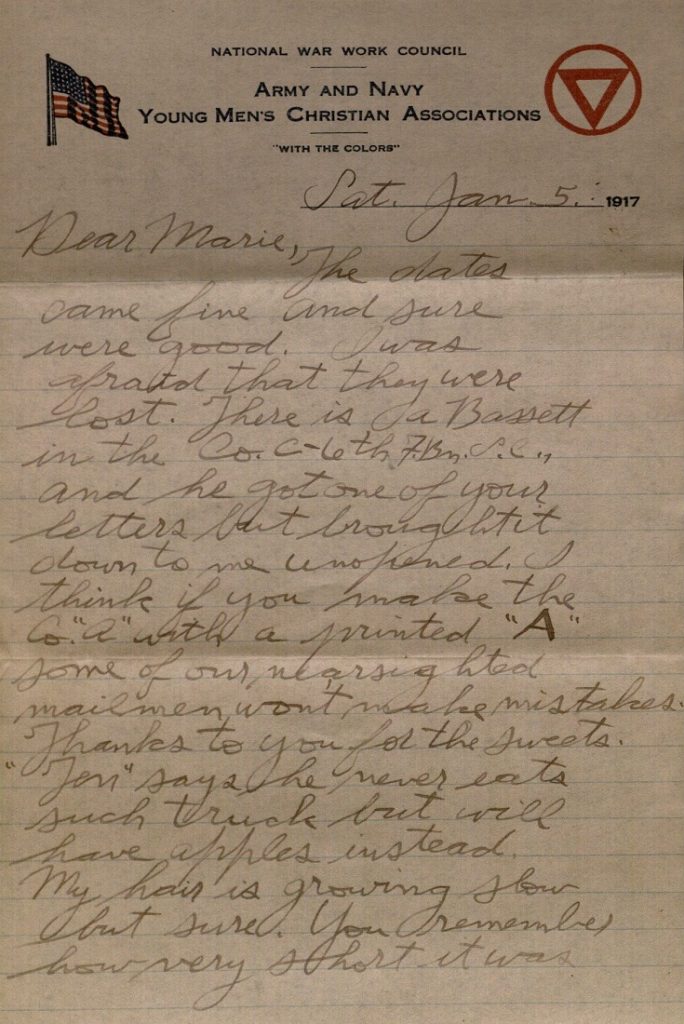

World War I Letters of Forrest W. Bassett: January 22-28, 1918

January 23rd, 2018In honor of the centennial of World War I, we’re going to follow the experiences of one American soldier: nineteen-year-old Forrest W. Bassett, whose letters are held in Spencer’s Kansas Collection. Each Monday we’ll post a new entry, which will feature selected letters from Forrest to thirteen-year-old Ava Marie Shaw from that following week, one hundred years after he wrote them.

Forrest W. Bassett was born in Beloit, Wisconsin, on December 21, 1897 to Daniel F. and Ida V. Bassett. On July 20, 1917 he was sworn into military service at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri. Soon after, he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for training as a radio operator in Company A of the U. S. Signal Corps’ 6th Field Battalion.

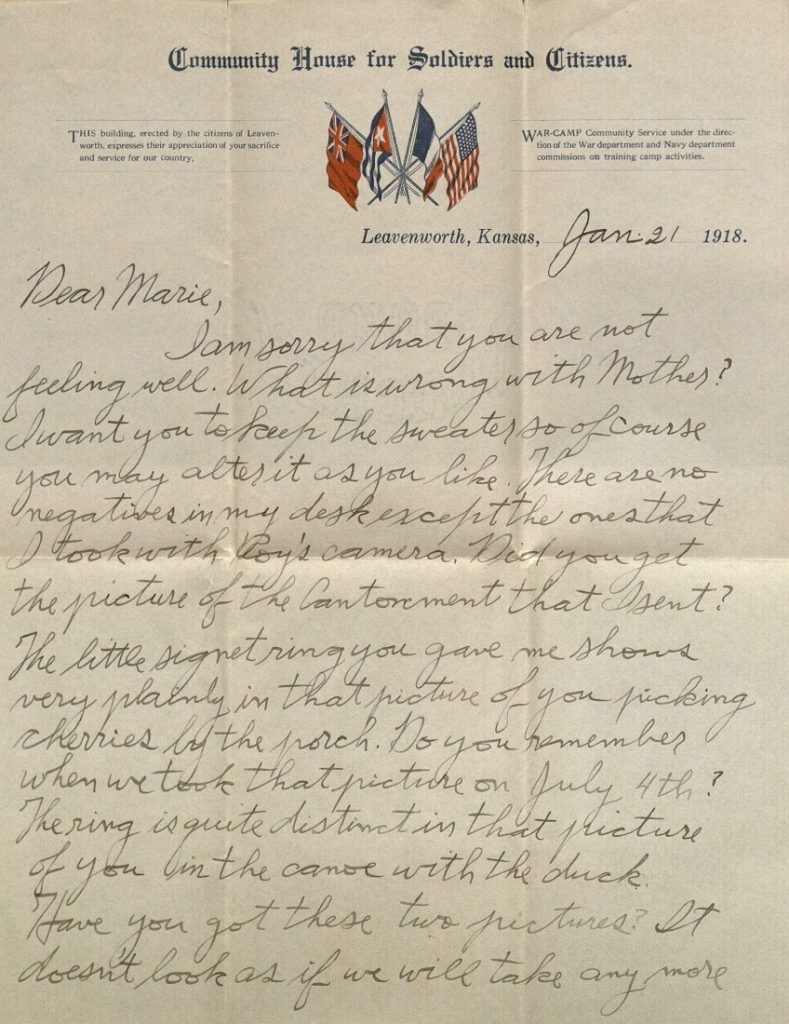

Ava Marie Shaw was born in Chicago, Illinois, on October 12, 1903 to Robert and Esther Shaw. Both of Marie’s parents – and her three older siblings – were born in Wisconsin. By 1910 the family was living in Woodstock, Illinois, northwest of Chicago. By 1917 they were in Beloit.

Frequently mentioned in the letters are Forrest’s older half-sister Blanche Treadway (born 1883), who had married Arthur Poquette in 1904, and Marie’s older sister Ethel (born 1896).

