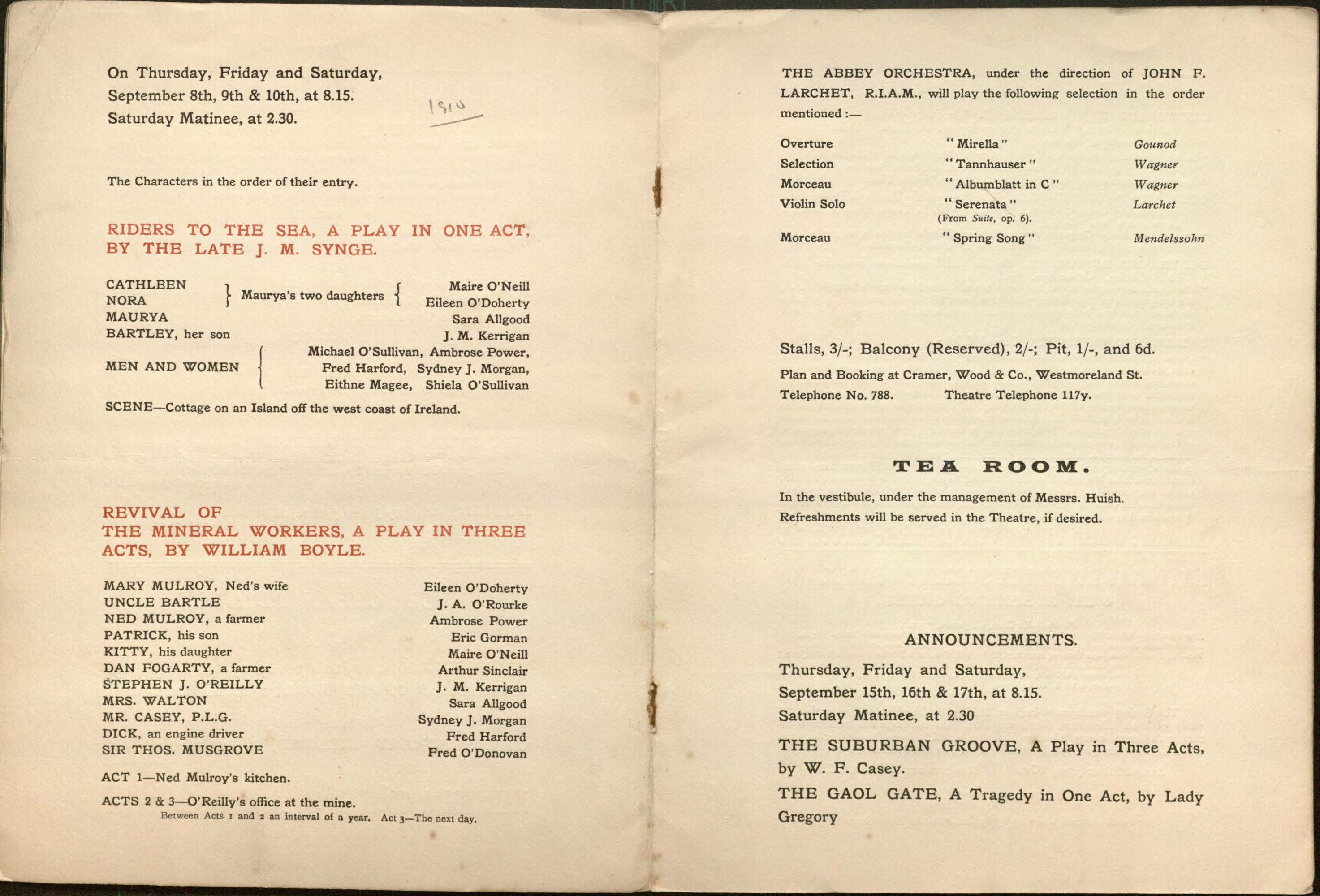

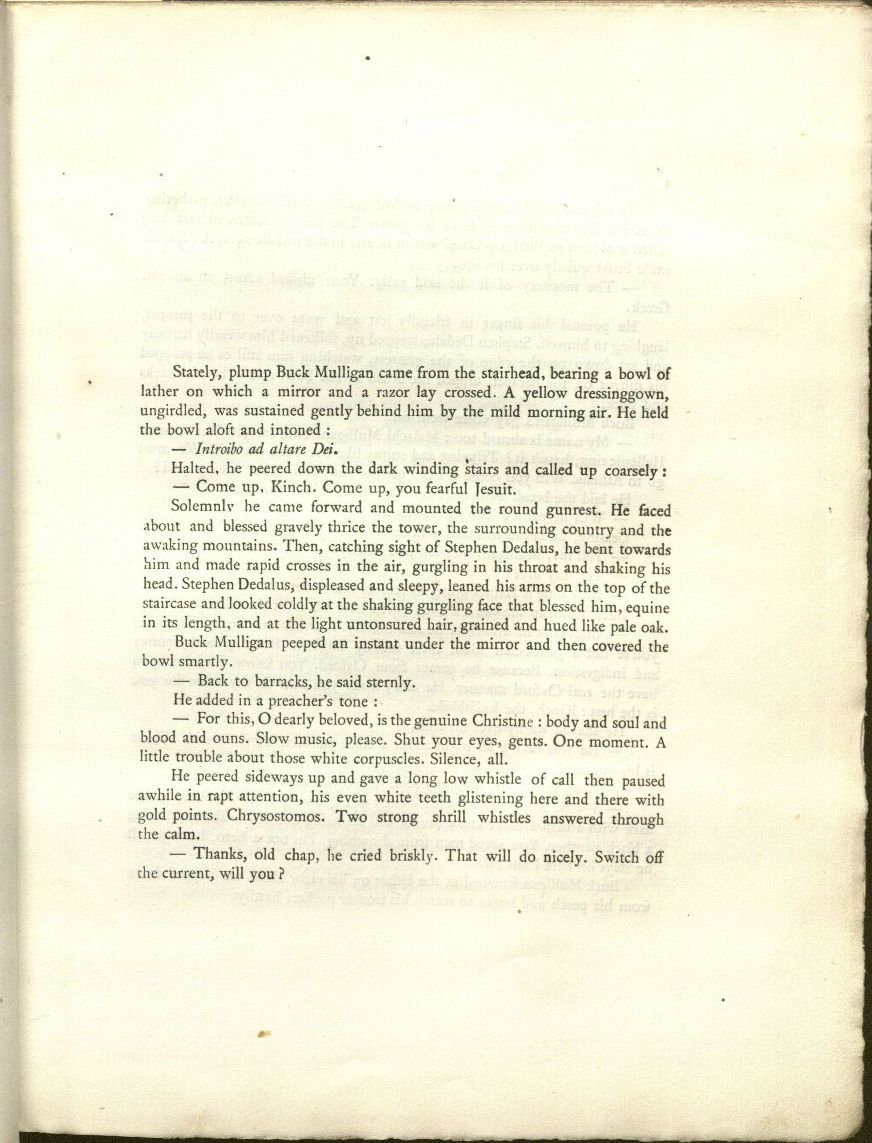

2. “Programme” for the Abbey Theatre, [1910]

