World War I Letters of Forrest W. Bassett: April 23-29, 1918

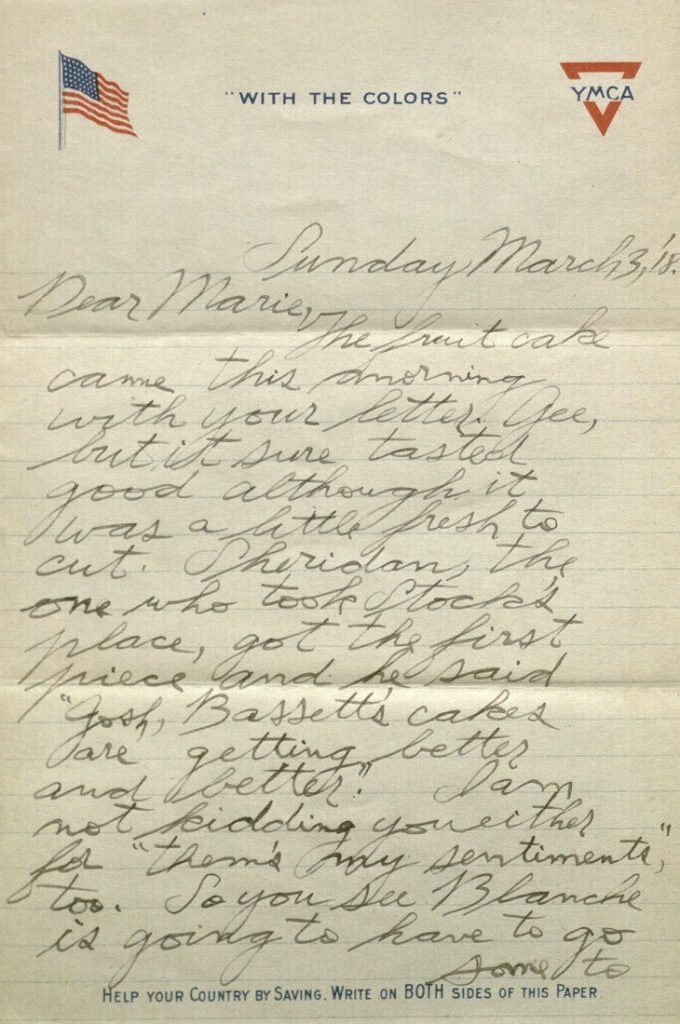

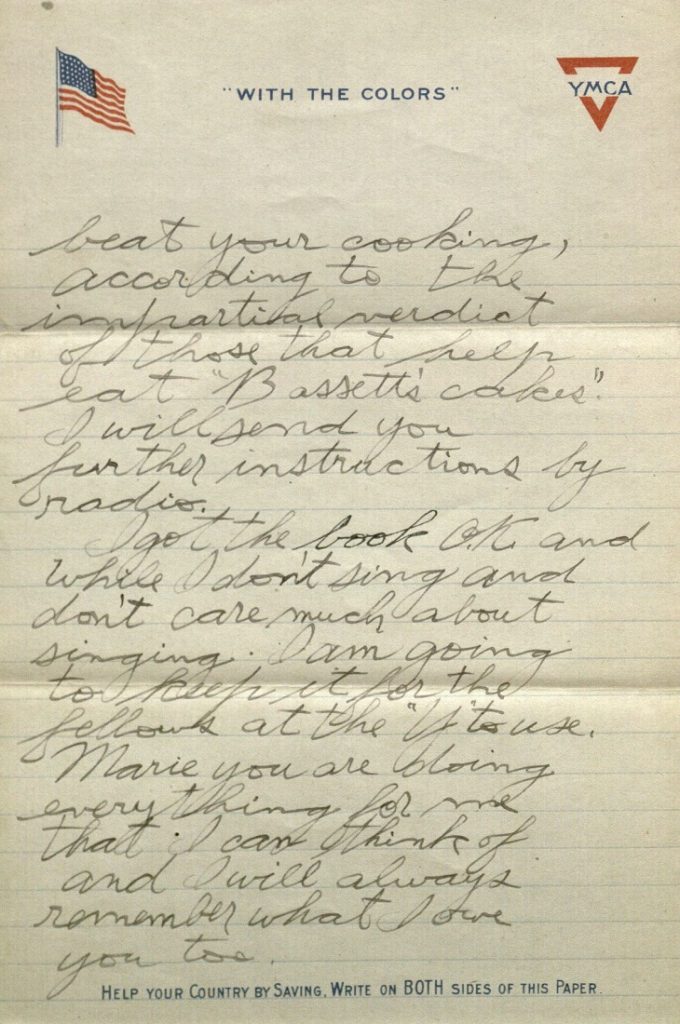

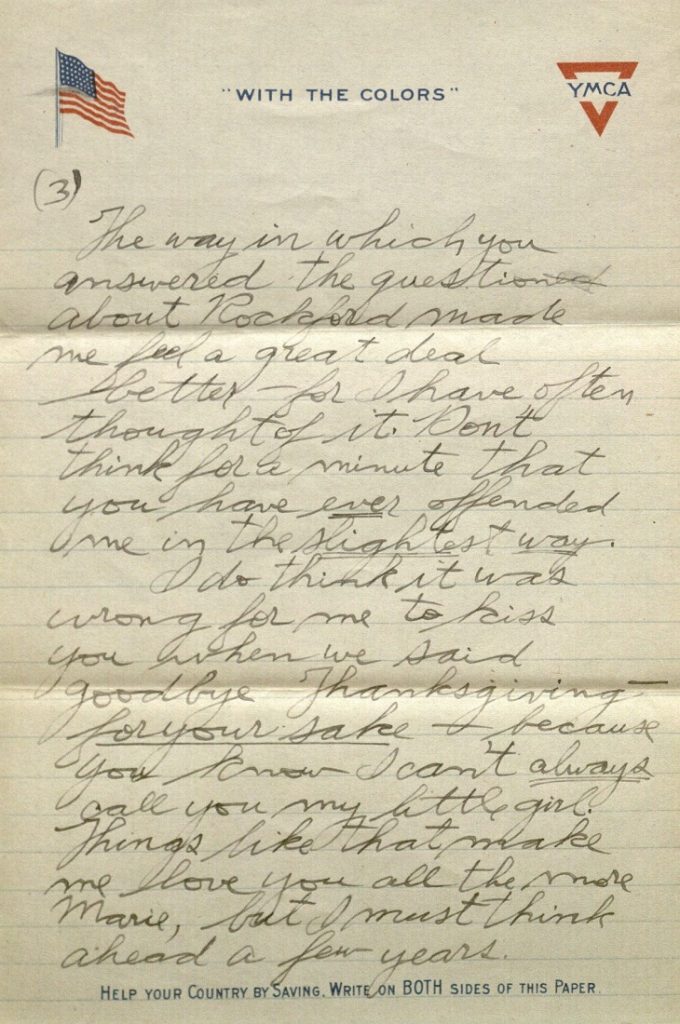

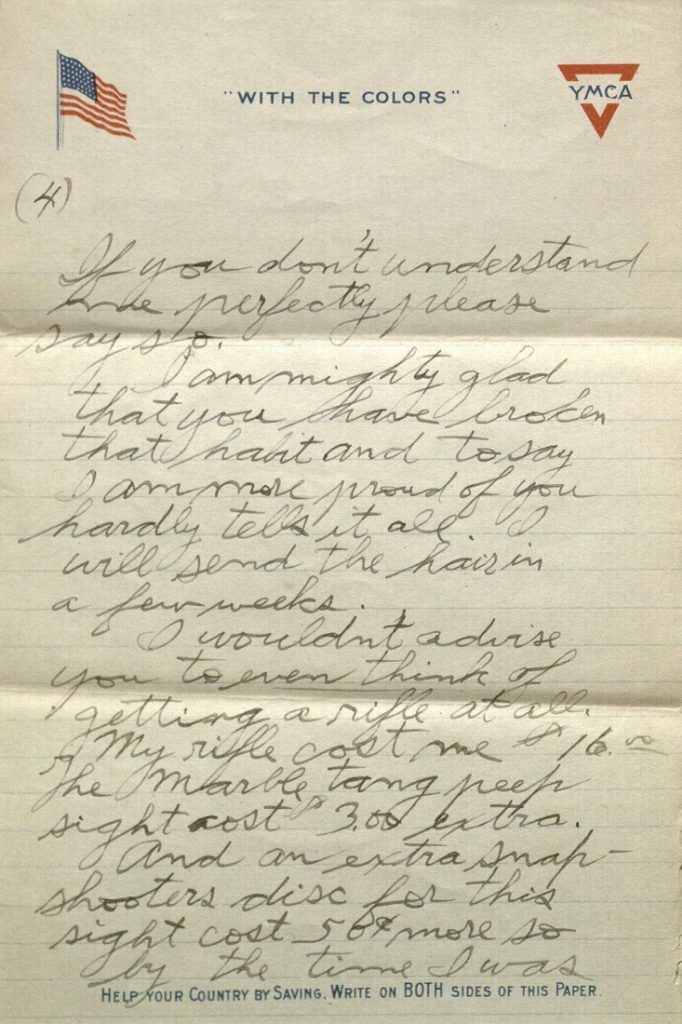

April 24th, 2018In honor of the centennial of World War I, we’re going to follow the experiences of one American soldier: nineteen-year-old Forrest W. Bassett, whose letters are held in Spencer’s Kansas Collection. Each Monday we’ll post a new entry, which will feature selected letters from Forrest to thirteen-year-old Ava Marie Shaw from that following week, one hundred years after he wrote them.

Forrest W. Bassett was born in Beloit, Wisconsin, on December 21, 1897 to Daniel F. and Ida V. Bassett. On July 20, 1917 he was sworn into military service at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri. Soon after, he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for training as a radio operator in Company A of the U. S. Signal Corps’ 6th Field Battalion.

