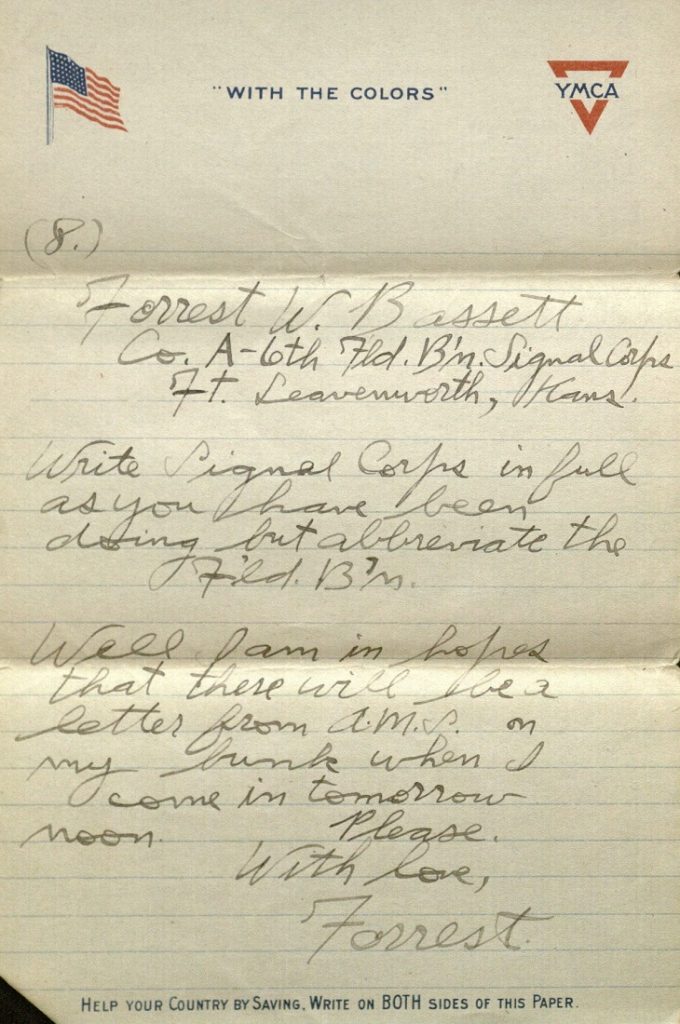

In honor of the centennial of World War I, we’re going to follow the experiences of one American soldier: nineteen-year-old Forrest W. Bassett, whose letters are held in Spencer’s Kansas Collection. Each Monday we’ll post a new entry, which will feature selected letters from Forrest to thirteen-year-old Ava Marie Shaw from that following week, one hundred years after he wrote them.

Forrest W. Bassett was born in Beloit, Wisconsin, on December 21, 1897 to Daniel F. and Ida V. Bassett. On July 20, 1917 he was sworn into military service at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri. Soon after, he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for training as a radio operator in Company A of the U. S. Signal Corps’ 6th Field Battalion.

Ava Marie Shaw was born in Chicago, Illinois, on October 12, 1903 to Robert and Esther Shaw. Both of Marie’s parents – and her three older siblings – were born in Wisconsin. By 1910 the family was living in Woodstock, Illinois, northwest of Chicago. By 1917 they were in Beloit.

