The Roots of Public Education in Lawrence, Kansas

August 14th, 2018If it’s August, then it must be time for school to resume!

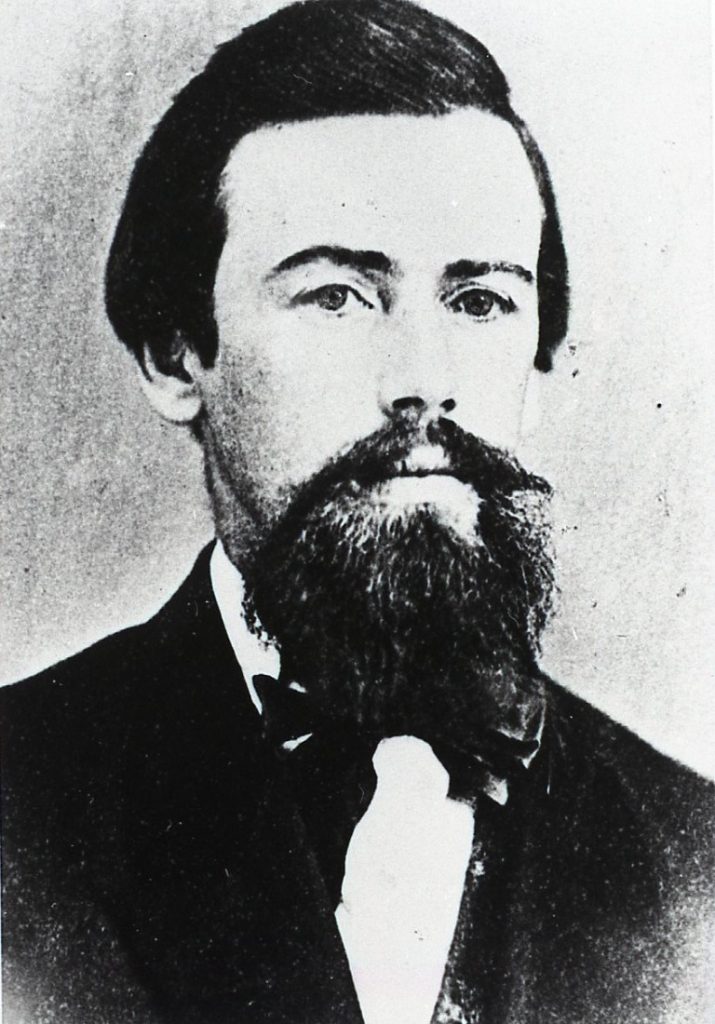

The earliest settlers in what would become Lawrence, Kansas, also wanted school to begin, and as quickly as feasibly possible. The first immigrant party arrived at the town site in August 1854. It was made up of twenty-nine men, all members of the New England Emigrant Aid Company, the mission of which was to ensure that slavery would be illegal in Kansas when it became a state. Specifically written into their original petition was the provision that immigrants coming to Kansas Territory would be provided with public education. True to their word, Lawrence’s founders held the first public classes on January 15, 1855, just five months after their arrival. Edward P. Fitch of Hopkinton, Massachusetts, was the first teacher. Estimates of the number of students in that first class vary between eight and twenty.

Edward P. Fitch, the first teacher in Lawrence, undated. Photo courtesy

of the Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History.

Used with permission from Roger Fitch. Click image to enlarge.

The second teacher was Kate Kellogg, and unfortunately no photo of her is available. Kate returned east after her marriage. She was followed by Lucy Wilder, who held a teaching position in Lawrence for many years. Lucy came to Kansas in 1855 with her father, Abram Wilder.

Lucy Wilder, the third teacher in Lawrence, undated. Lawrence Photo Collection.

Call Number: RH PH 18 K:140. Click image to enlarge.

The first public high school in Kansas was Quincy School, established in Lawrence in March 1857. The school building was constructed ten years later at 11th and Vermont Streets. It was possibly named in honor of Edmund Quincy, a benefactor of the New England Emigrant Aid Company. By 1876 this high school was one of four university-accredited schools in the state.

Quincy School, undated. Photo in Lawrence, Douglas County, Kansas:

An Informal History by David Dary, page 272. Call Number: RH D9258.

Credited to the Kansas Historical Society. Click image to enlarge.

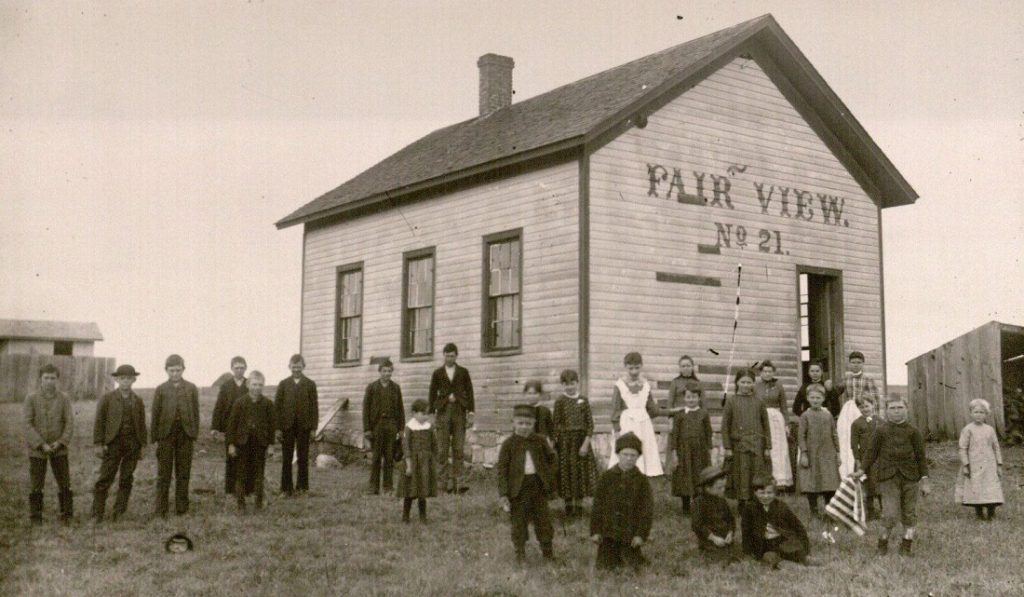

In addition to the schools located within the city limits of Lawrence, there have been as many as eighty-three rural schools located throughout Douglas County. With a few exceptions, most were one-room buildings that served as community centers and church meeting places as well as classrooms. The last rural school, Twin Mound No. 32, closed its doors in 1966, more than one hundred years after the first school opened.

Burnette School No. 62, undated. Lotta Watson, teacher. Shane-Thompson

Photo Collection. Call Number: RH PH 500.1:47. Click image to enlarge.

Crowder School No. 69, undated. Jesse Ady, teacher. Shane-Thompson

Photo Collection. Call Number: RH PH 500.1:60. Click image to enlarge.

Fairview School No. 21, undated. Shane-Thompson Photo Collection.

Call Number: RH PH 500.1:58. Click image to enlarge.

Kaw Valley School No. 12, undated. Maryane Brune, teacher. Shane-Thompson

Photo Collection. Call Number: RH PH 500.1:62. Click image to enlarge.

Undersheriff Charles Edmondson helps children cross Highway 40-59 near Teepee Junction,

White School, District 61, September 14, 1955. Lawrence Journal-World Photo Collection.

Call Number: RH PH LJW 9.14.55. Click image to enlarge.

Kathy Lafferty

Public Services

SOURCES CONSULTED:

Crafton, Allen. Free State Fortress: The First Ten Years of the History of Lawrence, Kansas. Lawrence: The World Company, 1954. Call Number: UA C79.

Daniels, Goldie Piper. Rural Schools and Schoolhouses of Douglas County, Kansas. Baldwin City, Kansas: Telegraphics, 1975? Call Number: RH D5195.

Dary, David. Lawrence, Douglas County, Kansas: An Informal History. Lawrence: Allen Books, 1982. Call Number: RH D9258.

Kansas Women Schoolteachers Project records. Call Number: RH MS 872. Kansas Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library.