That’s Distinctive!: Winnie-the-Pooh Cookbook

September 8th, 2023Check the blog each Friday for a new “That’s Distinctive!” post. I created the series because I genuinely believe there is something in our collections for everyone, whether you’re writing a paper or just want to have a look. “That’s Distinctive!” will provide a more lighthearted glimpse into the diverse and unique materials at Spencer – including items that many people may not realize the library holds. If you have suggested topics for a future item feature or questions about the collections, feel free to leave a comment at the bottom of this page.

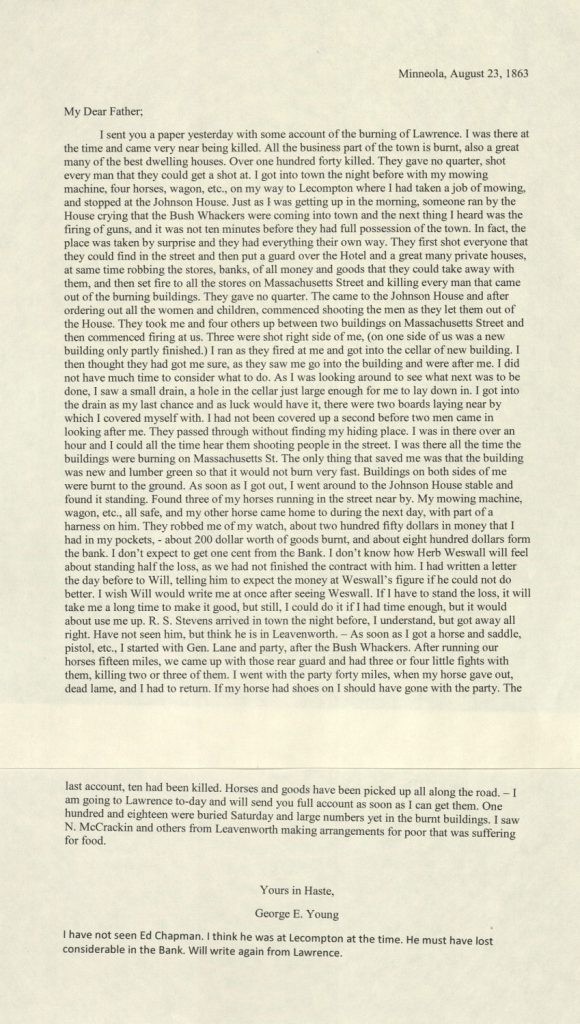

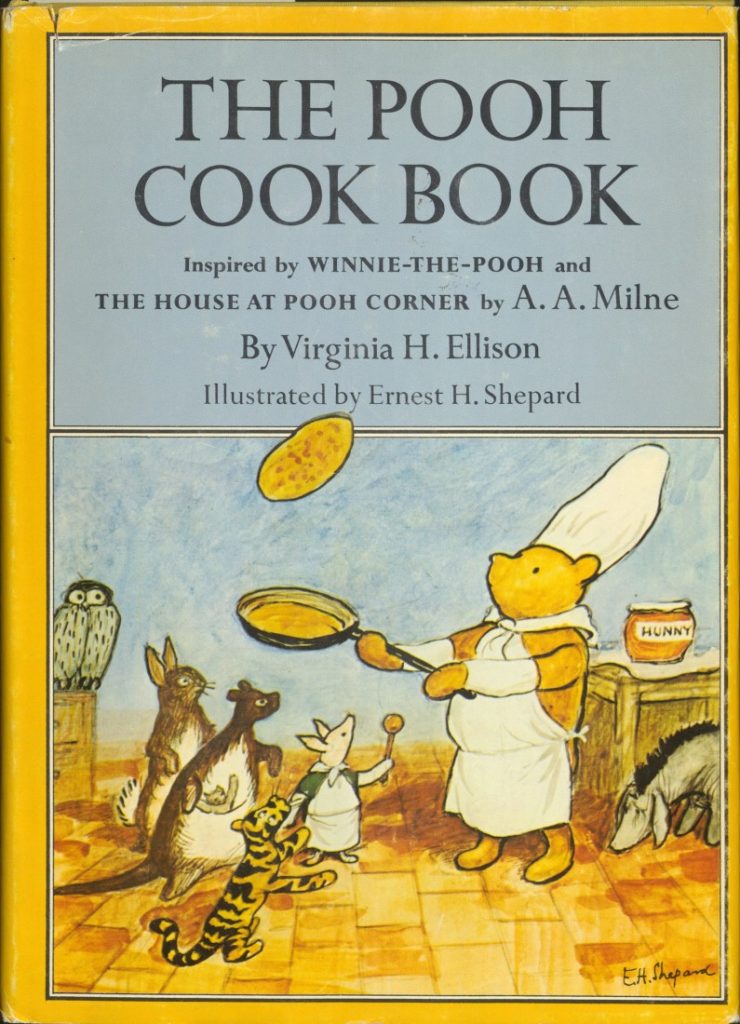

This week on That’s Distinctive! we share The Pooh Cook Book from Special Collections. Released in 1969, The Pooh Cook Book was written by Virginia H. Ellison after she became inspired by Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at Pooh Corner by A. A. Milne. Offering a variety of recipes, most of which include honey, the book offers a fun interactive activity surrounding Winnie-the-Pooh. After being updated and redesigned, the book was re-released in 2010 as The Winnie-the-Pooh Cookbook.

