August 29th, 2014 The late marsupialist John A.W. Kirsch was interviewed by a local (Peruvian) newspaper while on a collecting trip in South America back at the end of the 1960s. He described the kinds of animals he was looking for and was shocked to see the headline a few days later: KANGAROOS ON MACHU PICCHU.

While it’s true that the mammal group we call marsupials includes the kangaroos, wallabies, wombats, koalas, and bandicoots that are usually associated with Australia, and that the New World once did boast a rich and diverse marsupial fauna, most of the New World forms are now extinct and, sad to say, there are no kangaroos on Machu Picchu.

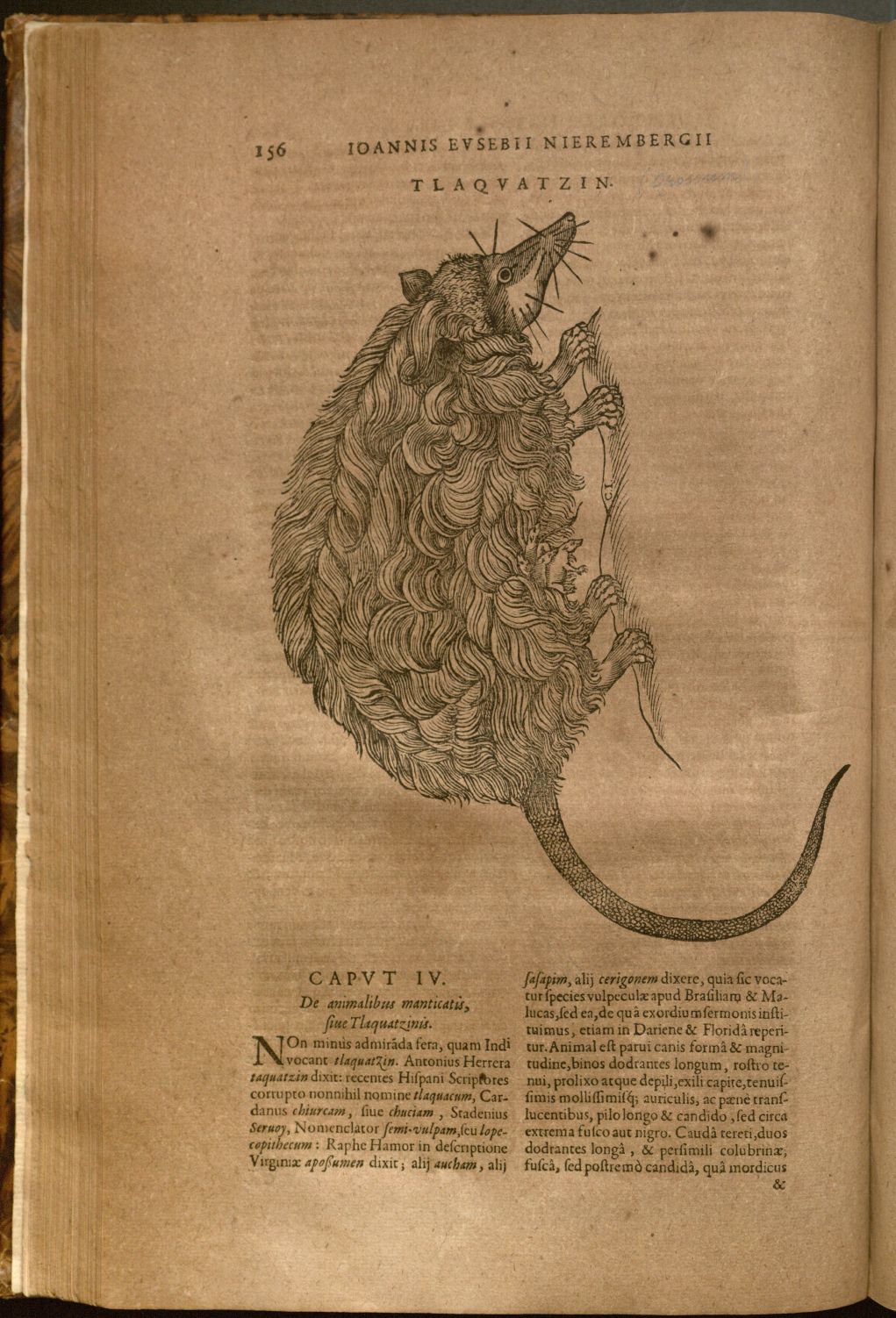

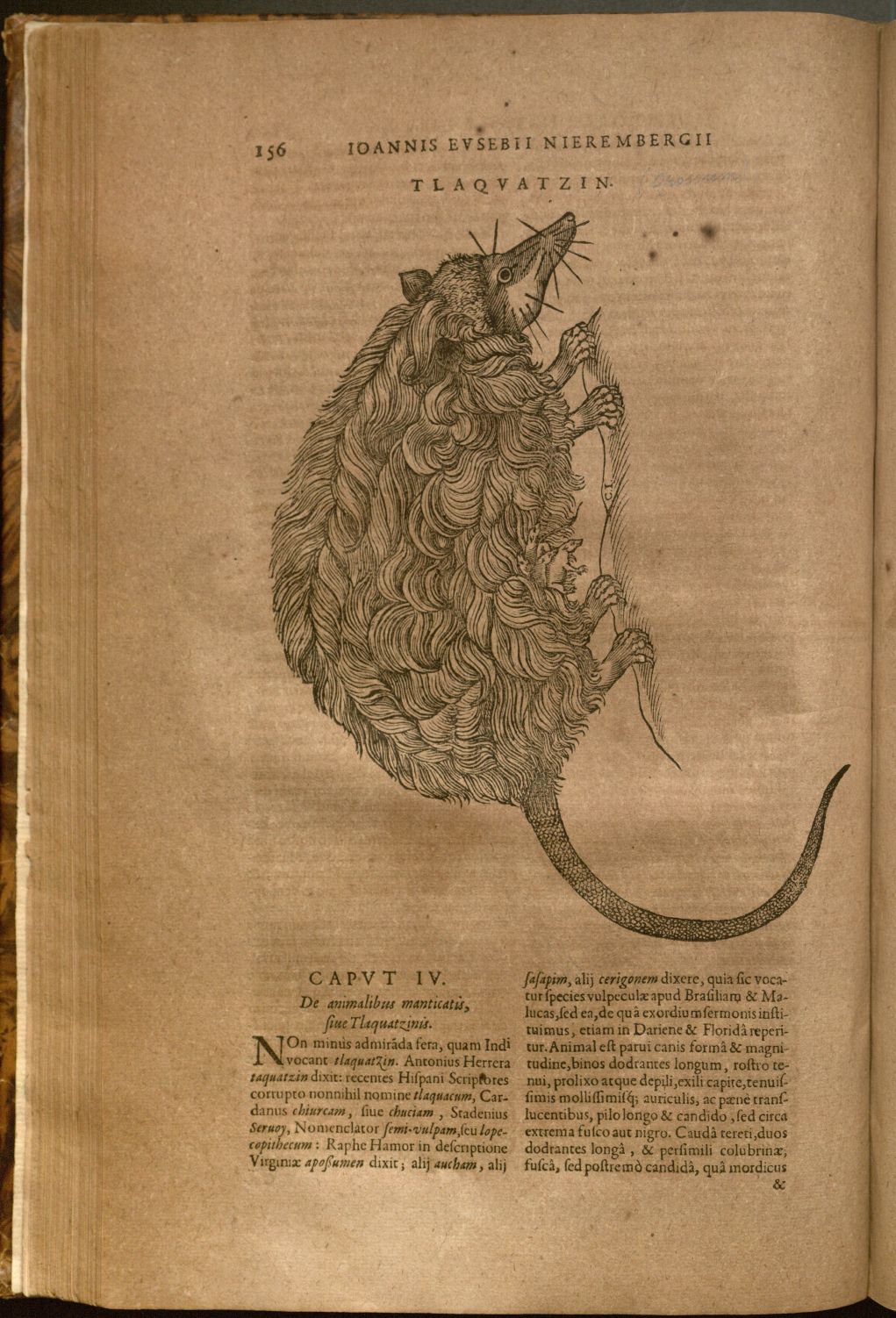

Opossums (and yes, there are several pictured above): Juan Eusebio Nieremberg (1595-1658). Historia naturae. Antverpiae: ex Officina Plantiniana Balthasaris Moreti, 1635. Call Number: Summerfield E1105. Click image to enlarge (and reveal the well-camouflaged opossum young.)

