Ho Chi Minh, the Black Panther Party, and the Struggle for Self-Determination

January 15th, 2020The temporary exhibit described in this post will be on display in Spencer’s North Gallery through the end of January.

As a student assistant for the African American Experience Collections, I recently had an opportunity to produce a temporary exhibit in Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

After reviewing the 1968-1970 issues of The Black Panther, which was published by the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California, I uncovered an astonishing connection linking African Americans and Asians: In 1969 and 1970, the Minister of Information of the Black Panther Party, Eldridge Cleaver, led delegations of African Americans to visit North Vietnam, North Korea, and China.

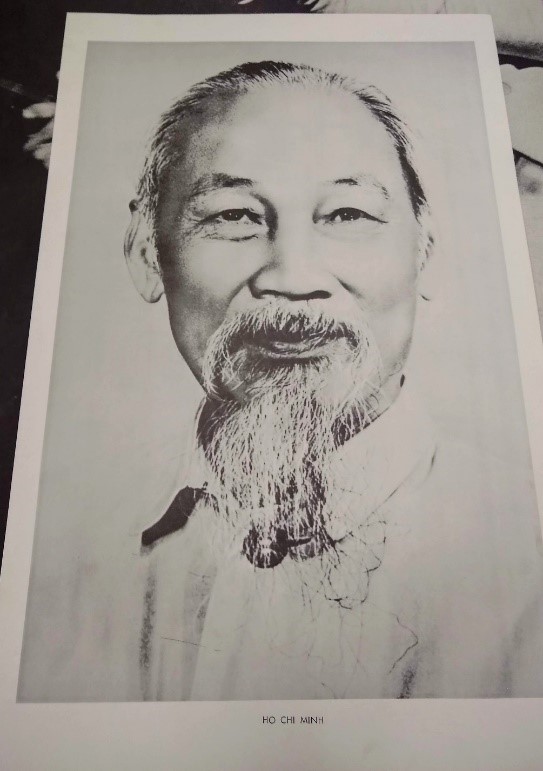

Although I would have loved exploring the connections between the Black Panther Party, North Korea, and China, as a Vietnamese-American, I found myself inextricably drawn to the history of Ho Chi Minh and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. With the topic of my temporary exhibit decided, I scoured Kenneth Spencer’s collections in search of material relating to Ho Chi Minh and the Black Panther Party.

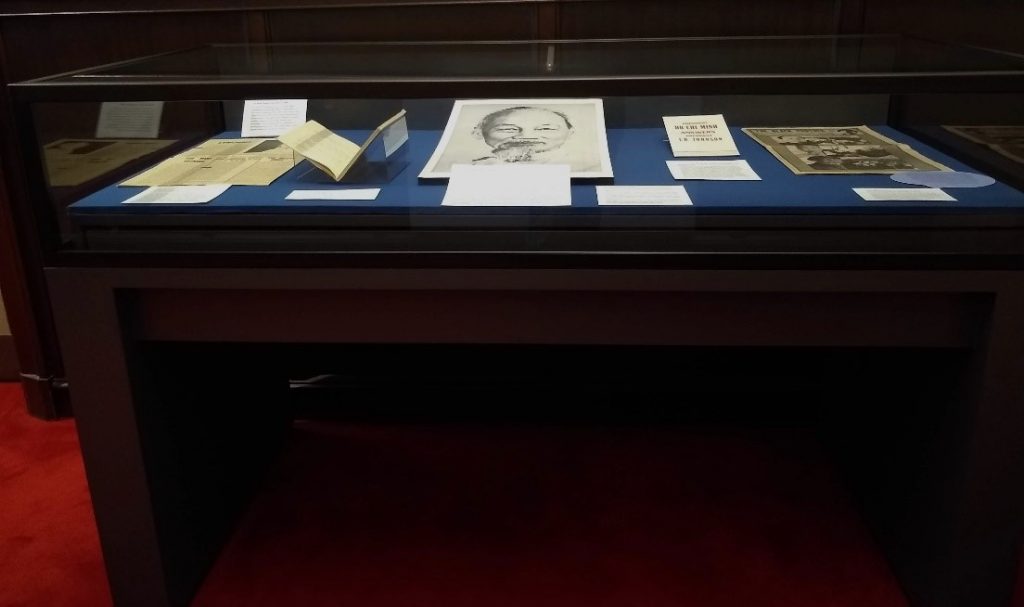

For my first exhibit case, I decided to focus solely upon Ho Chi Minh. (Notably, Ho Chi Minh is one of many pseudonyms he adopted.) I found two Black Panther Party newspapers in the African American Experience Collections but for the rest of my materials, I went digging around in the Wilcox Collection. I was fortunate enough to find a wonderful poster of Ho Chi Minh in the Counter Culture Posters Collection, along with two primary sources written by Ho, including Ho Chi Minh Answers President L.B. Johnson (Call Number: RH WL B3690) and Against U.S. Aggression for National Salvation (Call Number: RH WL B3593).