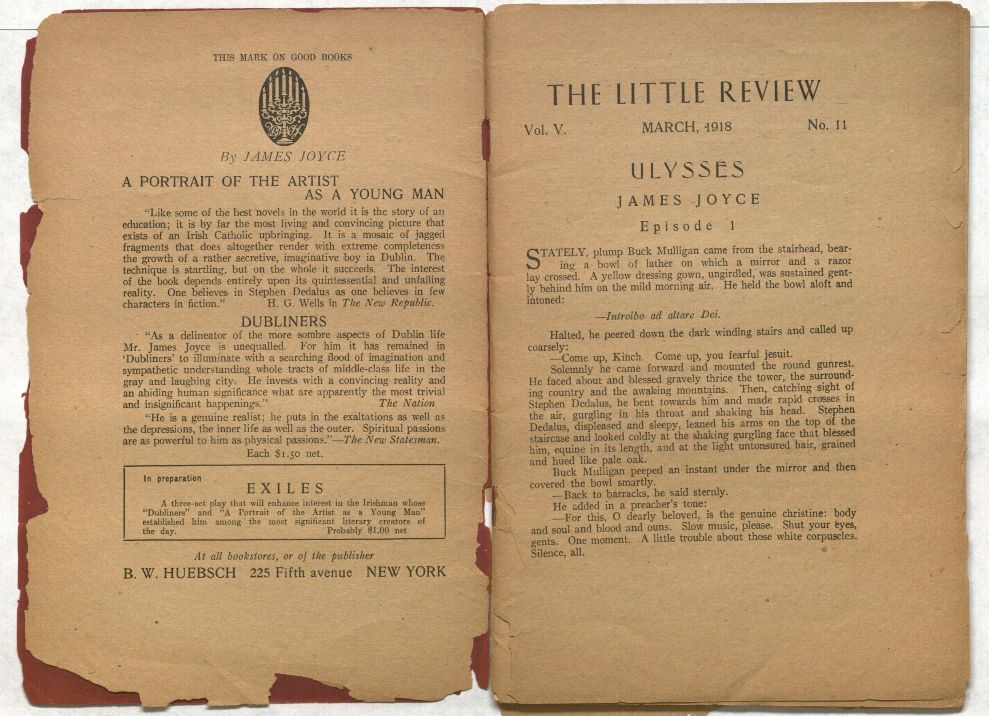

The Abbey Theatre was a key site for the Irish Literary Revival at the beginning of the twentieth century. W. B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, and (as seen below) J. M. Synge were among the playwrights active there. The Abbey Theatre’s printed programs record not only the dates of performances and the actors who played each role, but they also shed light on local businesses through the advertisements that appeared in their pages. Moreover, if you examine the ads closely, you’ll discover little gems, such as this 1910 announcement for James Joyce’s Dubliners by publisher Maunsel & Co. (“Ready in September” it promises). As Joyceans know, this “Dublin” first edition of Dubliners never did come to pass. Following long delays at the publisher over concerns about potentially objectionable content, the printed sheets for the edition of 1000 copies were destroyed (burned!) by the printer in September 1912, after Joyce tried to retrieve them. Understandably bitter, the author left Ireland for good, and satirized the incident in his poem “Gas from a Burner.” Dubliners would not reach the shelves until 1914, when it was published by the London firm Grant Richards.

Abbey Theatre, “Programme.” Dublin, [1910]. Call Number: D134, vol. 194. Click images to enlarge.