The marsupial heyday began to end circa three million years ago when a land bridge over the Isthmus of Panama provided for northern migration of animals including the ancestors of our familiar opossum, who dates back to around 35 million years ago and looks today pretty much the same as he did then. During the same period, some of the northern placental mammals migrated south over the same land-bridge. Thus, for example, it appears that the placental sabre-toothed tiger from the North began to compete with the marsupial sabre-toothed tiger and soon put him on the road to extinction. But the marsupials are survivors, nevertheless, and the American opossum, the only one of the family in North America, is just one of seventy some opossum species to survive; the ‘possum family is restricted to the New World, and except for Didelphis virginiana, whose range extends from southern Canada into Central America, the rest of the family is restricted to Central and South America.

Earlier travel accounts and herbals had described the plants and animals of the New World, but Juan Eusebio Nieremberg’s account was the first comprehensive natural history of the area, dealing primarily with Mexico and the West Indies. This illustration of the Virginia or American opossum is the earliest printed portrait of the earliest discovered (by Europeans, at least) marsupial anywhere.

Sally Haines

Rare Books Cataloger

Adapted from her Kenneth Spencer Research Library exhibit, The Haunted Forest: New World Plants & Animals (1992).

Tags: Haunted Forest (exhibition), Historia naturae (1635), Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, marsupials, natural history, Opossums, Sally Haines

Posted in Exhibitions, Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »

February 8th, 2013 Pliny the Elder, that most famous and trustworthy of the ancient Roman naturalists, was too curious about natural phenomena for his own good; as every school-child knows, he was asphyxiated by volcanic dust and gasses when he went to investigate the same eruption of Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii in 79 A.D.

Aristotle and Pliny are the names that come to mind when we think of naturalists of the ancient world. Aristotle was the originator of biological classification; in contrast to the Biblical groups of animals as “clean” or “unclean,” he established categories based primarily on anatomical and other observable characteristics. His was a coherent natural system. The Spencer Library has several editions of Aristotle’s Historia Animalium, the earliest printed in 1493.

The only surviving work of Pliny is the encylopedic Naturalis Historia, the earliest extant manuscript of which dates from the 10th century.** His work was a compilation of all the animals and plants that he knew of or had heard about, and contained little that was original. He was not yet a systematist and there was little order in his arrangement, but we have him to thank for the survival of some of the writings of others, and he is regarded as THE authority on natural history from the days of Imperial Rome through the Middle Ages.

Pliny, the Elder. Caji Plinii Secundi … Bücher und Schrifften von der Natur, Art und Eigenschafft der Creaturen oder Geschöpfe Gottes … [Naturalis historia. German.] Franckfurt am Mayn : Feyrabend und Hüter, 1565. Call Number: Summerfield E1059. Click images to enlarge.

Beginning with the earliest printing of Pliny in 1469, there were at least 42 printings in numerous languages, including English, before 1536. The Kenneth Spencer Research Library houses 21 separate editions produced between 1476 and 1685. This German version contains books 7-10 and part of book 11. The translation was made by J. Heyden Eifflender von Dhaun and is illustrated with woodcuts by Jost Amman and Virgil Solis.

Sally Haines

Rare Books Cataloger

Adapted from her Spencer Research Library exhibit and catalog, Slithy Toves: Illustrated Classic Herpetological Books at the University of Kansas in Pictures and Conservations

**Author’s Note: This is the information we had at the time of publication of Slithy Toves in 2000; Mr. Roger Pearse has recently pointed out that in fact there do exist fragments of 5th century codices of Pliny.

Tags: Aristotle, Bücher und Schrifften von der Natur, classification, Crocodiles, Historia Animalium, J. Heyden Eifflender von Dhaun, Jost Amman, natural history, Naturalis Historia, Pliny the Elder, Sally Haines, Slithy Toves, Virgil Solis

Posted in Exhibitions, Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »

October 5th, 2012 In his book on the viper, Nouvelles experiences sur la vipere, Parisian apothecary Moyse (or Moïse) Charas takes to task Italian physician, naturalist, and poet Francesco Redi (1626-1697), for his scientific study of viper bites, the first such research ever. Charas was of the opinion (and not alone in it) that venom per se was harmless and that death was caused by poisonous spirits injected into the victim by the mind of an infuriated viper. Charas’s title-page shows two vipers entwined as in the caduceus, or staff of Mercury, one of the symbols of the medical profession. The Aesculapian staff, after the Greco-Roman God of medicine and healing, Aesculapius, is branched at the top with a single snake twined around it; it is the official insignia of the American Medical Association.

