In Good Paste: Selected Paste Papers from Spencer Research Library’s Special Collections

August 5th, 2025In the course of my work as a conservator at KU Libraries, one of my favorite bookbinding features to spot “in the wild” is paste paper. A book covered in paste paper might come to the lab for treatment, or I might catch sight of one while working in the stacks, and I always take a moment to look at them closely and enjoy the variety of colors, patterns, and styles that paste papers come in. It was no easy task to narrow down Spencer’s abundant selection of paste papers to just a few volumes that will be on view in a temporary exhibit in the North Gallery through August and September.

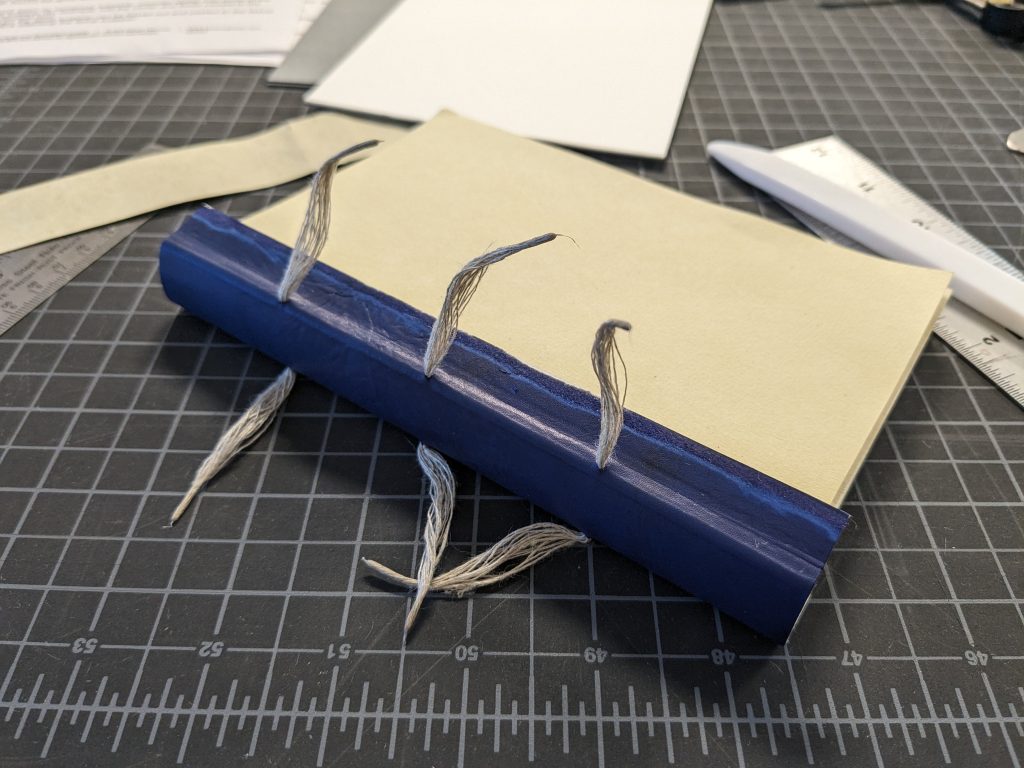

Paste paper is a style of decorative paper made by coating the surface of paper with a thick pigmented starch adhesive (usually wheat paste or methylcellulose) and then manipulating the wet paste mixture to create patterns. Combs, stamps, brushes, wadded paper or textiles, rollers, fingers and more could be used to create designs. Paste papers were an economical alternative to marbled papers, which required a high degree of skill and costly materials to produce. No special training or supplies were needed to make paste papers; bookbinders could create them right in their workshops with materials already at hand.