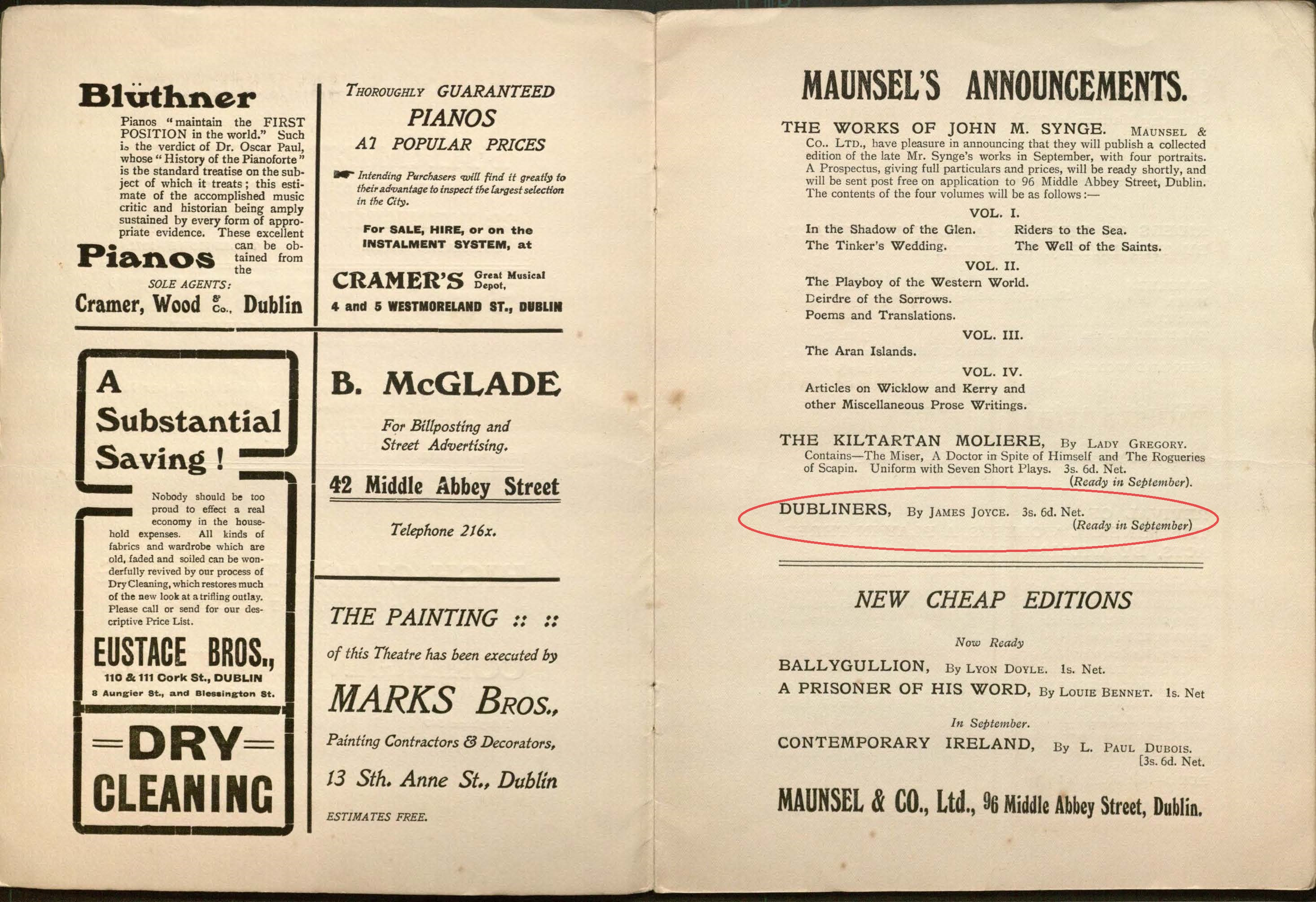

3. Gaelic League Carnival Poster, 1912

The Gaelic League was founded in 1893 to revive the Irish language, which was falling increasingly out of use, especially in urban areas where English was dominant. The majority of its members were middle- and working-class English-speakers, and by 1908 it boasted roughly 600 branches, primarily in cities. One of the ways that the organization attracted new members was by offering opportunities for socializing and fun alongside Irish language study. An tOireachtas, the annual national festival (also advertised below) was launched in 1897. As the poster notes, by 1912, there were even special excursion trains to carry visitors from Cork, Limerick, Galway, Belfast and other locales to the festivities in Dublin. After all, who can resist a hornpipe championship and £ 1,200 in prizes?

Gaelic League Carnival: Jones’ road, Dublin, … [June 29 to July 5, 1912]. Poster. Dublin: O’Loughlin, Murphy & Boland, Ltd., [1912]. Call Number: O’Hegarty Q36. Click image to enlarge.

