Making the Hand-Colored Lithographic Prints in John Gould’s Bird Books

September 8th, 2020We are periodically sharing some of the materials that are featured in Spencer Research Library’s North Gallery permanent exhibit. We hope you’ll be able to visit the library and explore the full exhibit in person! This week’s post highlights materials by and information about English ornithologist John Gould.

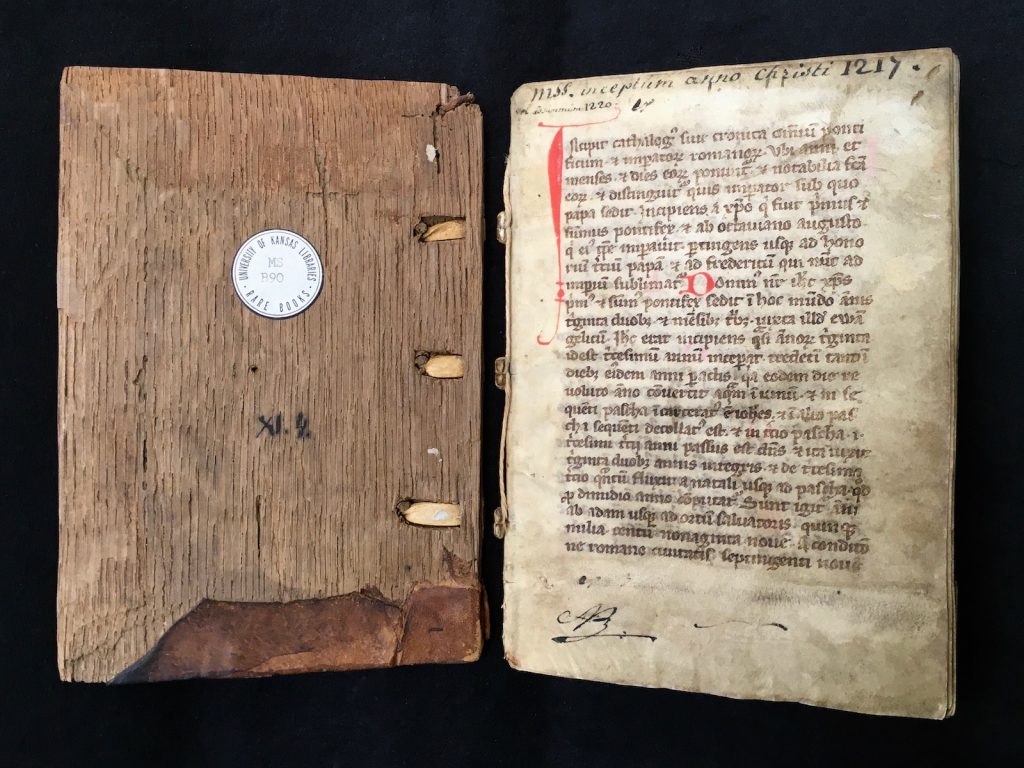

John Gould, an English ornithologist based in London, published large, lavishly illustrated books about birds of the world from 1830 until his death in 1881. Kenneth Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas holds 47 large-format volumes published by Gould, as well as nearly 2000 preliminary drawings, watercolors, tracings, lithographic stones, and proof prints from his artistic workshop. Digitized a decade ago, our Gould collection has recently migrated to new Islandora software that makes searching for bird images within the volumes as easy as finding the separate pieces of preliminary art. The digitized Gould collection is accessible at the University of Kansas Libraries website.

