How Well Do You Know Your Irish Fairies?

March 14th, 2018With St. Patrick’s Day (March 17th) just around the corner, grocery stores and pubs are suddenly awash in four-leaf clovers, leprechauns, and other trappings of the commercial elements of the holiday. But why fixate on leprechauns when the world of Irish fairy folk is so much broader? How well do you know your Irish fairies?

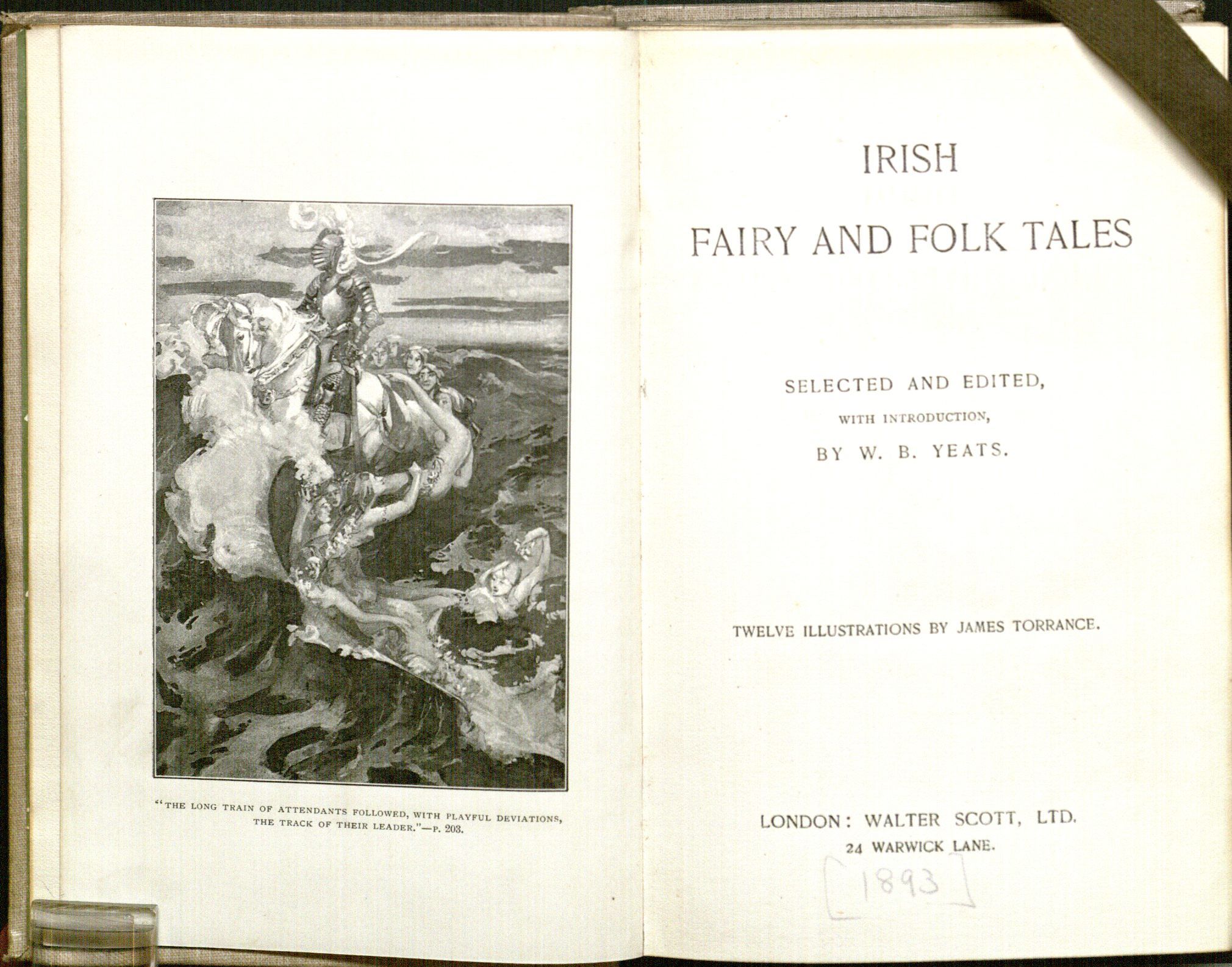

Title page and frontispiece from Yeats’s Irish Fairy and Folk Tales (1893),

an illustrated edition of his earlier Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry (1888).

