Students’ Adventures in University Archives

June 25th, 2019This week’s post was written by Hannah Scupham, an English 102 instructor and Doctoral Candidate in English Literature at the University of Kansas.

“I feel like a detective!”

“I didn’t even know this stuff was here!”

“This is SO cool!”

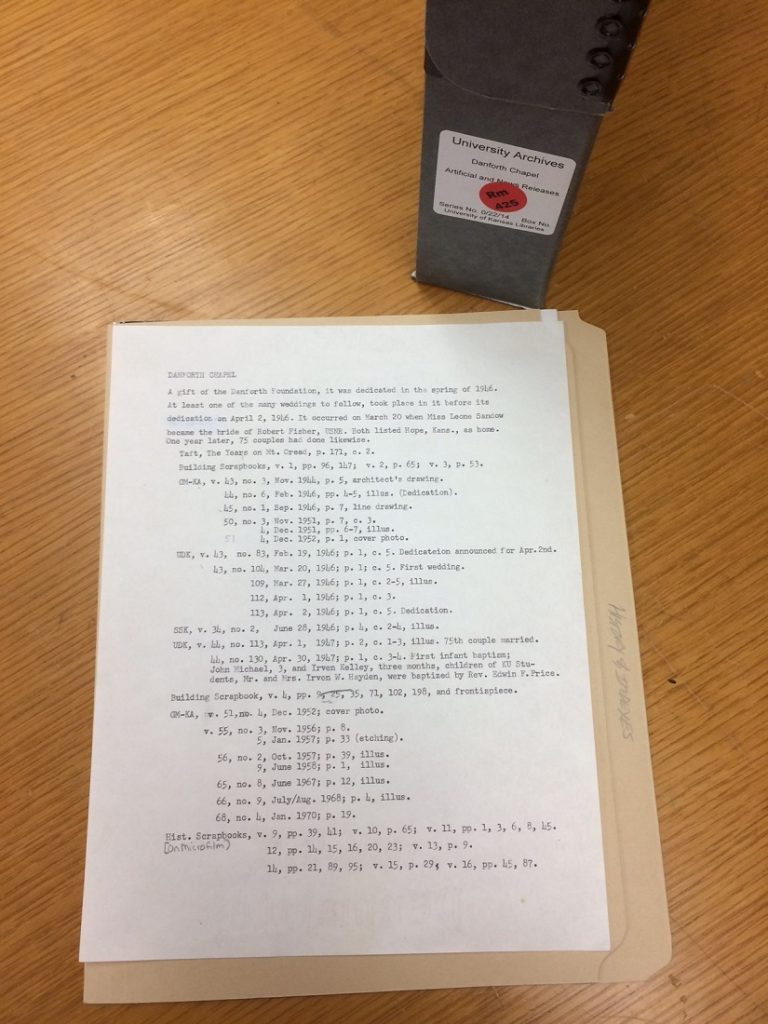