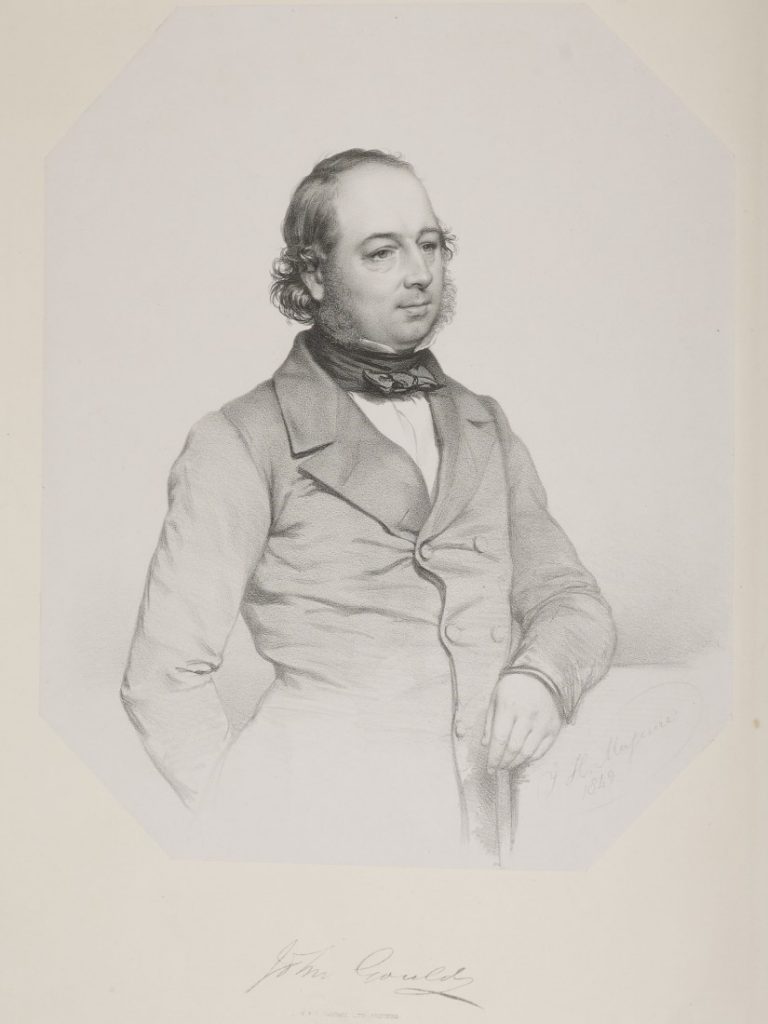

The son of a humble gardener, John Gould had spent his boyhood in rural England. His youthful interest in birds and taxidermy would later grow into a career as a publisher of bird books. Hired in 1827 by the recently founded Zoological Society of London, his work maintaining their collection of bird skins enabled him to learn from member ornithologists. Gould and his wife Elizabeth, an amateur artist, ventured into ornithological publishing in 1830 with a book about birds of the Himalaya Mountains.

High-quality digital images downloaded from University of Kansas Libraries website are included here to help explain how the beautiful lithographic prints of birds that illustrate Gould’s books were made. Lithography was a chemical printing process based on the antipathy between grease and water. It involved drawing with greasy ink or crayon on blocks of fine-grained limestone imported from Germany. Invented in Bavaria about 1798 by Aloys Senefelder, lithography soon spread throughout Europe and beyond. By the mid 1800s lithography had replaced copper engraving as the preferred method for quality book illustration, because it was easier and faster (and therefore cheaper) to execute.

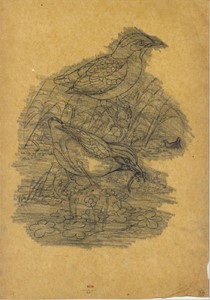

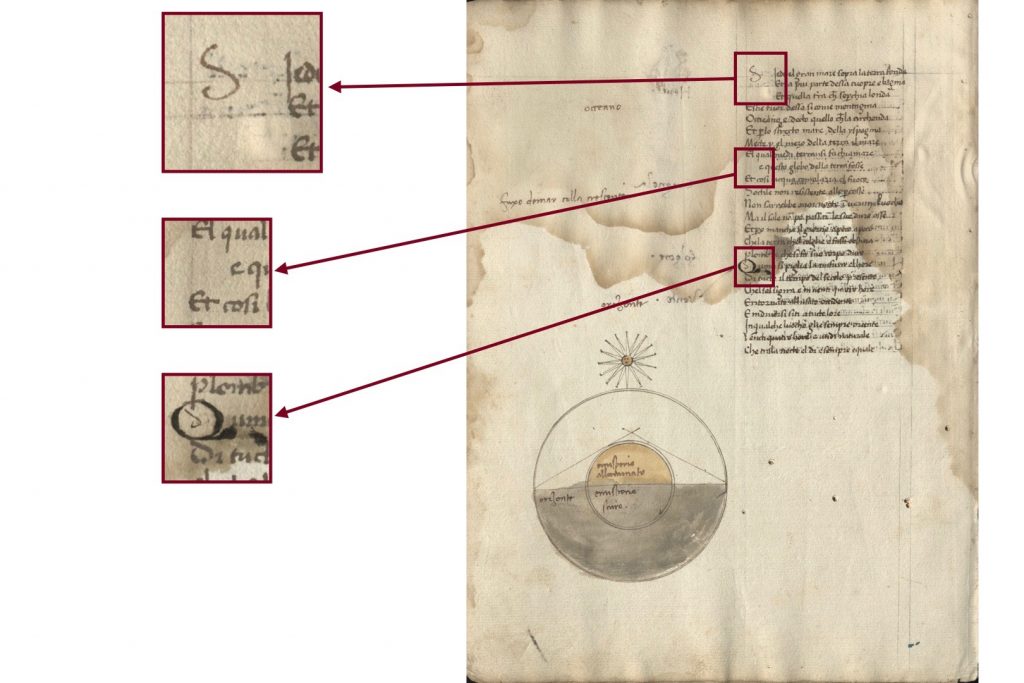

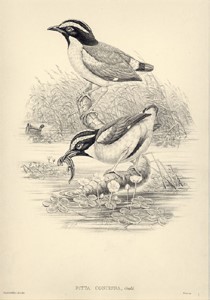

An initial rough sketch on paper, often drawn by John Gould himself, began the bird illustration process. The multiple lines and erasures on this sketch of two Asian ground thrushes (Pitta concinna) reflect Gould’s search for the best composition.

One of Gould’s artists, in this case William Hart, then developed the sketch into a detailed watercolor painting to be approved by Gould, who insisted on accurate proportions and coloring.

Next Hart copied the outlines onto tracing paper and blackened the reverse side with soft lead pencil. By laying the tracing paper on a block of limestone prepared for lithographic printing and re-tracing the outlines, he was able to transfer a non-printing guide image onto the printing surface.

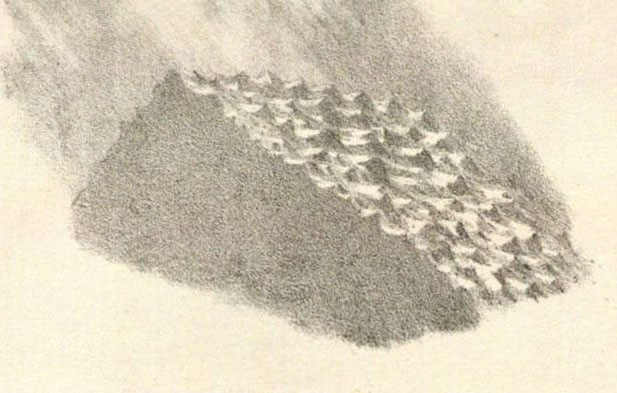

Following the guide lines, Hart has used a greasy lithographic crayon to draw and shade the bird image on the lithographic stone. The stone had been rubbed with fine sand and water to give it a velvety texture or grain to which the crayon would adhere.

Close examination with a magnifier would show small irregular dots of crayon adhering to the grained surface of the stone. At normal reading distance, though, the viewer’s eye blends the tiny dots and perceives them as shades of gray.