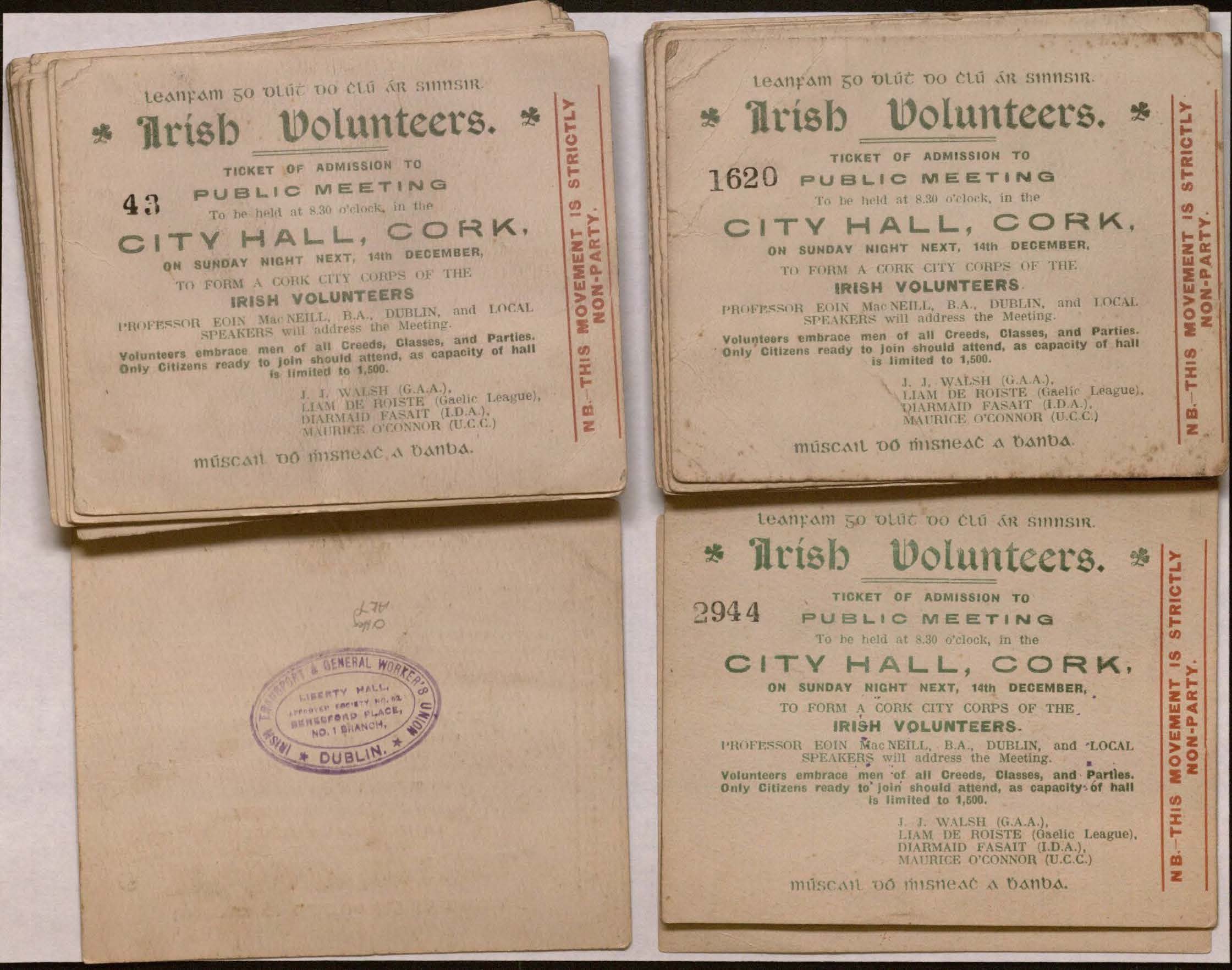

4. “Ticket of admission to public meeting […] to form a Cork City Corps of the Irish Volunteers,” [1913]

Eoin MacNeill, a founder of the Gaelic League, was also a leader of the Irish Volunteers, a paramilitary organization. As this ticket shows, MacNeill was to be the headliner at a recruitment event in Cork, held just a month after the group’s formation in November 1913. Spencer holds over 40 tickets for this event, several of which bear the stamp of the “Irish Transport and General Worker’s [sic] Union, Dublin” on the reverse. Interestingly, though the tickets themselves clearly state that capacity of the venue hall is limited to 1500, there are tickets in the lot numbered almost as high as 3000 (see below, bottom right).

“Ticket of admission to public meeting: to be held at 8.30 o’clock in the City Hall, Cork, on Sunday night next, 14th December, to form a Cork City Corps of the Irish Volunteers / Professor Eoin Mac Neill, B.A., Dublin, and local speakers will address the meeting. …” [Cork : s.n., 1913]. Call Number: O’Hegarty AK7. Click image to enlarge.

