Marvelous Medieval Marginalia

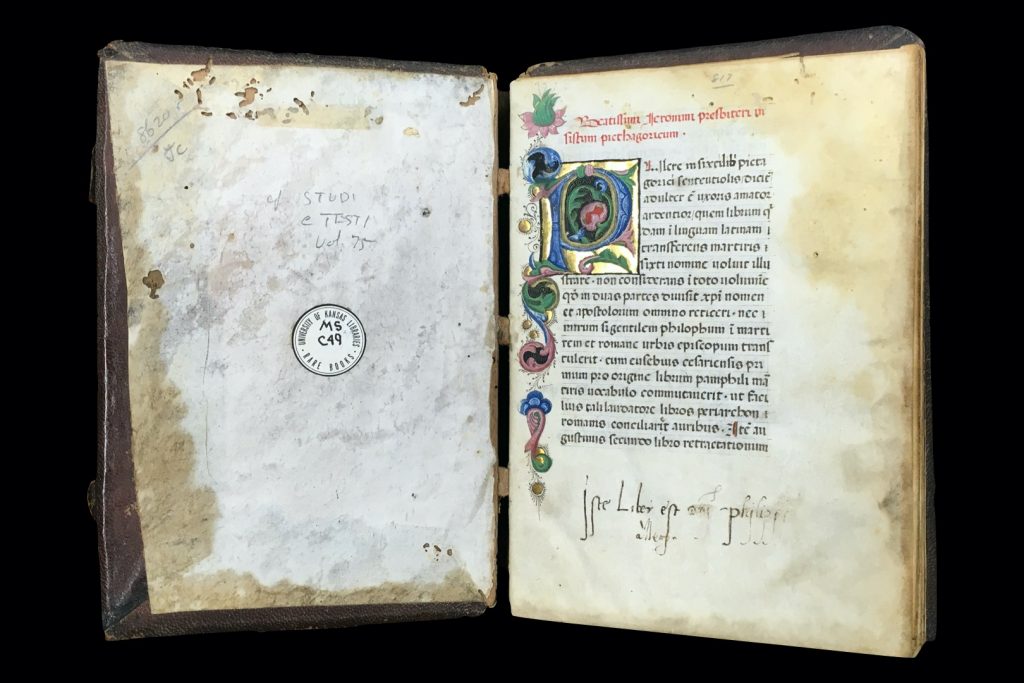

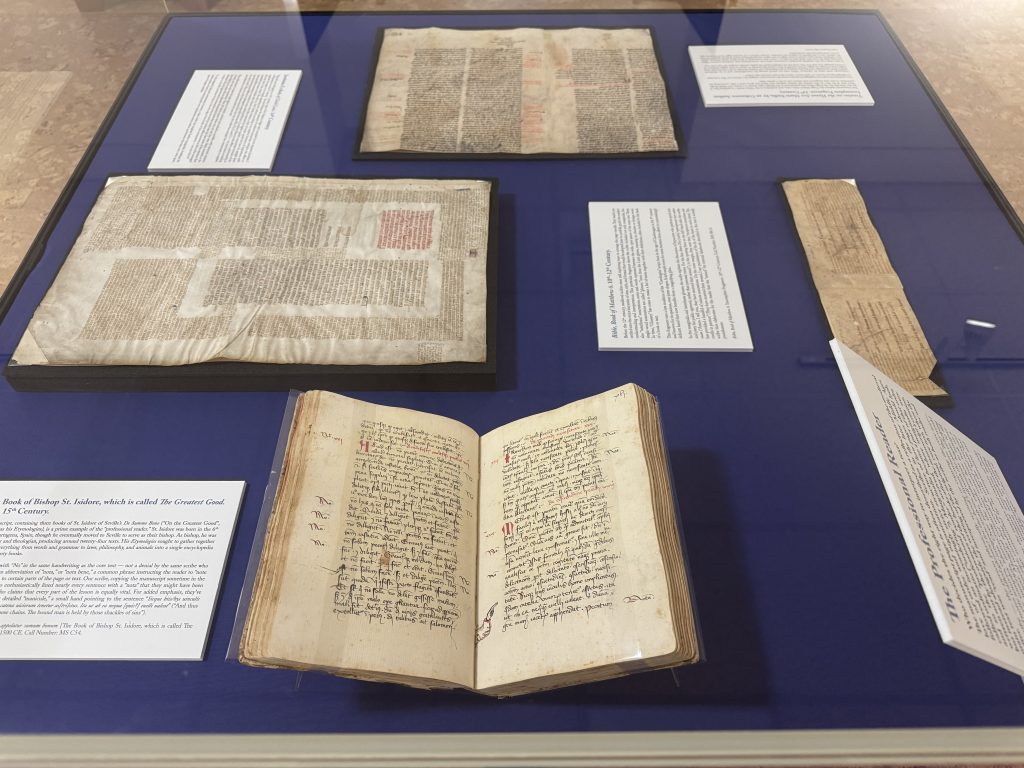

March 19th, 2025One of the most fascinating things about medieval manuscripts is that every copy is unique and individual. Because scribes wrote manuscripts by hand, no two copies are identical. On March 8th, Kenneth Spencer Research Library opened Marvelous Medieval Marginalia, an exhibit that celebrates the unique and the individual, the best parts of medieval manuscripts, and the scribes, readers, and owners who had a hand in transforming texts over time. It’s dedicated to the voices of not necessarily the great and influential authors and artists of old but to a quieter subset who aren’t always given the attention they deserve – the readers, the imaginers, and doodlers across centuries.

The exhibit focuses on marginalia. From the Latin for literally just “things in the margins,” marginalia can encompass many things, from formally executed illustrations meant to enhance the manuscript into a work of art to notes and annotations. We tend to think of books as static or frozen in time, but through marginalia and readers, they were often amorphous and ever-changing, shaped and reshaped by their owners over decades and centuries. Medieval readers were not merely passive consumers of manuscripts; they thought about and engaged with their texts, argued and agreed, and added their thoughts. And their relics are preserved in the notes they left behind, capturing their fleeting thoughts in amber for us to enjoy centuries later.

With annotations, we can see what people actually thought about the texts they read. They let us see where readers denied or disagreed with the original manuscript – as with this manuscript copy of Lactantius’ Divine Institutes, a defense of Christianity and a refutation of Greek and Roman polytheism.

![Image of a detail from a manuscript copy of Lactantius’ Divinae Institutiones [The Divine Institutes], Italy, ca. 1400-1500 CE., with manuscript notes in the margin.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Image-2-MS-C61-1024x405.jpg)

An early reader has added the note “falsum” or “false” while striking lines through parts of the text – potentially either disagreeing with the text itself or perhaps claiming it was spurious and misattributed. Where readers’ notes give us insight into the sometimes-critical thoughts of medieval readers, their doodles provide glimpses into the universal experience of boredom and the creativity it can allow to blossom. With doodles, “the more things change, the more they stay the same.” We doodle just as much today as people did 800 years ago, but what we doodle changes, reflecting the nuances of human culture and identity. It’s a time-honored tradition across the centuries; you’ve likely stuck at least a few notes in the margins of your class assignments or books over the years. Idle doodles encapsulate the wandering thoughts of people from the past as they were when they took quill pen to page.