Ava Marie Shaw was born in Chicago, Illinois, on October 12, 1903 to Robert and Esther Shaw. Both of Marie’s parents – and her three older siblings – were born in Wisconsin. By 1910 the family was living in Woodstock, Illinois, northwest of Chicago. By 1917 they were in Beloit.

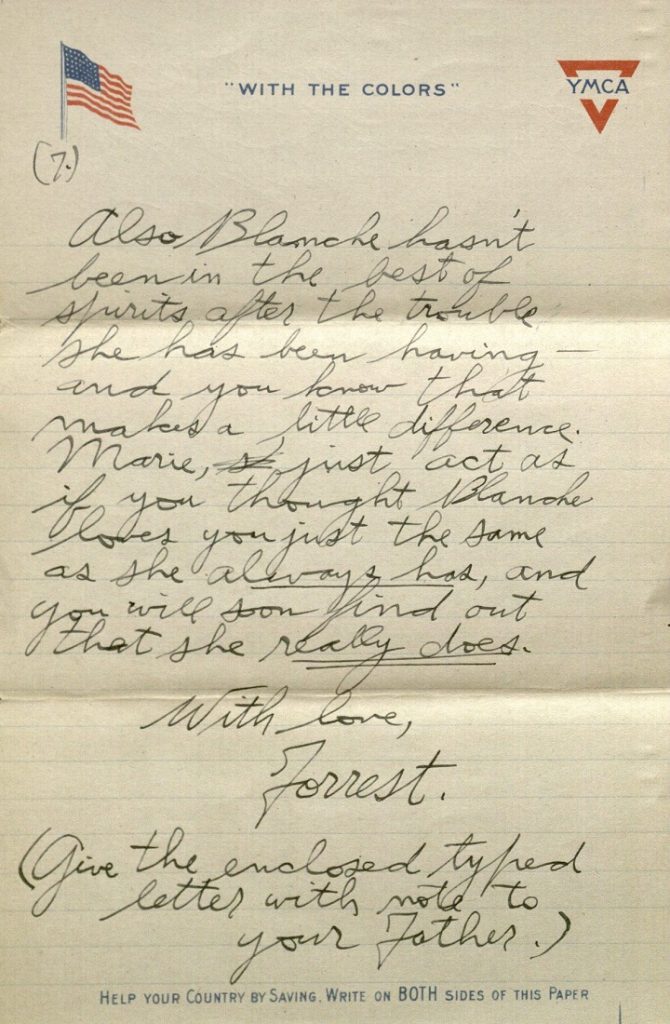

Frequently mentioned in the letters are Forrest’s older half-sister Blanche Treadway (born 1883), who had married Arthur Poquette in 1904, and Marie’s older sister Ethel (born 1896).

Highlights from this week’s letters include updates on Forrest’s transfer request (“I guess I may hope for a transfer, some day”) and advice to Marie about learning to telegraph (“to an experienced ear, there is as much beauty in good, accurate, clear cut ‘Morse’ as there is in a sheet of fancy writing”). “My life before I came here,” wrote Forrest on April 27, “seems more and more like a dream every day.”

Click images to enlarge.

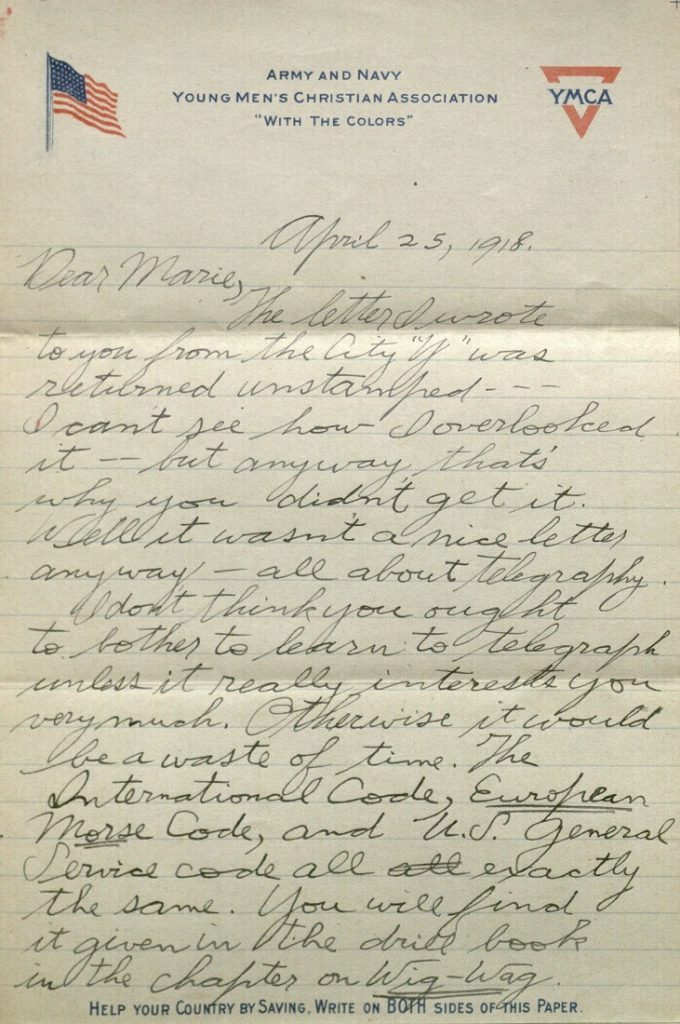

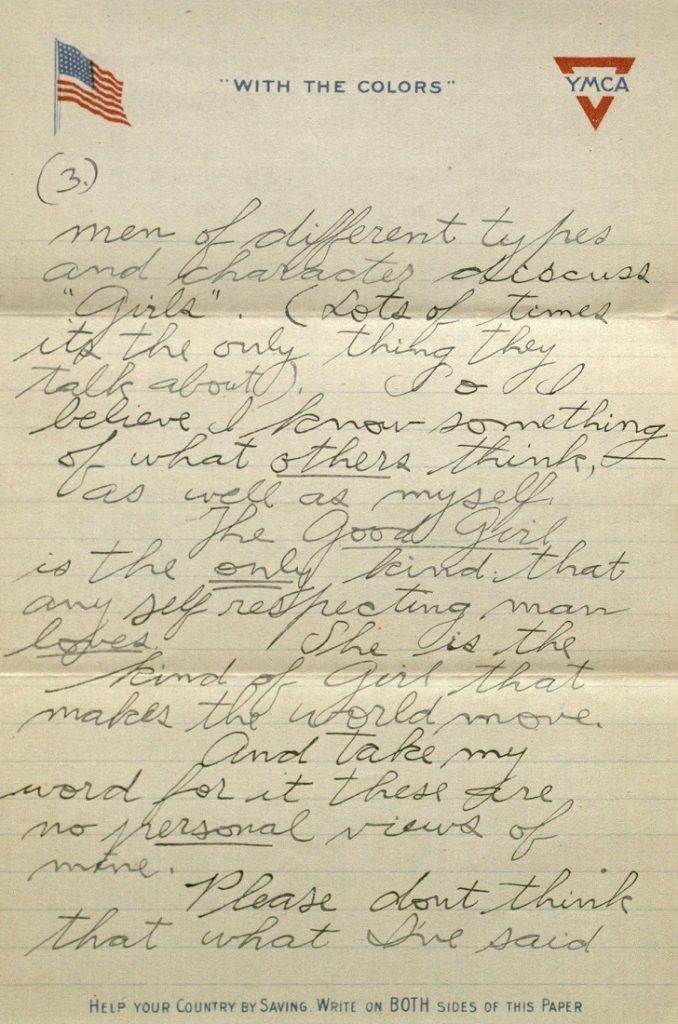

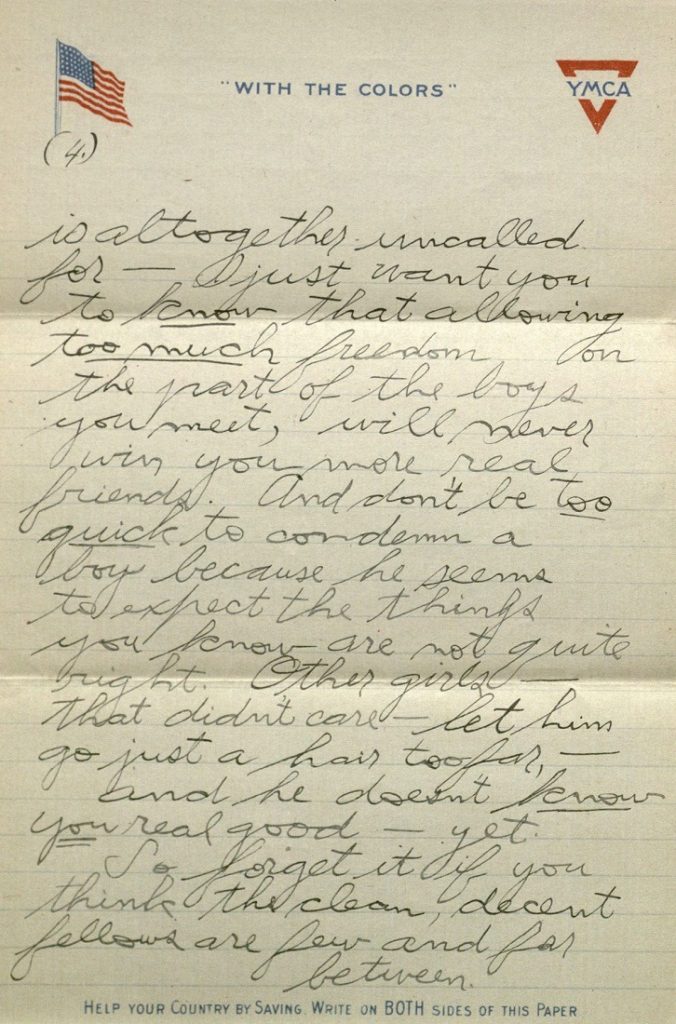

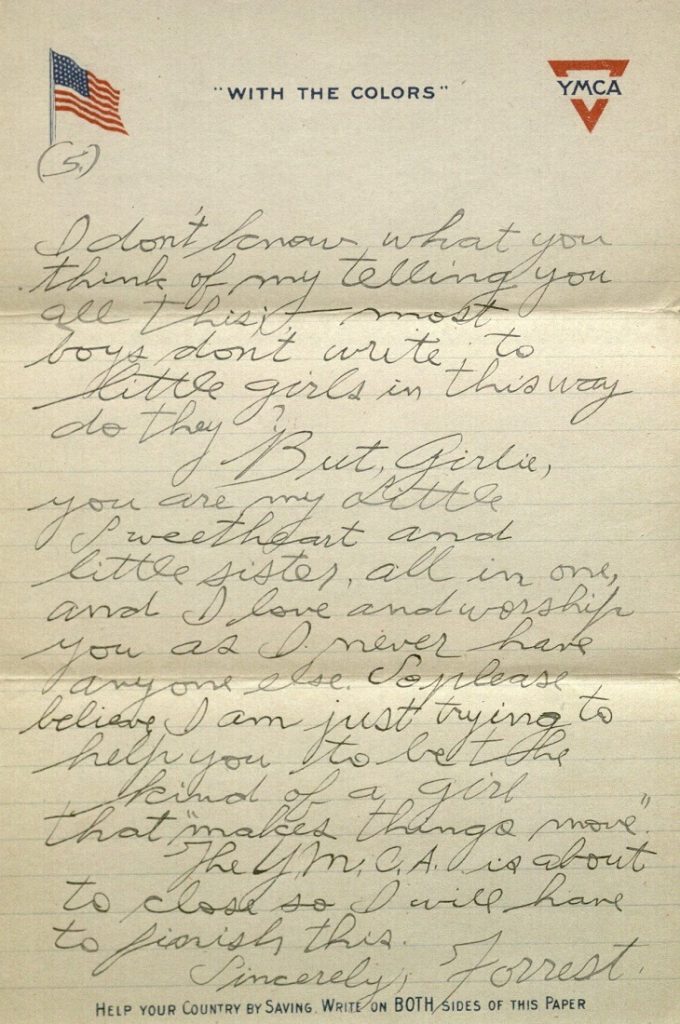

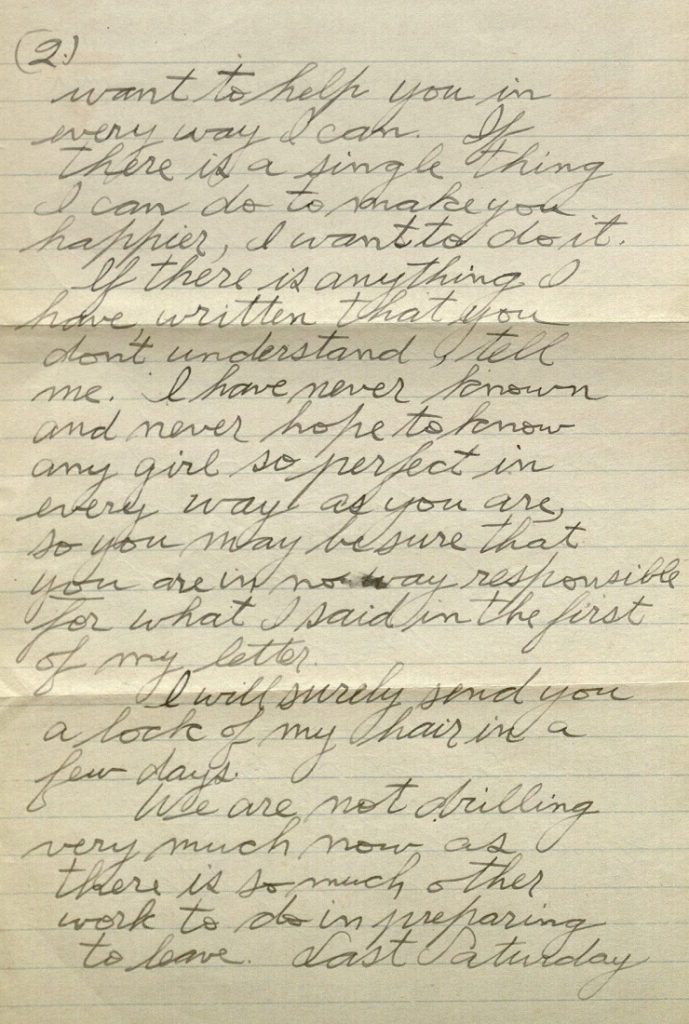

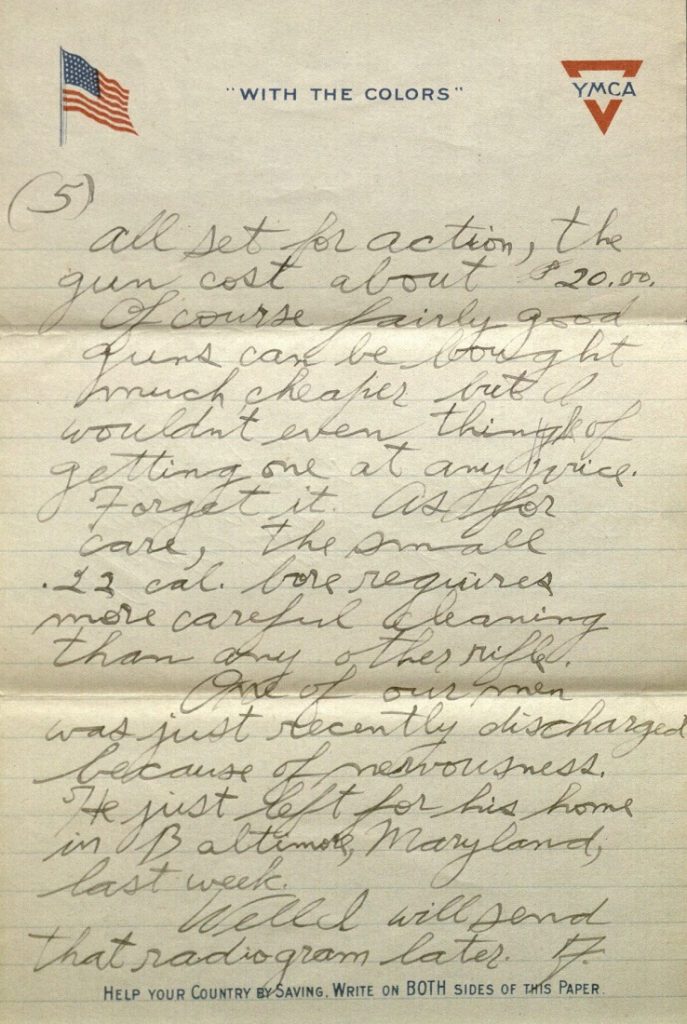

April 25, 1918.

Dear Marie,

The letter I wrote to you from the City “Y” was returned unstamped – I can’t see how I overlooked it – but anyway that’s why you didn’t get it. Well it wasn’t a nice letter anyway – all about telegraphy.