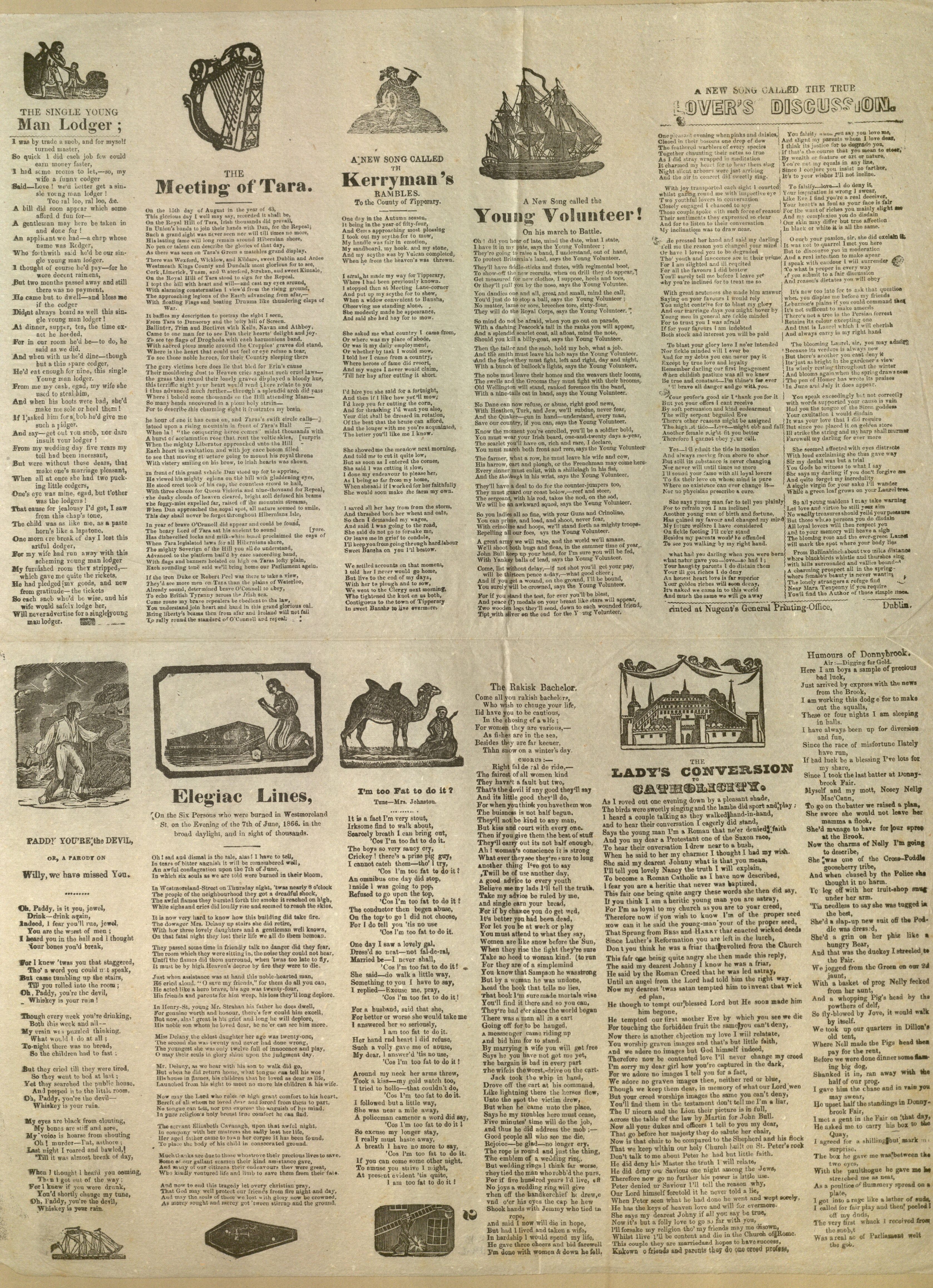

5. A sheet of “slip songs” from the mid-to-late 1800s

Ballads were popular street literature in Ireland, as in England. The earliest English printed broadside ballads can be traced back to sixteenth-century London; however the sheet pictured below was printed in Dublin during the second half of the nineteenth century. A large sheet like this would be cut up into slips by the printer or bookseller and sold individually, giving us the term “slip song.” Though often ornamented with woodcuts, these ballads and songs did not actually include music (only the occasional reference to a tune). Many of the songs on this particular sheet treat Irish themes, with the tone ranging from comic to satiric to elegiac to patriotic. History, politics, and love were all popular subjects, as were drinking songs and accounts of contemporary events, including crimes (“murder ballads”). Slip songs were meant to sell cheaply and quickly, so their paper tends to be thin and the printing rather shoddy. The staff at Nugent’s General Printing Office in Dublin must have been having a particularly bad day when they printed the sheet below. Skim through it and and you’ll find slanted text, uneven inking, inked “spaces,” and many, many typographical errors (we dare you to count the mistakes in “The Rakisk [sic] Bachelor”)!

Can you spot the typos? (hint: zoom in on the “Rakisk [sic] Bachelor,” to start…): Uncut sheet of Irish slip songs.

Dublin: Nugent’s General Printing Office, after 1866. Call Number: R43, Item 6. Please click to enlarge.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian