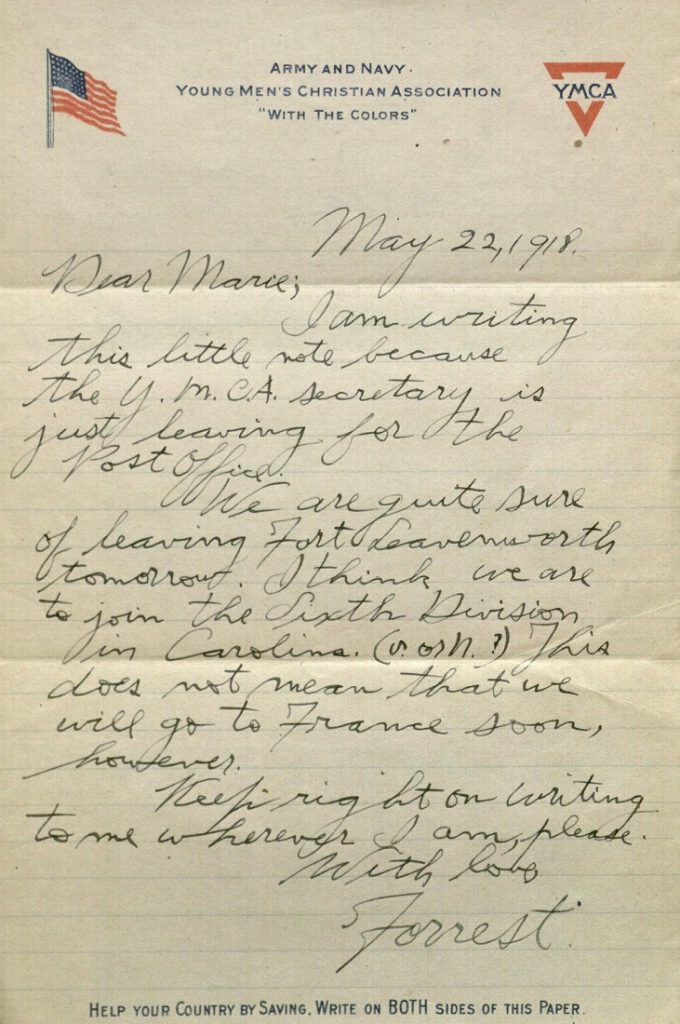

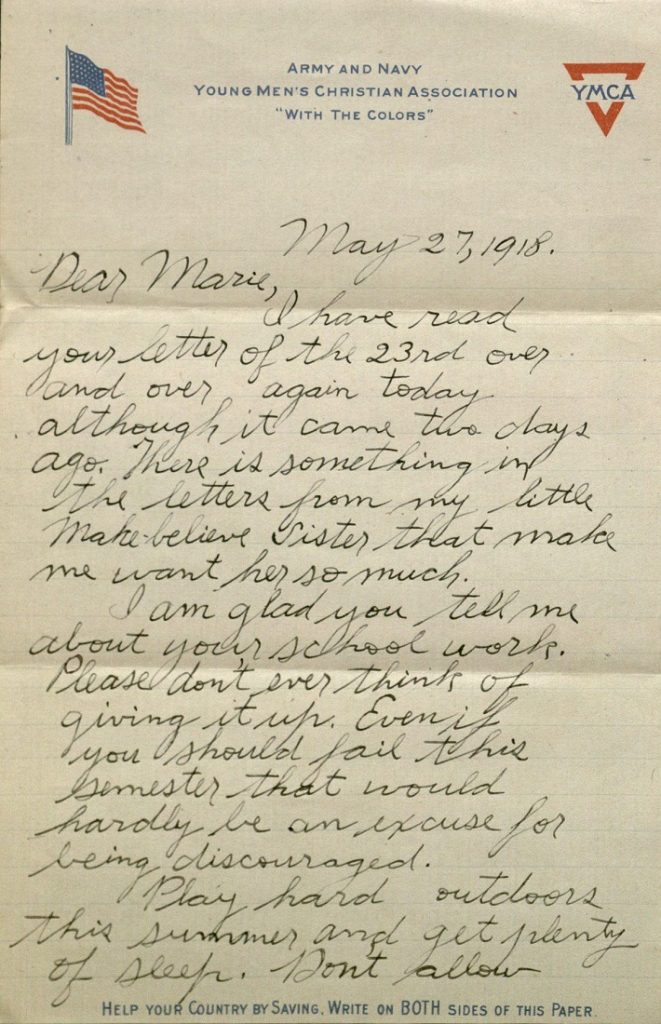

In honor of the centennial of World War I, we’re going to follow the experiences of one American soldier: nineteen-year-old Forrest W. Bassett, whose letters are held in Spencer’s Kansas Collection. Each Monday we’ll post a new entry, which will feature selected letters from Forrest to thirteen-year-old Ava Marie Shaw from that following week, one hundred years after he wrote them.

Forrest W. Bassett was born in Beloit, Wisconsin, on December 21, 1897 to Daniel F. and Ida V. Bassett. On July 20, 1917 he was sworn into military service at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri. Soon after, he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for training as a radio operator in Company A of the U. S. Signal Corps’ 6th Field Battalion.

Ava Marie Shaw was born in Chicago, Illinois, on October 12, 1903 to Robert and Esther Shaw. Both of Marie’s parents – and her three older siblings – were born in Wisconsin. By 1910 the family was living in Woodstock, Illinois, northwest of Chicago. By 1917 they were in Beloit.

Frequently mentioned in the letters are Forrest’s older half-sister Blanche Treadway (born 1883), who had married Arthur Poquette in 1904, and Marie’s older sister Ethel (born 1896).

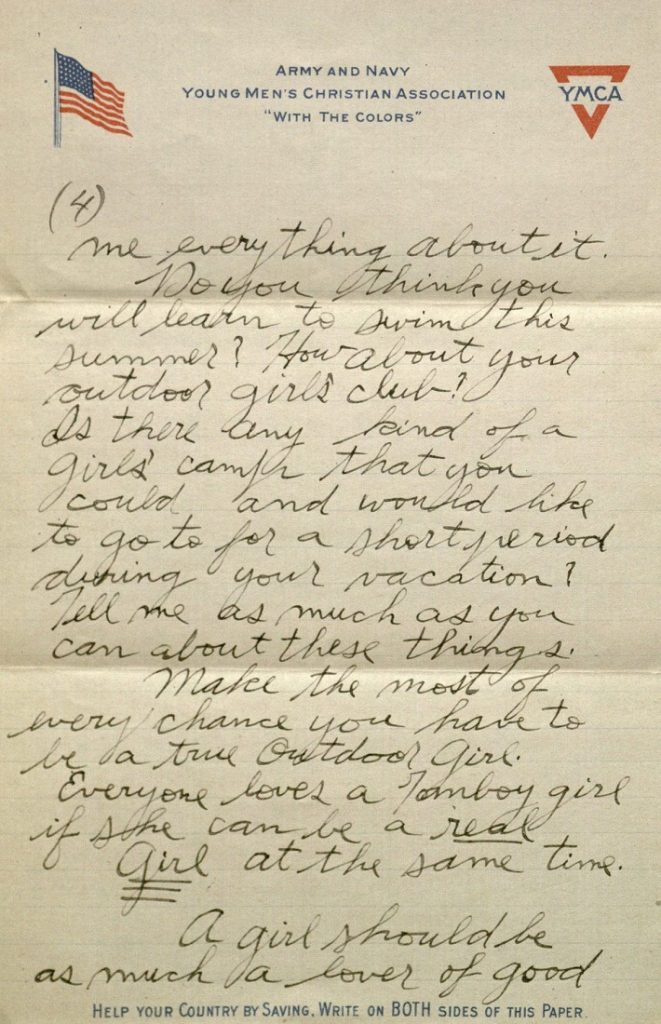

This week’s letters focus on telegraphy and Morse code, with Forrest sprinkling in news and advice to Marie: “whatever you do, you simply must get plenty of sleep“; “It would be fine if you could join an organization of real outdoor girls“; and “please be careful not to be too much in love with the Camp Grant boys because that sure would make me jealous.”

May 7, 1918.

Dear Marie,

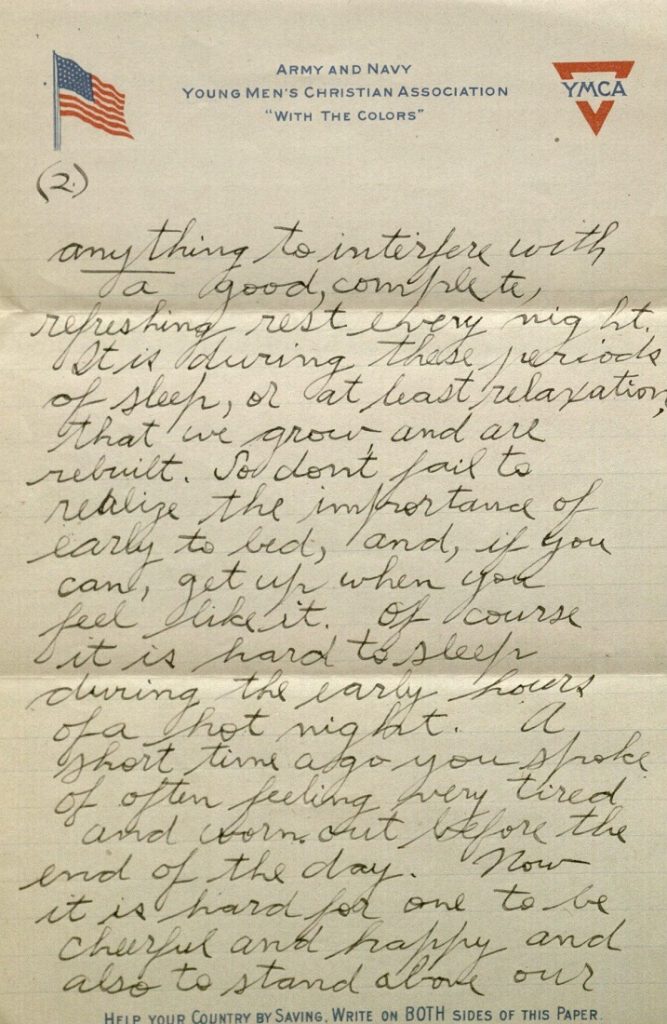

I sure did miss your letters but know you must be very busy, especially this part of the school term. That is one reason why I was afraid to interest you in telegraphy. Whatever you do, you simply must get plenty of sleep. Remember that nothing is so absolutely important as one’s physical health and I believe that in your case, the early to bed stunt is most necessary. So don’t you ever dare to write again and tell me that it is 10 or 10:30 P:M, and you aren’t in bed yet. Some time I will write you a letter about Physical Culture, but to tell the truth I still have hopes of seeing you again and it would be better for me to talk than write about it. However I want to say a few words about sour milk. The only difference between the sour milk I used to drink and common butter milk is that ordinary butter milk lacks the fat, or cream – which is not important. I wouldn’t bother to sour the whole-milk, but would prefer to buy the butter milk, unless the soured milk tasted better.

I am glad you decided to learn to telegraph. Do you want the key to stay on my desk and use it there, or would you rather have it on a table at 389 Highland? Be sure to tell me just what you want as I am sure Roy [likely Forrest’s older half-brother Roy Treadway, born 1879] would fix it for you if you want it moved. The main thing in fixing a key is to have it on a solid table of the same height as an ordinary writing table or desk. The key must be far enough forward to allow plenty of room for the elbow to rest on the table without being cramped in any way. Also, the key arm must be in a straight line with the operator’s forearm. The position of the arm, wrist, and fingers is the most important thing in telegraphy.

First – the elbow must be supported on the same board, on level with the key. The elbow must rest, without any strain or tension on the muscles of the upper arm or shoulder. Unless the muscles not moving the key knob are relaxed, one will get cramped and tired easily and pretty soon the sender is apt to be victum (?) to a nervous trouble known to telegraphers as “glass arm,” as the arm becomes stiff and uncontrollable.

Second – the position of wrist and fingers. This is perfectly described in the little Signal Drill book, page 321, paragraph 846. Every word in every sentence in # 846 ought to be underlined. Note the picture showing the hand on the key – the position of thum and forefinger, and the curve of the latter. Every time you touch the key knob copy this position faithfully. Also read paragraph 846 p. 321 each time. The quality of your sending will depend on the proper holding of the key knob, and the relaxation of the upper arm, every time. If you haven’t the drill book or can’t find the paragraphs I refer to let me know.

Paragraph 844 page 320 explains about spaces, etc.

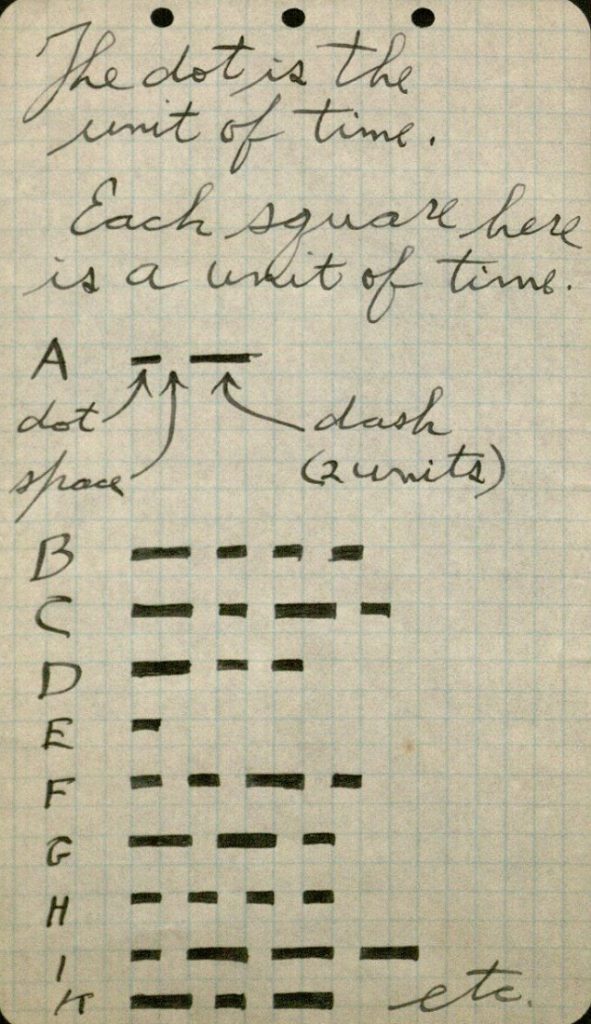

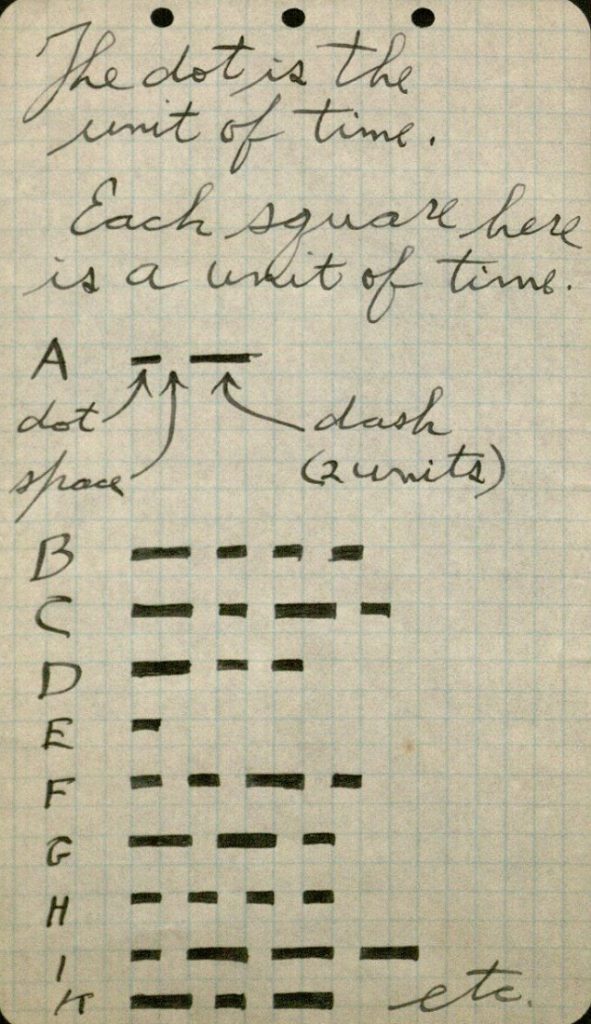

(1.) The dot is the unit of time.

(2.) – etc.

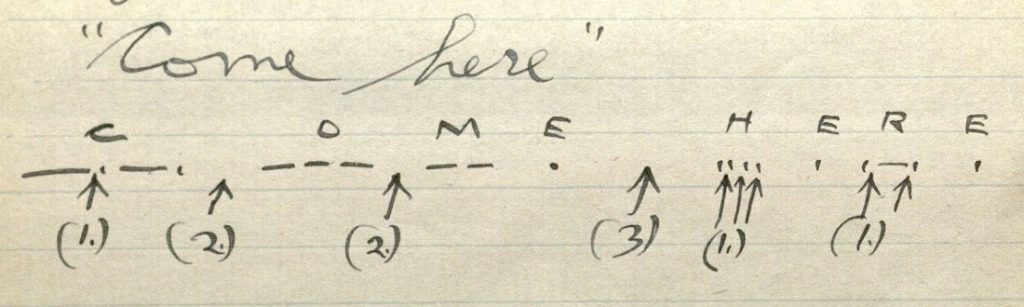

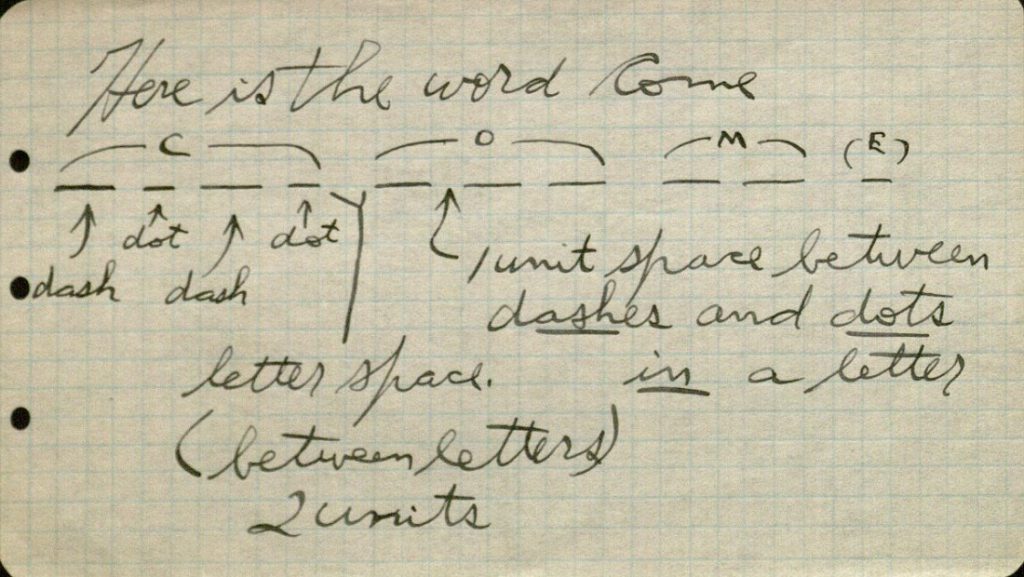

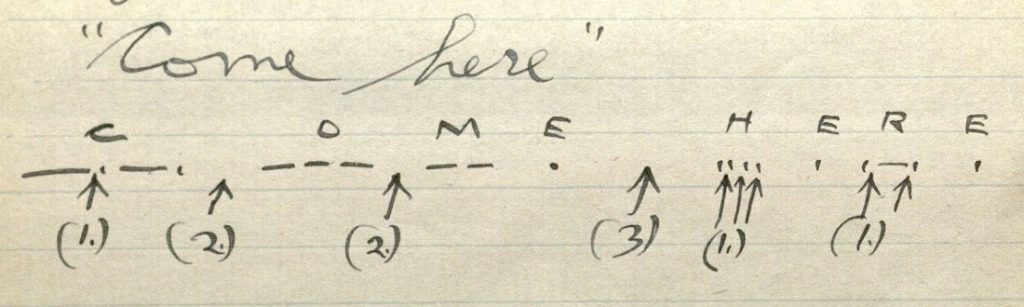

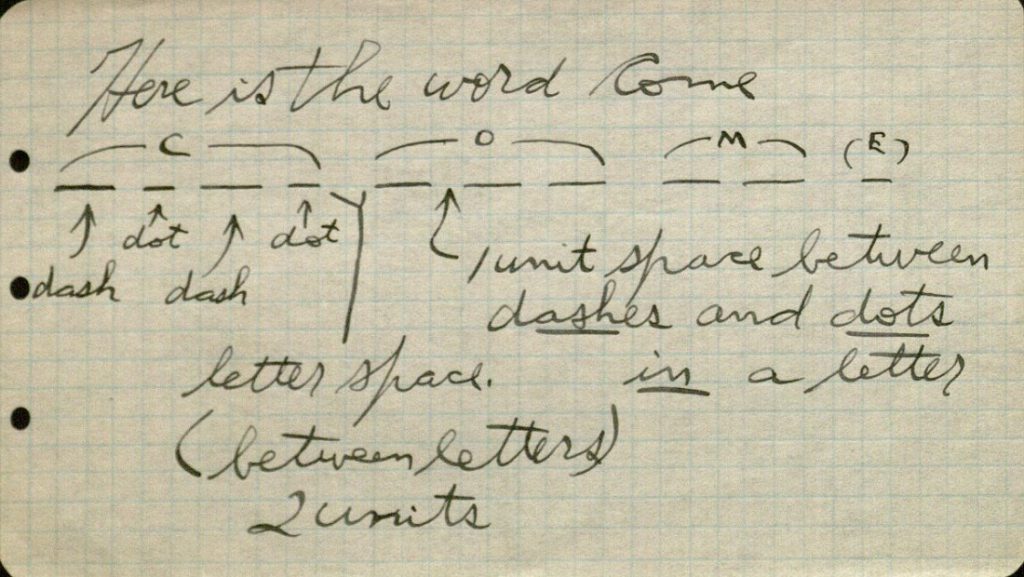

I have enclosed a sheet of cross ruled paper [see below] in which each square is a unit. There is no long dash in the radio code[.] It is impossible to make a dash exactly twice as long as a dot or a space between letters twice as long as a space between dashes and dots in a letter as I show on the word “come.” Better make it like this:

C o m e

_._. _ _ _ _ _ .

Letter space [marked with an arrow between C and O, above].

The letter space must be plenty long enough to thoroughly separate one letter from another.

The word space is longer than the letter space so as to set off each group of letters into words.

Click image to enlarge.

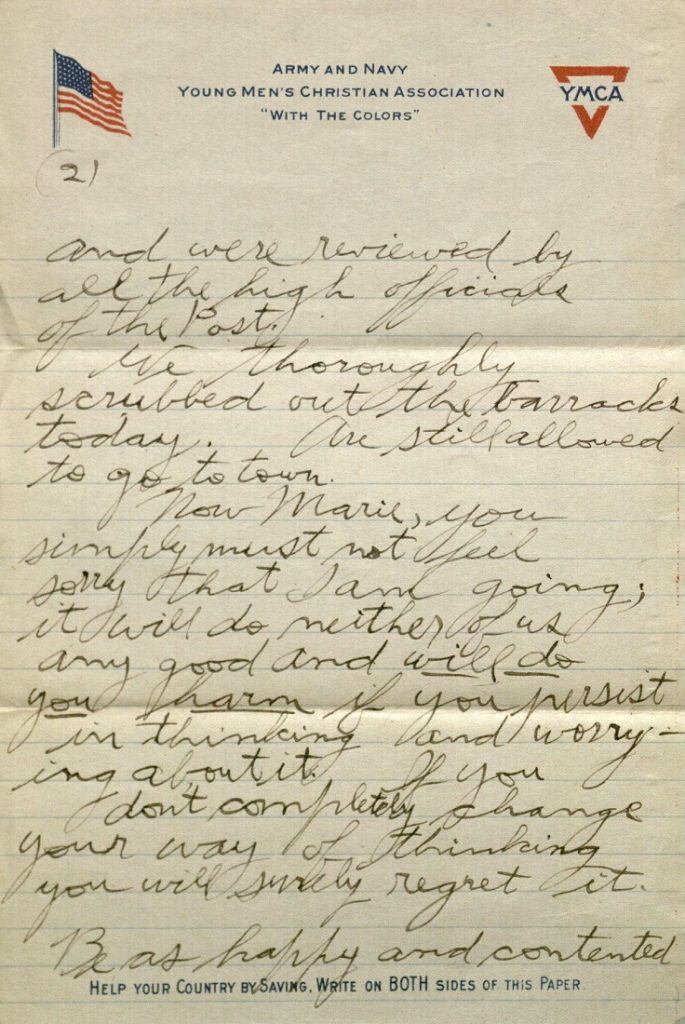

“Come Here”

C O M E H E R E

_._. _ _ _ _ _ . …. . ._. .

1 2 2 3 1 1

- Space between dots and dashes – as short as possible.

- Letter – space – much longer.

- Word – space – still longer.

So you see paragraph 844 is mostly theory.

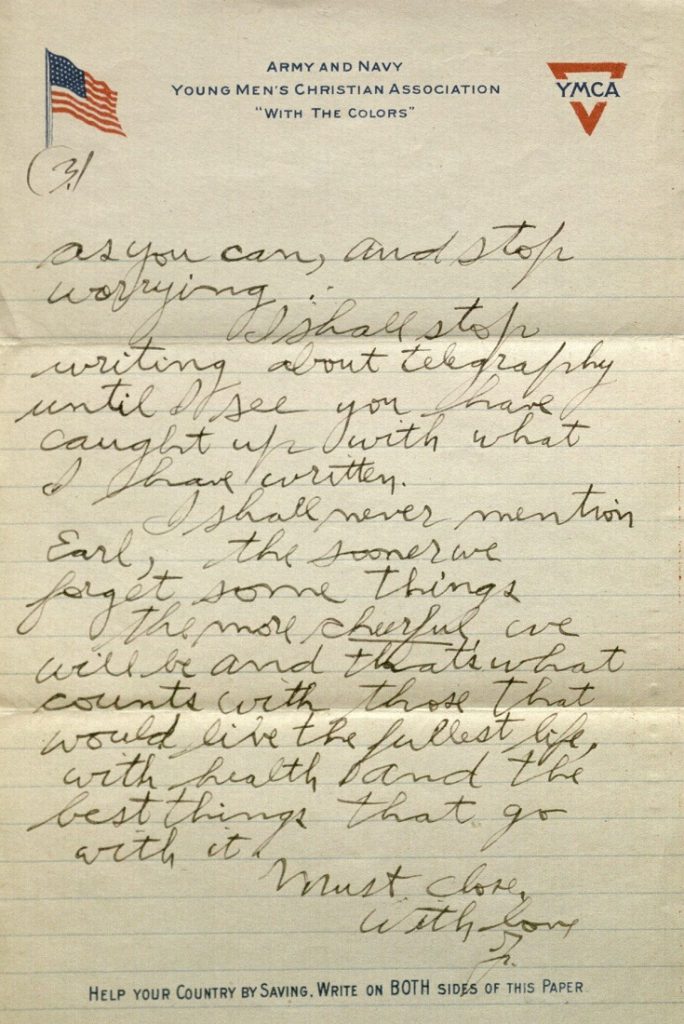

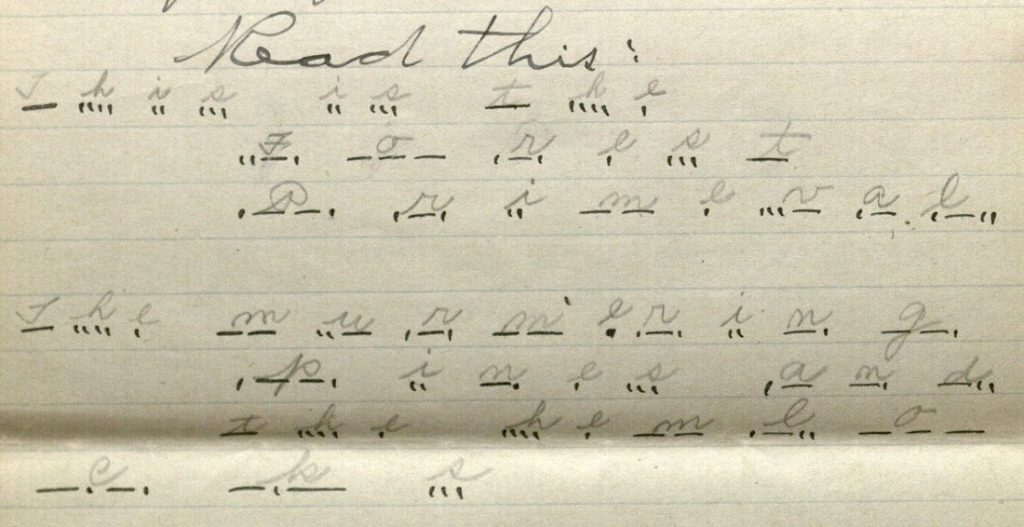

Do you understand this fully now? Read this:

Click image to enlarge.

T h i s i s t h e f o r e s t P r i m e v a l

_ …. .. … .. … _ …. . .._. _ _ _ ._. . … _ ._ _. ._. .. _ _ . …_ ._ ._..

T h e m u r m e r i n g p i n e s a n d t h e h e m l o

_ …. . _ _ .._ ._. _ _ . ._. .. _. _ _. ._ _. .. _. . … ._ _. _.. _ …. . …. . _ _ ._.. _ _ _ _

c k s

_._. _._ …

Write each letter above the signal as in the first word

T H I S

_ …. .. … (this) and send it back with your next letter, please.

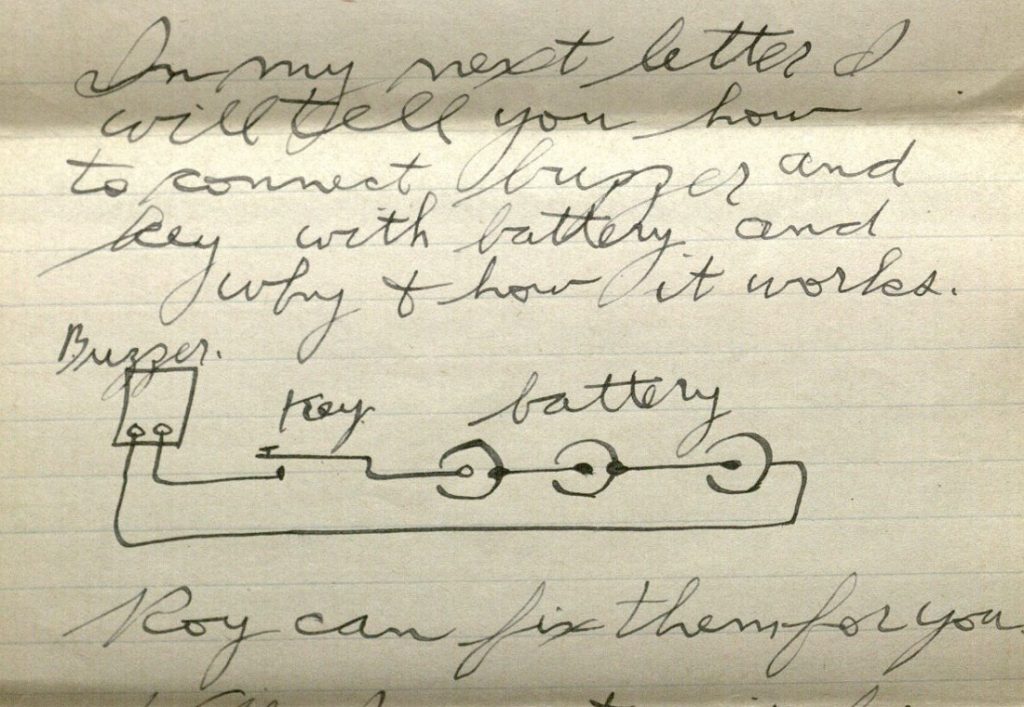

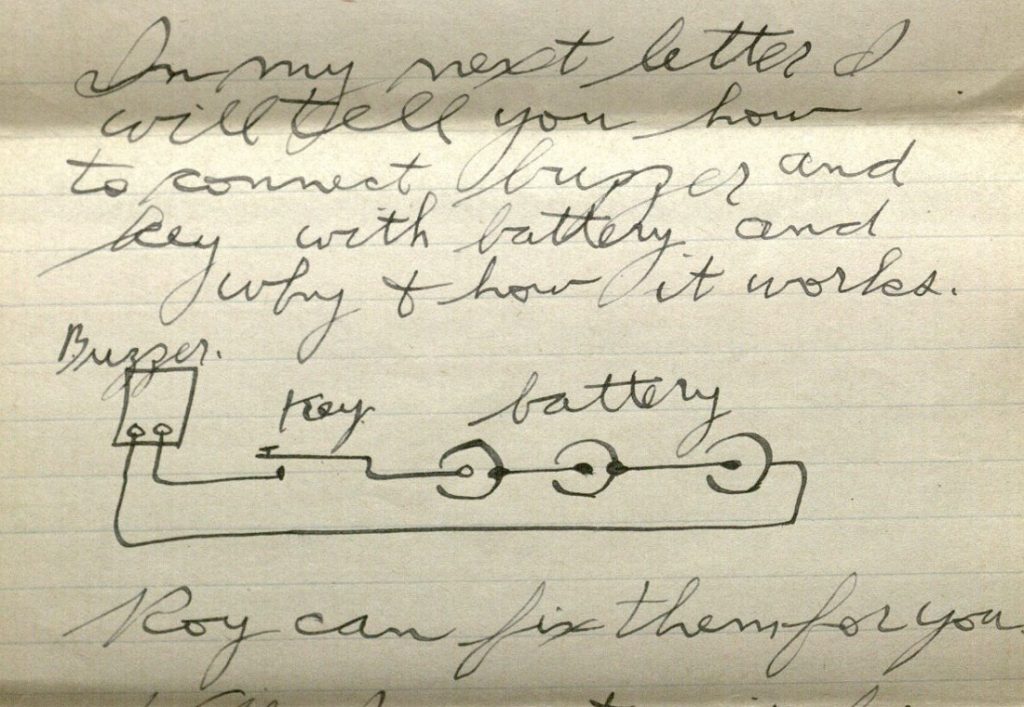

In my next letter I will tell you how to connect buzzer and key with battery and why and how it works.

Click image to enlarge.

Roy can fix them for you.

Well I must quit for this time.

Read paragraphs 845, 846, 847, 849, 850, 851, 852, 853 and 854, but remember that some of the letters in the Morse code are different than in the radio code, but that the method of handling the key is the same.

For instance a Morse J _._. is the same as a radio C _._. , and a Morse numeral 1 is the same as a radio P ._ _.

Well goodnight little girlie.

Forrest.

Tell Mother I got her letter O.K.

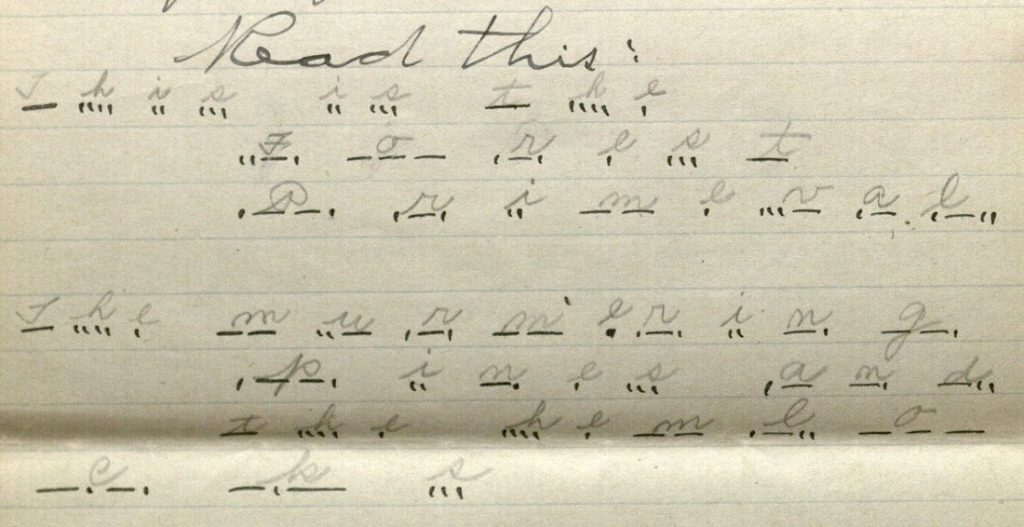

Click images to enlarge.

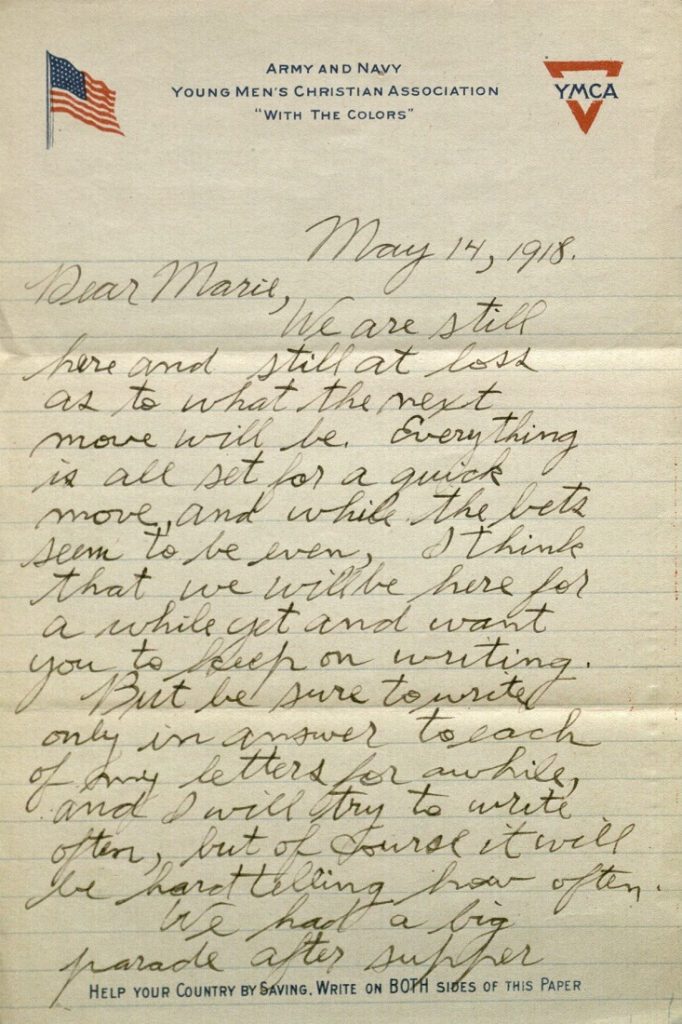

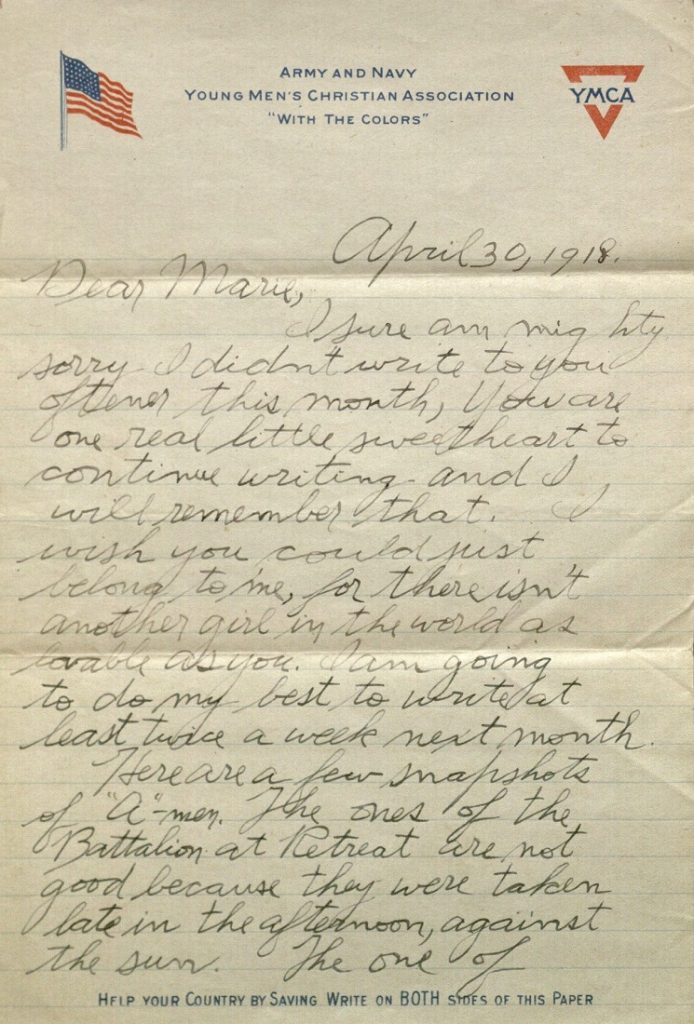

May 9, 1918.

Dear Marie,

Your letter of the 3rd just came today, so I guess it must have been lost some way.

I most certainly do think that you should get more sleep, as I said in answer to your letter of the 5th. I hope that you will be feeling better in a short time. Have you read “Starving America” through yet? What did you think of it and did you understand the main things pointed out by the author. I have read many books on food but believe that Alfred McCann has the only real common sense ideas on the subject. You will find his writings quite often in “Physical Culture” and his work is endorsed by McFadden in every detail.

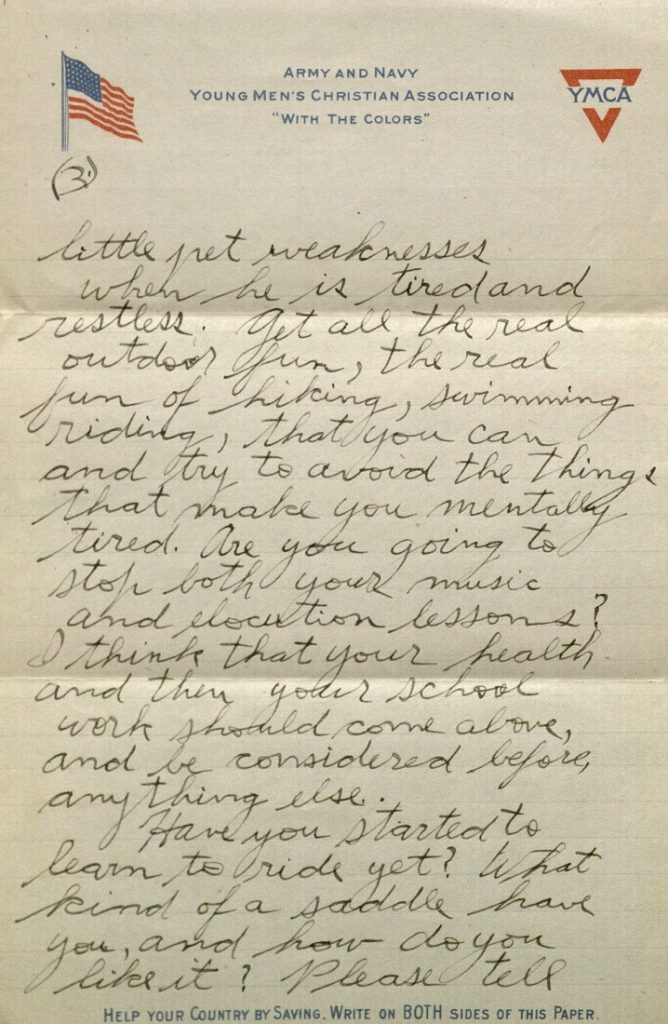

It would be fine if you could join an organization of real outdoor girls. Wouldn’t it be great if you could go to some kind of a girls camp for a short time during your school vacation. I had a fine time at the Phantom Lake Y.M.C.A. camp in 1914, and it seems as though there ought to be something similar for girls. Let’s talk more about this; you know I want you to have the best times possible and we may think of lots of things if we write about it.

Was glad to hear that Morse is coming here, for he will never find a better camp with a better bunch of fellows. Be sure to have him look me up.

Are you doing anything with the buzzer yet? Are you sure you are not getting interested in too many things?

I forgot to tell you about a few elementary things in forming letters.

The first thing to do is to practice making dot letters.

E I S H 5

. .. … …. …..

At first make the dots slowly with a full wrist (not finger movement) always uniformly and accurately.

When you make an i count 1, 2. That is dot, dot. And S would be 1, 2, 3; H would be 1, 2, 3, 4; just the same as counting time in music. The above is simple enough but some amateurs have trouble in combining dots and dashes without having too much space between the last dot and the first dash.

For instance the letter A = E+T or . _ , but there must be very little space between the dot and the dash — ._ and not . _ . The count is 1, 2 (the same as in I ..) and not 1, and 1.

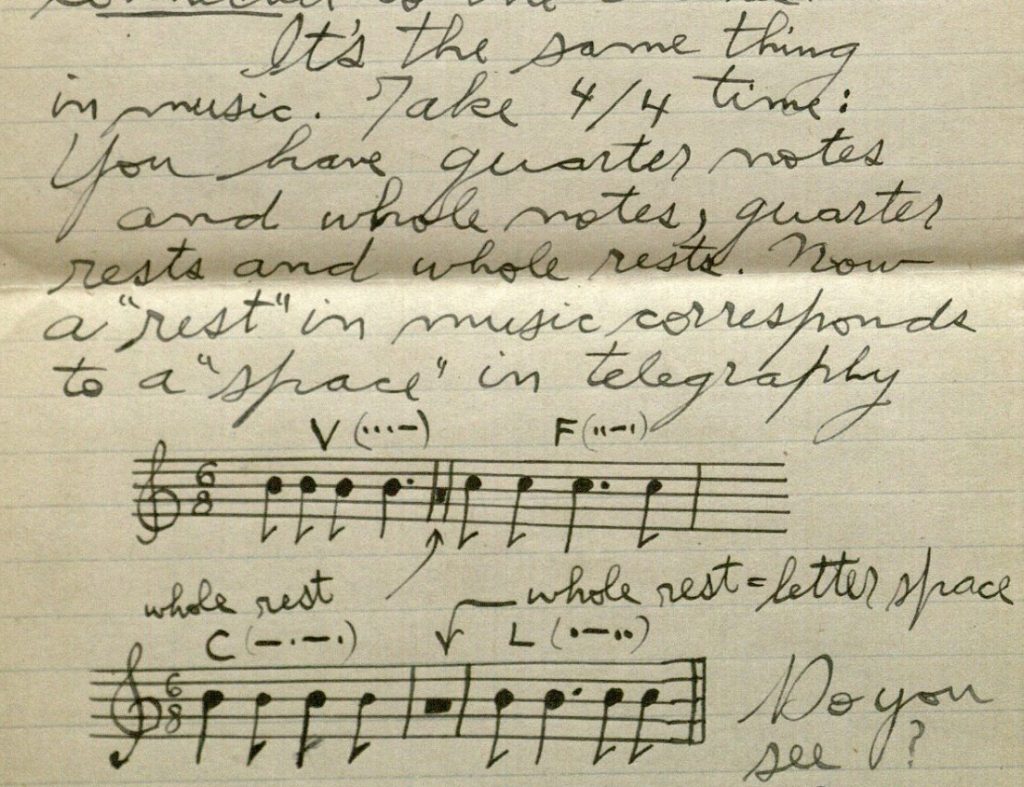

In making the letter “S,” which is three dots, the count is 1, 2, 3. Also, the letter U, which is two dots, dash, is counted 1, 2, 3 holding 3 so as to form a dash instead of a dot. Again, F is counted the same way; .._. is 1, 2, 3–, 1. V is …_ or 1, 2, 3, 4–. and not … _ [1 2 3, 1]. Do you see? The point is to have the dots connected to the dashes.

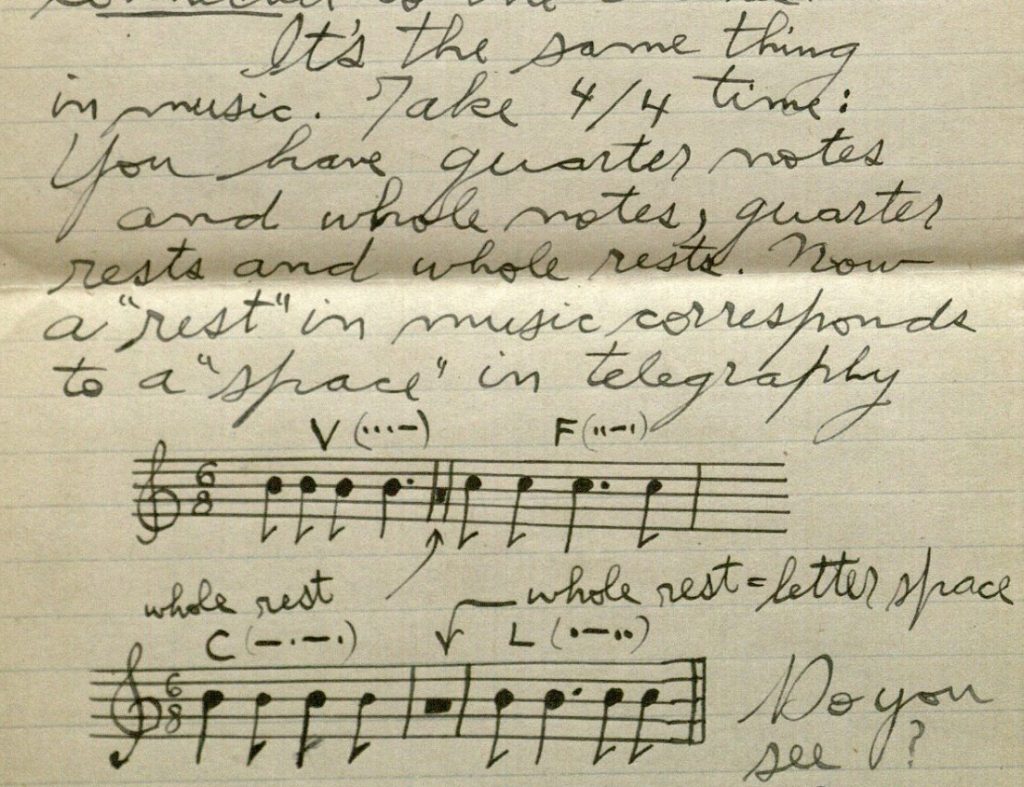

It’s the same thing in music. Take 4/4 time: You have quarter notes and whole notes, quarter rests and whole rests. Now a “rest” in music corresponds to a “space” in telegraphy

Click image to enlarge.

Do you see?

Now do you understand why to count 1 2 3 and 1 when you make F (.._.) instead of 1, 2, 1, 2.?

If you make F like this . . _ . it is going to sound like the word “in” which is .. _. [I N]. Also be careful not to make C (_._.) like double n (_. _.).

The best thing to do is the connect up that sending board of mine with the buzzer and battery and then if you use it right it will combine the dots and dashes with true mechanical precision and will accustom your ear to the proper sound of each letter. Tell me if you can find this board alright.

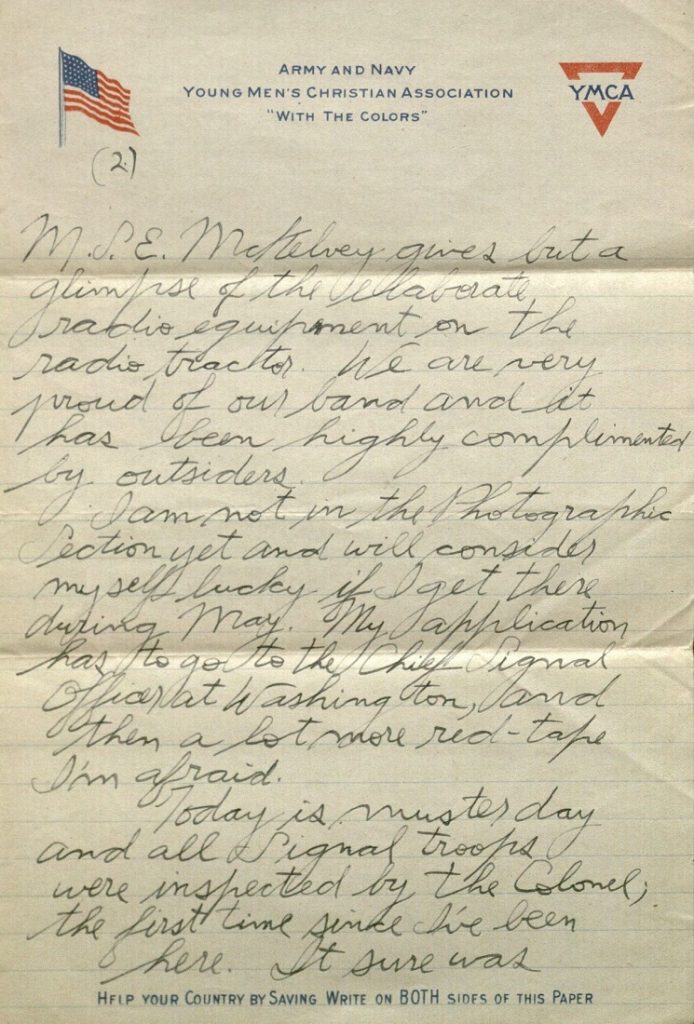

Today, Sergeant Baber gave the First Section a speed test in telegraphy and I have been rated at a speed of 20 words per minute, which is the average commercial radio operator’s speed.

Among my magazines you will find the July 1917 “Wireless Age.” Read the article on page 765, entitled “What Women Can Do, and Are Doing.” If you can’t find it I will send it to you.

With love,

Forrest.

May 11, 1918.

Dear Marie,

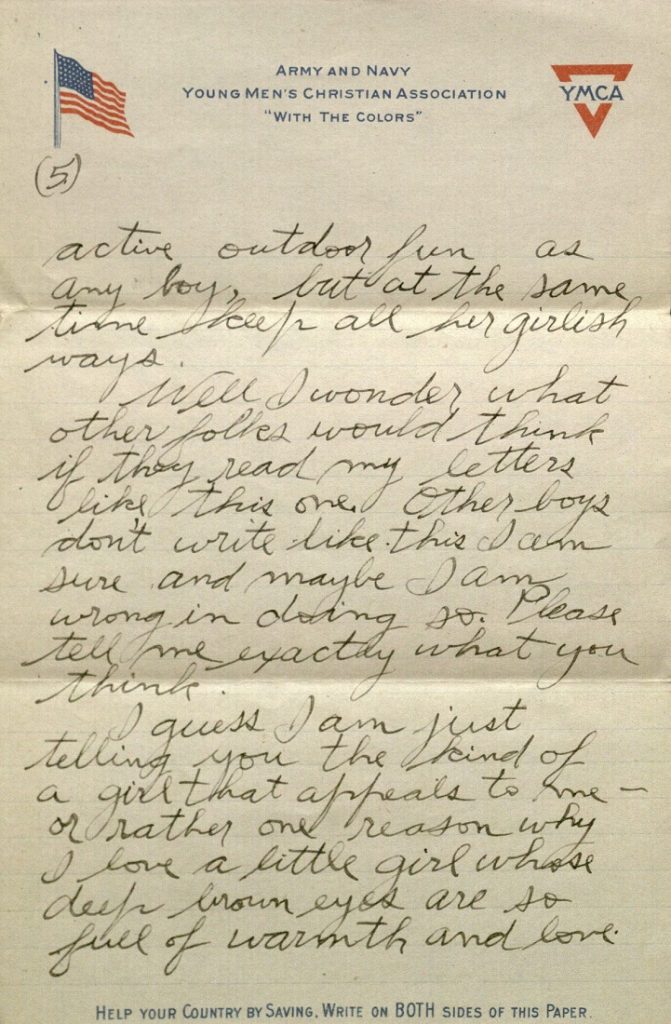

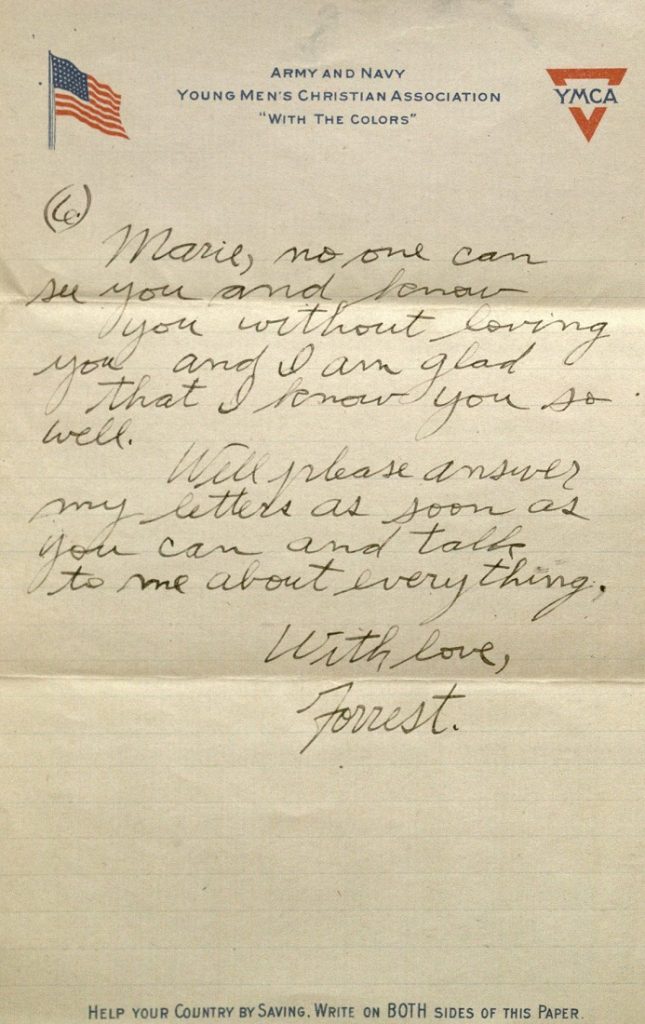

I think you got two letter this week didn’t you? Will be expecting a visit from Morse pretty soon now but can’t see how you expect me to like him if you like him nearly as well as you like me. And please be careful not to be too much in love with the Camp Grant boys because that sure would make me jealous.

I thought your reading, “The Service Flag” was good. Are you still taking both elocution and music? It seems to me you must be pretty busy, and I am not sure it would be a good thing for you to learn telegraphy.

What are your plans for this summer’s vacation, and what grade will you be in if you “pass” in June? Please really be my “little sister” and tell me more about yourself and what you intend to do.

Well I am going to go ahead and tell you more about telegraphy, but want you to tell me whether or not you really want to take the time and trouble to study it in earnest. If you you do want to learn it I will do a lot more to help you.

I explained in Mother’s letter, last night, how my transfer from Co A-6 has been blocked by Colonel Allison so you see I should become a pretty fair operator if I keep up with the progress I have already made. Of course it is slow work as telegraphy is only a small fraction of the “stuff” a signalman has to learn and we don’t get very much practice with it.

I am going to try to explain in as simple a manner as possible how the apparatus works. Now please be fair and tell me if you don’t really understand any of the things I try to explain because I am sure I can make everything quite plain and clear if you just tell me what you don’t “get.”

So hear goes with a few definitions, descriptions, etc. especially revised and calculated for a buzzer telegraph student.

— Will mail in a separate envelope – F.

Click image to enlarge.

