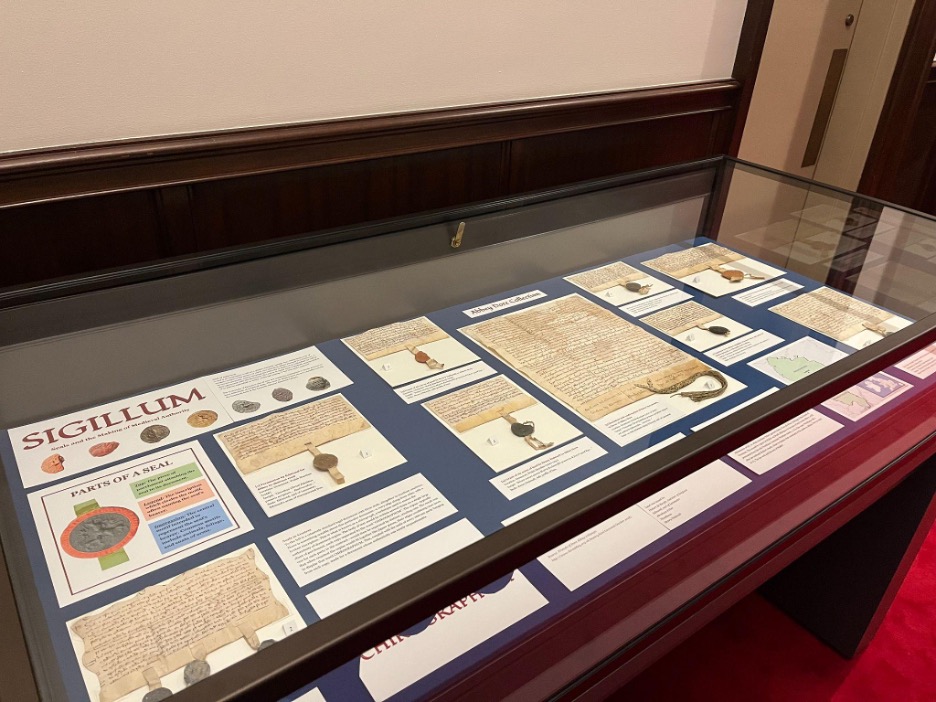

July Exhibit: Sigillum: Seals and the Making of Medieval Authority

July 17th, 2025Kenneth Spencer Research Library’s current short-term exhibit explores some choice items from the library’s collection of medieval seals. This is a collaborative project put together by myself – Kaya Taylor – and my collaborator Eli Kumin, both of us long-time student workers here at the library.

Eli and I have cultivated a particular interest in medieval wax seals, spurred on by our work on a Sanders Scholar research project under the supervision of Dr. John McEwan. Beginning in September 2024, we spent the project exploring the Abbey Dore collection (Call Number: MS Q80) at Spencer, given the remarkably well-preserved seals and documents dating back from the 12th and 13th centuries. As the project came to a close in May 2025, Eli and I realized that we could memorialize our work and interests in the form of an exhibit case. Titled Sigillum, it is our way of giving others a look into these fascinating and unique pieces of history, here to be enjoyed roughly 4,000 miles away from where they originated.

The overarching narrative of the Abbey Dore collection is one of property and the interplay between royal and religious power in the medieval period. The language used in the documents points to the exchange of land for the salvation of the donors and their loved ones, e.g. “for her soul and the soul of Madoc [her husband]” (Call Number: MS Q80:13).

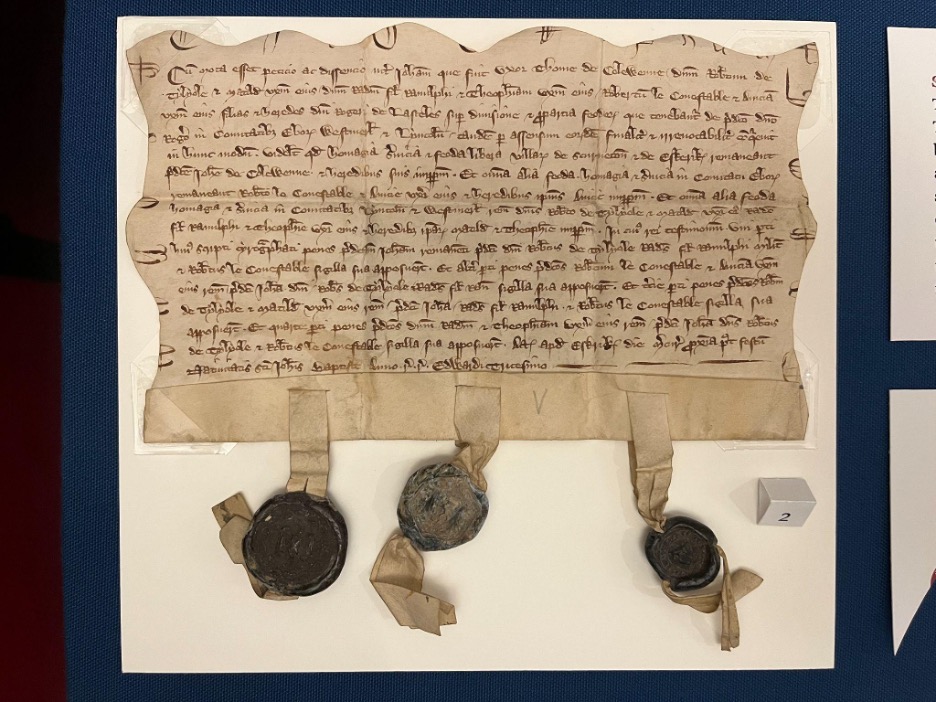

Visitors may notice there is one document unlike the others in the exhibit case, labeled “land conveyance of Sir Roger Lasceles to his four daughters” (Call Number: MS C150). Although separate from the Abbey Dore collection, this document is included because it’s a particular favorite of ours and it boasts several unique qualities: a chirograph edge and three intact seals with very clear impressions. We chose to include it at the starting point of the exhibit because of its eye-catching quality, pulling visitors into the discussion of further seals and documents within the case.

Although Eli and I came to know the Abbey Dore collection very well over time, we still felt a bit confused as to the relative geography of the Welsh Marches and the locations mentioned in the collection. We felt that visitors could benefit from seeing a map of the region, and so we resolved to make one that centered the relevant places and landmarks stretching across the Welsh-English border. Ultimately, we used ArcGIS software to put together the map seen in the exhibit.

We hope that Sigillum gives visitors a chance to appreciate not just the wax seals themselves, but the real human stories that stand behind them. We are excited to offer this glimpse into the medieval past, and grateful for the opportunity to bring these objects to light at Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

Sigillum: Seals and the Making of Medieval Authority is free and open to the public in Spencer’s North Gallery through July 31st.

Kaya Taylor and Eli Kumin

Public Services student assistants

KU Libraries Sanders Scholars 2024-2025