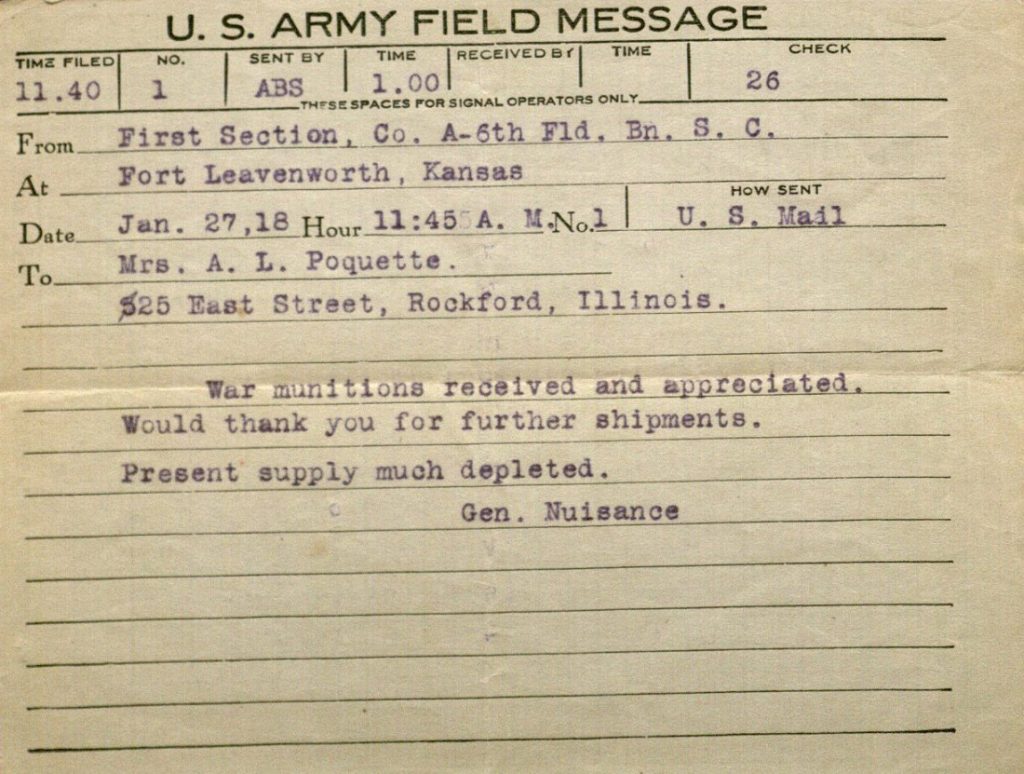

Highlights from this week’s letter include horseback riding (“nearly three weeks of loafing around in the corral made them feel pretty funny”) and guard duty (“All I did Wednesday after 8:30 A:M was to take one of the prisoners from the guardhouse to his Company mess house for dinner. This fellow had a couple pretty serious charges against him”). This week’s letters also include a field message from Forrest (writing as “Gen. Nuisance”) to his sister Blanche, thanking her for the “war munitions.”

Click images to enlarge.