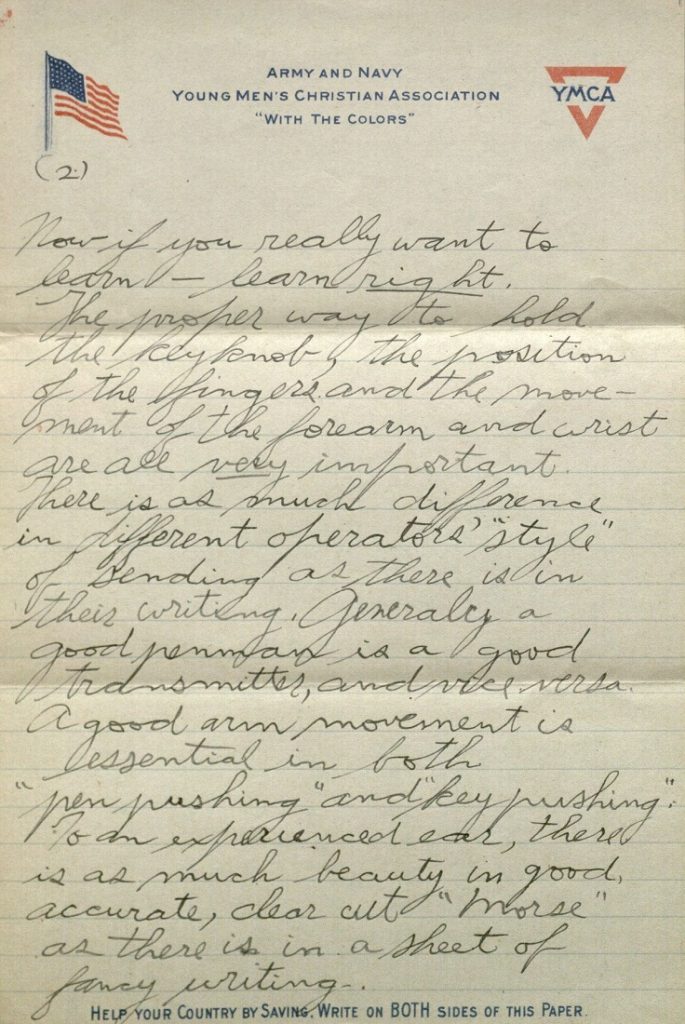

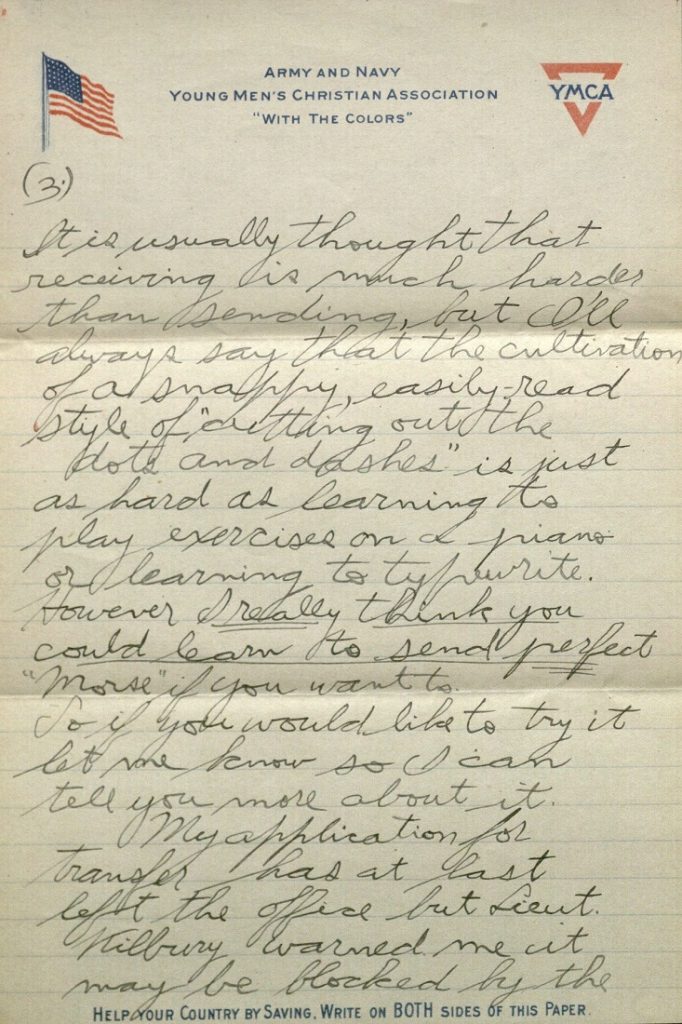

I don’t think you ought to bother to learn to telegraph unless it really interests you very much. Otherwise it would be a waste of time. The International Code, European Morse Code, and U.S. General Service code all exactly the same. You will find it given in the drill book in the chapter on Wig-Wag. Now if you really want to learn – learn right. The proper way to hold the key knob, the position of the fingers and the movement of the forearm and wrist are all very important. There is as much difference in different operators’ “style” of sending as there is in their writing. Generaly a good penman is a good transmitter, and vice versa. A good arm movement is essential in both “pen pushing” and “key pushing.” To an experienced ear, there is as much beauty in good, accurate, clear cut “Morse” as there is in a sheet of fancy writing. It is usually thought that receiving is much harder than sending, but I’ll always say that the cultivation of a snappy, easily-read style of “cutting out the dots and dashes” is just as hard as learning to play exercises on a piano or learning to typewrite. However I really think you could learn to send perfect “Morse” if you want to. So if you would like to try it let me know so I can tell you more about it.

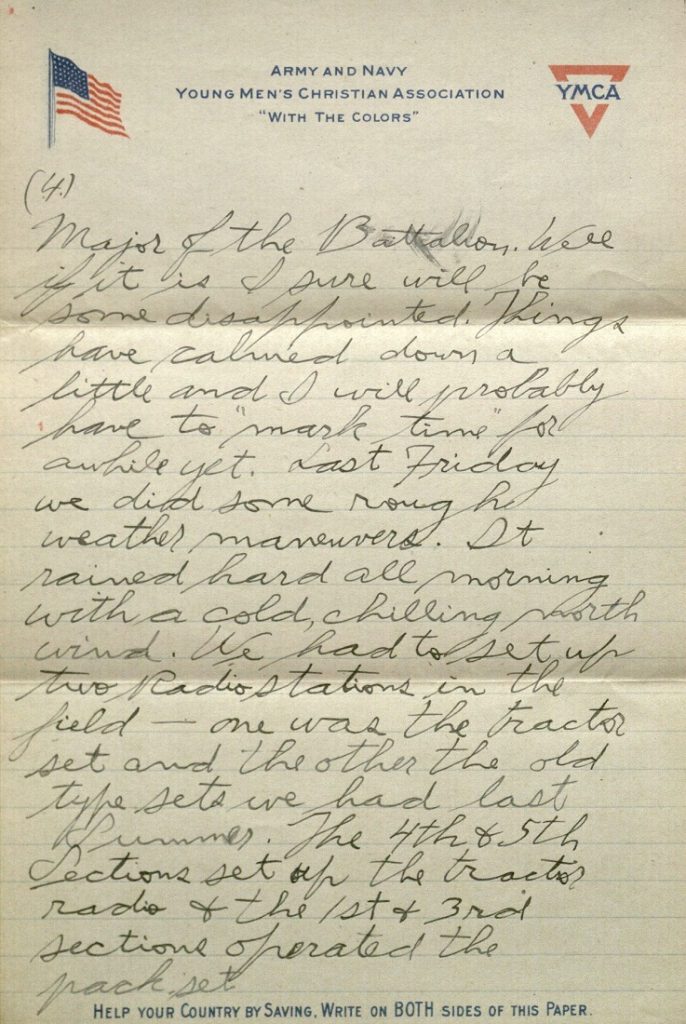

My application for transfer has at last left the office but Lieut. Kilbury warned me it may be blocked by the Major of the Battalion. Well if it is I sure will be some disappointed. Things have calmed down a little and I will probably have to “mark time” for awhile yet. Last Friday we did some rough weather maneuvers. It rained hard all morning with a cold, chilling north wind. We had to set up two Radio stations in the field – one was the tractor set and the other the old type sets we had last Summer. The 4th & 5th Sections set up the tractor radio & the 1st & 3rd sections operated the pack set.

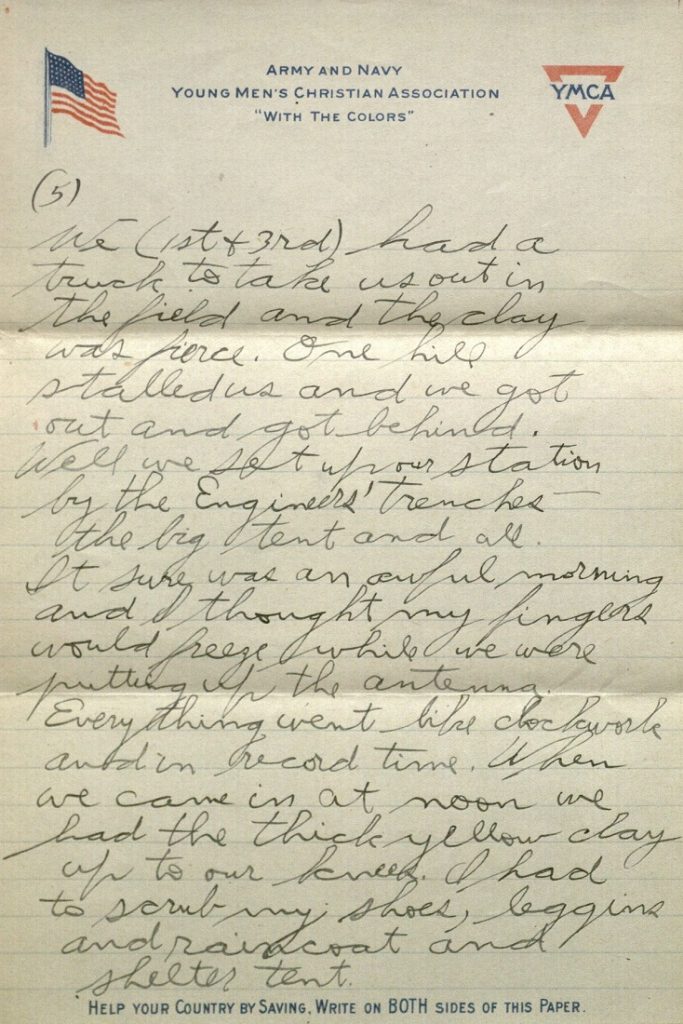

We (1st & 3rd) had a truck to take us out in the field and the clay was fierce. One hill stalled us and we got out and got behind. Well we set up our station by the Engineers’ trenches – the big tent and all. It sure was an awful morning and I thought my fingers would freeze while we were putting up the antenna. Everything went like clockwork and in record time. When we came in at noon we had the thick yellow clay up to our knees. I had to scrub my shoes, leggins and raincoat and shelter tent.

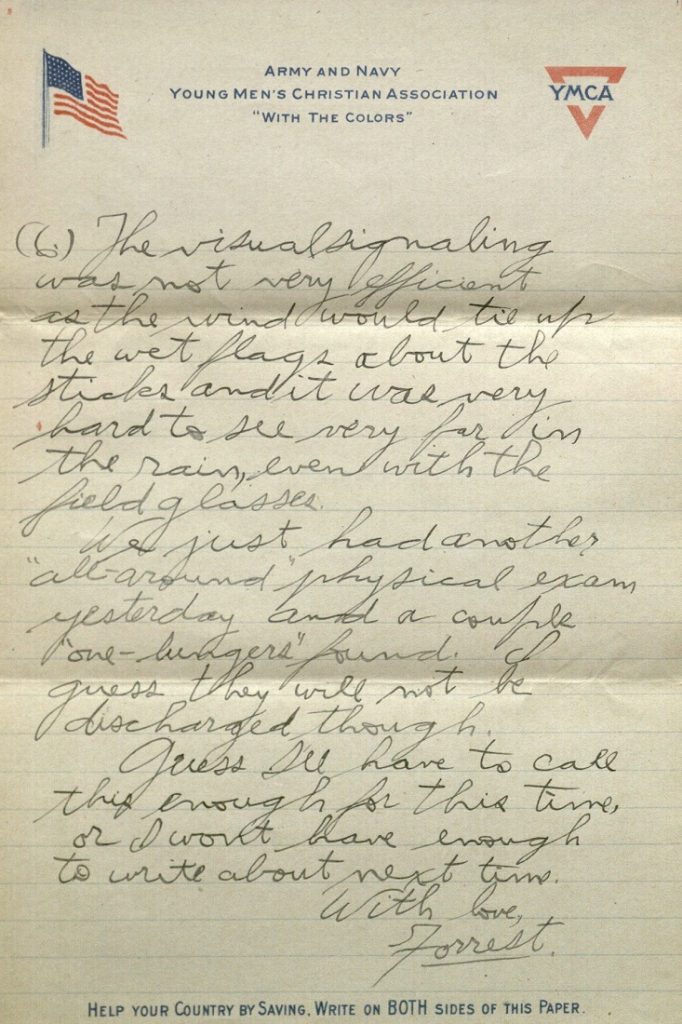

The visual signaling was not very efficient as the wind would tie up the wet flags about the sticks and it was very hard to see very far in the rain, even with the field glasses.

We just had another “all-around” physical exam yesterday and a couple “one-lungers” found. I guess they will not be discharged though.

Guess I’ll have to call this enough for this time, or I won’t have enough to write about next time.

With love,

Forrest.