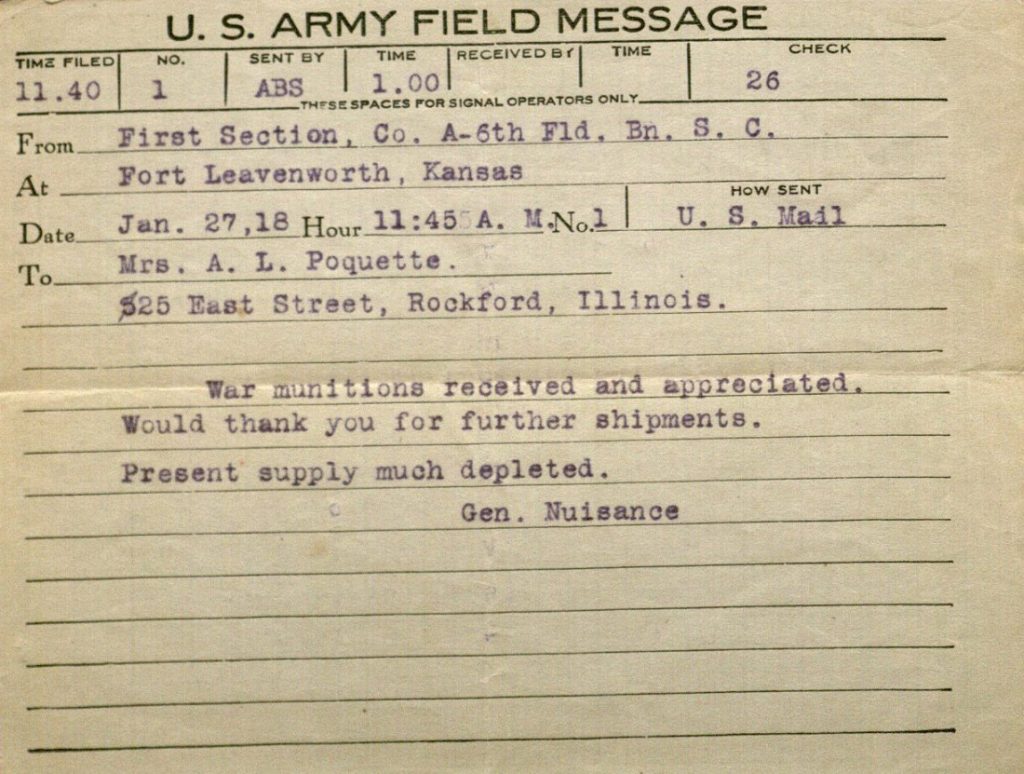

Frequently mentioned in the letters are Forrest’s older half-sister Blanche Treadway (born 1883), who had married Arthur Poquette in 1904, and Marie’s older sister Ethel (born 1896).

Highlights from this week’s letters include Forrest’s frozen ear (“this morning I froze the top of my left ear on my way to school”) and a dispute during guard duty (“[the Officer of the Day] criticised me for not turning out the guard when he came in sight…I was on duty from 10 to 12 P.M. and believe me I halted everyone strictly according to regulations”).

Jan 30, 1918

Dear Marie,

No letter came Monday nor Tuesday but three came today which made it all “fine” once more. You didn’t tell me exactly what an Earth Trodder is, so I am not justified in condemning the idea, however it doesn’t “listen” very good to me. I would be glad to get a fruit cake from you, so you better get Blanche to show you how to make one. I would eat it all myself, too – you see if the whole First Section were tied up with a “tummy-ache,” Co. “A” would be very seriously crippled.

Marie, don’t ever think for a minute that I will get tired of receiving your letters. I am at least as glad to get letters from you as you are to hear from me. But at the same time I think it would be better to write every other day as lots of times I get two letters on one day and none the preceding day.

Now please, little sweetheart, don’t think that I am tiring of you in the least.

We rode all afternoon yesterday. As soon as we hit the hills we left the main road and hit for the tall timber. You should have heard the hooting and yelling when we got in the woods. There is only about six inches of snow on the ground and the ground underneath is hard and slippery so we could not trot very much. Even at that we had a lot of fun. Our new first sergeant is a fine fellow. The other one was promoted and Sg’t. Ryan took his place. Sg’t. Ryan is the one that got kicked just below the eye by the same horse that tickled me on the jaw. I guess he will wear that scar all his life.

The Co. had a big test in semaphore yesterday. We are supposed to be able to send and receive five to eight words a minute in wig-wag and ten to fifteen words a minute in semaphore. The words are supposed to average five letters each. It is easy to read wig-wag as it is impossible to transmit very fast with a large flag. I didn’t take the test as I was down to the class at the Army Service School. During the wig-wag class period in the afternoon, I sent wig-wag at the rate of eleven words per minute for a few minutes, and when I quit I had a blister on the side of my hand. Sending semaphore is not so much work, but it takes lots of practice and a quick eye to get fifteen (that is 75 letters) a minute. This is about as fast as the average person writes. I can receive about twelve words and send about fifteen words per minute. Sometimes we semaphore French words and one is out of luck if he misses a single letter.

This morning I froze the top of my left ear on my way to school. It was hard and stiff so I kept it in the snow until it got soft then I turned the cold water facet on it. It is swollen up and is pretty blue and tender, but I guess it will be O.K. in a few days.

Tonight, Stock and I hiked to town – an auto delivery took us most of the way.

Tomorrow is muster day, so we will have Battalion inspection, which means that yours truly must scrub his leggins before he hits that little straw bunk.

Stock says “That’s enough Bassett, that’s enough” and I guess he is right, don’t you think so?

With love,

Forrest.

I know this writing is fierce but I had to hurry.

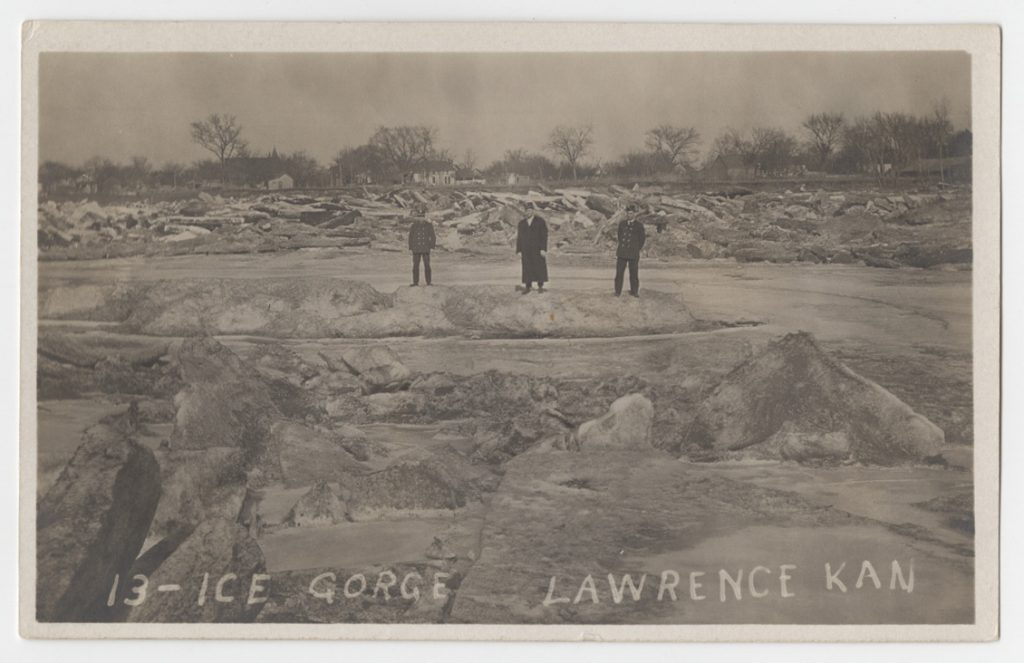

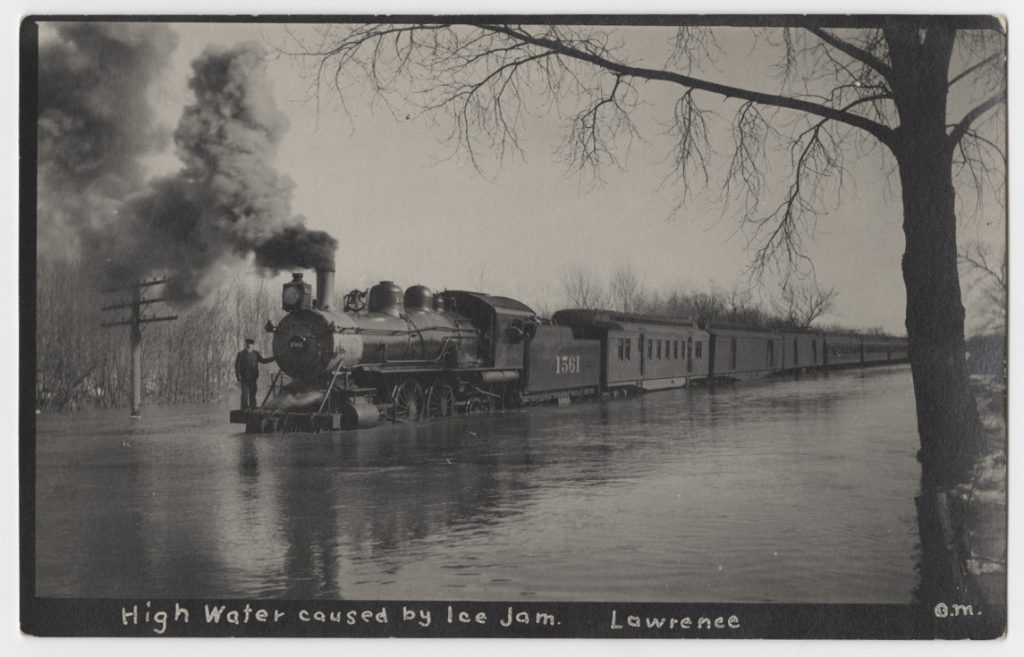

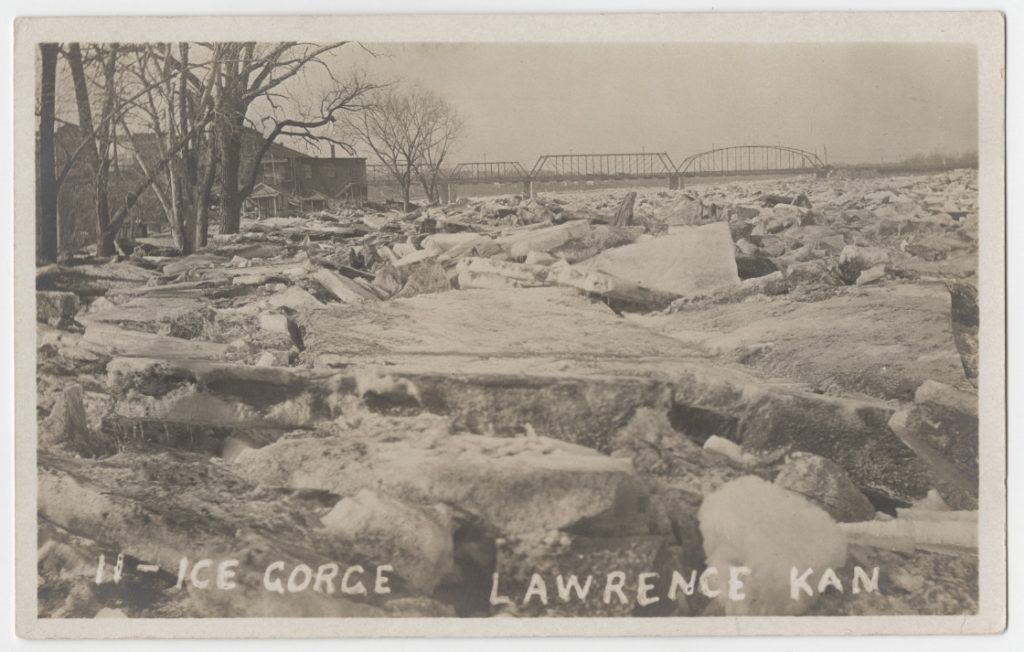

Click images to enlarge.

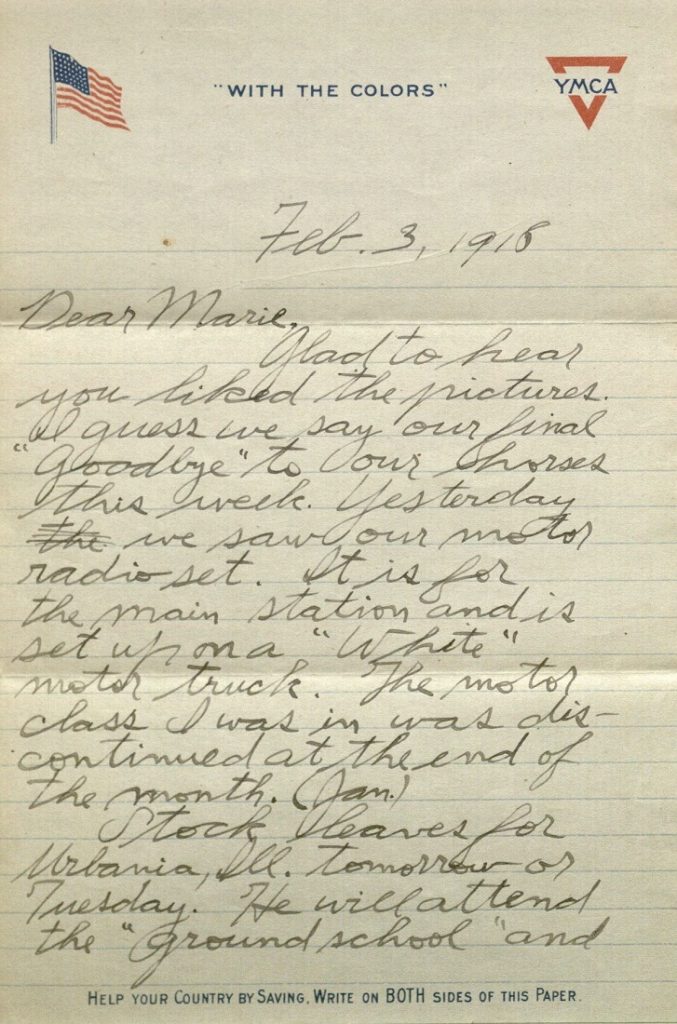

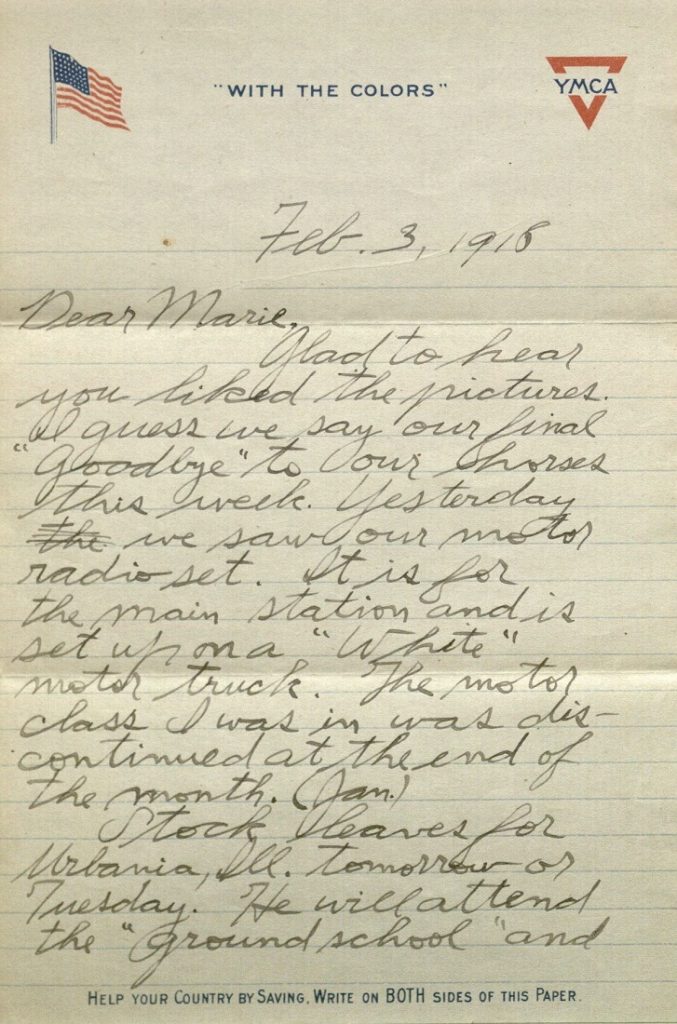

Feb. 3, 1918

Dear Marie,

Glad to hear you liked the pictures. I guess we say our final “Goodbye” to our horses this week. Yesterday we saw our motor radio set. It is for the main station and is set up on a “White” motor truck. The motor class I was in was discontinued at the end of the month. (Jan.)

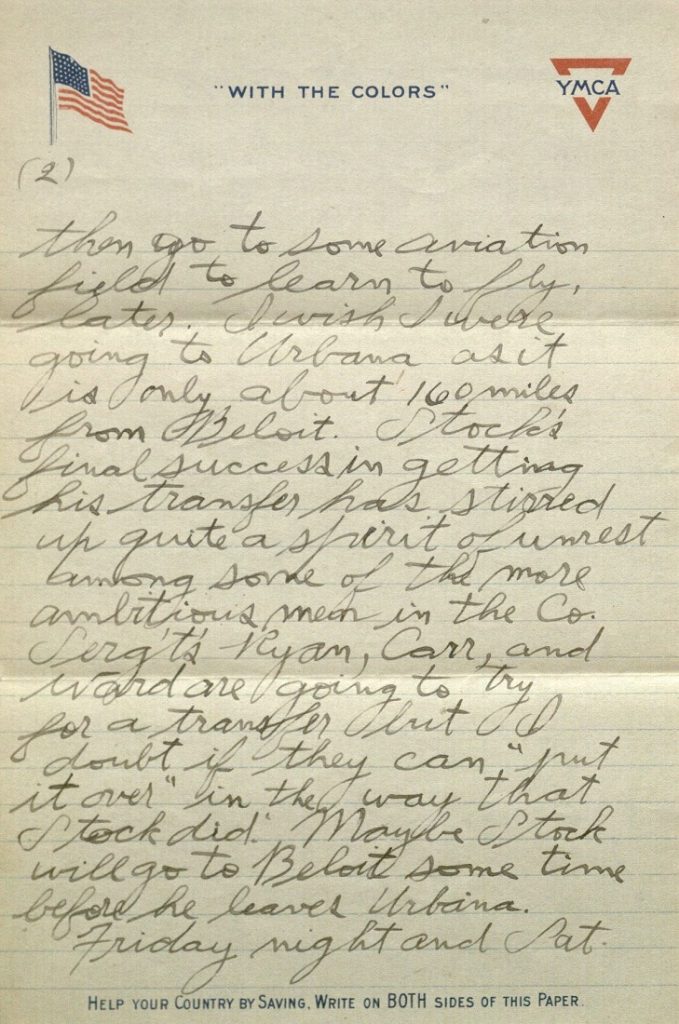

Stock leaves for Urbania, Ill. tomorrow or Tuesday. He will attend the “ground school” and then go to some aviation field to learn to fly, later. I wish I were going to Urbana as it is only about 160 miles from Beloit. Stock’s final success in getting his transfer has stirred up quite a spirit of unrest among some of the more ambitious men in the Co. Serg’ts Ryan, Carr, and Ward are going to try for a transfer but I doubt if they can “put it over” in the way that Stock did. Maybe Stock will go to Beloit some time before he leaves Urbana.

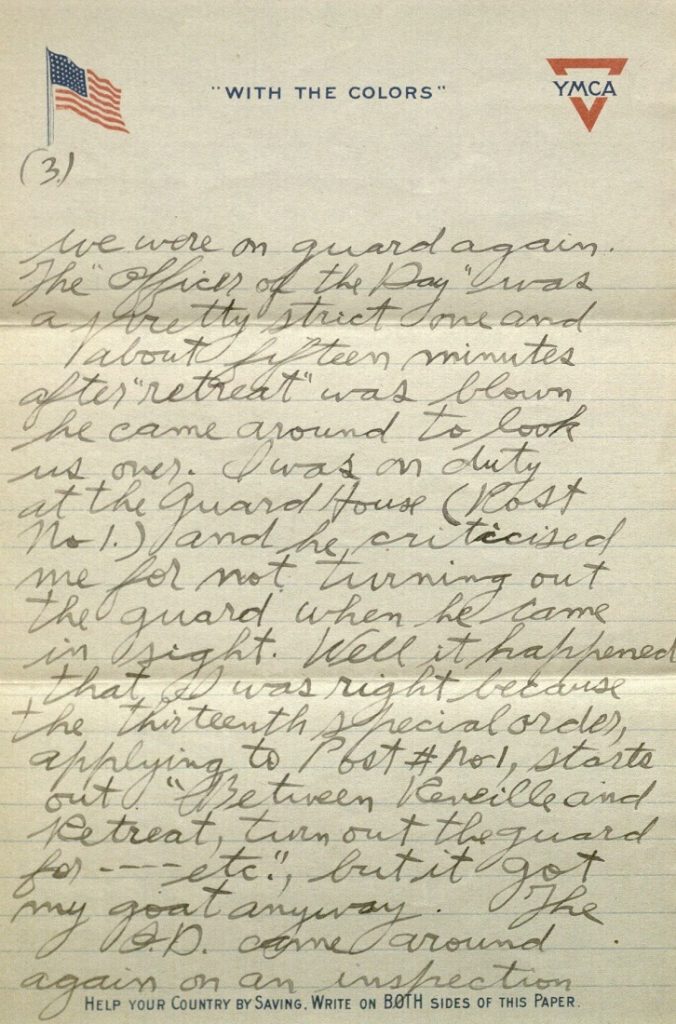

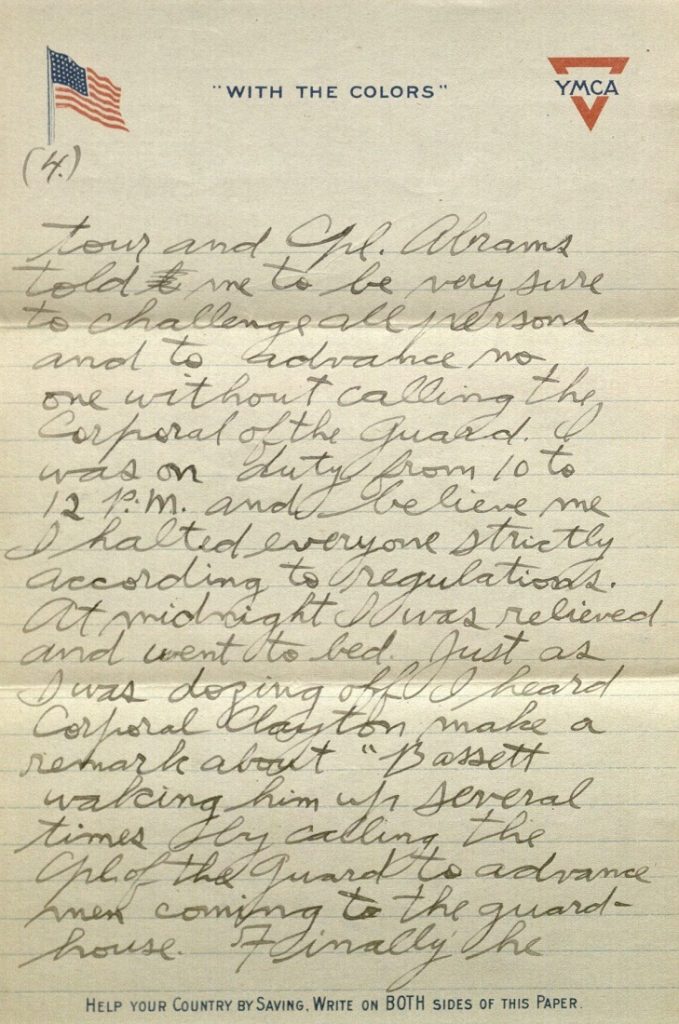

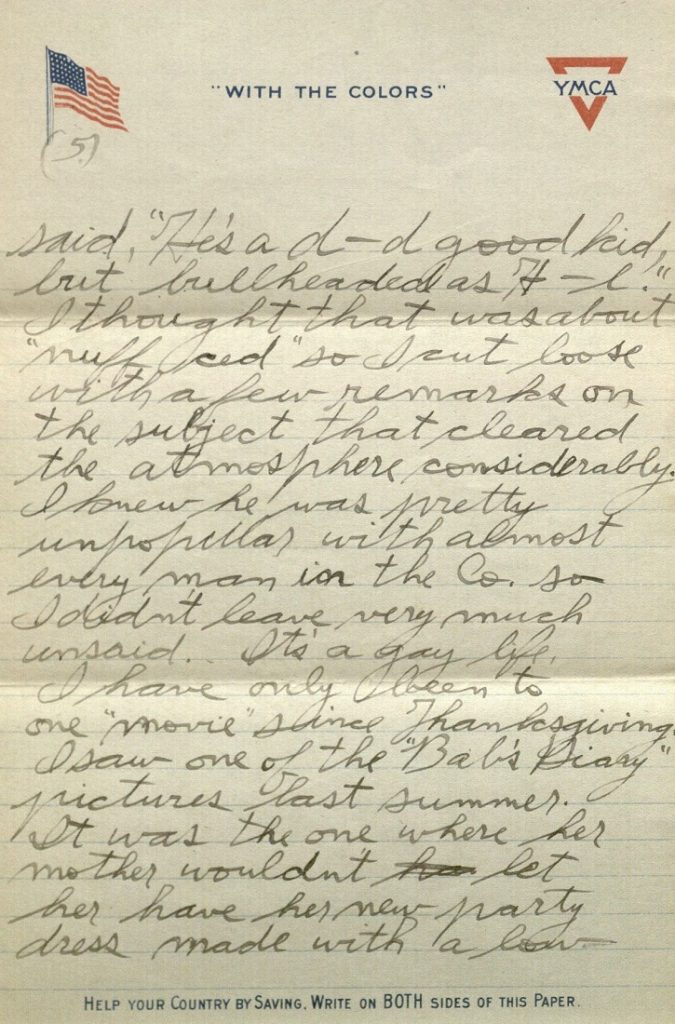

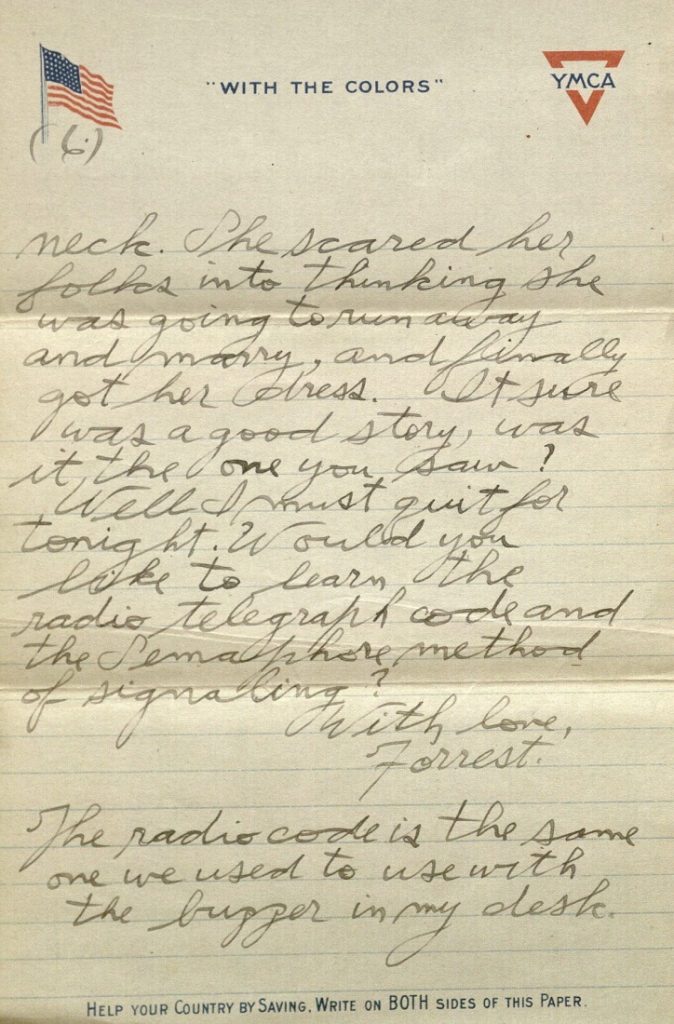

Friday night and Sat. we were on guard again. The “Officer of the Day” was a pretty strict one and about fifteen minutes after “retreat” was blown he came around to look us over. I was on duty at the Guard House (Post No 1.) and he criticised me for not turning out the guard when he came in sight. Well it happened that I was right because the thirteenth special order, applying to Post # No 1, starts out “Between Reveille and Retreat, turn out the guard for —- etc.”, but it got my goat anyway. The O.D. came around again on an inspection tour and Cpl. Abrams told me to be very sure to challenge all persons and to advance no one without calling the Corporal of the Guard. I was on duty from 10 to 12 P.M. and believe me I halted everyone strictly according to regulations. At midnight I was relieved and went to bed. Just as I was dozing off I heard Corporal Clayton make a remark about “Bassett waking him up several times by calling the Cpl. of the Guard to advance men coming to the guardhouse. Finally he said, “He’s a d-d good kid, but bullheaded as H—l.” I thought that was about “nuff ced” so I cut loose with a few remarks on the subject that cleared the atmosphere considerably. I knew he was pretty unpopular with almost every man in the Co. so I didn’t leave very much unsaid. It’s a gay life. I have only been to one “movie” since Thanksgiving. I saw one of the “Bab’s Diary” pictures last summer. It was the one where her mother wouldn’t let her have her new party dress made with a low neck. She scared her folks into thinking she was going to run away and marry, and finally got her dress. It sure was a good story, was it the one you saw? Well I must quit for tonight. Would you like to learn the radio telegraph code and the Semaphore method of signaling?

With love,

Forrest.

The radio code is the same one we used to use with the buzzer in my desk.

Meredith Huff

Public Services

Emma Piazza

Public Services Student Assistant