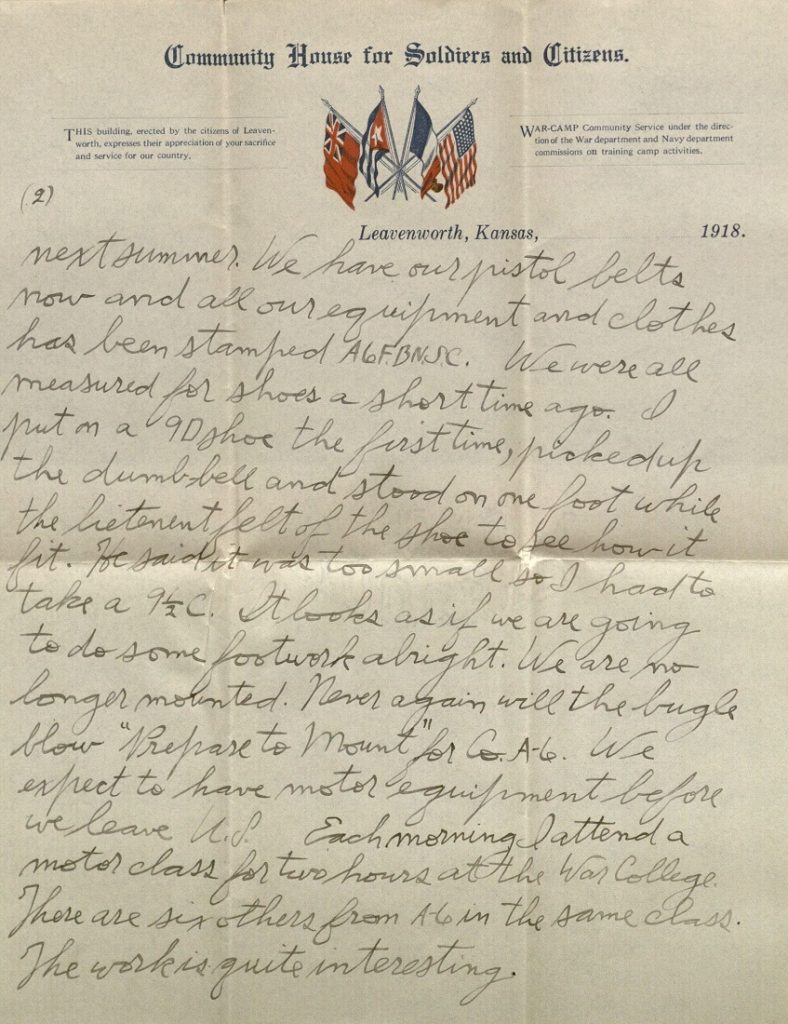

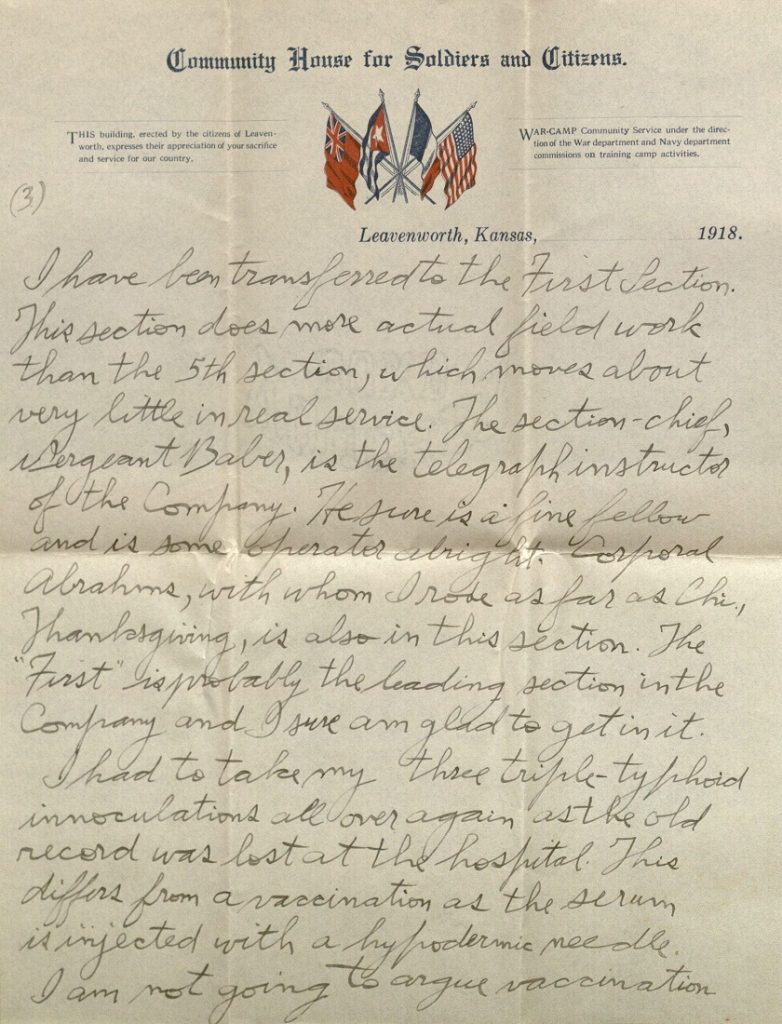

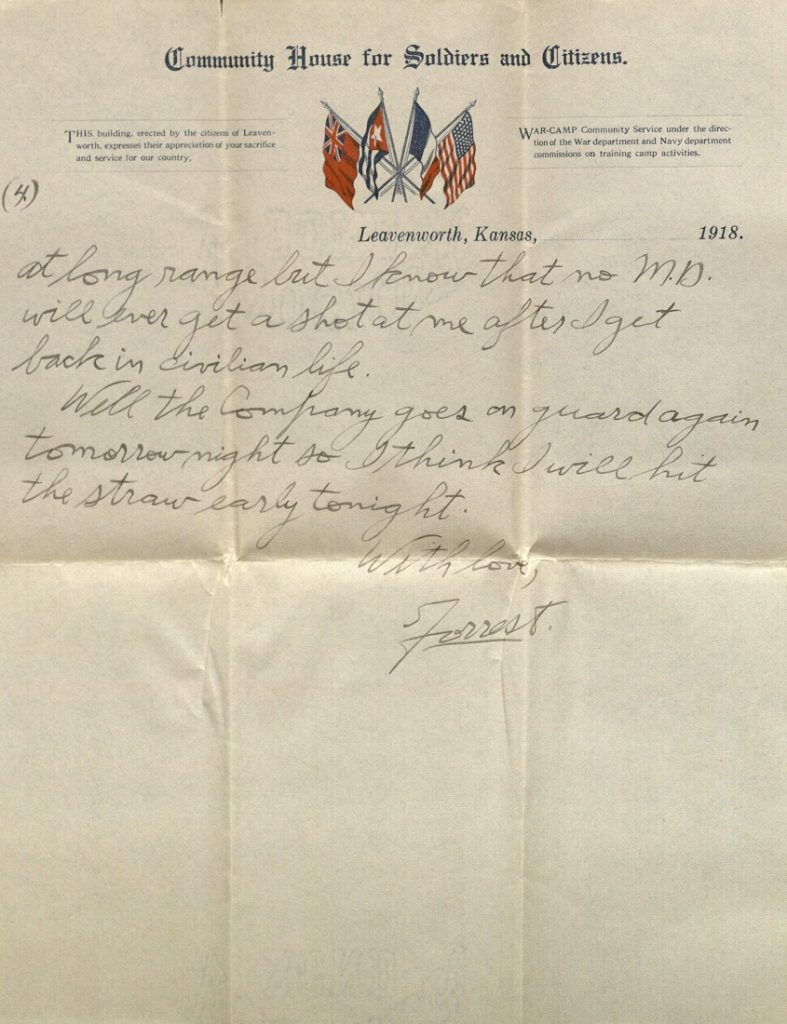

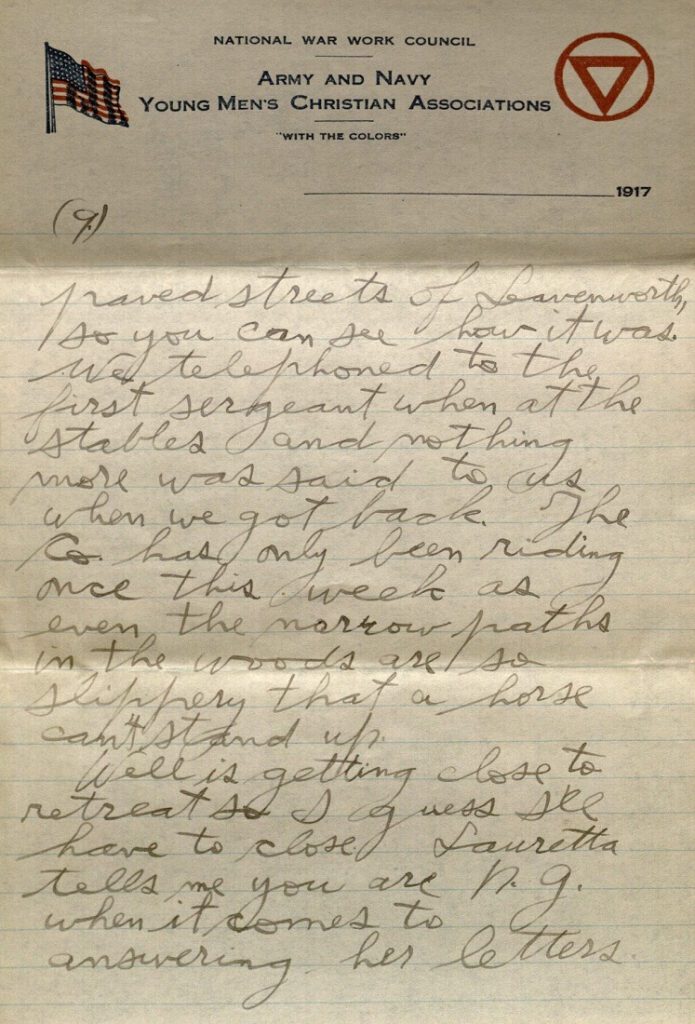