Call Number: Yeats Y191. Click to enlarge.

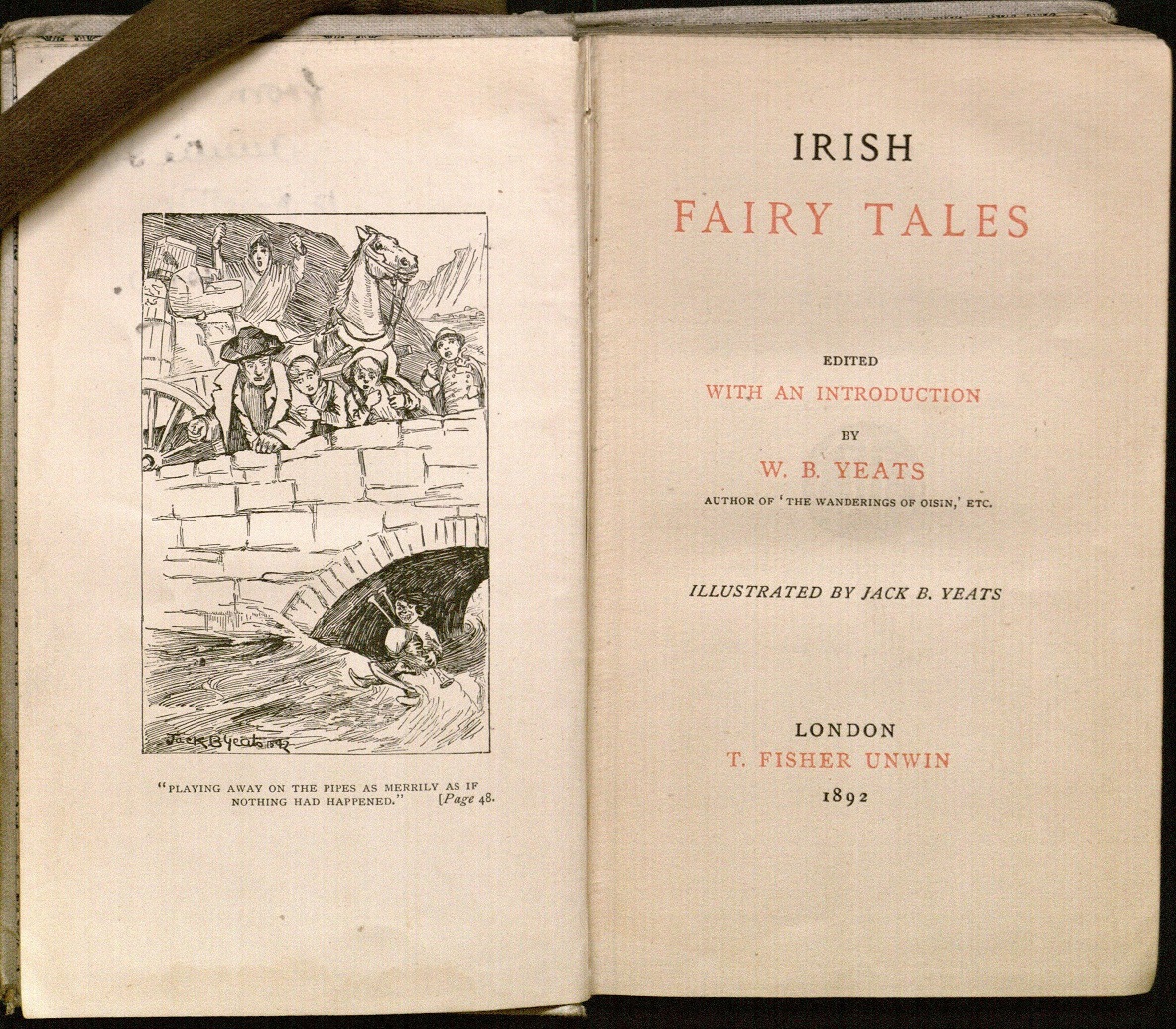

The Irish poet W. B. Yeats wrote more than once about Ireland’s different varieties of fairies. In 1888, when Yeats was in his early twenties, he edited a volume titled Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, which collected stories and poems by a variety of writers on the supernatural elements of Irish folklore. In organizing the book, he assembled its pieces under several headings, including “Ghosts,” “Giants,” and “Saints, Priests.” However, he accorded fairies a place of particular honor (as is their due in Irish folklore) by beginning the anthology with them and including several short section prefaces detailing their ways. When a few years later Yeats published the anthology Irish Fairy Tales (1892) for T. Fisher Unwin’s “Children’s Library Series,” he penned an appendix offering a “Classification of Irish Fairies.”

It would be a mistake to confuse one’s Leprechauns with one’s Merrows, since fairies — or the “gentry” as they prefer to be called — are easily offended. Thus in honor of St. Patrick’s Day, we share a shortened version of Yeats’s classification below.

Yeats begins his schema by dividing Irish fairydom into two classes: the sociable (or “Trooping Fairies,” as he named them in Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry) and the solitary. Of these two varieties, he writes, “The first are in the main kindly, and the second are full of uncharitableness.”

The Sociable Fairies “go about in troops, and quarrel, and make love, much as men and women do.” They are subdivided into two main types:

- The Sheoques (in Irish, Sidheog, “a little fairy”): Sheoques are land fairies, whom Yeats describes as “the spirits that haunt the sacred thornbushes and green raths.” While Sheoques are on the whole good, they have one “most malicious habit”: “They steal children and leave a withered fairy, a thousand or maybe two thousand years old, instead.” If this isn’t enough to inspire terror in Yeats’s child readers, he continues nonchalantly, “Now and then one hears of some real injury being done a person by the land fairies, but then it is nearly always deserved. They are said to have killed two people in the last six months in the County Down district where I am now staying. But then these persons had torn up thorn bushes belonging to the Sheoques.” I suspect Yeats’s proviso comes as little comfort to anyone who counts yardwork or landscaping among their chores!

- The Merrows (in Irish, Moruadh, “a sea maid)”: These are water fairies. Yeats writes that Thomas Croker, the author of Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland (1825), suggests that “[t]he men among them […] have green teeth, green hair, pigs’ eyes, and red noses; but their women are beautiful and prefer handsome fishermen to their green-haired lovers.” Yeats, himself, is more skeptical and comments that he has never “heard tell of this grotesque appearance of the male Merrows” and judges it “probably a merely local Munster tradition.”

What type of fairy is that? Title page for W. B. Yeats’ Irish Fairy Tales (1892) with frontispiece illustration

by Yeats’s brother, Jack B. Yeats. Call Number: Yeats Y194. Click image to enlarge.

Yeats next delineates nine subcategories of Solitary Fairies, whom he characterizes as “nearly all gloomy and terrible in some way”:

- The Lepricaun (in Irish, Leith bhrogan, “the one shoe maker”): Of this staple of St. Patrick’s Day, Yeats writes, “This creature is seen sitting under a hedge mending a shoe, and one who catches him can make him deliver up his crocks of gold, for he is a miser of great wealth; but if you take your eyes off him the creature vanishes like smoke.” Don’t expect to find him in outfitted in green, though. Yeats notes that according to McAnally, author of Irish Wonders (1888), the leprechaun wears “a red coat with seven buttons in each row, and a cocked-hat, on the point of which he sometimes spins like a top.” One wonders if Yeats’s leprechaun might also be responsible for other types of mischief, such as the fact that Yeats spells his name “Lepracaun“ in Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry (1888) but “Lepricaun“ in Irish Fairy Tales (1892).

- The Cleuricaun (in Irish, Clobltair-cean): Yeats notes that some writers “consider this to be another name for the Lepricaun, given him when he has laid aside his shoe-making at night and goes on the spree.” These fairies’ enthusiasms include “robbing wine-cellars” and “riding sheep and shepherds’ dogs.”

- The Gonconer or Ganconagh (in Irish, Gean-canogh, i.e. love-talker): A “creature of the Lepricaun type” who, unlike his industrious cobbler brethren, is idle. Yeats notes he “appears in lonely valleys, always with a pipe in his mouth, and spends his time in making love to shepherdesses and milkmaids.”

[Would Yeats have concurred that modern St. Patrick’s Day celebrants perhaps possesses a touch of the Clericaun and Gonconer in their (admittedly sociable) revelry?]

- The Far Darrig (in Irish, Fear Dearg, i.e. red man): This fairy is “the practical joker of the other world” whom Yeats deems a “lubberly wretch.” Like the Pooka (below), “he presides over evil dreams.”

- The Pooka (in Irish, Púca, “a word derived by some from poc, a he-goat)”: Yeats notes that this fairy usually takes the shape of “a horse, a bull, a goat, eagle, or ass” and “most likely never appeared in human form.” He is of the “family of the nightmare” and “[h]is delight is to get a rider, whom he rushes with through ditches and rivers and over mountains, and shakes off in the gray of morning.”

- The Dullahan: This fairy must be a relative of the headless horseman who appears in Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” Yeats explains that he “has no head, or carries it under his arm,” and can be seen “driving a black coach called coach-a-bower (Ir. Coite-bodhar), drawn by headless horses.” If you hear his carriage rumble by, keep your door closed, for if you open it “a basin of blood is thrown in your face.” As one might guess from such an unwelcome greeting, the Dullahan is “an omen of death to the houses where it pauses.”

- The Leanhaun Shee (in Irish, Leanhaunsidhe, i.e. fairy mistress ): Yeats writes, “This spirit seeks the love of men. If they refuse, she is their slave; if they consent, they are hers, and can only escape by finding one to take their place. Her lovers waste away, for she lives on their life.” He also refers to her as the “Gaelic muse” and asserts that many of the Gaelic poets have had a Leanhaun Shee, “for she gives inspiration to her slaves.”

- The Far Gorta (man of hunger): An emaciated fairy who “goes through the land in famine time, begging and bring good luck to the giver.”

- The Banshee (in Irish, Bean-sidhe, i.e. fairy woman): In addition to the Leprechaun, the Banshee is perhaps the other Irish fairy who will be familiar to American audiences. Yeats notes that like the Far Gorta (and unlike the other solitary fairies), the Banshee possesses a “generally good disposition.” He suggests that perhaps she isn’t really a solitary fairy after all, “but a sociable fairy grown solitary through much sorrow.” The Banshee wails over the impending the death of “a member of some old Irish family.” Yeats observes, “Sometimes she is an enemy of the house and screams with triumph, but more often a friend.” In Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, Yeats remarks that the “keen [caoine], the funeral cry of the peasantry, is said to be an imitation of her cry.” If more than one Banshee arrives to wail, it is a sign the dying person “must have been very holy or very brave.”

Yeats closes his taxonomy by alluding to other varieties of fairies “of which too little is known to give them each a separate mention.” Among these are the Bo men fairies of County Down, whom Yeats suggests are “Scotch fairies imported by Scotch settlers.” This last detail offers us some hope of encountering Irish fairies on American shores, for its seems that, like us, fairy folk can travel.

To read Yeats’s “Classification of Irish Fairies” in full click here to access the appendix in PDF form or visit Spencer Research Library’s reading room to explore further writings on the topic by Yeats, Lady Wilde, Thomas Crocker, Douglas Hyde, and others in Spencer’s Irish Collections. Happy St. Patrick’s Day!

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian