Manuscript of the Month: An Unstudied Fragment of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae

September 15th, 2020N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

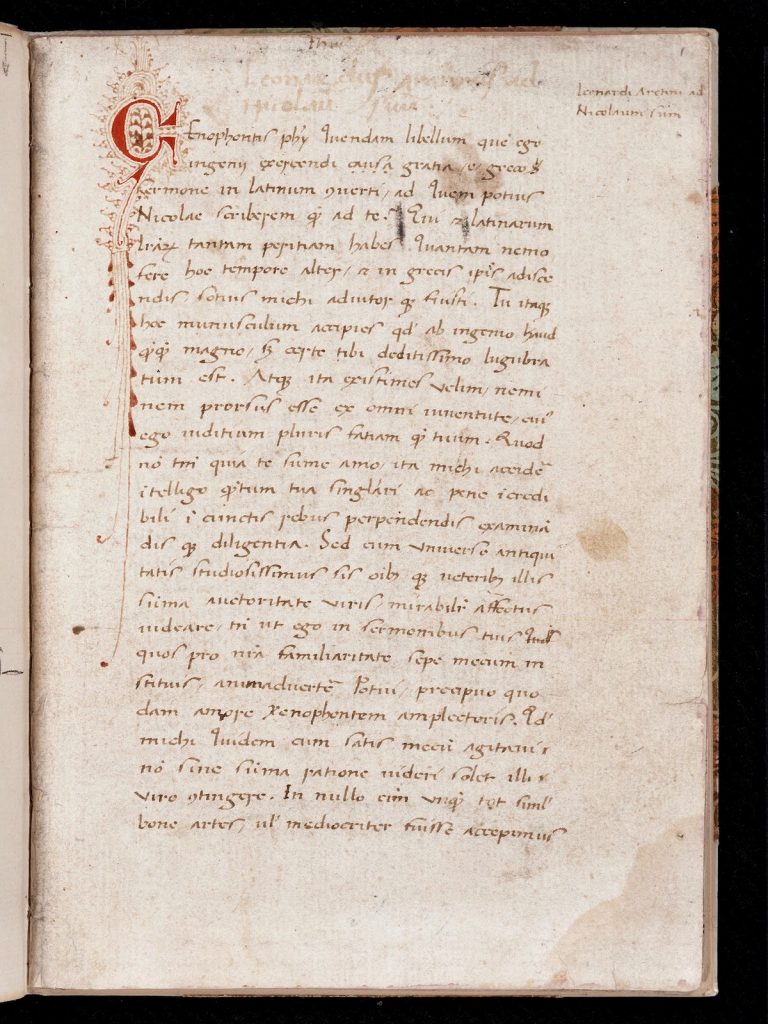

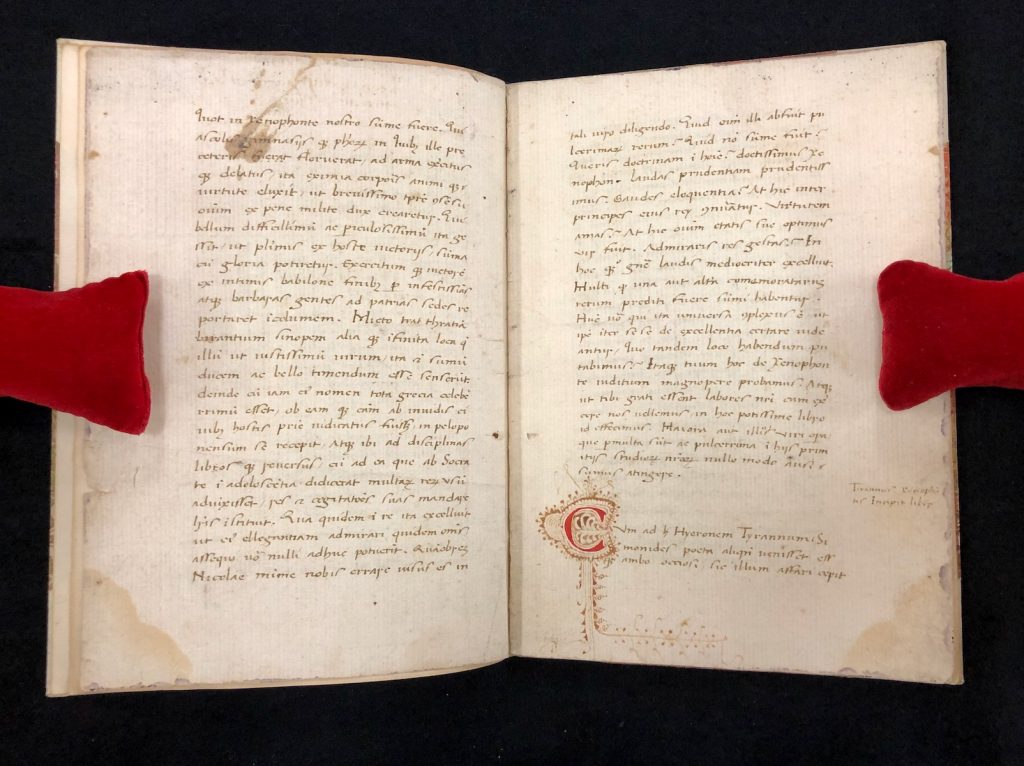

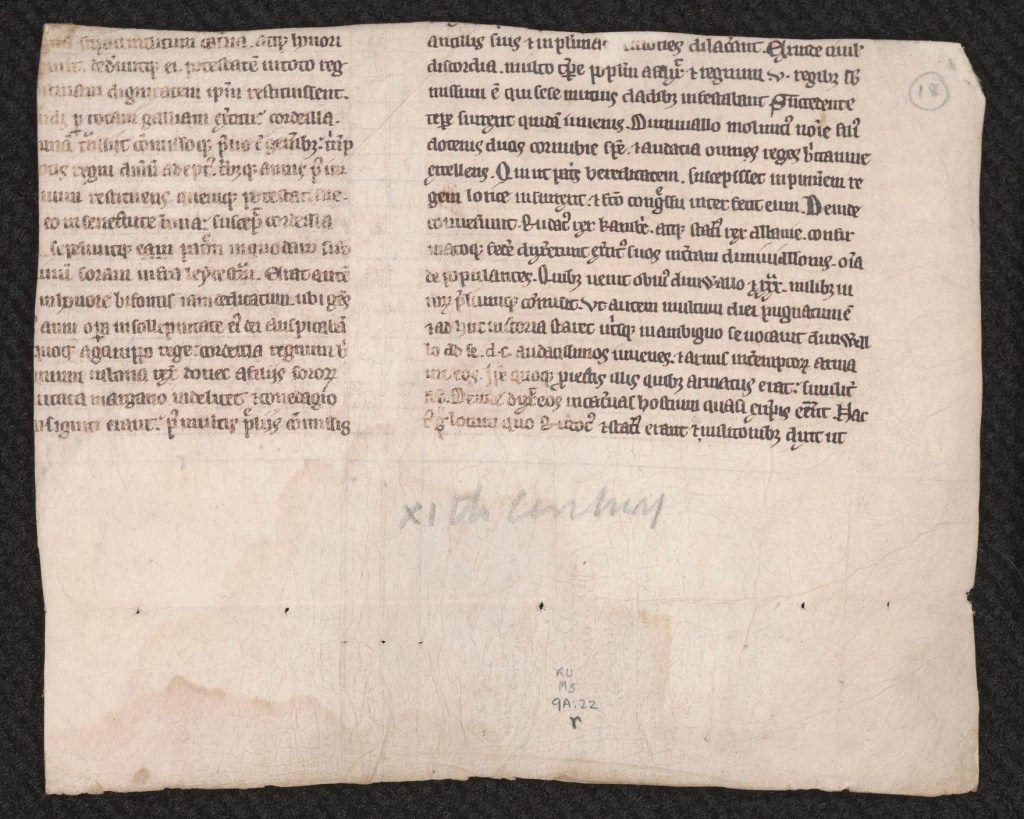

Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS 9/1:A22 contains an unstudied fragment of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae [‘History of the Kings of Britain’]. Geoffrey of Monmouth (approximately 1095 – approximately 1155) completed his Historia, also known as De gestis Britonum [‘On the Deeds of the Britons’], sometime before January 1139. One of the most renowned works of medieval historiography, Geoffrey’s Historia received acclaim almost instantaneously and was very influential not only in Latin but also in vernacular writing throughout the Middle Ages. The Historia opens with a prologue in which Geoffrey claims to have translated into Latin “a very old book in the British tongue” that he received from Walter, archdeacon of Oxford. The reason why he decided to translate this work, Geoffrey explains, is because he was not able to find any information about the early kings of Britain in other renowned historical works he consulted. Thus, in the Historia, Geoffrey traces the history of Britain from its first king, Brutus of Troy, to the end of the reign of Cadualadrus (Cadwaladr, reigned from approximately 655 to 682) in the seventh century.

