Books Will Speak Plain: Creating a Design Binding

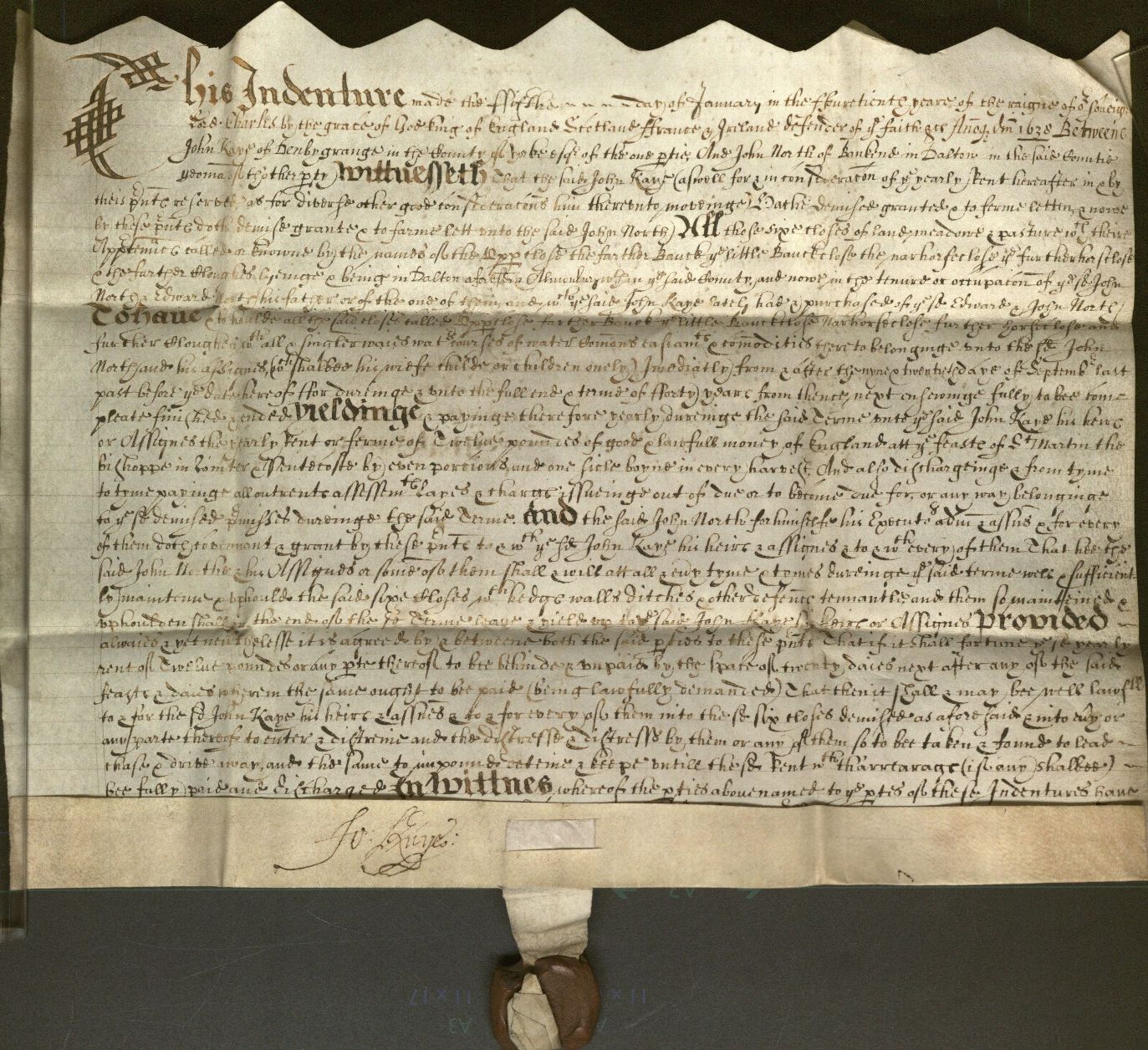

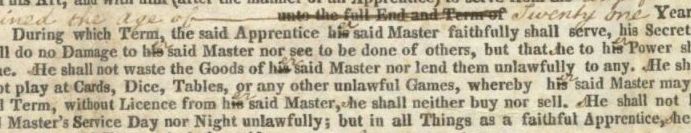

November 15th, 2013The Guild of Book Workers (GBW) is a national organization whose members are bookbinders, book artists, book conservators, calligraphers, and other book enthusiasts. The Midwest Chapter of GBW recently hosted a jurying of design bindings for a traveling exhibition, which opened at Spencer Library on Monday, November 11. Entrants were required to bind a copy of Julia Miller’s Books Will Speak Plain: A Handbook for Identifying and Describing Historical Bindings (Legacy Press, 2010).