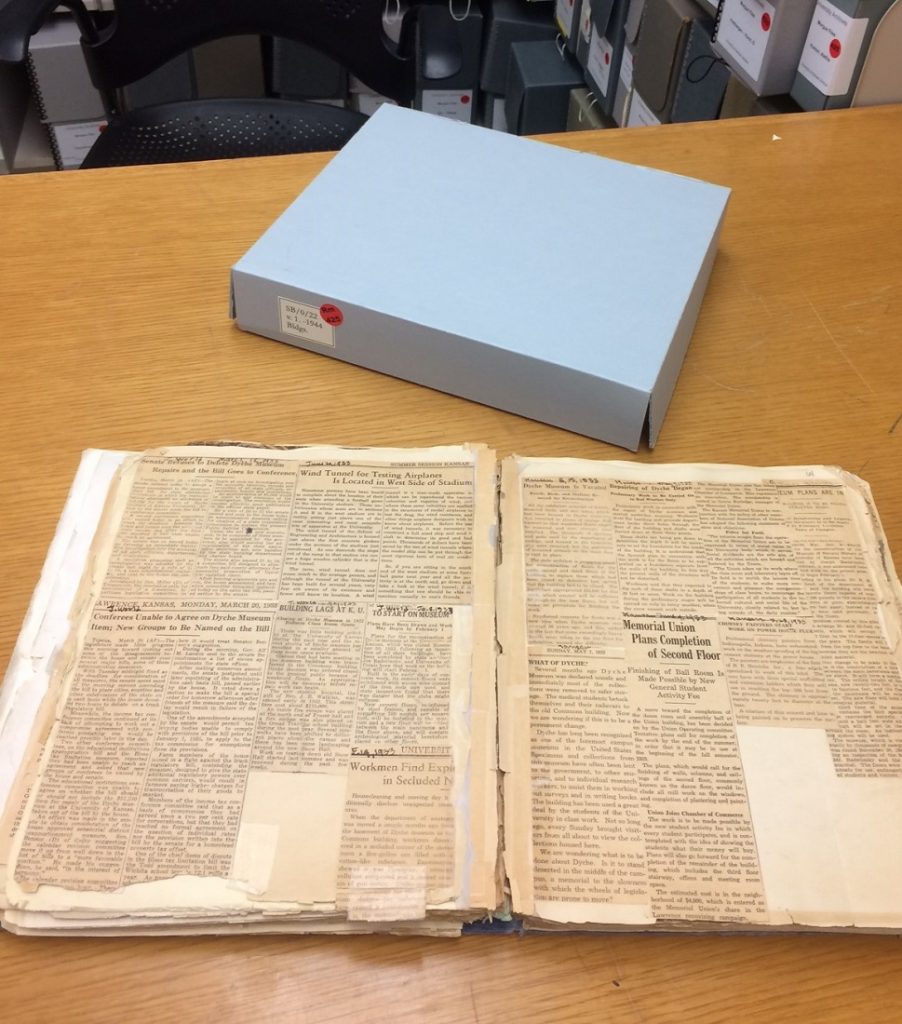

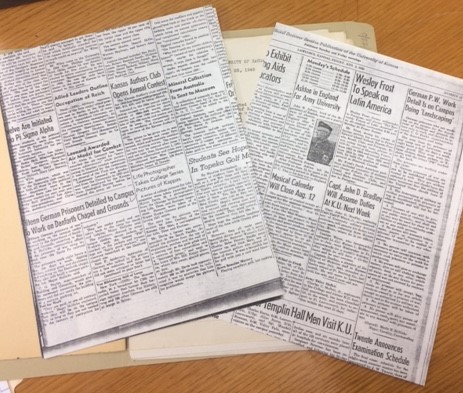

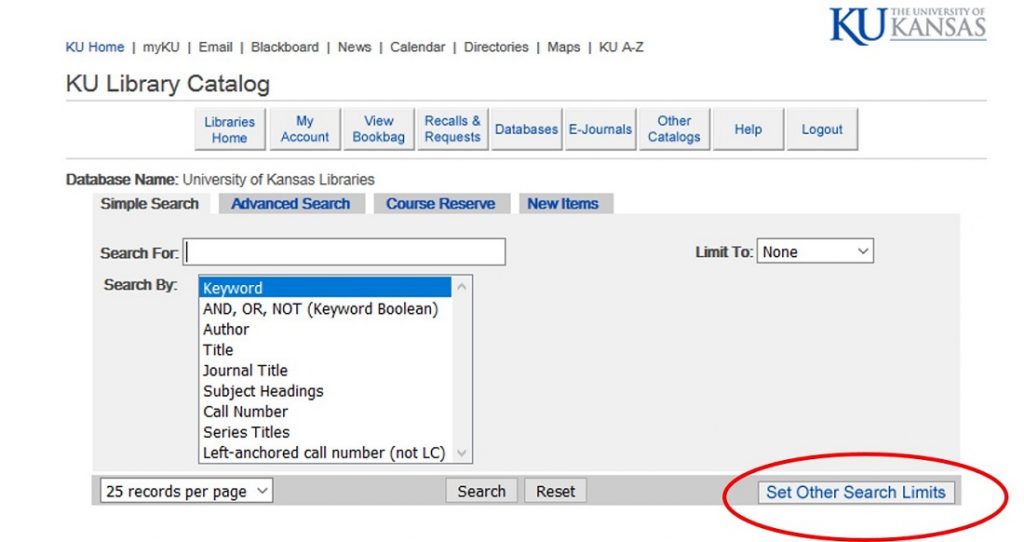

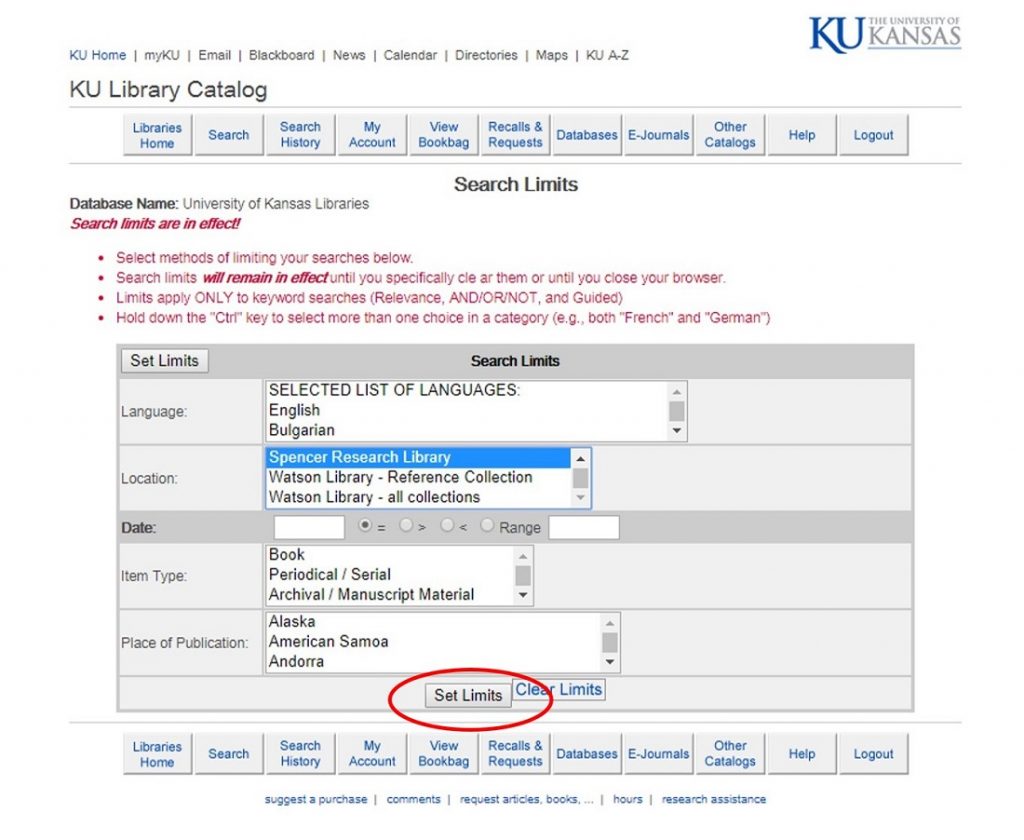

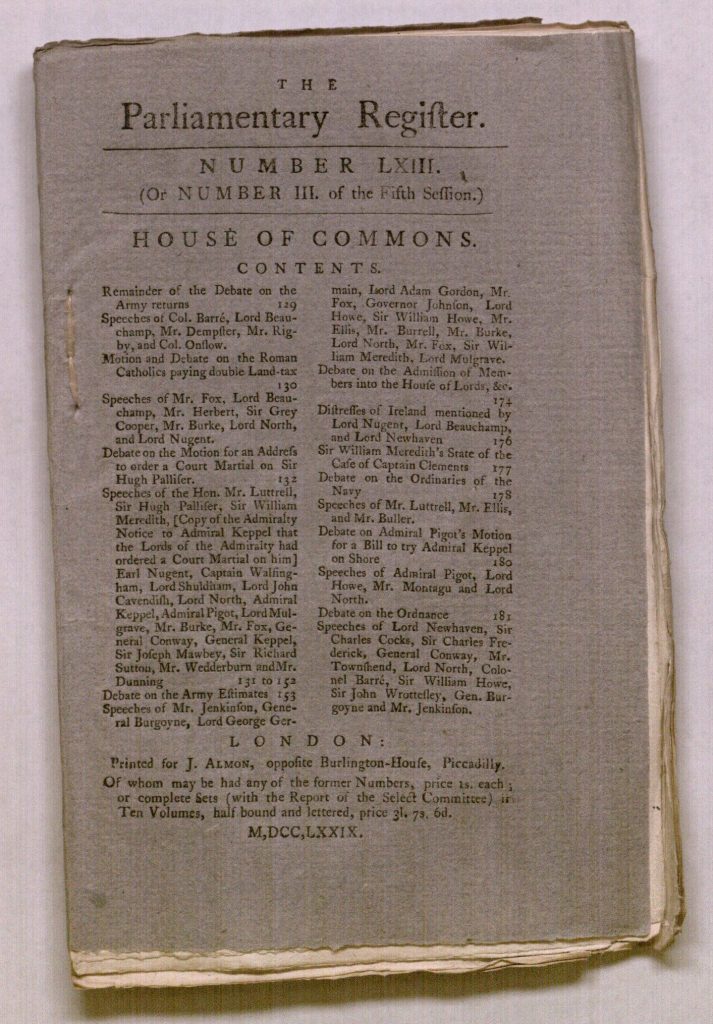

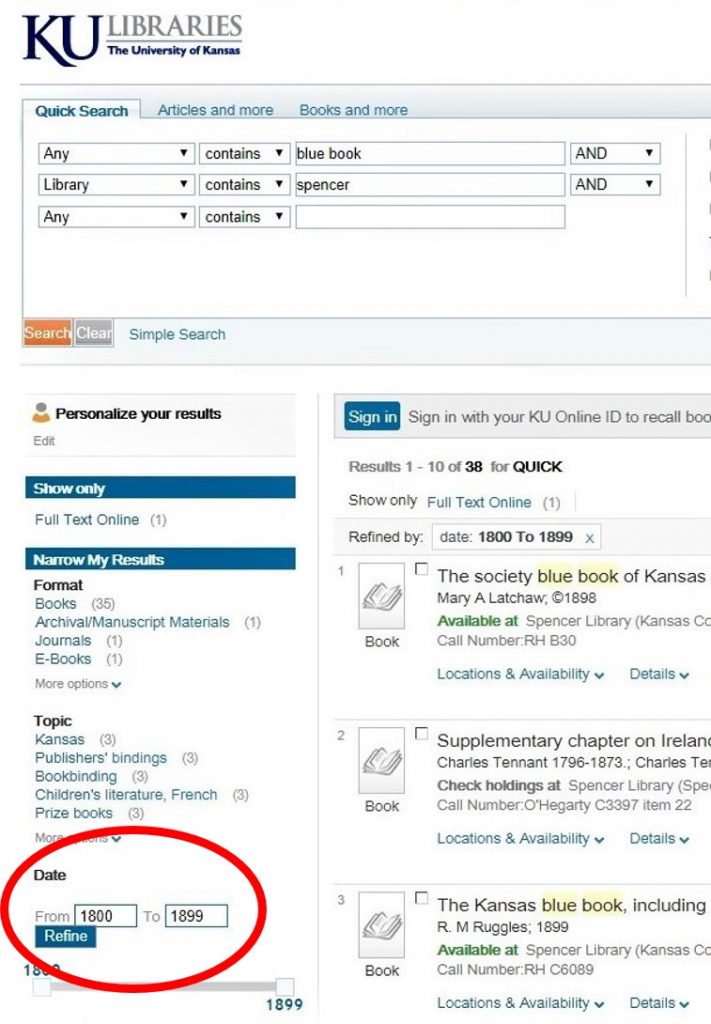

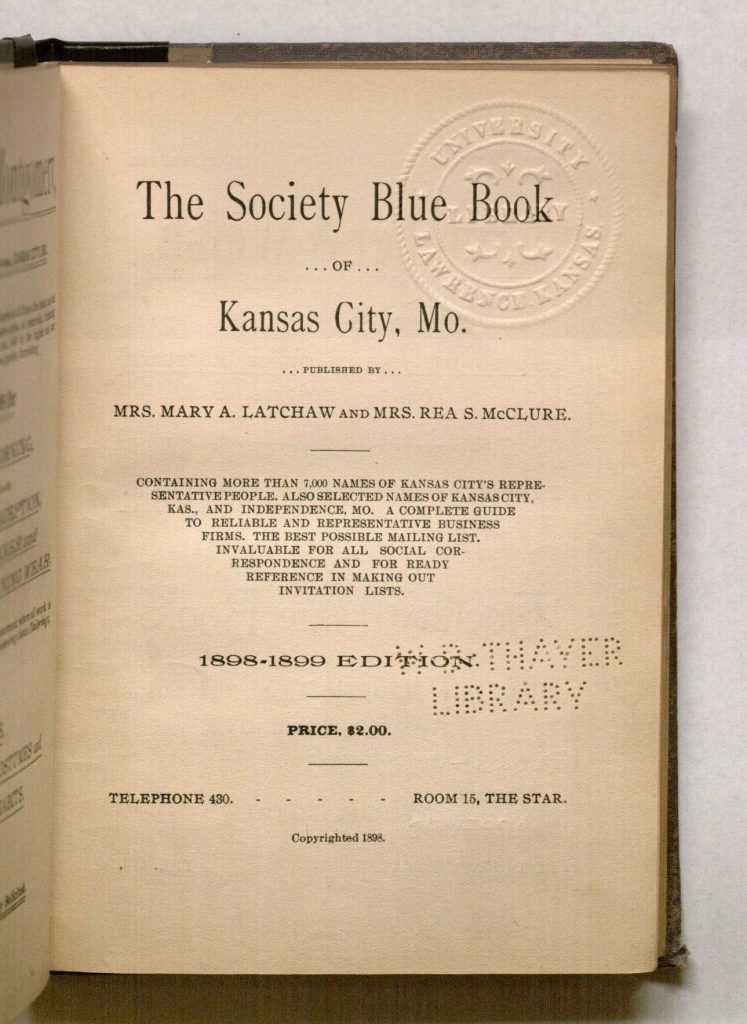

