Spencer’s January-February Exhibit: “Building Tomorrow Today: Clinton Lake and the Flood of 1951”

I developed Spencer’s current short-term exhibit to compliment the research I conducted about Clinton Lake and the Wakarusa Museum as an undergraduate student. While writing my thesis paper last year, I used a lot of the materials featured in this exhibit as primary sources. I hope this blog post will elaborate more on the complex history of Clinton Lake and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers from a community perspective.

Originally passed by Congress in 1917, the Flood Control Act directed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to begin evaluating issues of flood control along tributaries of the Mississippi River. This included the longest tributary of the Mississippi River: the Missouri River, which feeds the Kansas (Kaw) River. On July 13, 1951, after a series of storms produced up to 16 inches of rain, the Kaw spilled over its banks. More than 115 cities along its path in eastern Kansas – most notably Topeka, Lawrence, and Kansas City – were flooded. In Lawrence, the river crested at 29.90 feet (11 feet above flood stage). The flood also washed out 1 million acres of land and nearly 10,000 farms. For many local community members, the Flood of 1951 represented a once-in-a-lifetime disaster. The flood forced 85,000 people to abandon their homes and amassed $760 million in damages (nearly $5 billion today).

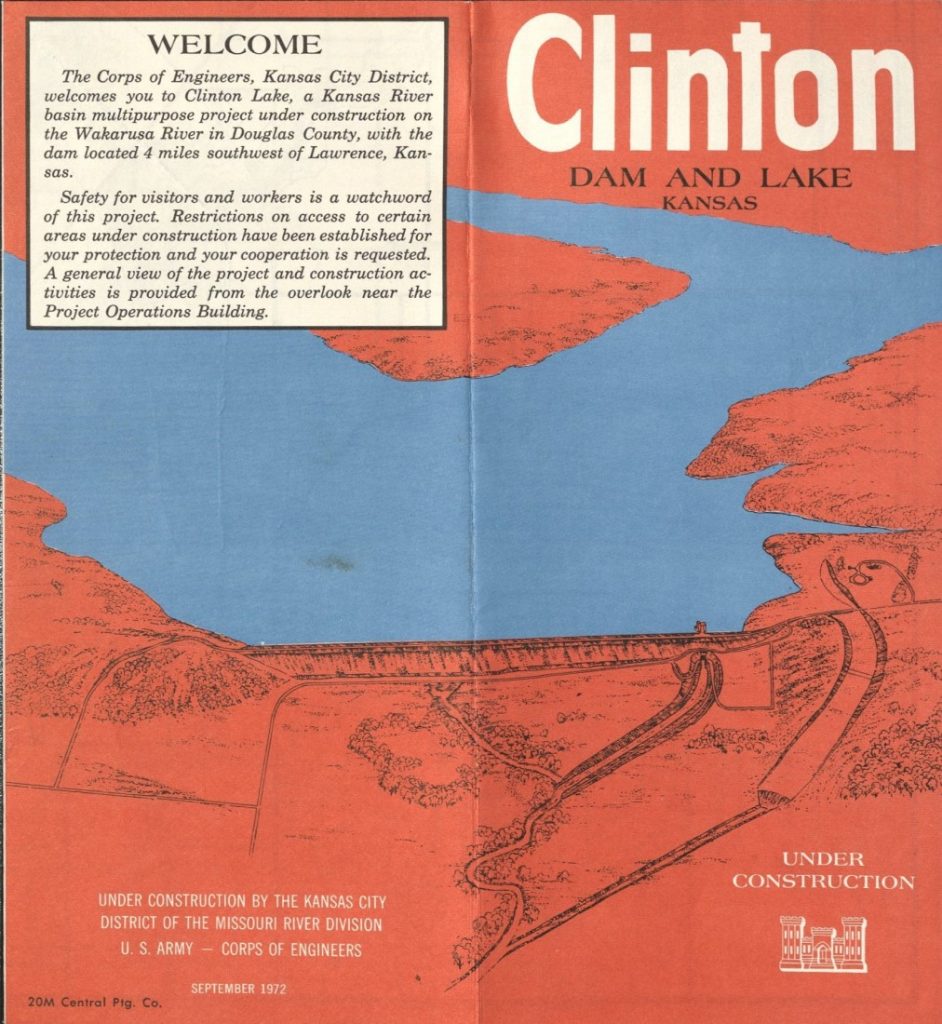

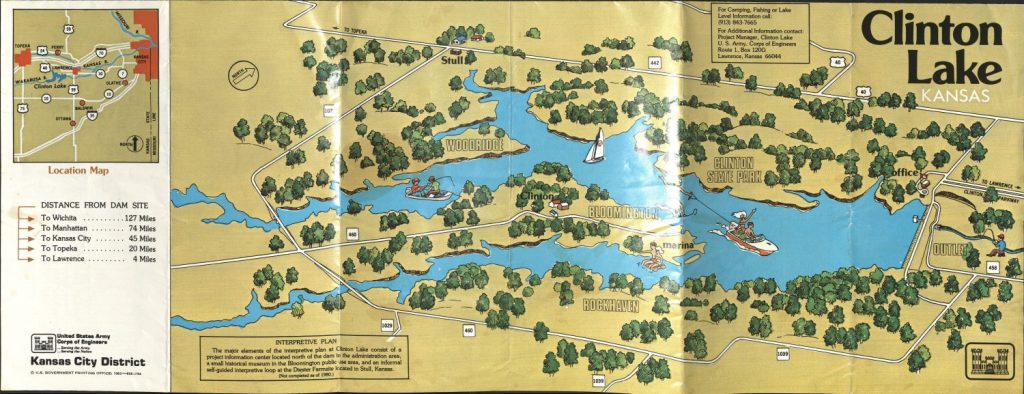

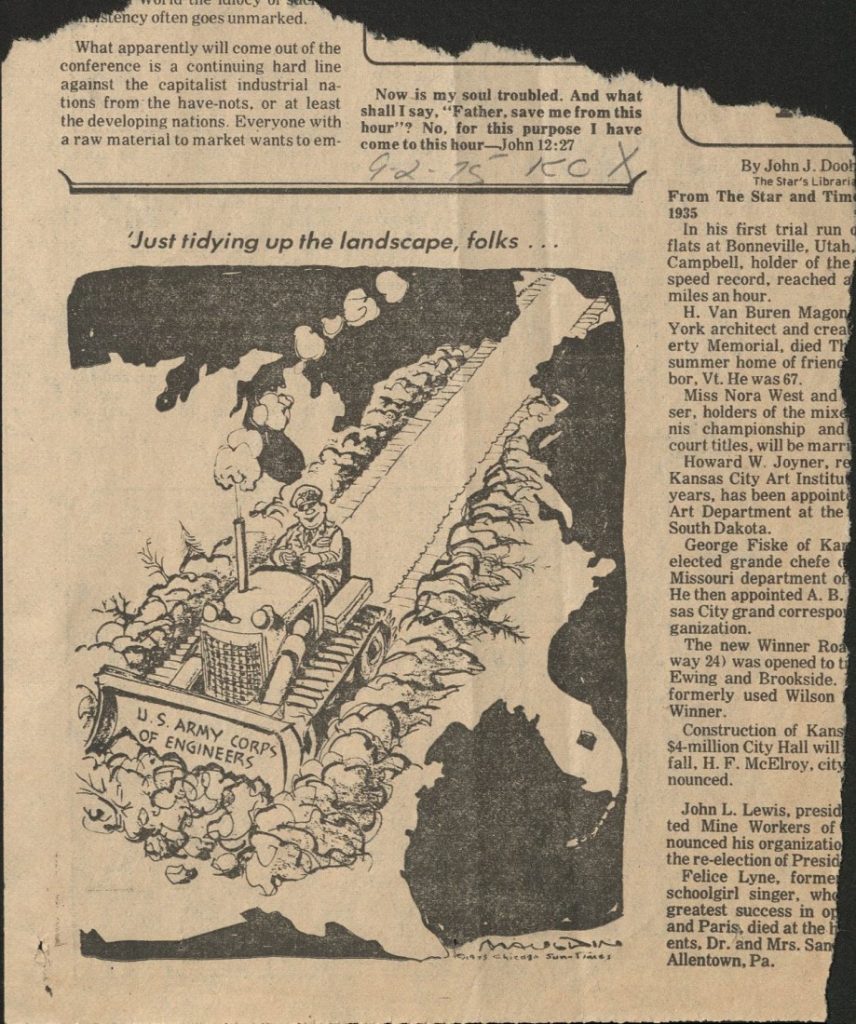

In response, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built a network of levees and reservoirs to prevent future flooding. The Flood Control Act of 1962 authorized funding to dam the Wakarusa River, a major tributary of the Kaw, and build Clinton Lake. In addition to flood control, Clinton Lake would also supply the city of Lawrence with water and provide a source of recreation for locals and tourists alike. Located southwest of Lawrence, Clinton Lake ushered in an era of excitement and uncertainty for the people of Douglas County. Despite protests from many Wakarusa River Valley citizens, the Corps of Engineers began buying land as early as 1968, and construction of the dam started in 1972.

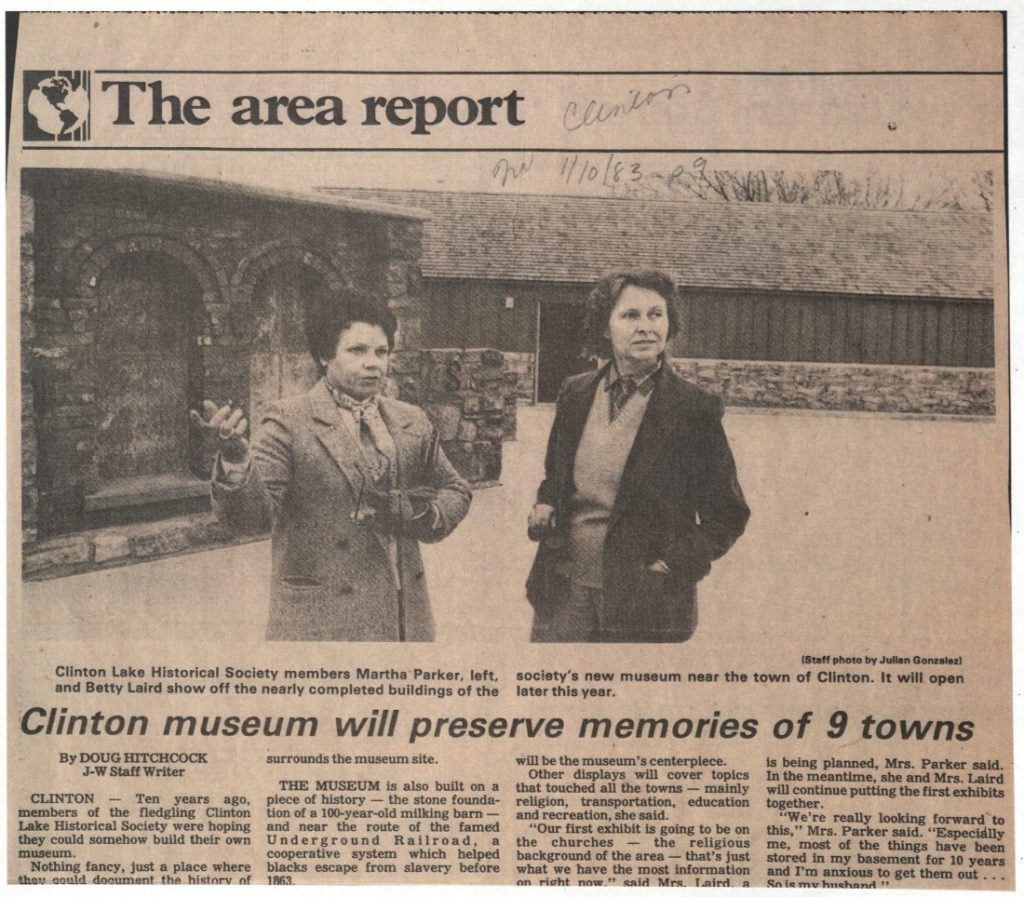

Swift action on behalf of the Corps of Engineers prompted local residents of the Wakarusa region to form the Clinton Lake Landowner’s Association, which advocated for the landownership rights of Wakarusa River Valley citizens. According to Martha Parker, a lifetime resident of Clinton and an active community member, “they did nothing but lie to you. We used to have a saying, ‘How can you tell a Corps man is lying? When his lips start moving.'” An auxiliary group, the Clinton Lake Historical Society (or CLHS) was formed alongside the Landowner’s Association with the goal of gathering and preserving the region’s history, which many feared would be lost forever beneath the lake. Many local community members held feelings of great anxiety about the proposed construction of Clinton Lake. This anxiety was not only rooted in an intense fear of the unknown, which often accompanies forced displacement, but the idea that the disappearance of regional history meant the erasure of one’s personal identity. “People just had no idea what was about to happen to them,” Parker explained. “Tons of people were selling all their belongings, their land, everything. I kept telling folks, don’t sell. Nobody listened.” With the support of the Landowner’s Association and the CLHS, Parker went on to establish the Clinton Lake Museum, known today as the Wakarusa River Valley Heritage Museum.

However, it is important to remember that Clinton Lake displaced more than just rural residents of the Wakarusa River Valley. The process of artificial lake building results in the forced displacement and subsequent migration of different groups of peoples at different moments in time. Yet this process cannot be viewed from a static perspective. Dispossession is not merely an event; it is a process that continues long after initial physical removal. Beginning in the 1800s, Native American nations located within the Wakarusa River Valley were removed from their federally promised lands in order to make room for white settlers. This included the Kaw Nation (whose ancestral homelands included the river valley) along with tribes relocated from the East (namely the Shawnee and Delaware). Therefore, Clinton Lake serves as a force of continuous dispossession. Flooding the land removes any future opportunity for communities, both Native and non-Native, to return to their homes and restore their sense of historical, cultural, and spiritual connection to that place.

This exhibit is free and open to the public in the North Gallery through February 28th.

Claire Cox

Public Services Student Assistant

KU Graduate Student in History

Tags: Claire Cox, Clinton Lake, environmental history, exhibition, Exhibitions, Flood of 1951, Kansas Collection, Kansas History, Lawrence, Lawrence KS