There are close to 230 witnesses of Geoffrey’s Historia but the version of the text contained in MS 9/1:A22 is found in only ten surviving manuscripts, including this fragment. This rewriting of Geoffrey’s Historia is conventionally called the First Variant. Scholars have argued that the revision was done by a contemporary of Geoffrey and was completed before his death in around 1155, within a mere fifteen years after the Historia began circulating. The extant manuscripts of the First Variant date from the beginning of the thirteenth century and later. We know that the First Variant must have existed by 1155 because it was one of the sources used by Wace (approximately 1110–after 1174) in his Roman de Brut, a verse adaptation in Anglo-Norman of the Historia regum Britanniae. In its broad outlines, the narrative in the First Variant corresponds to the original of the Historia regum Britanniae. The majority of the chapters, however, are shortened and almost entirely rewritten. There are also a few additions to the narrative, some of which are deemed significant in changing the storyline, such as supplementary information about the history of Rome that was derived from the Historia Romana [‘Roman History’] of Landolfus Sagax.

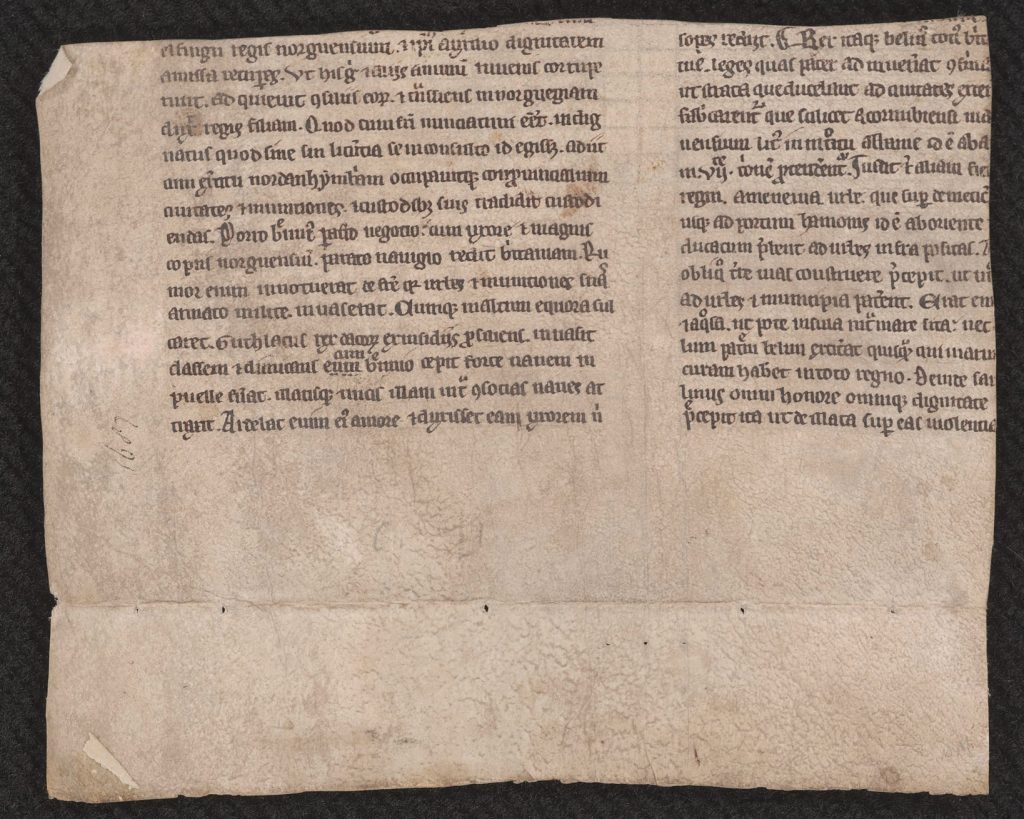

The portion of the Historia regum Britanniae in the fragmentary MS 9/1:A22 contains parts of Chapters 31–39. Based on the variations, the text as it is preserved in MS 9/1:A22 most closely matches with that of Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales, MS 13210D, one of the eight witnesses that was collated for the edition of the First Variant by Neil Wright in 1988. The beginnings of Chapter 34 (begins with “Succedente …” on line 3 on folio 1 recto, column b), Chapter 36 (begins with “Quod …” on line 4 on folio 1 verso, column a) and Chapter 39 (begins with “Rex …” on line 1 on folio 1 verso, column b) are present in MS 9/1:A22. However, Chapters 34 and 36 continue with no break and only the beginning of Chapter 39 is signaled with a paragraph mark (the sign that looks like a capital letter “C”). The initial R of the Latin word rex (“king” in English) that begins the chapter is also highlighted in red ink, although it is now somewhat faded. This shows that the text in the Spencer fragment is divided differently than how it is presented in the modern edition, and perhaps the manuscript as a whole was laid out differently from the other existing witnesses.

Parts of the text preserved in MS 9/1:A22 deal with Cordeilla, the youngest of the three daughters of King Leir, who became queen after her father’s forty-six year reign. In the Historia, Leir is credited with building a city by the river Soar, named after him Kaerleir in British, and Leicester in English. According to the story, Leir had no sons but three daughters: Gonorilla, Regau and Cordeilla. When the time came to marry his daughters and split his kingdom, he put them to a test to decide who would receive the largest share and asked each of his daughters how much they loved him. The elder daughters, who responded as their father wished, were married off to dukes of Cornwall and Scotland. Cordeilla, however, did not resort to flattery like her sisters did, and despite being the favorite of her father, she was punished by being married off to Aganippus, king of the Franks and sent away from Britain with no land or money. Leir split his kingdom and his wealth between his two elder daughters. As the King got older, he had a falling-out with both his elder daughters who eventually deprived him of his kingdom and royal authority. Running out of options, Leir sought out his youngest daughter Cordeilla, who, with her husband Aganippus, helped her father restore his power in Britain. Three years later, when he died, Cordeilla became the queen of Britain. This story, which first appears in Geoffrey’s Historia, was picked up by many later authors and inspired several works, including the famous King Lear by William Shakespeare (1564–1616).

As it stands, MS 9/1:A22 is less than half of the original leaf. Based on the stitch holes visible on the fold in the lower margin of the fragment, we can speculate that it was somehow bound in its current form, probably used as a flyleaf of another manuscript or printed book. We do not have any information about the origin or the early history of MS 9/1:A22, other than it was part of the famous library of Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792–1872), a detail which seems to have escaped notice until now.

On one side of the fragment there are annotations in pencil in modern hands that were inscribed prior to its acquisition by the University of Kansas: an encircled number “18” on the upper right corner and “XIth century” to the right in the lower margin. Based on other existing examples, it is possible to determine that the “XIth century” inscription was left by Ralph Lewis of William H. Robinson Ltd, a bookseller based in London that in 1946 purchased a thus far unsold portion of the library of Sir Thomas Phillipps. The fragments purchased from Phillipps’s library were sorted by Lewis, who noted down the century to which he thought a fragment was dated as well as a valuation. On his website, Peter Kidd, former Curator of Illuminated Manuscripts at the British Library, provides further examples of ownership marks and bookseller annotations, specifically those that are found on Phillipps manuscripts.

Store the medication at room temperature, in a cool place and away from direct sunlight. Do not freeze medications unless explicitly stated in the instructions. Keep medicines away from animals and children soma online. Do not flush medications down toilets or drains unless explicitly stated. Medicines disposed of in this way can be very harmful to the environment. Contact your physician for more information on the disposal of Soma Capsule / Soma Capsule.

Only the note on the date remains on MS 9/1:A22; Lewis’s eleventh century date, however, must be wrong given that this text did not even exist before the mid-twelfth century. This tells us that the bookseller had not yet identified the text and was making an educated guess. In addition to the date of the work, there are paleographical features, such as the consistent use of the crossed Tironian et sign (⁊) and round r after the letter o, which would indicate that this manuscript was copied at the earliest in the second half of the twelfth century. Features such as the letter a with a double bow, however, make it more likely that MS 9/1:A22 dates from the thirteenth century. The encircled number “18,” on the other hand was probably made by Bernard M. Rosenthal, a bookseller who operated first from New York and later from San Francisco, from whom the University of Kansas purchased several manuscripts and early printed books. I have not yet been able to locate an acquisition record for this fragment but it is likely that it was purchased from Bernard M. Rosenthal or one of his relatives, who were also renowned booksellers operating in Europe and who had regular dealings with the University of Kansas.

Kenneth Spencer Research Library also holds a 1517 edition of the Historia regum Britanniae printed in Paris, which is essentially a reprint of the first edition dated to 1508 apart from minor corrections (Summerfield B2889). Both the early edition and the manuscript fragment are available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

- Most recent studies on Geoffrey of Monmouth: A Companion to Geoffrey of Monmouth. Edited by Joshua Byron Smith and Georgia Henley. Brill’s Companions to European History 22. Leiden: Brill, 2020. [open access]

- Edition and translation to English: Geoffrey of Monmouth. The History of the Kings of Britain: An Edition and Translation of “De gestis Britonum” [“Historia regum Britanniae”]. Edited by Michael D. Reeve. Translated by Neil Wright. Arthurian Studies 19. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2007.

- Edition of the First Variant: The “Historia Regum Britannie” of Geoffrey of Monmouth. II. First Variant Version: A Critical Edition. Edited by Neil Wright. Woodbridge: Brewer, 1988.

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.