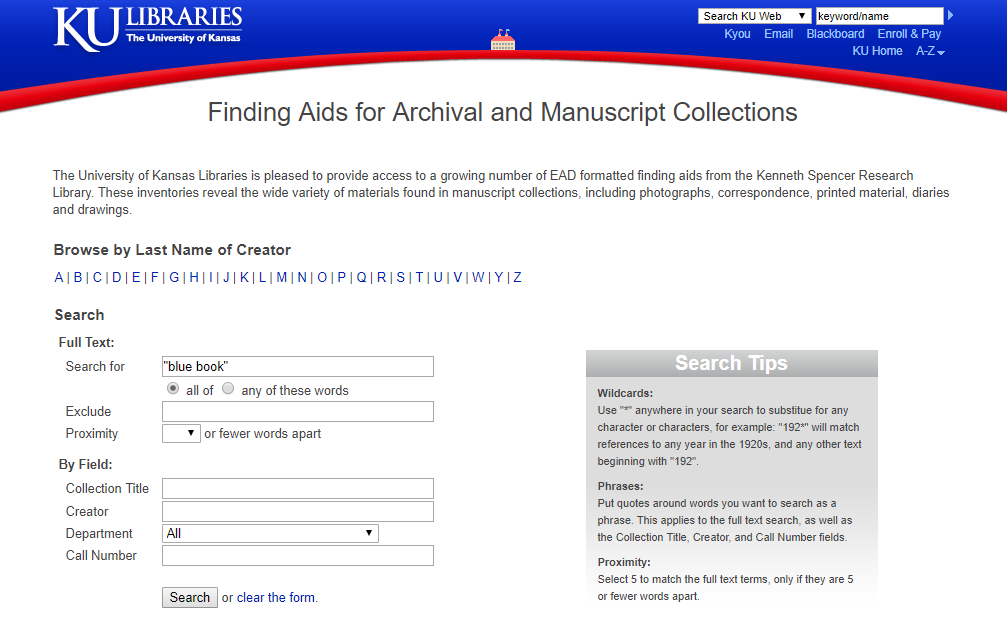

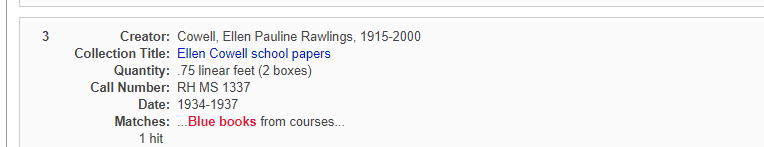

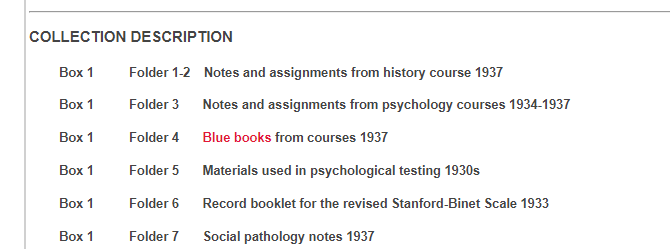

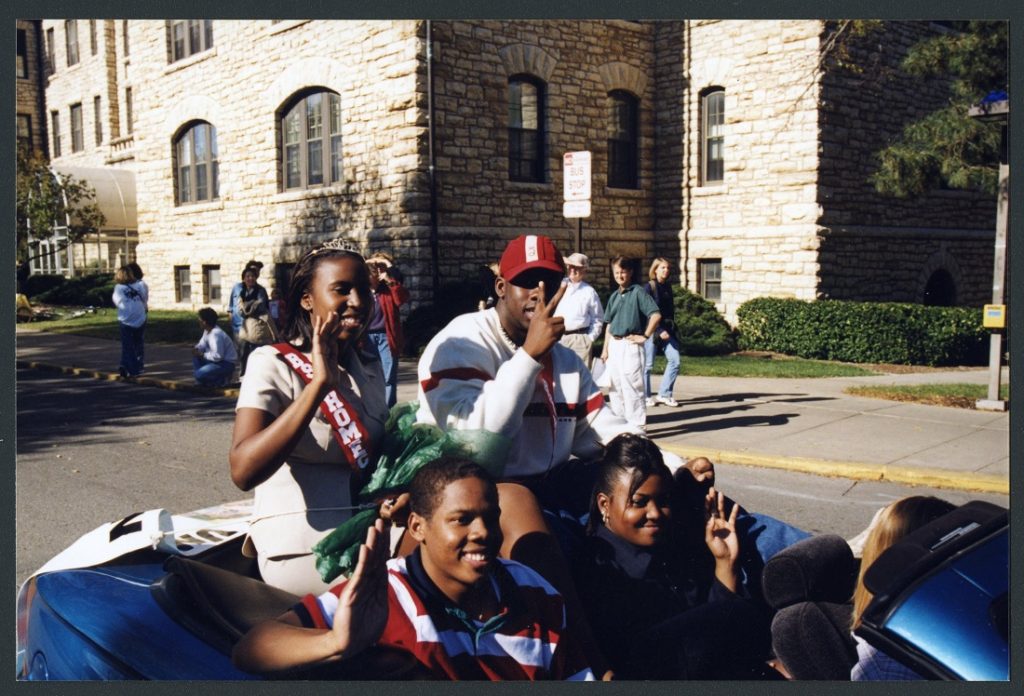

These are just a few of the comments I heard as my English 102 students (mostly freshmen and sophomores) hunched over folders and boxes from the University Archives about past student life and organizations from the past 100 years at KU. For most of my students, this was their first experience in Spencer Research Library, and this experience with archival documents was new and exciting. Although most professors and graduate students use archives for their own research, undergraduate students are often unaware of why archives exist and how they operate. This past semester, I brought my English 102 students into Spencer Research Library and, with the help of University Archivist Becky Schulte, they got hands-on experience doing exciting research with primary sources from the University Archives.