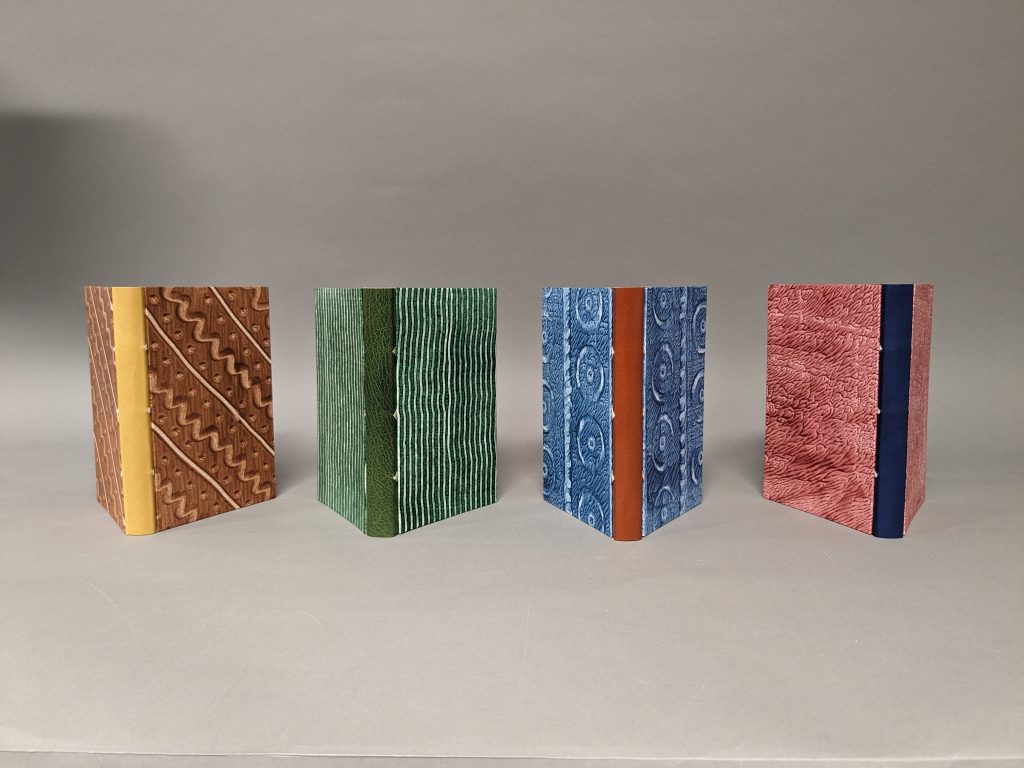

Paste papers were most often used for book covers and endpapers and were popular from the late 16th through the 18th century. Paste papers are often seen on books from Germany and Northern Europe, although there are many lovely examples of block-printed paste papers from Italy. There was renewed interest in paste papers during the Arts & Crafts movement of the late 19th and early 20th century. Today, paste papers are still created by book artists and hobbyists, and can be seen on some fine-press editions. The examples on view represent just a fraction of the many beautiful paste papers found in Spencer’s collections and available to view in the Reading Room.