According to Wikipedia, Winnie-the-Pooh “first appeared by name on 24 December 1925, in a Christmas story commissioned and published by the London newspaper Evening News.” In October of 1926, the first collection of Pooh stories appeared in A. A. Milne’s book titled Winnie-the-Pooh. The book was an immediate success and was followed by The House at Pooh Corner in 1928. Since 1966, Pooh and his friends have appeared in many animated films and a television series produced by Walt Disney Productions along with other adaptations throughout the years. Pooh and his friends have been loved by millions from the moment of their creation, and they continue to be enjoyed today.

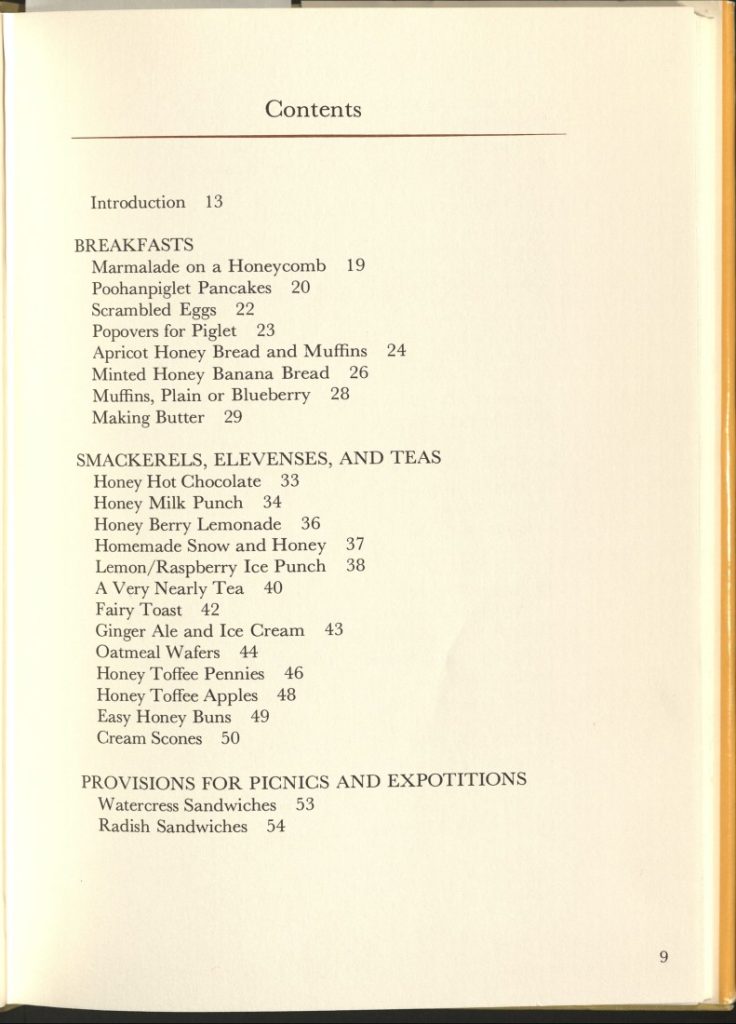

A description of the updated The Winnie-the-Pooh Cookbook states that “the famously rotund bear is happiest when in possession of a brimming pot of honey, but when it comes time for meals and smackerels, the residents of the Hundred Acre Wood need something a little more substantial. This delightful collection contains over fifty tried-and-true recipes for readers of all ages to make and enjoy, starting with Poohanpiglet pancakes and ending with a recipe for getting thin-with honey sauces, holiday treats, and dishes for every mealtime in between.”

The copy of The Pooh Cook Book in Spencer’s collections was a gift of Elizabeth M. Snyder. If her name sounds familiar, it’s because she is the founder of KU Libraries’ long-running Snyder Book Collecting Contest.

Why this book? Well, first, why not? And second, who doesn’t love Winnie-the-Pooh? The cookbook offers a great opportunity to combine (or create) childhood memories with quality time. As author Virginia H. Ellison writes, “The Pooh Cook Book is particularly useful for special occasions, real or invented, and meant to make what might be an ordinary day into a festive one – almost as good as a birthday or a holiday” (14). This volume also shows that the library houses materials for people of all ages. Additionally, the library doesn’t just offer informational materials; it also offers things that are just fun to look at.

Tiffany McIntosh

Public Services