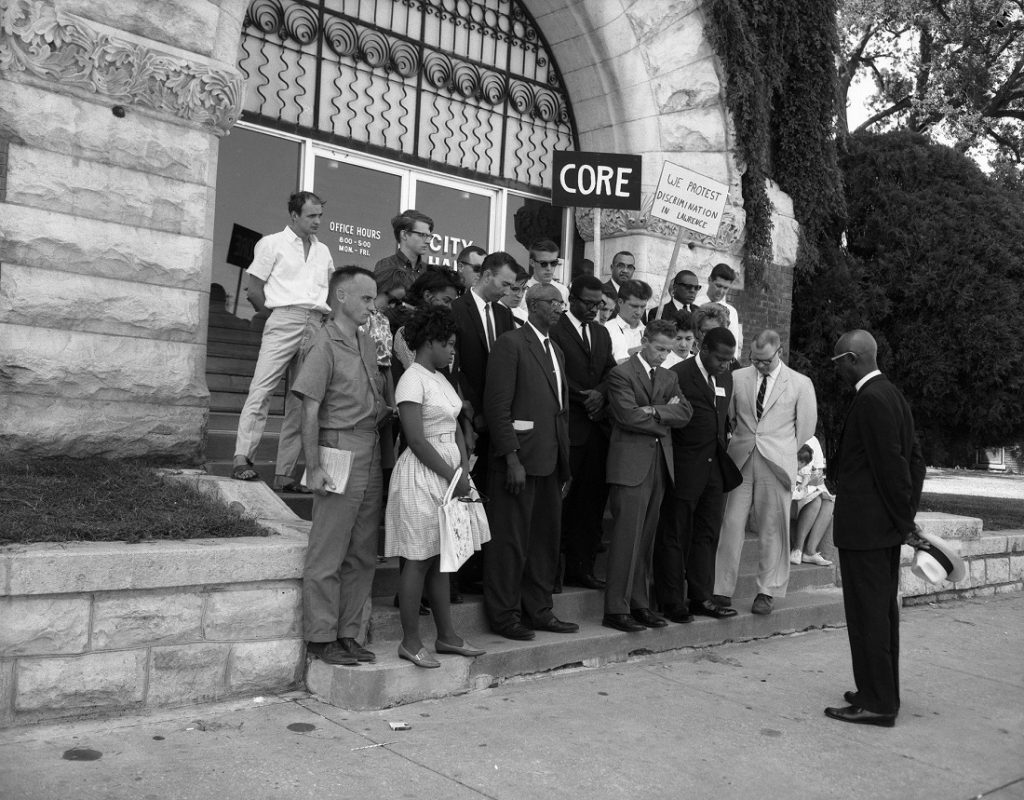

The goal of English 102 is to teach students how to become scholarly writers and researchers and to expose them to scholarly writing genres and research methods. For the past few years, I have always included a unit in my English 102 course that tackles debates and issues in higher education. I want my students to consider the point of their college education as well as learning about issues such as the adjunct crisis, student debt, academic freedom, and increasing administrative oversight. One of the major issues that my students enjoy debating and discussing is student activism. Many students hold the misconception that college campuses have recently become political spaces in just the past five years, yet after diving into the University Archives, we can see that universities and colleges have always been spaces that reflect and respond to the opinions, needs, desires, and politics of its students.