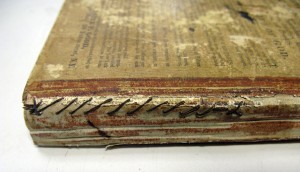

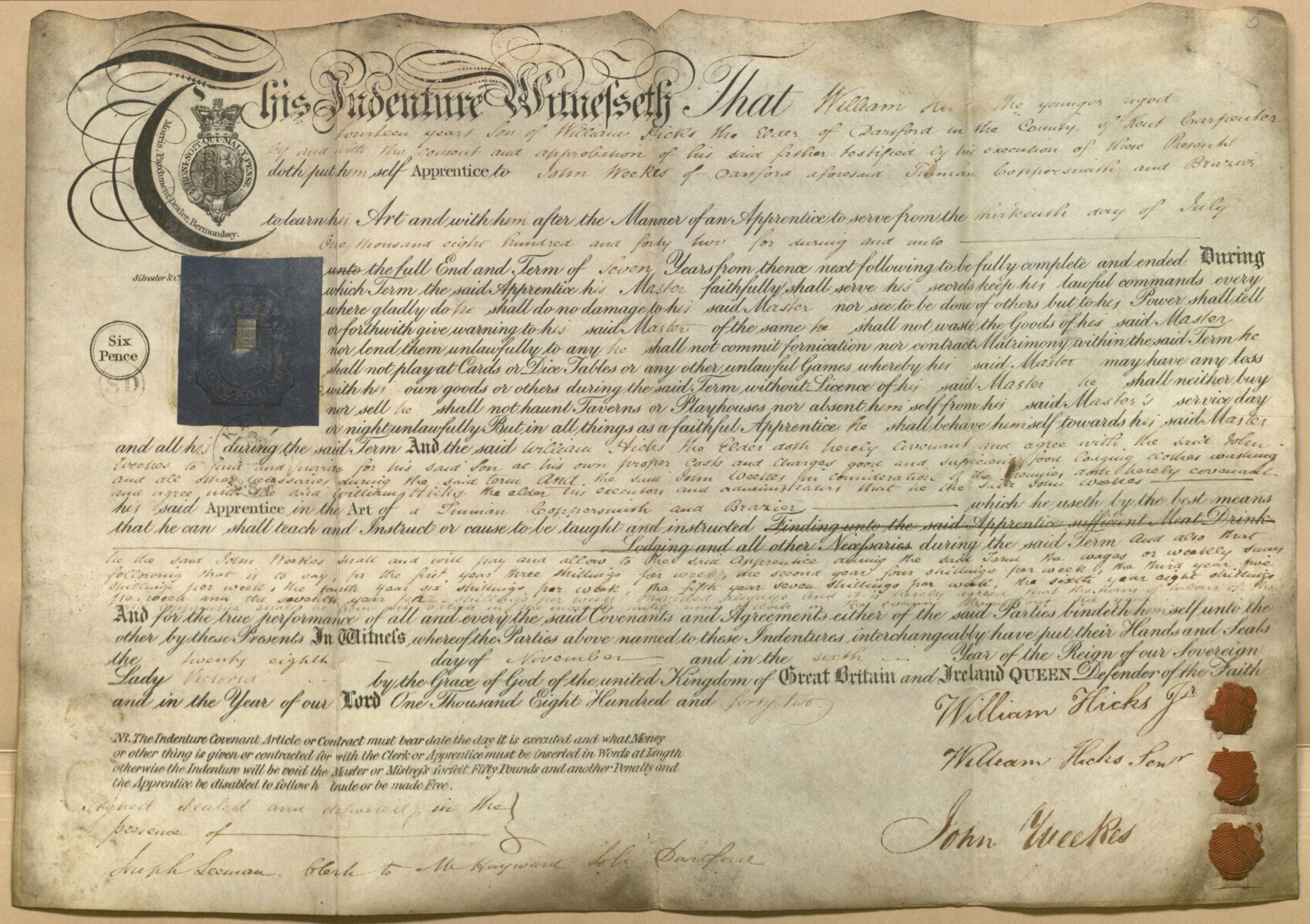

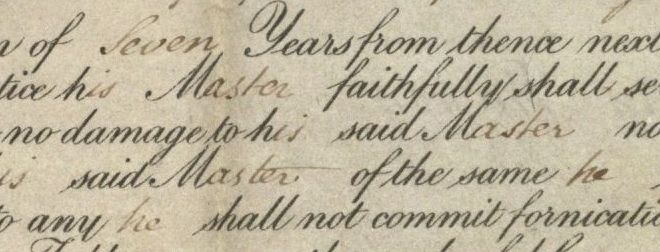

What follows is a description of how I bound my copy of Books Will Speak Plain. I gained inspiration for my binding by examining historic bookbindings from Special Collections at Spencer Library. Because Miller’s book covers the history of bookbinding, it seemed logical to create a book that touched on book history in some fashion. In my role as conservator, I am fortunate to have the chance to closely examine books and have long been interested in evidence of past repair. I found various examples in Spencer’s stacks of books that had been repaired by sewing on loose parts, such as a detaching spine or cover board. I decided to use this concept as the driving force in the design of my book.

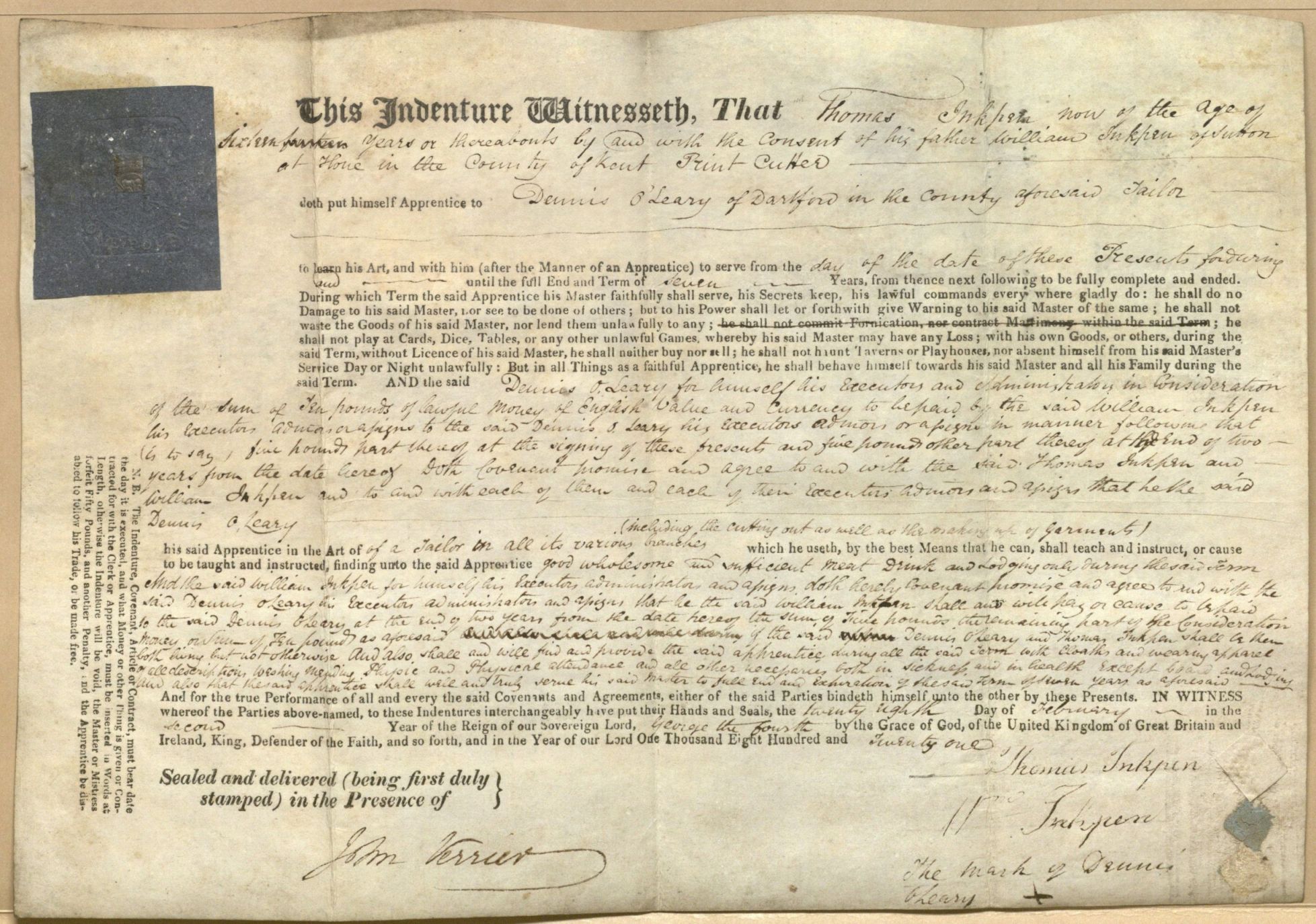

Detail of sewing repair on Sunderland, La Roy. Pathetism; with practical instructions. New York, 1843. Call number B6443. Click image to enlarge.

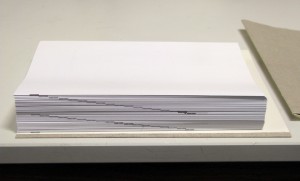

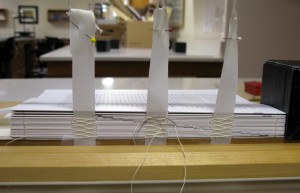

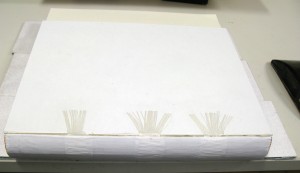

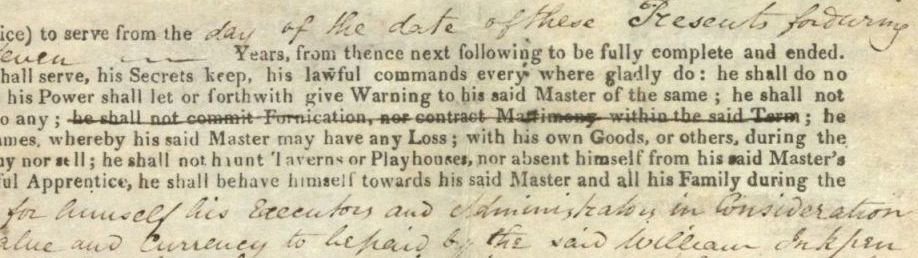

The 500-page book arrived in folded sheets of paper. The textblock paper was dense, which ruled out certain styles of bookbinding that could not support the weight of such heavy paper. The book was sewn on three sewing supports made out of the fiber ramie. The book was sewn on a sewing frame, using a link stitch.

Left: Book in sheets. Right: Sewing book on a sewing frame. Click images to enlarge.