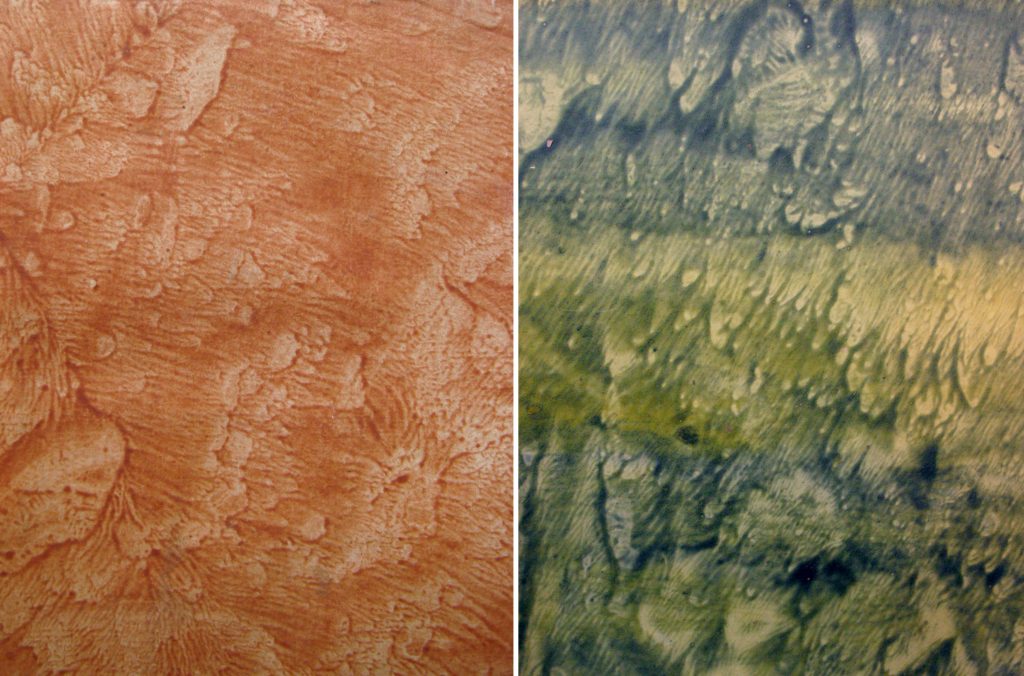

Pulled (or veined) paste papers were created by coating two sheets of paper with the colored paste, pressing the two pasted sides together, and then pulling the sheets apart, creating a unique wave-like pattern on each sheet.

Drawn paste papers (also called scraped or combed) were made by “fingerpainting” in the wet paste or dragging various implements through the paste layer. The results can range from painterly and whimsical to clean and graphic. A faux wood graining tool was used to create the pattern on Summerfield E156 (second from left).

These are two very different examples of daubed paste papers: a boldly colored design executed in a thick layer of paste, and a subtle pattern possibly created with stiff brush bristles.

This charming stamped (or printed) design appears, appropriately, on the cover of a book about decorative papers used in bookbinding. An assortment of stamps in architectural shapes were pressed into the paste to create the pattern. Spattered (or sprinkled) papers were made by loading a brush with the colored paste mixture and striking the brush while holding it above the paper, creating a shower of drops.

Block printed paste papers used a matrix, probably carved as for a woodblock print, that was “inked” with the colored paste and stamped onto the paper. These designs can be simple or ornate and often use multiple colors. On Summerfield C1300 (at left) the binder used block printed papers in two different patterns.

In these examples the makers have used a combination of techniques on a single sheet: stamped over drawn, drawn over pulled, and so on. D2763 (at right) is also an example of a paste paper created using a colored sheet of paper, instead of white or light paper, as the starting point.