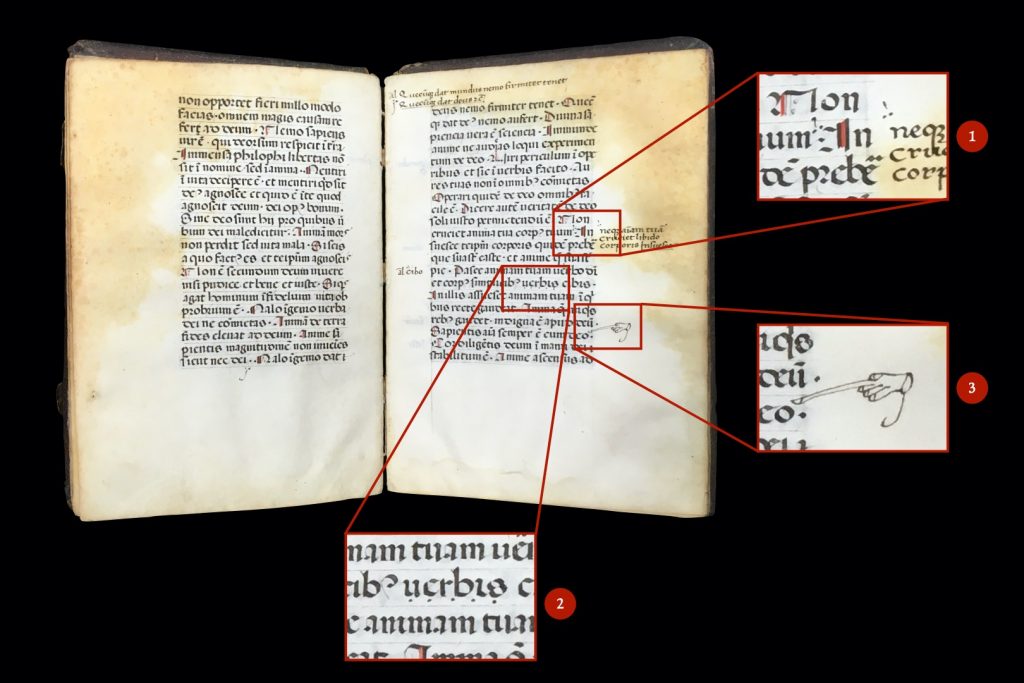

Sometimes, it was the scribes themselves, the people writing and copying the manuscripts for later audiences, who added flares of fun into the margins. Copying manuscripts by hand was often a long and tedious process, taking anywhere from days to months. A certain playfulness to these marginalia emerged when the scribe’s mind and hand wandered. You wind up with texts like MS B15, a collection of Divine Offices, hymns, prayers, and devotional poetry, where the scribe has very diligently copied the text for over 700 pages, all written in the same hand so that you know this is one person scribbling page after page after page. But they’ve broken the tedium by dappling the tops and bottoms of letters with -Picasso-esque caricatures, skewed profile faces wearing silly hats, and the occasional peacock.

![Image of doodles of faces in the margins of Spencer's manuscript copy of Ordinatio totius officii divini secundum usum monasterii Beatae Mariae de Belgentiaco. [A Complete Order of the Divine Offices According to the Use of the Monastery of the Blessed Mary of Beaugency.]. France, 1400-1500.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Image-3-MS-B15-1_red.jpg)

Marginalia can help reveal the silent reader’s voice and how they understood or analyzed texts – but even in the case of drawings and doodles, these weren’t all the product of an idle mind. Often, the doodles in the margins directly responded to and sometimes commented upon the text itself, creating visual commentary that shows how a scribe or reader responded to the work. These are called deliberate or communicative doodles.

Marginalia didn’t end with the advent of print, but they were unquestionably changed by it. In many ways, printing is more rigid than writing a manuscript. You work with a metal frame that limits where letters can fit, the shape of the page and its structure, and all the letters are predetermined shapes carved into small metal pieces that you then reorganize into different words. That rigidity, of course, meant that it was much easier to make literal copies of the text, nearly identical to one another.

While print stole some of the freedom and flexibility of the page and written word, readers continued to imbue their books with their agency and interpretations, even with the radical technological shift. One reader of Agostino Nifo’s A Small Commentary on the Most Accurate Signs of Weather has bestowed nearly every page with minute illustrations connected to the text, highlighting the vibrancy of weather with sketches of animals associated with certain types of weather alongside copious notes, including a doodle of a bat next to Nifo’s claim that when bats fly in a great flock in the evening, it promises a calm, serene night.

![Image of manuscript marginalia, including an image of a bat, in the margins of a 1540 printed copy of De verissimis temporum signis commentariolus [A Small Commentary on the Most Accurate Signs of Weather/Seasons], by Agostino Nifo.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Image-4-MS-B75-p45.jpg)

Manuscripts reflect the medieval mind. Through marginalia, we can see how they organized their thoughts and how they reacted and responded to text and information. In the same way, when you visit an exhibit, you bring your thoughts, experiences, and analyses to the books. As you go through it, you may pick and choose different parts of the exhibit that catch your eye and interest; you may find the exhibit text insightful (or boring!). My exhibit text will tell you what I think is important about materials, but those won’t be the same things that you find interesting or important. With this exhibit, open through July, I invite you to bring your own doodles to our margins – including the exhibit wall text! You’ll see the manuscripts mentioned above, with many more, that all embody the agency and choices of their readers over the centuries. We welcome you to read, think, and doodle about the exhibit (albeit preferably not in our manuscripts). Thank you for being a reader of our exhibits here at Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

Eve Wolynes

Special Collections Curator