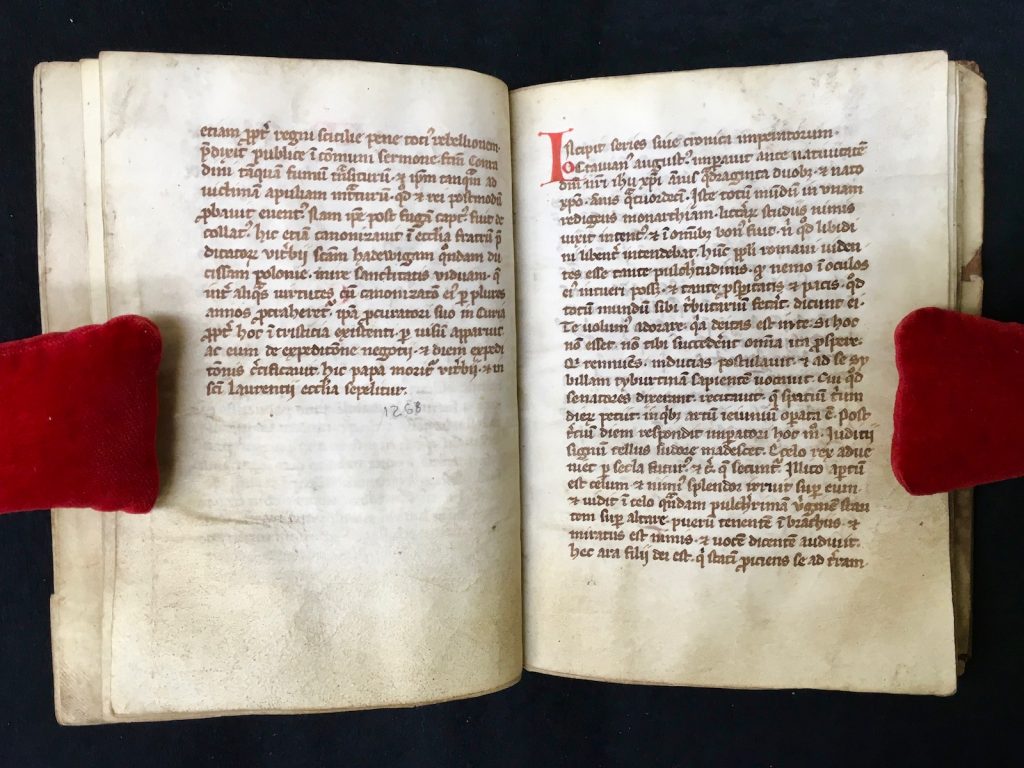

Turning the drawing on stone into a printing image was a chemical process. First, the crayon drawing was lightly etched with a gum arabic solution, which adhered to the non-image areas and made the bare stone surface there more water receptive. The crayon image was then washed out with turpentine, which formed a thin coating on the image making it receptive to the greasy printing ink.

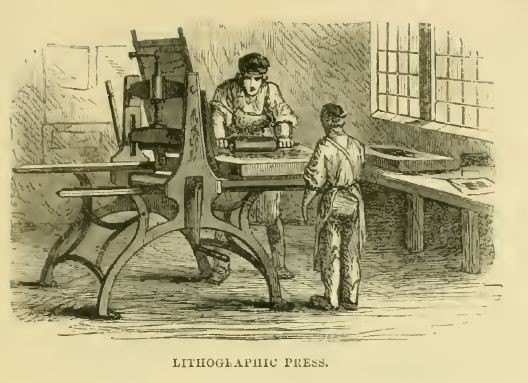

Next the printer placed the stone on the bed of a lithographic printing press. Before inking, the stone was wetted, so the greasy black ink would adhere only to the crayon image. A blank sheet of paper was then placed on the inked stone and pressed against it by a scraper bar to transfer the black ink onto the paper, forming the printed image.

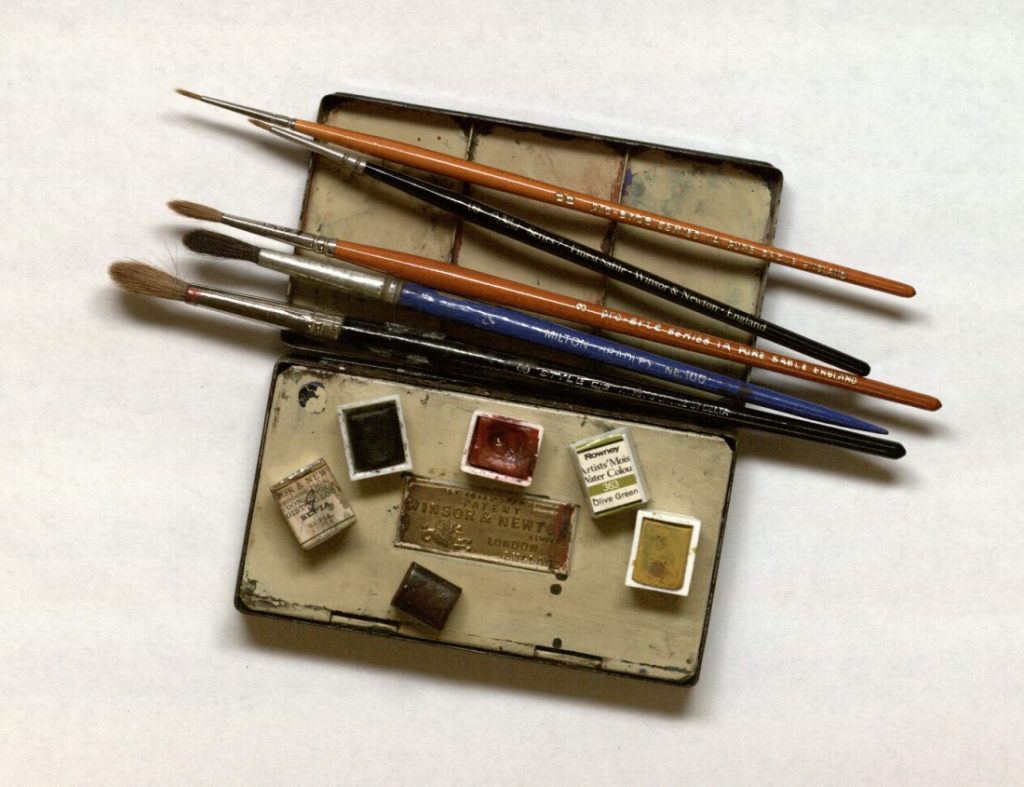

After the ink had dried, the print was hand colored with watercolors, copying a colored master print (called a pattern plate) that had been approved by Gould. Gould’s colorer was Henry Bayfield, who employed the female members of his family to help with adding watercolor washes by hand to uncolored prints. The washes not only tinted the black print but also blended visually with the lithographic shading to convey the shape, color and texture of the feathered bodies of the birds.