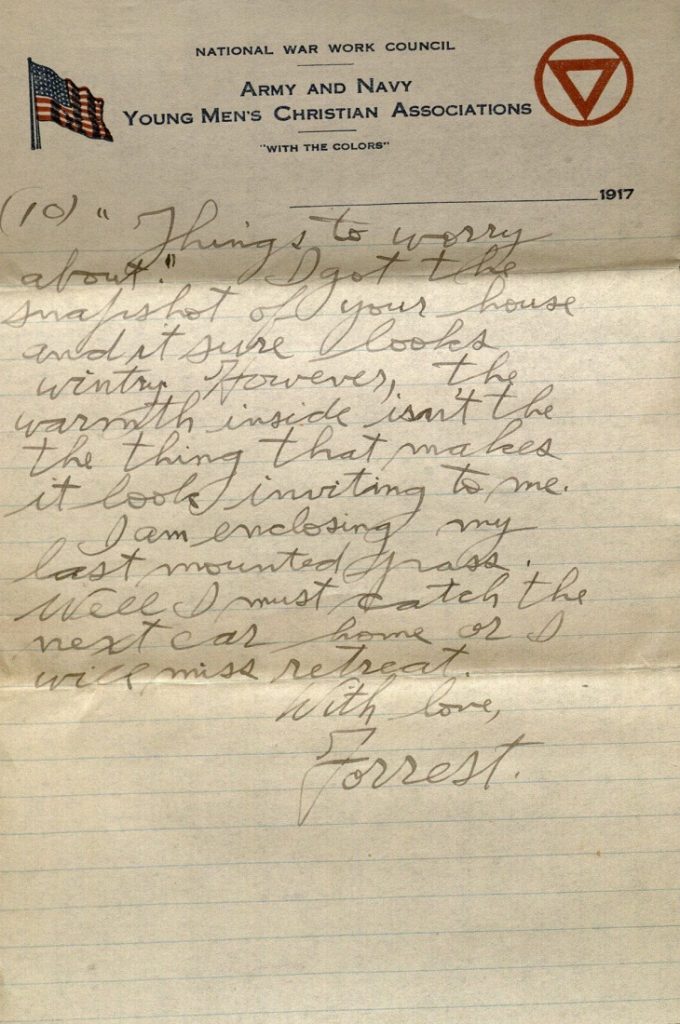

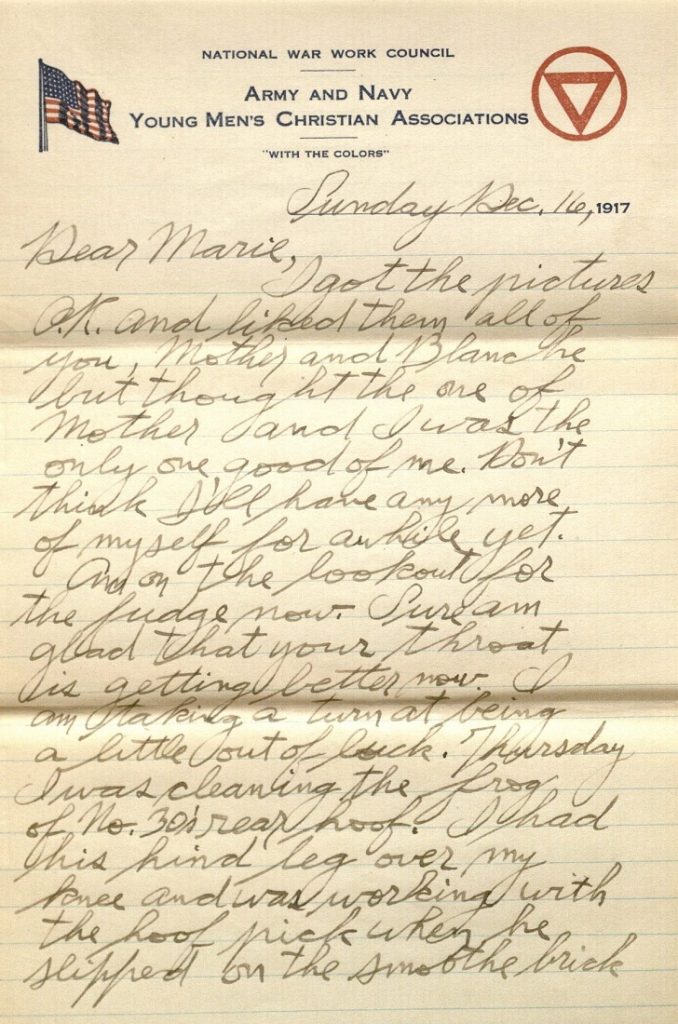

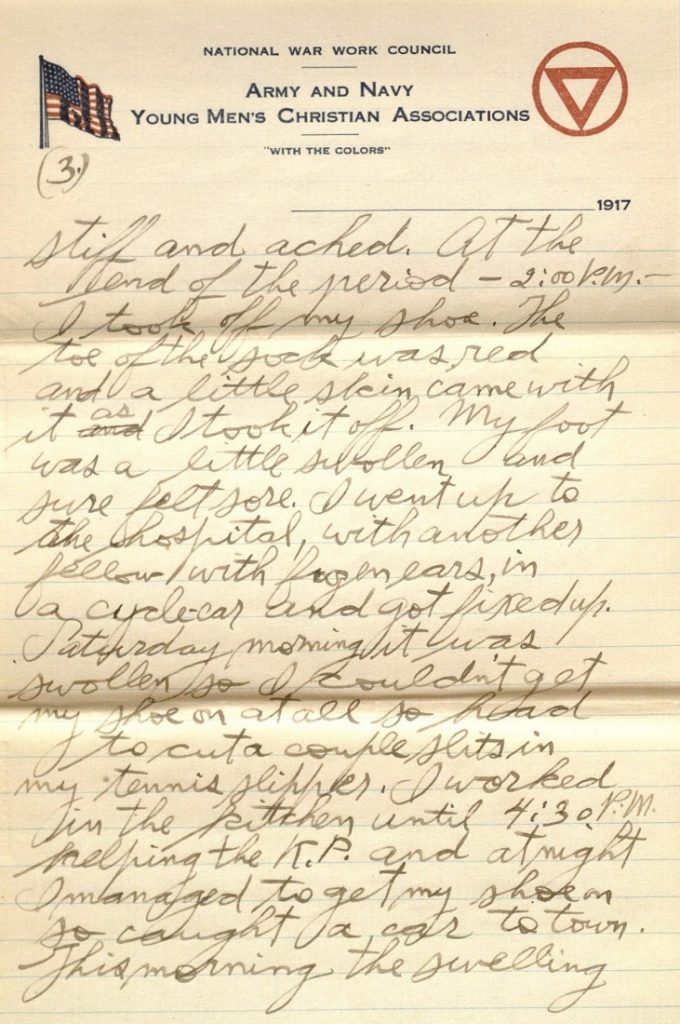

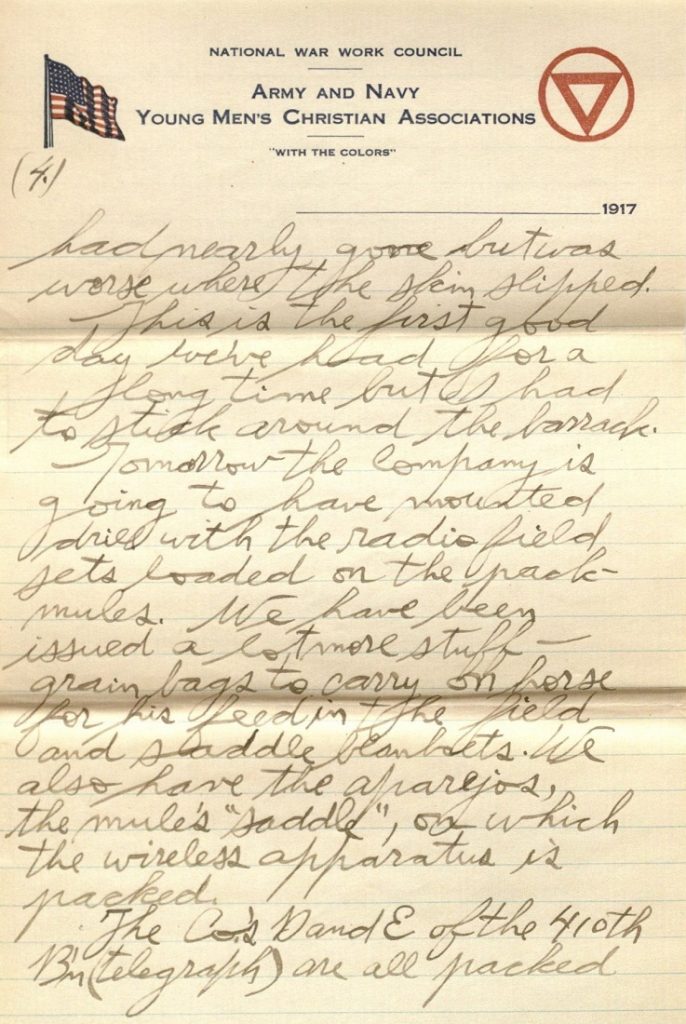