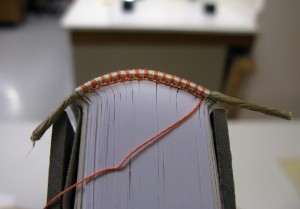

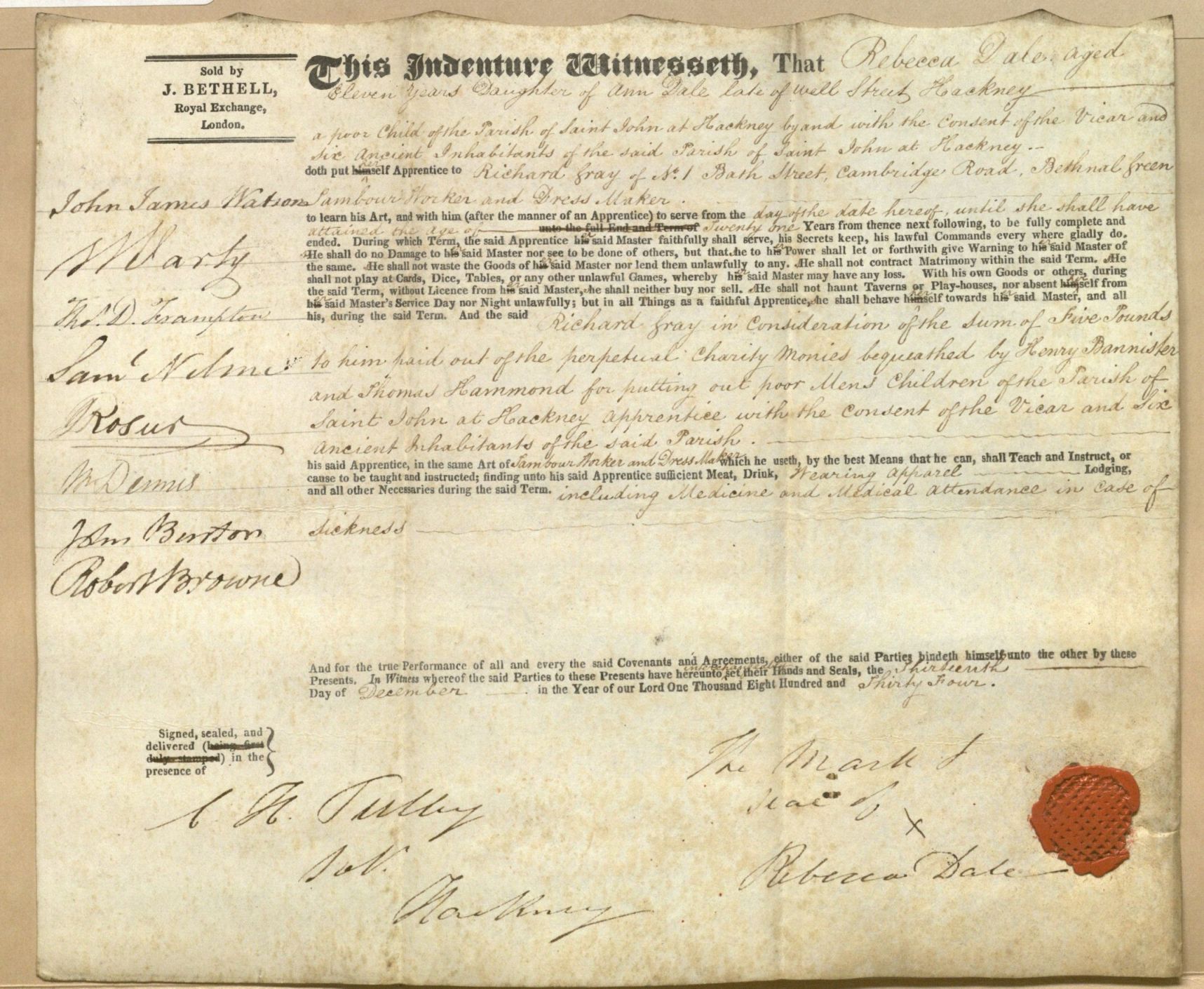

I sewed silk endbands in cream and orange. The silk bands were sewn around a core of linen thread. Next the book’s spine was lined to provide some rigidity and set the round spine shape. I first applied a layer of Japanese paper with wheat starch paste, then a layer of Western paper, and finally airplane linen.

Left: Sewing endbands with orange and cream thread. Right: Spine linings of paper and airplane linen. Click images to enlarge.