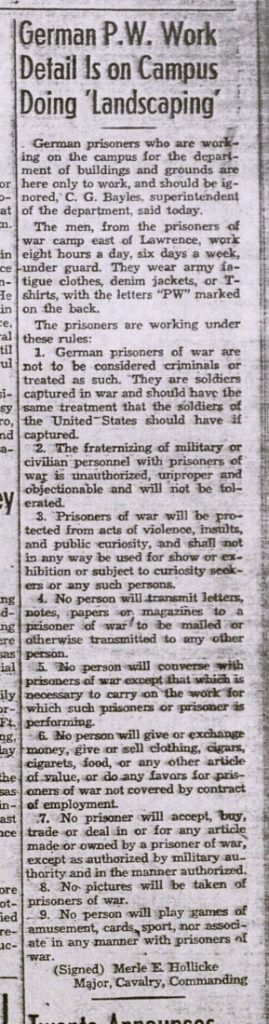

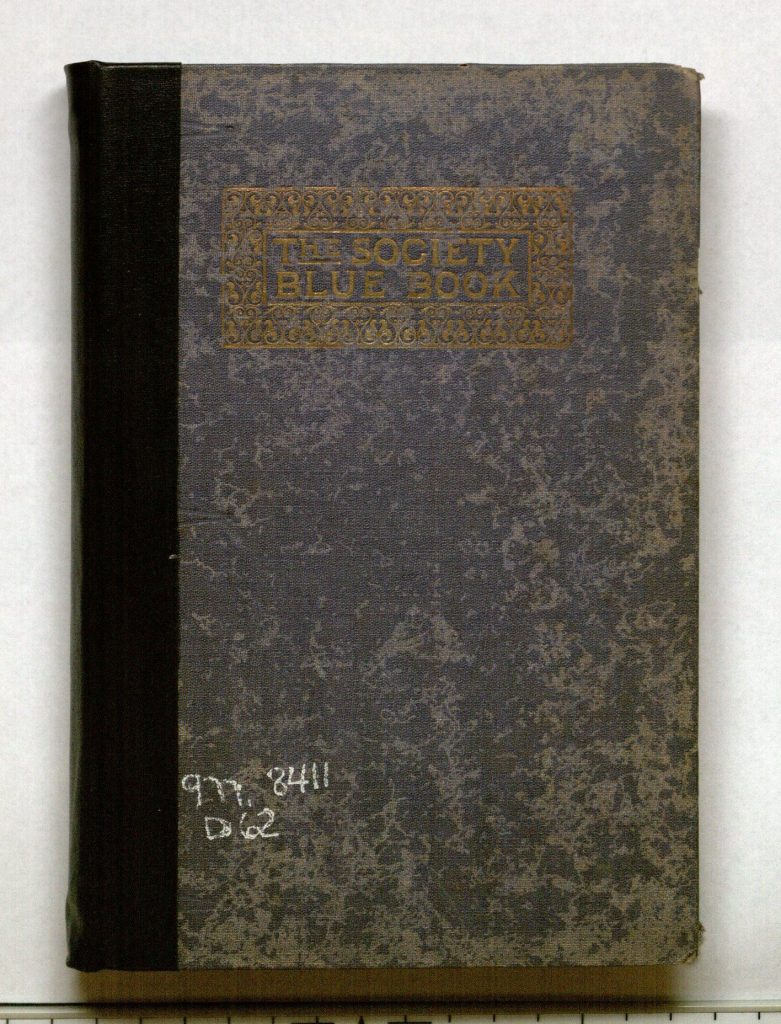

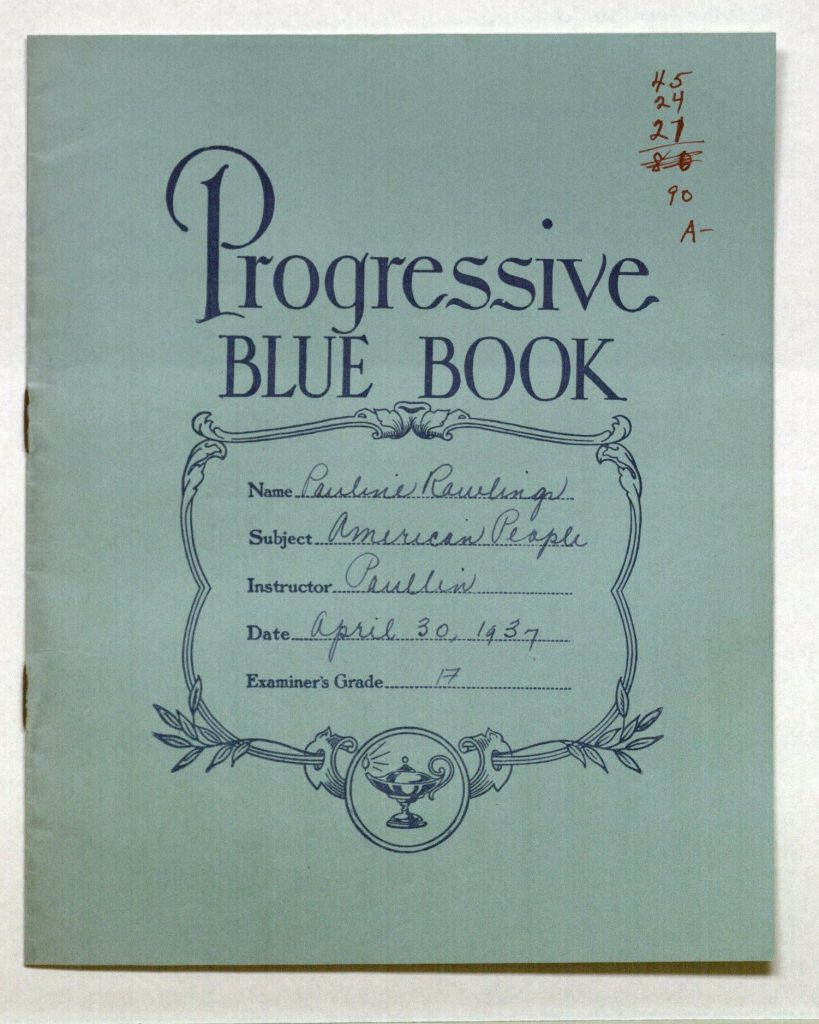

For this assignment, each student was responsible for learning about their chosen KU student organization through archival materials, and they shared their findings with their classmates through presentations that highlighted a particular object from the archive. By examining both the mundane documents of past student life organizations and the media coverage of former student activist groups, my students discovered the lives of past KU students.

Taking all of the student presentations as a whole, the University Archives depict KU’s rich and vibrant history featuring passionate, curious, and community-orientated students. The Archives detail the past lives and struggles of KU student activists like the members of CORE, who fought for desegregation in Lawrence. The archival information about groups such as the Black Student Union, the February Sisters, and Students Concerned with Disabilities also serve as a potent reminder of how students can agitate for change within the university. The University Archives also offers a glimpse into the types of communities from athletics (Tau Sigma [Dance] and Sasnak) to events (KU Medieval Society and KU Home Economics Club) to specialized studies organizations (Graduate Math Women and Wives and the Cosmopolitan Club) that students have made possible throughout KU’s history. My students finished their time in Spencer Research Library not only knowing the basics of how to use archival sources, but also having a larger sense of how their own time at KU will contribute to a long tradition of student life. Many of them noted how much they enjoyed working with primary documents and how they hoped they would be able to return to Spencer Research Library for work in their future classes! (Perhaps there will be a wave of new librarians and archivists in the next four years? Hopefully!)

Personally, I want to give a big thank you to everyone in Spencer Research Library who helped my English 102 students during this process, and a very special thank you for Becky Schulte, without whom these projects could not have happened.

Hannah Scupham, M.A.

University of Kansas Doctoral Candidate, English Literature

Chancellor’s Fellow

Lilly Graduate Fellow