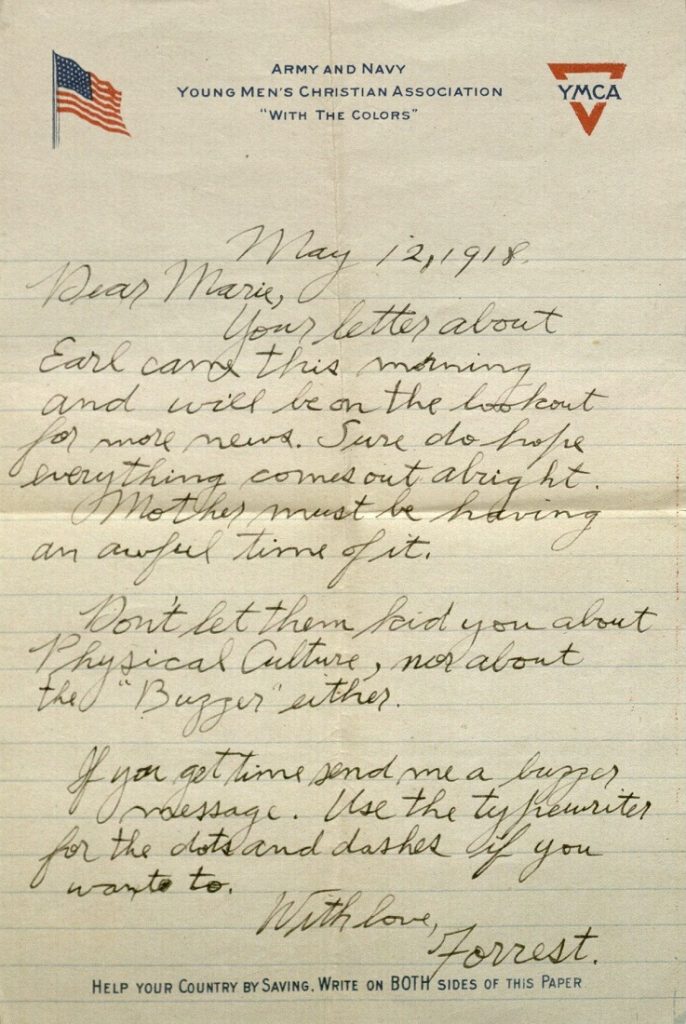

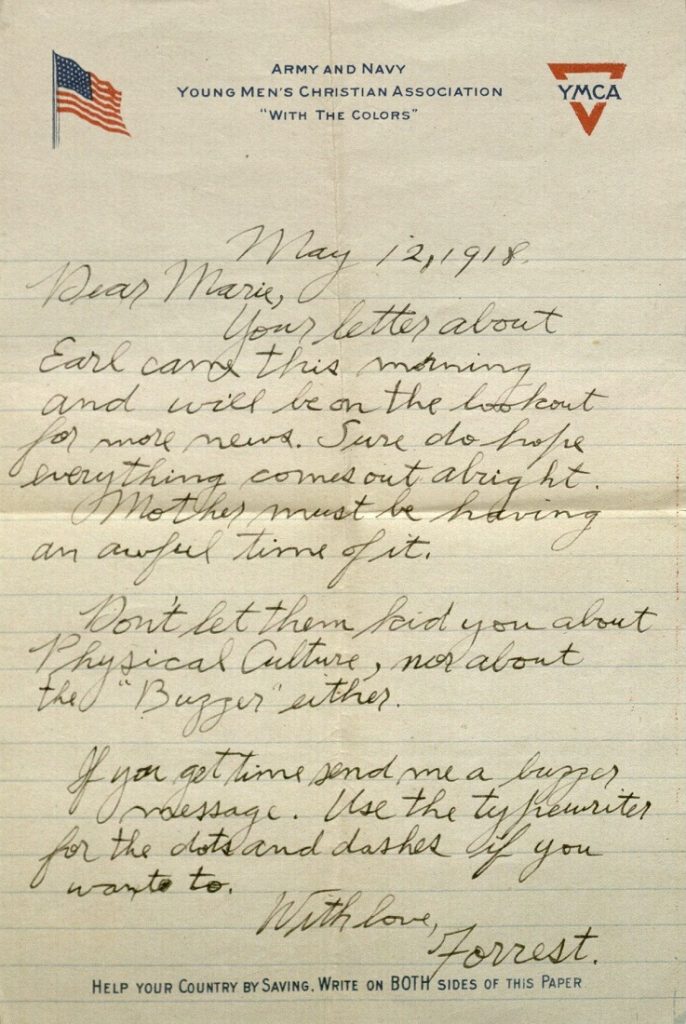

May 12, 1918.

Dear Marie,

Your letter about Earl [Forrest’s older half-brother Earl Treadway, born 1881]* came this morning and will be on the lookout for more news. Sure do hope everything comes out alright.

Mother must be having an awful time of it.

Don’t let them kid you about Physical Culture, nor about the “Buzzer” either.

If you get time send me a buzzer message. Use the typewriter for the dots and dashes if you want to.

With love,

Forrest.

*Earl Treadway had apparently died after Marie sent her letter to Forrest but before the date Forrest wrote this letter; Earl was buried on May 12, 1918. He was thirty-seven years old.

Click image to enlarge.

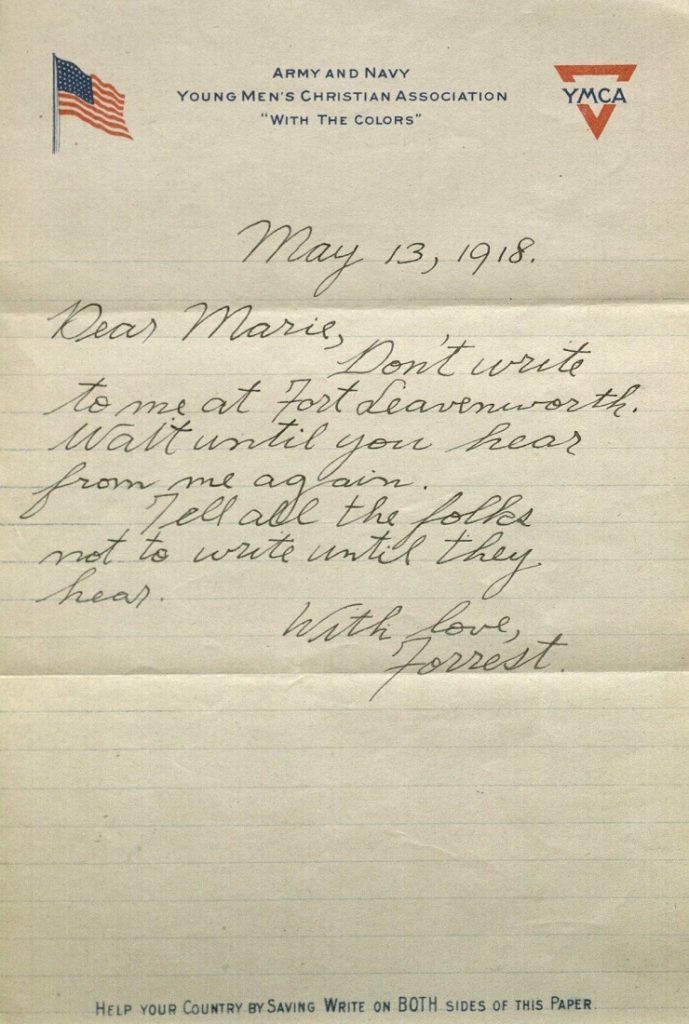

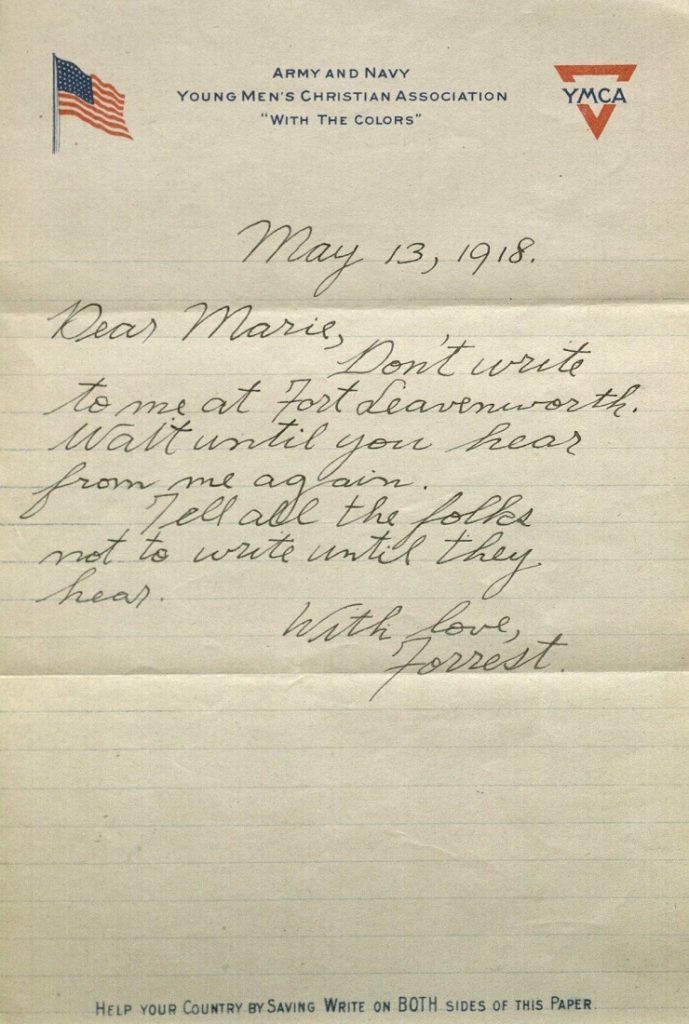

May 13, 1918.

Dear Marie,

Don’t write to me at Fort Leavenworth. Wait until you hear from me again.

Tell all the folks not to write until they hear.

With love,

Forrest.

Meredith Huff

Public Services

Emma Piazza

Public Services Student Assistant