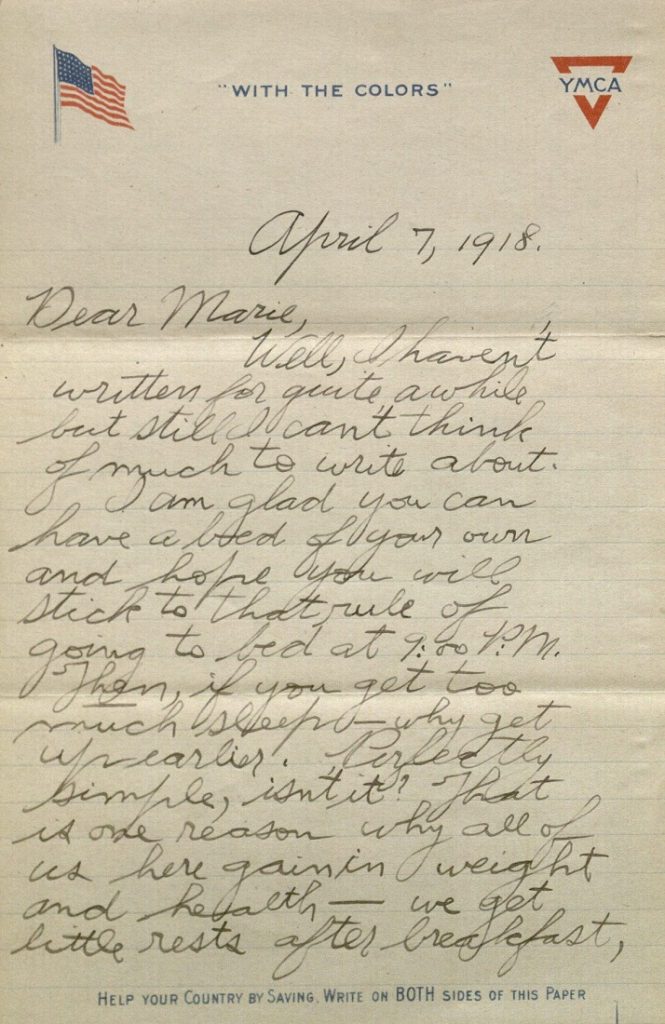

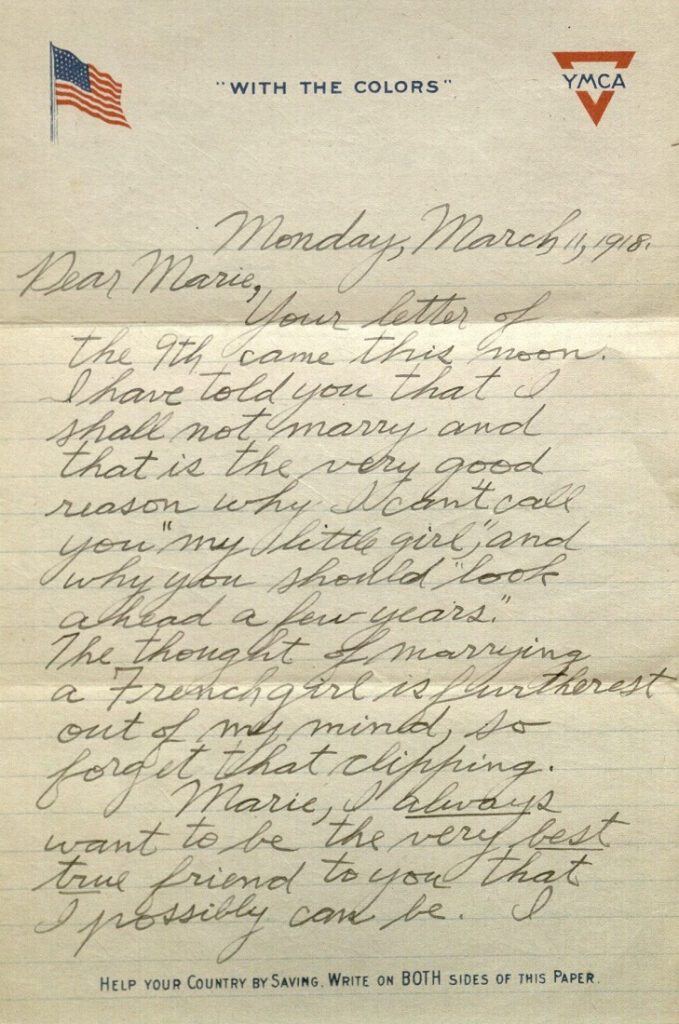

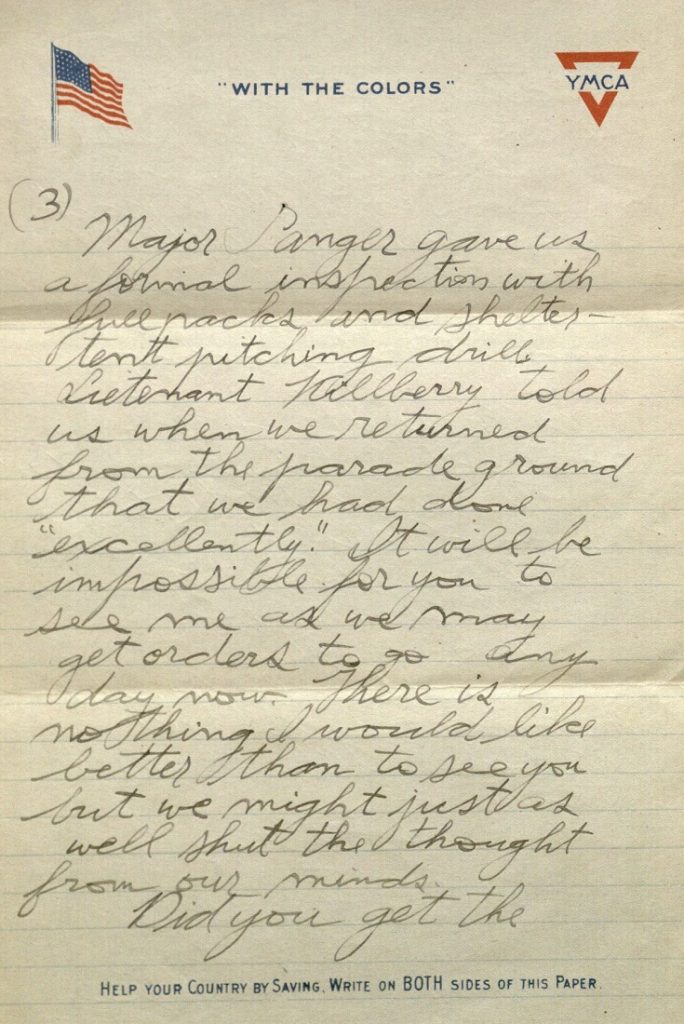

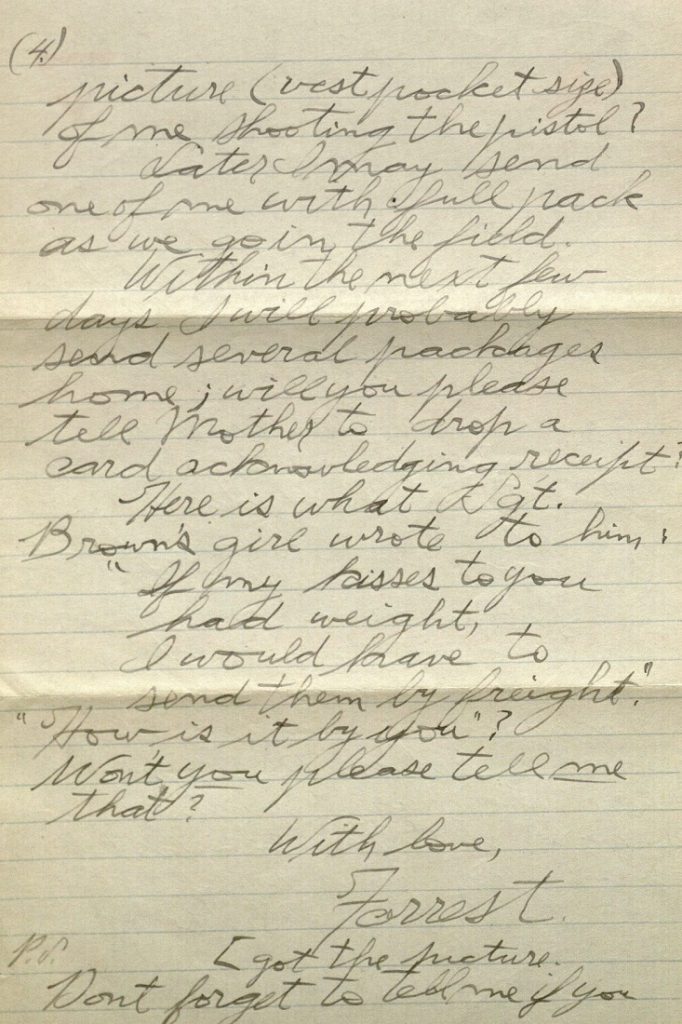

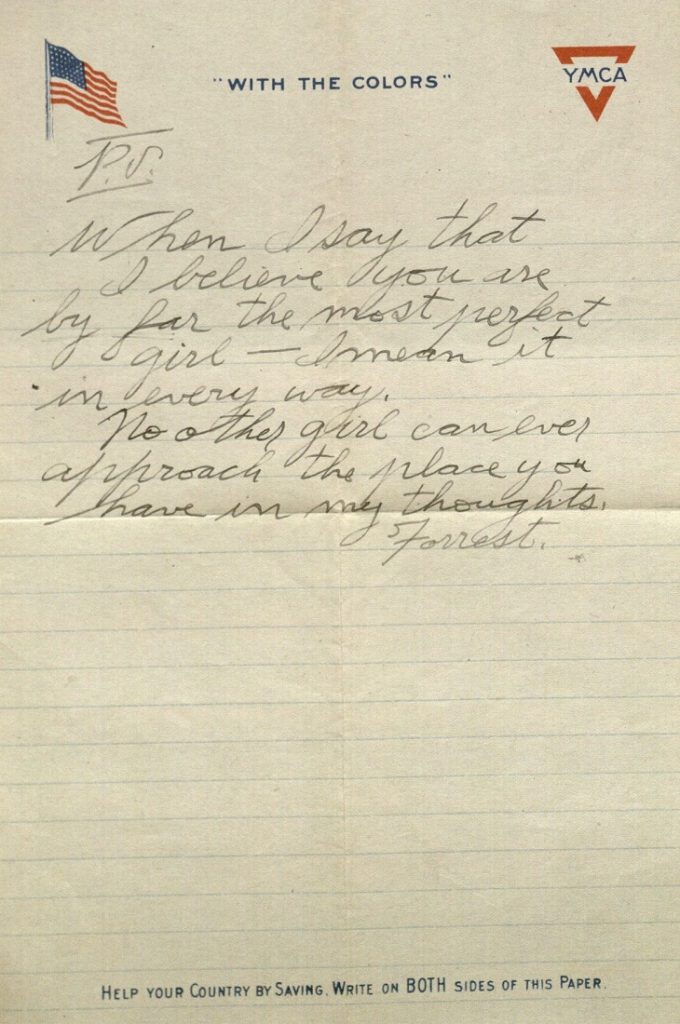

April 27, 1918.

Dear Marie,

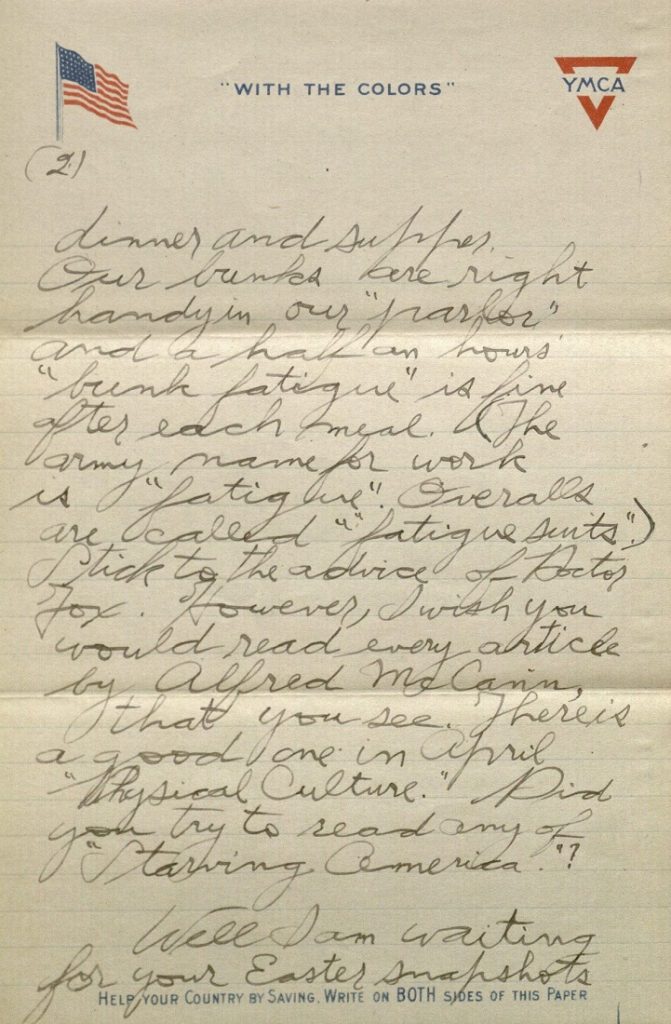

Your little note came this morning. I don’t blame you a bit for feeling that I ought to write oftener, for I guess I haven’t written much to anyone lately. Please don’t think that I haven’t thought of you much lately. And Marie, whatever you think don’t get the idea in your head that I might think myself too good for you or that I ever tire of your letters.

My life before I came here seems more and more like a dream every day. When I look at those two portraits of you (I have them back again) I can hardly believe that I ever held you close in my arms. It seems as if the days when we were together were years ago, and you seem like a big precious thing, altogether lost to me.

Well I don’t suppose I ought to write to you this way but I love you so much I can’t always hold back the feeling it causes.

Lietenant Kilbury is now a Captain and is our Company Commander. He has been in the Army all his life and has seen considerable active service. He is known all over the Fort as “Hard boiled Willie” and the title fits to a hair, for I don’t believe any officer could be any more rigid in discipline than he is. He sure is just plain “Hard Boiled.” He gave one man in our section five days in the guard house at hard labor for not marking his shoes with initials and Co. number. His favorite theme is absolute unyielding discipline – also that “non-commissioned officers will win the war.” Woe to the private that dares to speak to a non-com without addressing him as either “Corporal” or “Sergeant.”

He made a little speech this morning in which he said that Co-A of the 6th was the crack signal outfit in the Army and that he was going to make it a Company that never need have fear of meeting anything superior. Well there may be some “bunk” in that , but the Personnel Officer from Washington, who examined us for qualification as Signal men, told Captain Murphy that the men of “A”-Company were of the highest class he had worked with yet.

I guess my application for transfer passed the Major alright. Captain Kilbury marked my character “Excellent,” and the Company Clerk told me it was very unusual to get higher than “Very Good.” So I guess I may hope for a transfer, some day. Sergeant Baber, my Section Chief, has been recommended for the Officers traning Camp. Sergeant Williams, who used to be my Section Chief when I was in the 5th Section, went to the Officers training camp last January and is now a lieutenant. Well it’s a gay life and I can’t be worried, and lose my Milwaukee shape.

What kind of work do you intend to do this summer? I wish you would write more fully. I hate to think of you working outside, especially during a vacation.

With love,

Forrest.

Meredith Huff

Public Services

Emma Piazza

Public Services Student Assistant