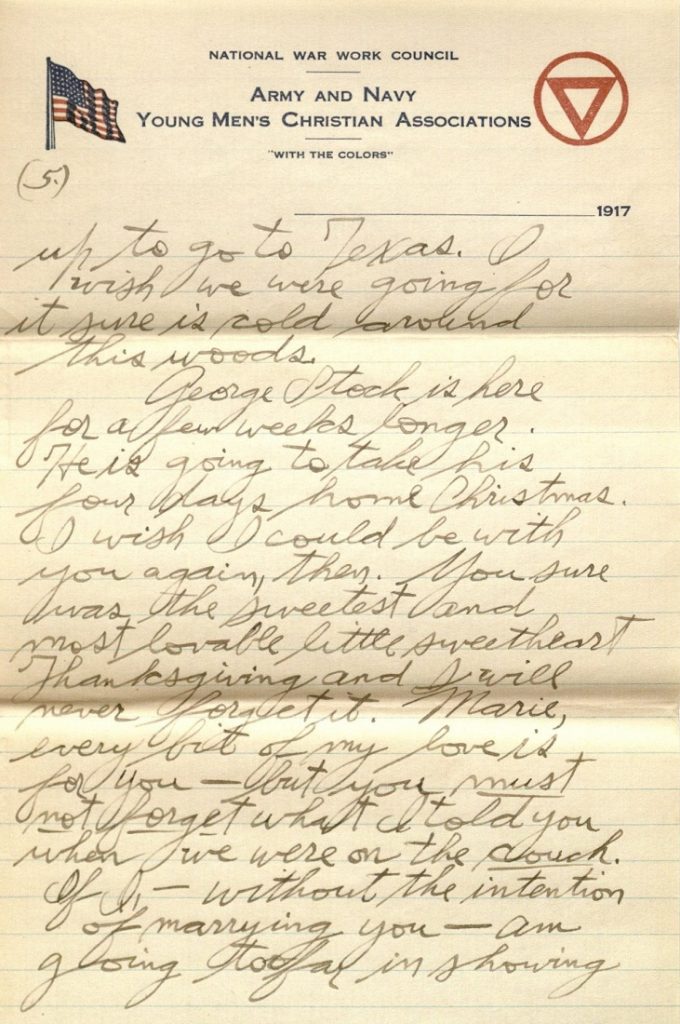

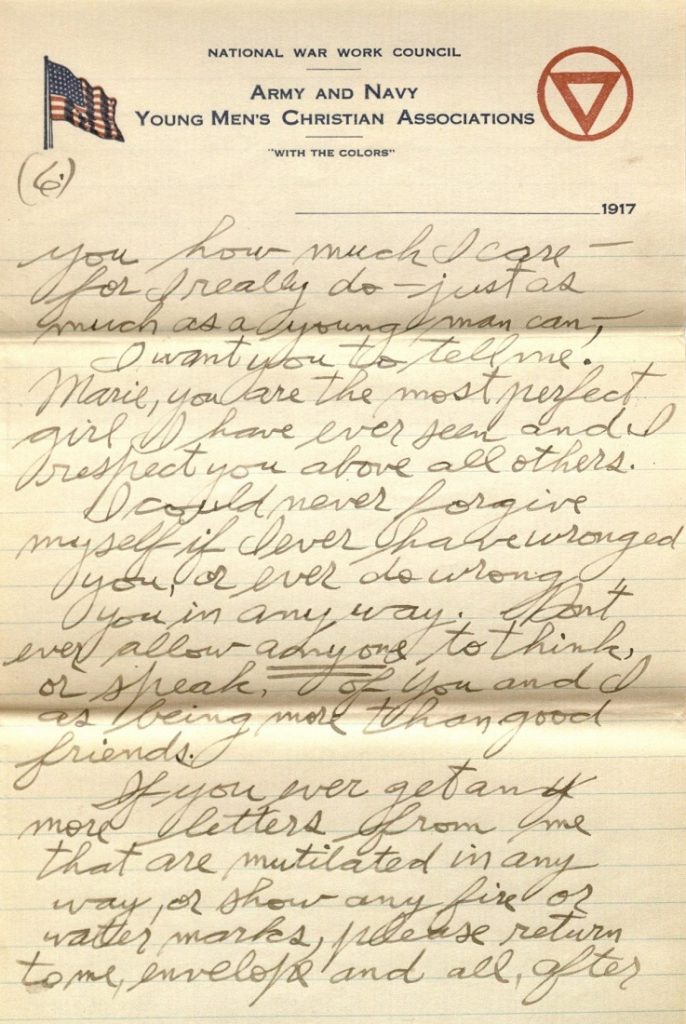

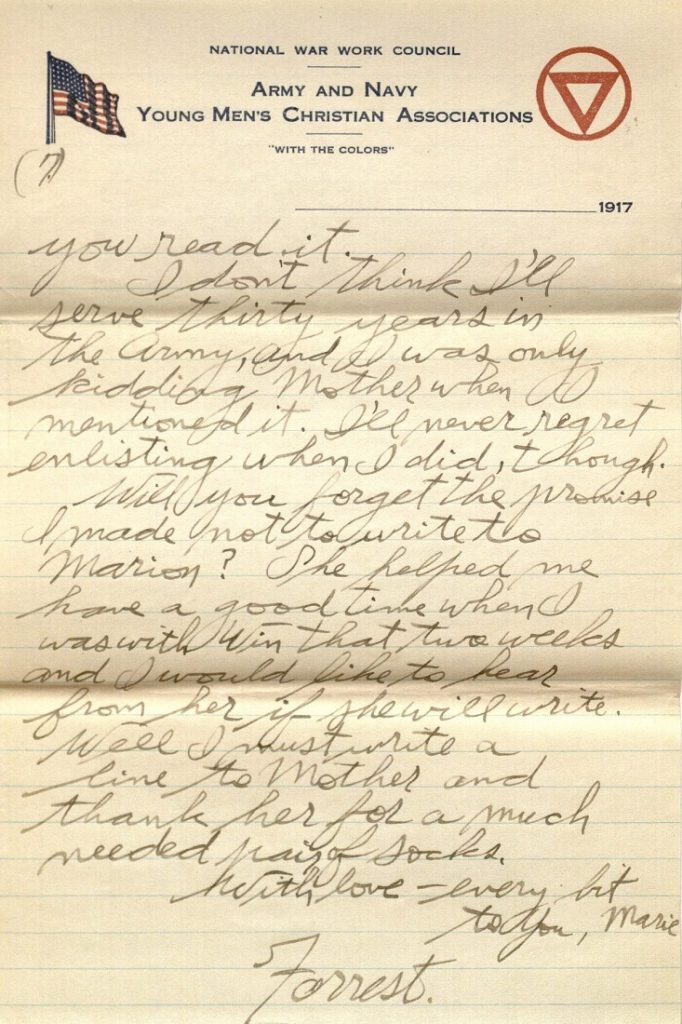

Jan. 27, 1918.