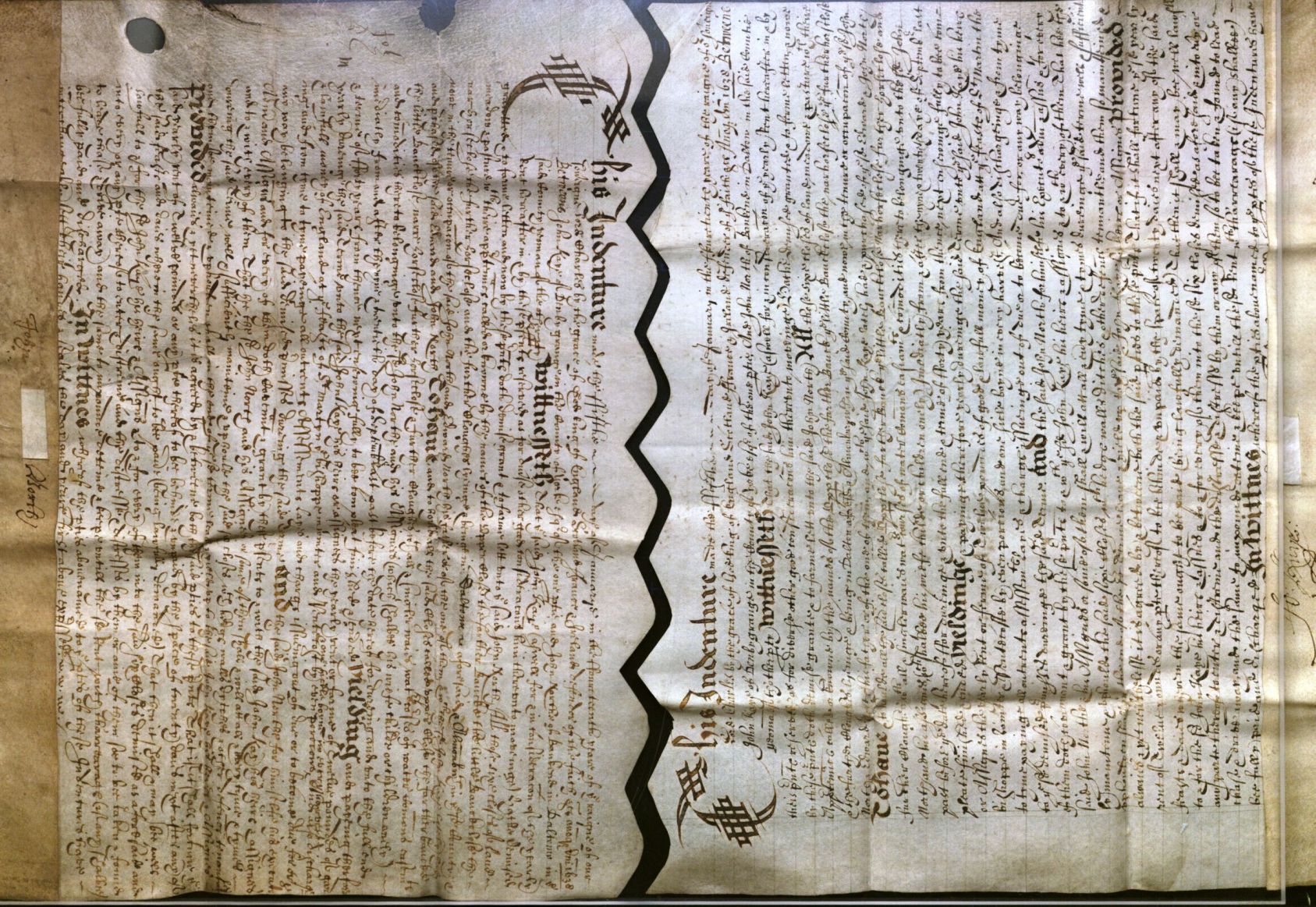

Next the ramie bands, around which book was sewn, were frayed out and adhered to the book boards.

Boards attached to textblock via frayed-out ramieband sewing supports. Click image to enlarge.

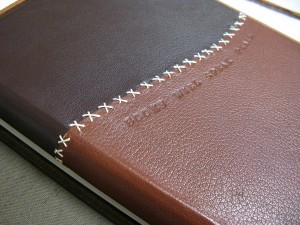

Once the boards were on, it was time to cover the book. I decided to use two contrasting colors of morocco (goatskin) leather, sewed together with coarse thread.

First I cut out templates for the leather pieces. The edges of the leather were pared to a thin edge, especially where the two pieces overlapped in the middle of the book.

Left: Cut leather pieces with templates. Right: Joined leather pieces wrapped around textblock. Click images to enlarge.

The leather was attached with wheat starch paste. Here you see the headcap tied up with thread in a finishing press to help give the leather a good shape where the boards and spine meet.

Book covered with leather, with headcap tied up with thread. Click image to enlarge.

Once the leather was applied to the book, next came labeling. I used individual brass letter tools, heated on a hotplate. (A stove designed for the purpose is preferable, but I didn’t have one at my disposal.) Each letter is “branded” individually in the leather. When it is left like that, with no gold leaf or foil applied over it, it is called “blind” tooling.

Left: Tools resting on hot plate. Right: Detail of finished book with blind tooling. Click images to enlarge.

This book was accepted into the blind juried show. You can see it and other fine bindings in the Plainly Spoken exhibit at Spencer Library through January 6, 2014. If you are near Lawrence, please come to the Gallery Talk on November 21, from 3-4 PM. The Spencer exhibit features both the design bindings as well as historical examples from Special Collection that complement them.

Whitney Baker

Head, Conservation Services