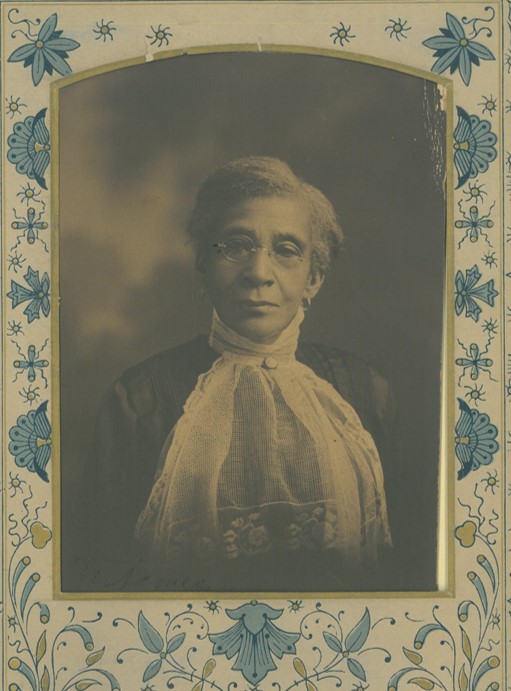

Around the same time I was creating my temporary exhibit, I was also participating in an independent study relating to eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twentieth-century Vietnamese history. There I learned that in 1924 Ho Chi Minh had penned two essays titled “Lynching” and “the Ku Klux Klan.” In these essays, Ho Chi Minh wrote about the violence and racism African Americans faced in the United States, demonstrating his awareness of the oppressions endured by peoples outside Vietnam. It is highly probable that Ho read documents published from the NAACP’s anti-lynching campaign, which included information and statistics about African Americans lynched in the United States each year beginning in 1909. However, it is also worth noting that Ho worked aboard a steamship and traveled internationally to the United States, France, England, and other European countries.

Some of the most memorable quotes from his essay on “Lynching” include:

- “After sixty-five years of so-called emancipation, American Negroes still endure atrocious moral and material sufferings, of which the most cruel and horrible is the custom of lynching.”

- “From 1899 to 1919, 2,600 Blacks were lynched, including 51 women and girls and ten former Great War soldiers.”

- “Among 78 Blacks lynched in 1919, 11 were burned alive, three burned after having been killed, 31 shot, three tortured to death, one cut into pieces, one drowned and 11 put to death by various means.”

- “Georgia heads the list with 22 victims. Mississippi follows with 12. Both have also three lynched soldiers to their credit.”

Upon Ho Chi Minh’s death, The Black Panther’s newspaper issue printed on September 13, 1969, included these two essays, along with an essay commemorating Ho’s death. However, Ho wrote these essays almost four decades before the Black Panther Party newspaper issues were printed in 1968-1970, during the height of the Vietnam War (1955-1975).

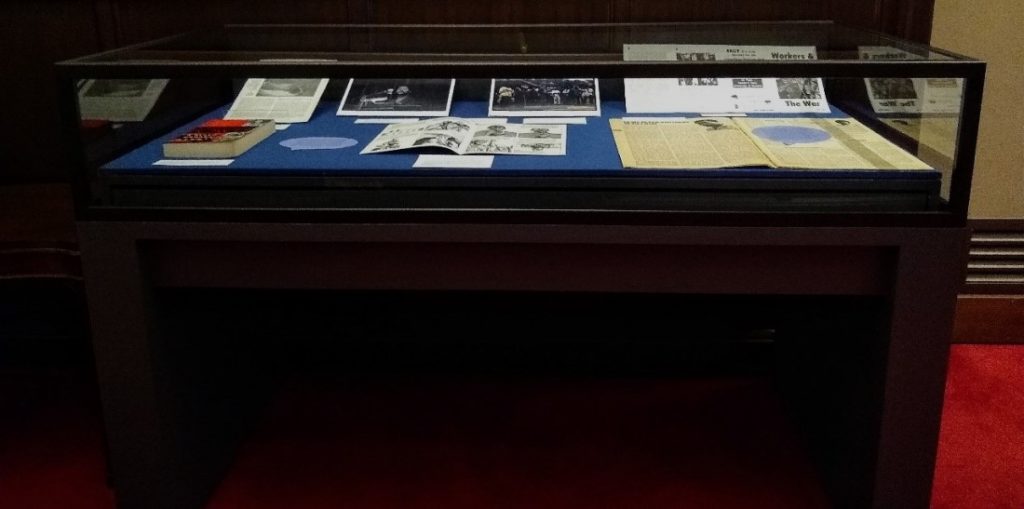

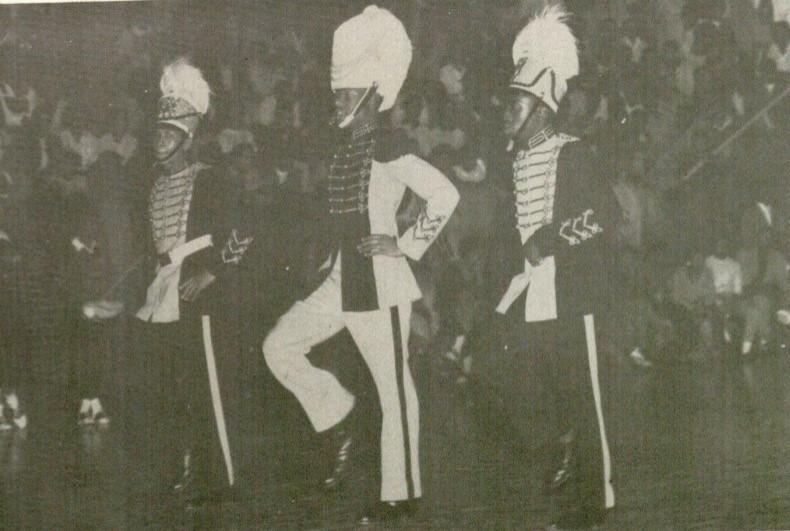

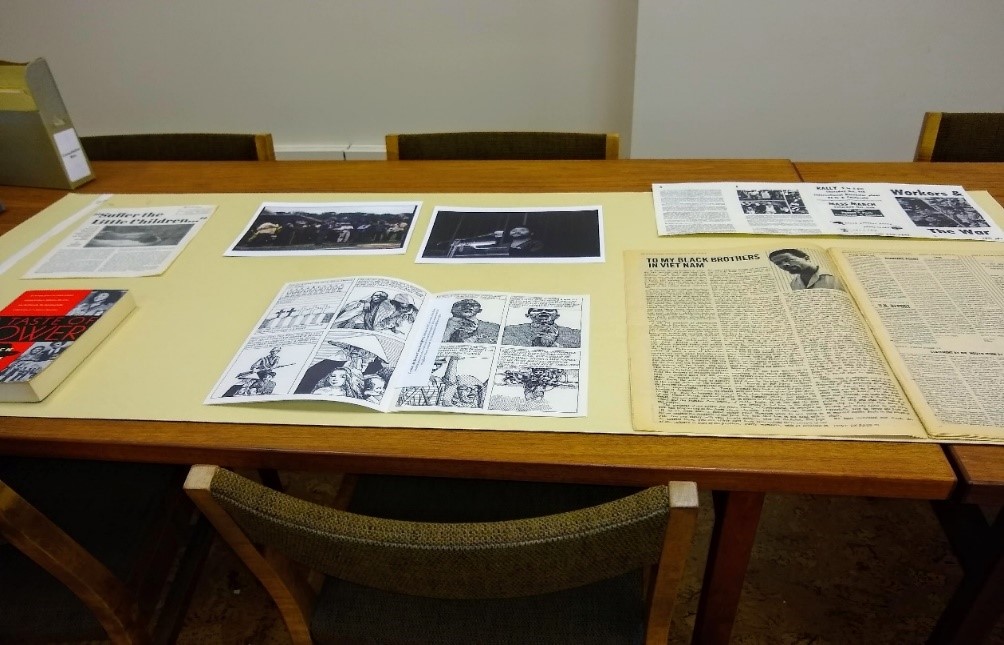

In addition, I also wanted to showcase the Black Panther Party’s anti-Vietnam propaganda and demonstrations. Once again, I found myself digging around in the Wilcox Collection. Among the items I chose for the second exhibit case include A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story by Elaine Brown (Call Number: RH WL C2210). Brown acted as the Black Panther’s Southern California Chapter’s Deputy Minister of Information. Brown also accompanied Eldridge Cleaver on his visits to North Vietnam, North Korea, and China.

One of my favorite items in the exhibit is Vietnam: An Anti-War Comic Book by Julian Bond, a founder of the Atlanta sit-in movement and of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The comic book is a piece of anti-war propaganda that highlights the connections between the struggles of African Americans and the Vietnamese people during the 1970s.

A huge thank you to Caitlin Donnelly Klepper, Angela Andres, and Letha Johnson for helping me at various stages of my exhibit, as well as to my supervisor, Deborah Dandridge, for supporting my interest in exploring a fascinating side of history that was unknown to me at the time that Kenneth Spencer Research Library provides in its variety of collections of resources. Another thank you to the staff and students at the Reading Room reference desk, who helped me with my requests.

Sophia Southard

African American Experience Collections Student Assistant