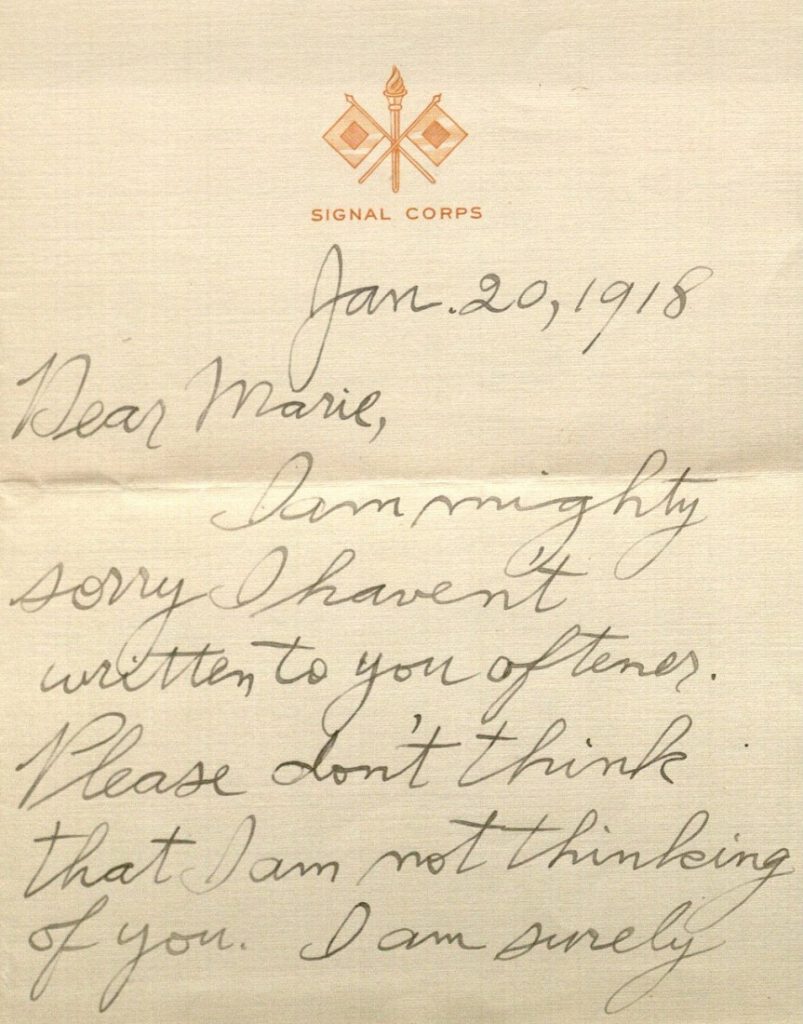

Dear Marie,

Stock has gone to K. City so I came down to the Leav. “Y” to write. I sure was glad to get your letter. Yesterday I tried to bribe the C’p’l in charge of quarters to bring a letter from Beloit with the mail, but even a big slice of Blanche’s cake was not enough.

I am still going to the motor class at the Service School. Have you a picture of the latter?