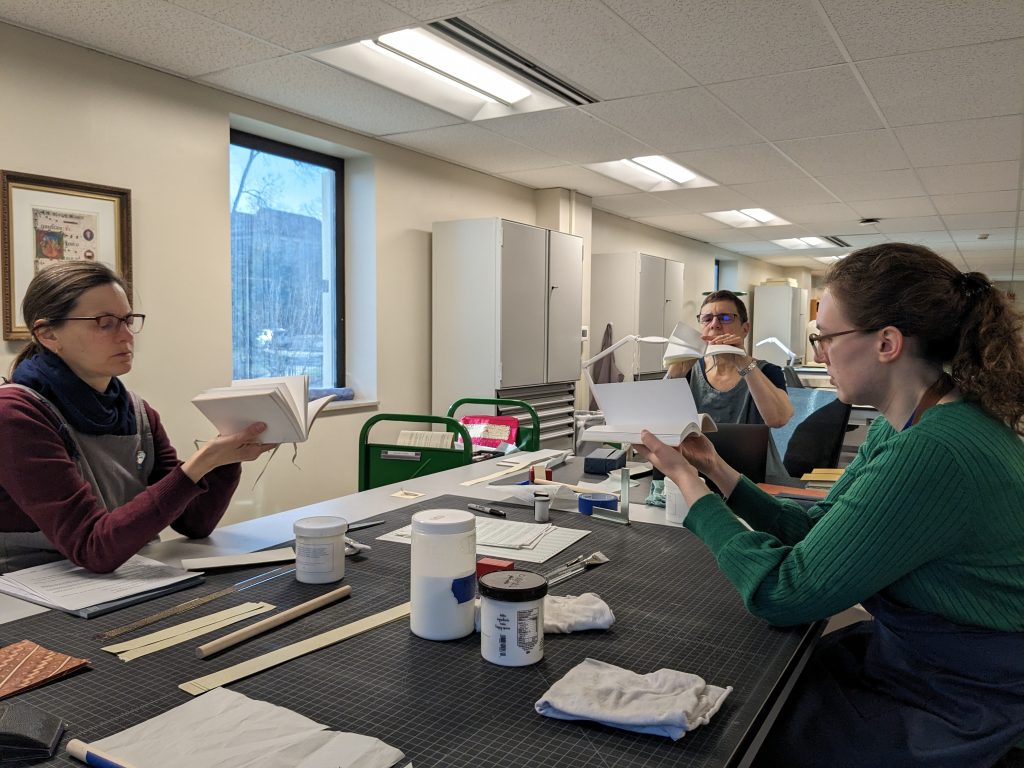

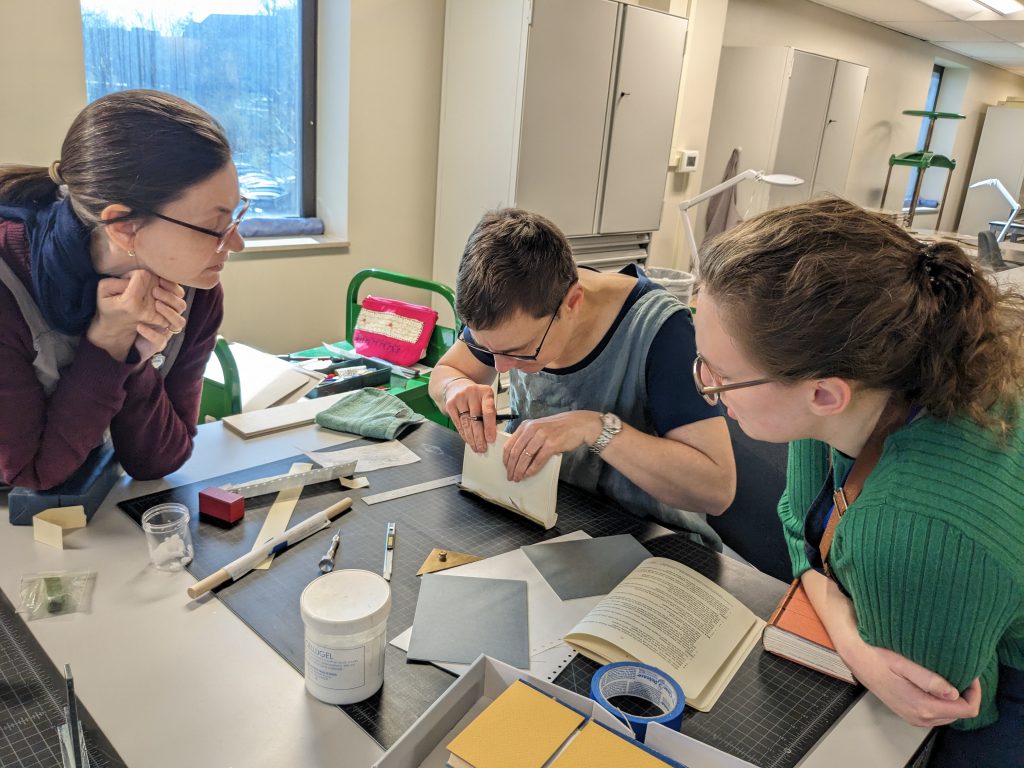

In Conservation Services we sometimes make paste papers to use in our own bookbinding models or in book making activities for colleagues or the public. Making paste papers is a fun and messy activity that invites exploration of colors, patterns, and mark-making tools. There are many online tutorials for making paste papers at home; bookbinder Erin Fletcher has a great video and written instructions on her blog. Tutorial // Paste Papers – Flash of the Hand

For more on paste papers, see Head of Conservation Services Whitney Baker’s 2012 blog post: Kenneth Spencer Research Library Blog » Historic Fingerpainting Seems More Dignified.

Angela Andres, special collections conservator