Call Number: Gould Drawing 1134. Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

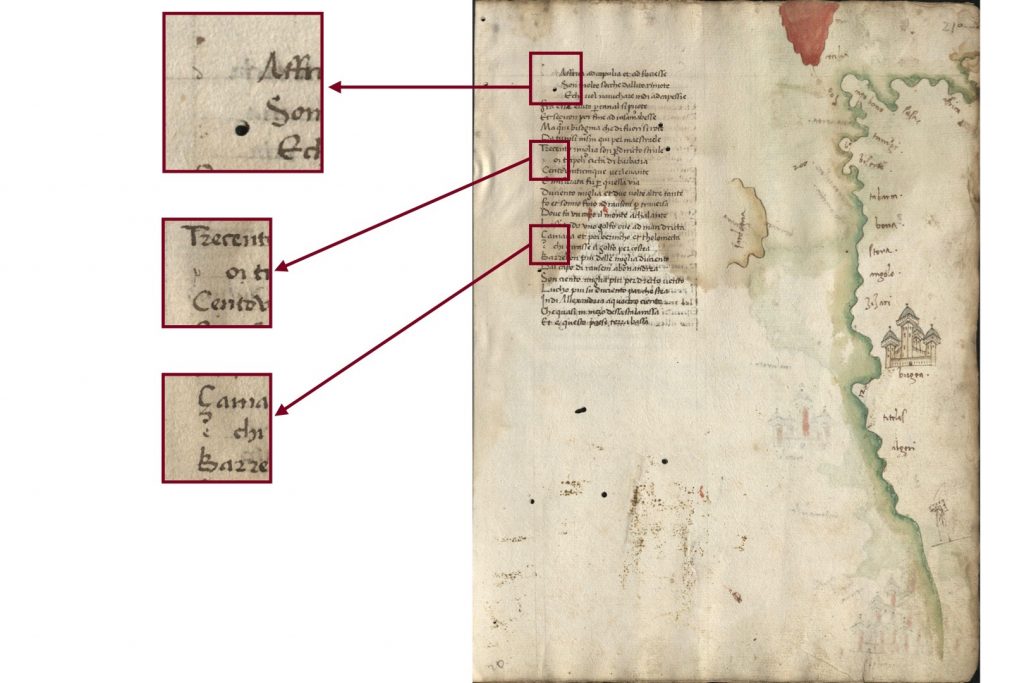

Above, in the middle, the print of a pair of ground thrushes (Pitta concinna) illustrates Gould’s book about the Birds of New Guinea. On the facing page is Gould’s scientific description of the bird, set in metal type and printed by the relief letterpress process. After being printed separately, the parts of the book were issued in installments to subscribers, who had them bound as volumes once complete.

In vogue during the middle decades of the 19th century, such hand-colored lithographic prints of birds were superior in quality to the earlier hand-colored copper-engraved prints they had replaced. Although succeeded in the second half of the 19th century by color-printed chromolithographs, in the early 20th century by four-color process halftone photolithographs, and in the late 20th century by digital images, Gould’s hand-colored lithographic prints are still esteemed as quality bird images.

However, the Gould example is only one of the stories that could be told about lithography’s impact on the production of graphic images during the 19th century. This is because lithography’s versatility as a chemical process meant that it was not just one new technology but rather a cluster of image making technologies that could be used separately or combined in innovative ways. As well as drawing on grained stone with a crayon, early practitioners drew on polished stone with pen and ink, “engraved” (more accurately “scribed”) lines in a thin coating of gum arabic, or drew with lithographic ink on coated transfer paper. After the mid-19th century these were combined with new methods of transferring images to the printing surface and of printing in color (chromolithography) from multiple lithographic stones or (later) from metal plates. A ground-breaking example of chromolithography is Owen Jones’ book, Plans, elevations, sections, and details of the Alhambra (London, 1842-1845. Drawing flat areas of color on lithographic stones, one stone per color, he printed multi-colored illustrations in remarkably exact registration for his book, but this is a single example. The story of all the many technologies associated with chromolithography would fill a book, one which, in fact, has been well told by Michael Twyman in his 728-page book, A History of Chromolithography: Printed Colour for All (London: The British Library and New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2013).

Karen Severud Cook

Special Collections Librarian