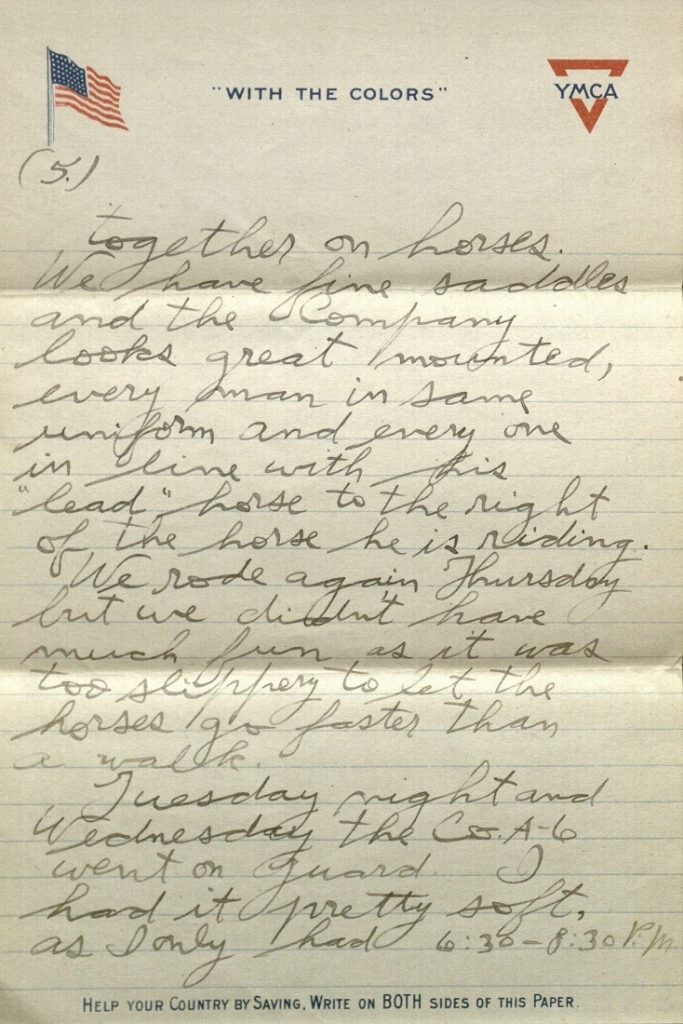

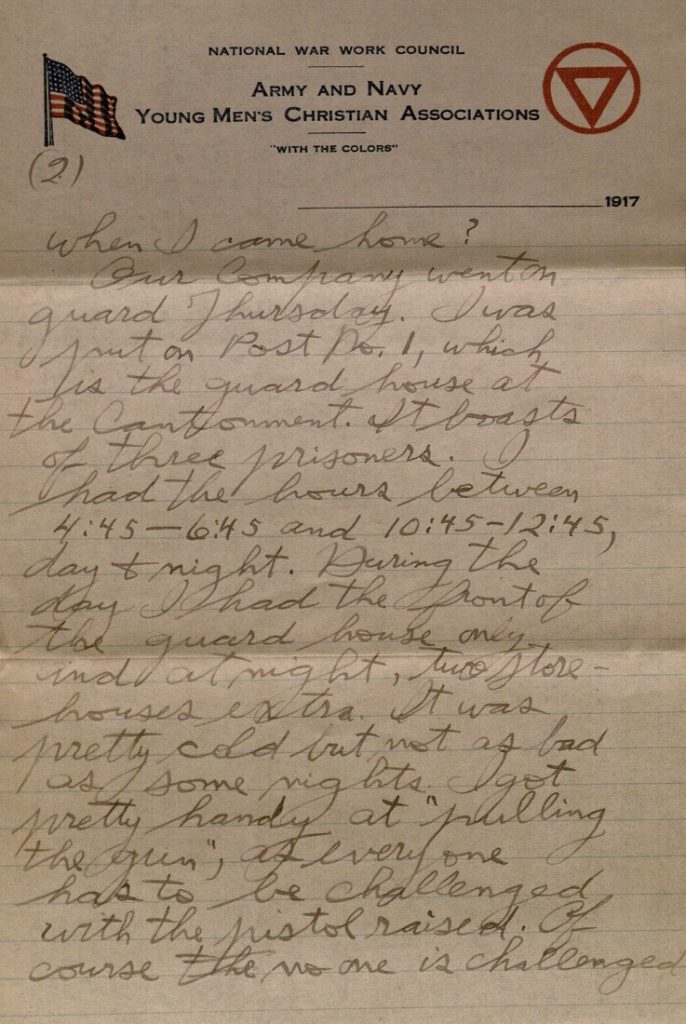

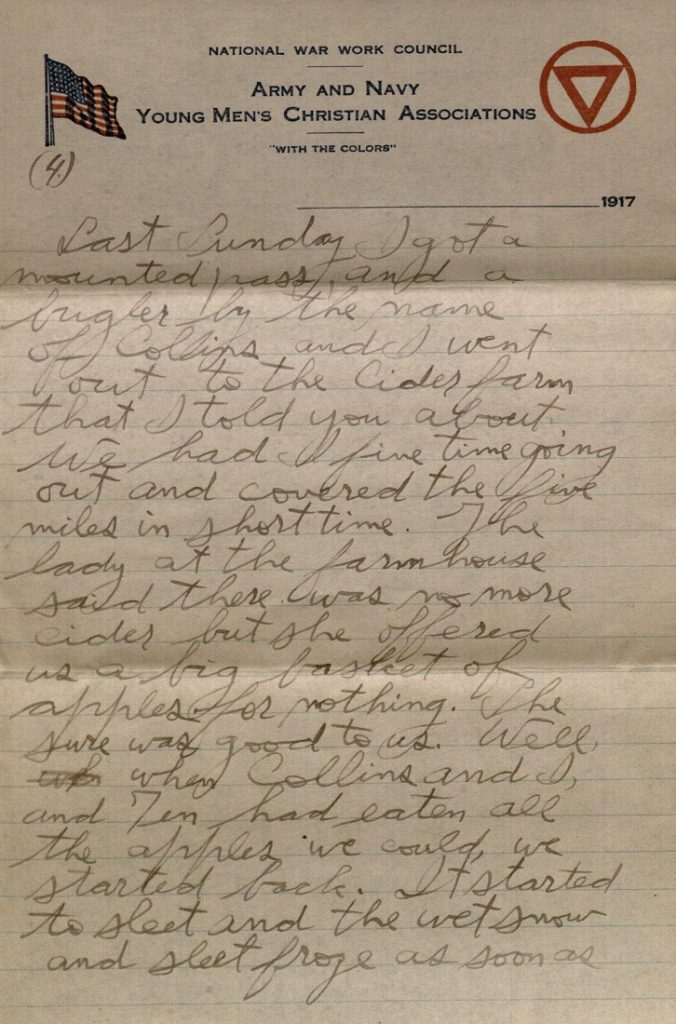

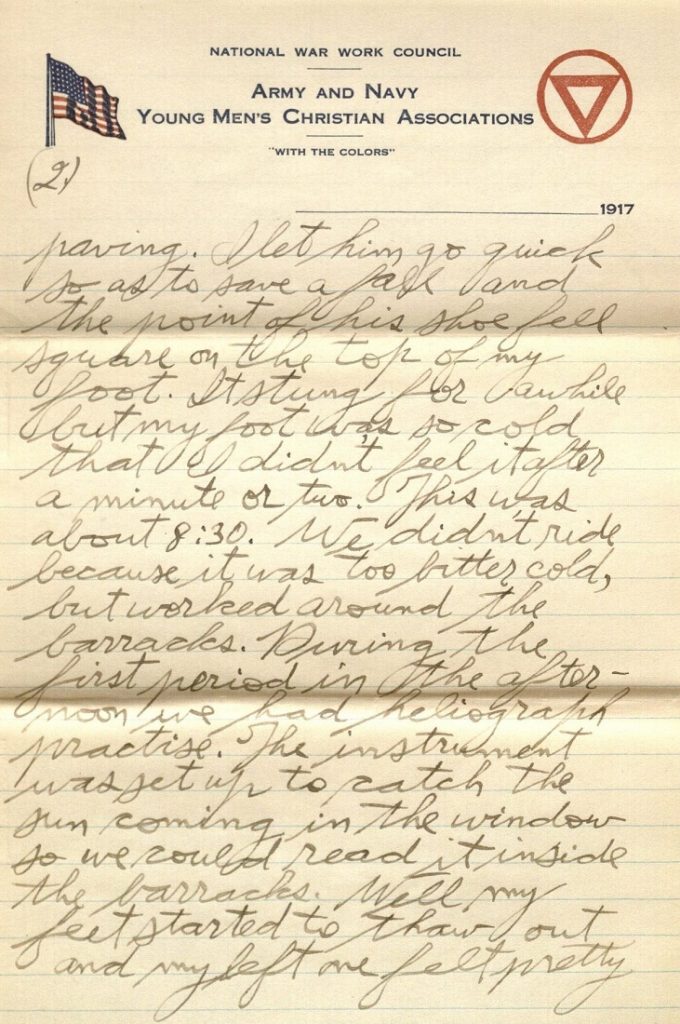

Tuesday afternoon we took the horses out for exercise. Nearly three weeks of loafing around in the corral made them feel pretty funny. We had quite an exciting time rounding up our own horses. I got “Ten” out before the stampede but had a gay time “snagging” a mule to lead. “Ten” had fattened a little since I saw him last, and when I saddled him, had to let out the cincha (which is the strap around the belly) about two inches more than usual. I am showing the effects of Army starvation in the same way. The mule I caught was a new one but he performed alright except that he kept a good stiff pull on the rope most of the time. Neither the Captain nor the Lietenants were with us and when we got into the woods we kicked a few slats loose. We hooted and yelled like a bunch of kids on the last day of school. The horses and mules had the same spirit and about every two minutes one would get loose (accidently on purpose on the part of the rider) and we would have some more fun catching them. Ten sure is one wise horse and is “on” to everything going, whether it’s heading off loose mules or jumping up a slippery hill. Gee, but you can’t imagine what great fun it is to ride a good, easily guided horse. When I think of the good times we used to have canoeing, and in the water, and shooting, it makes me wish we could be together on horses. We have fine saddles and the Company looks great mounted, every man in same uniform and every one in line with his “lead” horse to the right of the horse he is riding. We rode again Thursday but we didn’t have much fun as it was too slippery to let the horses go faster than a walk.

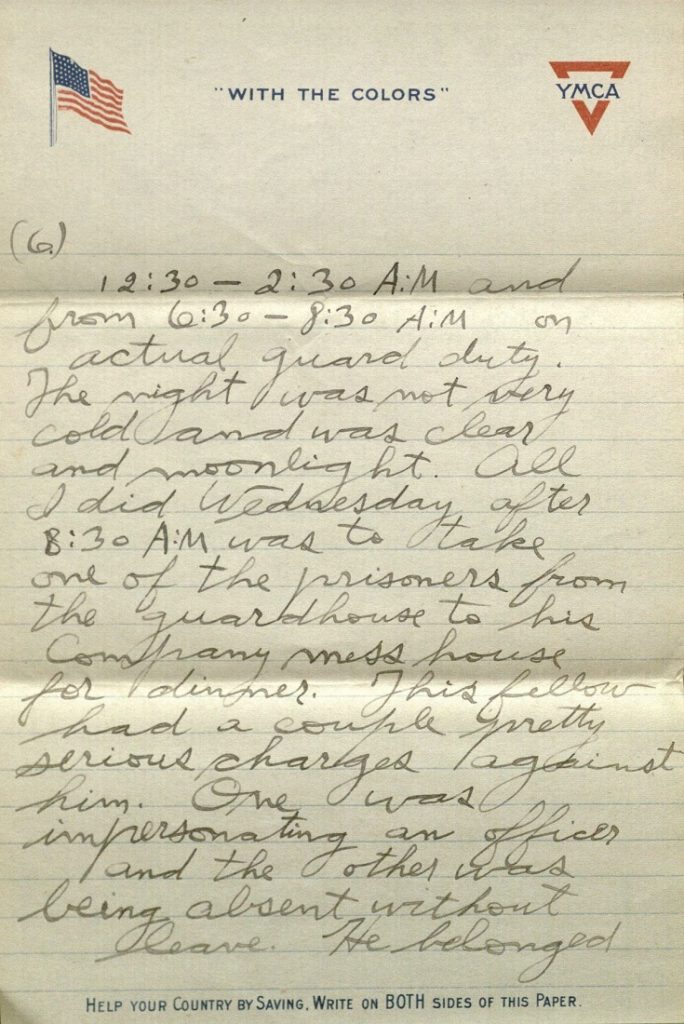

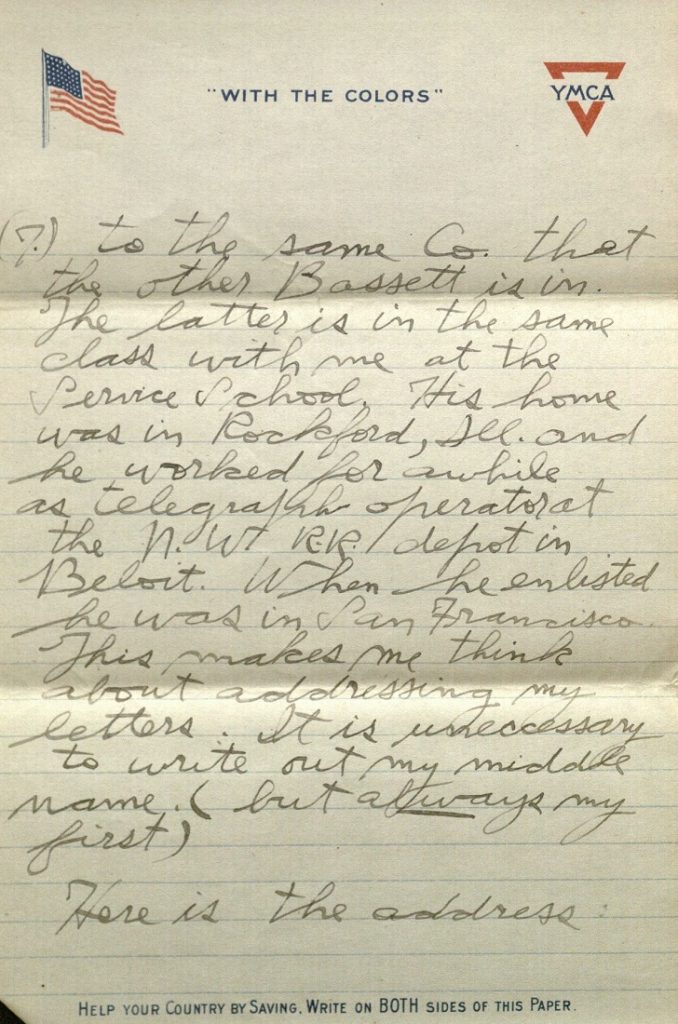

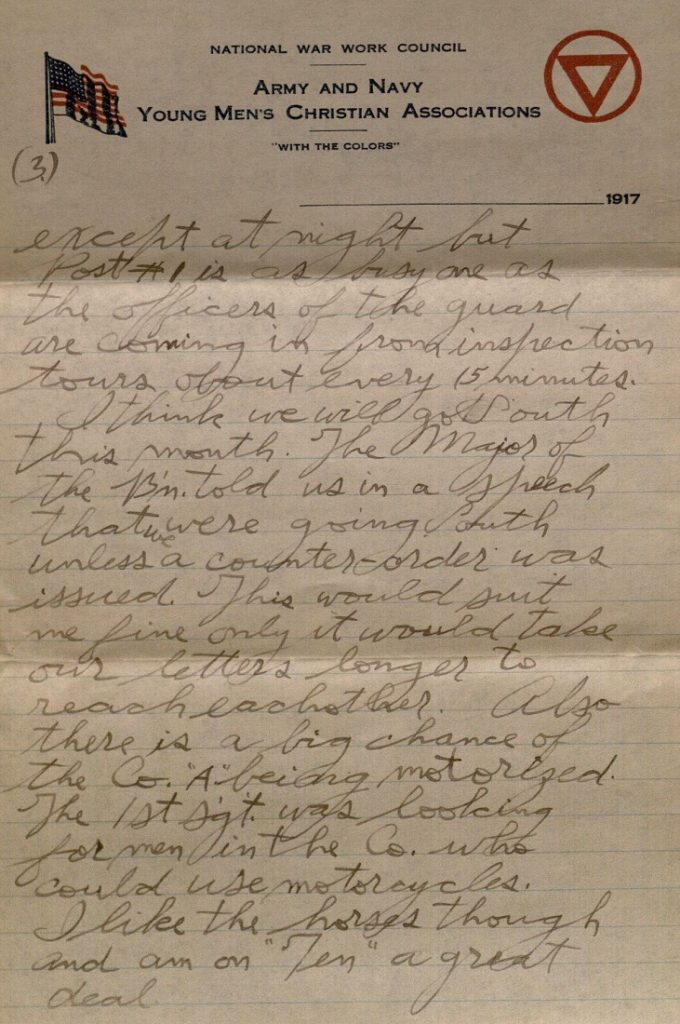

Tuesday night and Wednesday the Co. A-6 went on guard. I had it pretty soft, as I only had 6:30-8:30 P:M 12:30-2:30 A:M and from 6:30-8:30 A:M on actual guard duty. The night was not very cold and was clear and moonlight. All I did Wednesday after 8:30 A:M was to take one of the prisoners from the guardhouse to his Company mess house for dinner. This fellow had a couple pretty serious charges against him. One was impersonating an officer and the other was being absent without leave. He belonged to the same Co. that the other Bassett is in. The latter is in the same class with me at the Service School. His home was in Rockford, Ill. and he worked for awhile as telegraph operator at the N.W. R.R. depot in Beloit. When he enlisted he was in San Francisco. This makes me think about addressing my letters. It is uneccessary to write out my middle name. (but always my first)

Here is the address:

Forrest W. Bassett

Co. A-6th Fld. B’n. Signal Corps

Ft. Leavenworth, Kans.

Write Signal Corps in full as you have been doing but abbreviate the Fld. B’n.

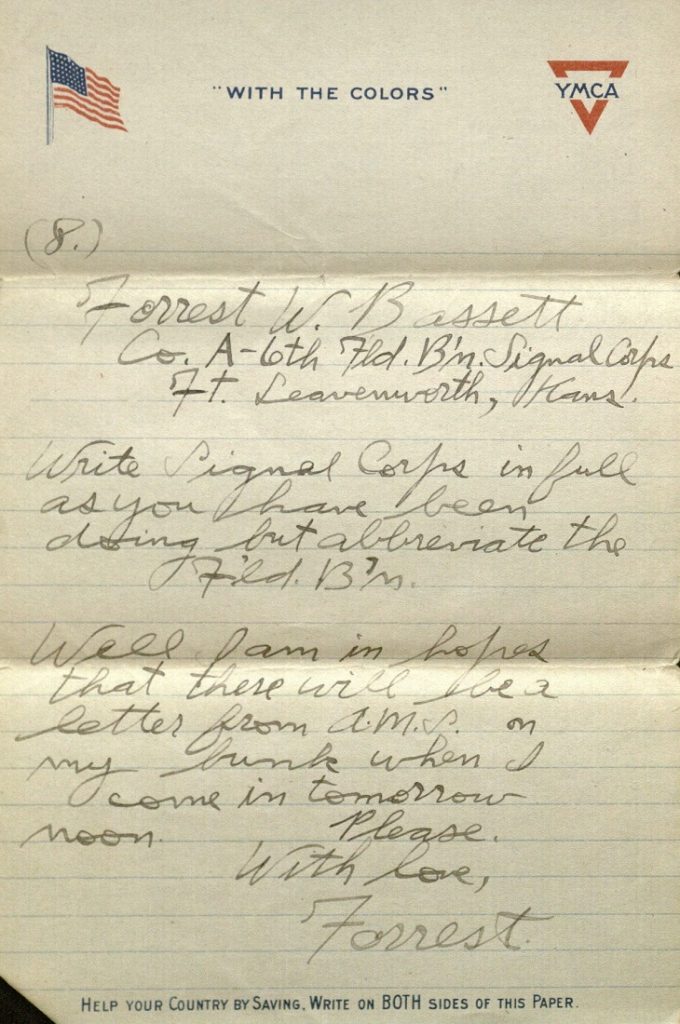

Well I am in hopes that there will be a letter from A.M.S. [Ava Marie Shaw] on my bunk when I come in tomorrow noon. Please.

With love,

Forrest.

Click image to enlarge.

Meredith Huff

Public Services

Emma Piazza

Public Services Student Assistant