Charas, Moyse (1618-1698). Nouvelles experiences sur la vipere.

A Paris: chez l’auteur et Olivier de Varennes, 1669. Ellis Omnia B30.

Click image to enlarge.

Charas recommended viper as a staple of the diet and as a preventive and cure for a good many diseases. His 17th century compatriot and contemporary Pierre Pomet (1658-1699) recommended distilled salts of viper to prevent measles, smallpox, plague, and scurvy, and to cure gout, rheumatisum, and venereal disease. Viper heart was prescribed for mealcholia. In another book, Trakat über den Theriak, Charas extols theriac, an anti-leprosy medicine made from powdered snake and used since antiquity; in medieval Europe the powder was formed into tablets, stamped with a snake image, and used against the bubonic plague. But that ain’t nothin’; our American frontiersmen gladly bought greasy-kid-stuff from snake-oil salesmen who took their money and swore the oil would grow hair back on their heads and cure the goiter to boot.

On the added engraved title-page of the Spencer Library’s copy (pictured above) is the inscription of the book’s former owner, French pharmacist and botanist Jean Leon Soubeiran (1827-1892). Soubeiran was the author of books on materia medica from all the kingdoms of nature–plant, animal, and mineral–including one on the venom of poisonous snakes.

Sally Haines

Rare Books Cataloger

Adapted from her Spencer Research Library exhibit and catalog, Slithy Toves: Illustrated Classic Herpetological Books at the University of Kansas in Pictures and Conservations.

Tags: history of science, Jean Leon Soubeiran, Moyse Charas, natural history, Nouvelles experiences sur la vipere, Sally Haines, snakes, Vipers

Posted in Exhibitions, Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »

September 7th, 2012 The bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, is the largest frog in North America. However, even as flat as he looks on this plate, he’s an unlikely candidate for road pizza on your plate, because although he’s an amphibian, the adult bullfrog tends to stay in his moist habitat and not to venture out onto dry land. Unfortunately for him, in this country, he’s one of the few species large enough to provide a satisfactory meal of frog legs for Homo sapiens.

![Plate from James Petiver's Gazophylacii Naturae & Artis in qua animalia [...] Plate from James Petiver's Gazophylacii Naturae & Artis in qua animalia [...]](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/EllisAves_E116_item2.jpg)

James Petiver (1663 [or 4]-1718). Gazophylacii naturæ & artis,: decas prima-[decima]. In quâ animalia,

quadrupeda, aves, pisces, reptilia, […] descriptionibus breviubs & iconibus illustrantur. Londonii: Ex Officinâ

Christ. Bateman ad insignia Bibliæ & Coronæ, vico vulgo dict. Pater-Noster-Row., MDCCII. [1702-1706?]

Call Number: Ellis Aves E116 item 2. Click image to enlarge.

James Petiver, known primarily as a botanist and as one of the founders of British entomology, went to considerable expense to have ships’ captains and surgeons supply him with specimens of natural history from around the world for his museum. In the Gazophylacium, one of Petiver’s rarest and most interesting productions, the figures of reptiles and amphibians, plants, shells, insects, birds, and other animals are displayed together on the same plate. It was the intention of both author and publisher that the text be pasted down on the versos of the plates facing the appropriate plate, with dedication mounted at the foot of each, as in the Spencer Library’s copy; however, in most states of the work, text is simply printed on the back of each plate.

Sally Haines

Rare Books Cataloger

Adapted from her Spencer Research Library exhibit and catalog, Slithy Toves: Illustrated Classic Herpetological Books at the University of Kansas in Pictures and Conservations

Tags: Bullfrogs, Gazophylacii Naturae & Artis, James Petiver, natural history, Rana catesbeiana, Sally Haines

Posted in Exhibitions, Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »

July 13th, 2012 No kidding, there really was a seven-headed hydra, and it took an 18th century St. George to slay it: Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus. In Hamburg, Germany, Linnaeus exposed as a fake the specimen of a seven-headed hydra that its owner, the mayor of Hamburg, had been trying to sell–and his asking price was high. This curious critter had been looted from a church in 1648 after the Battle of Prague and had come into the mayor’s hands. Even the king of Denmark had supposedly made an unsuccessful bid for it. The mayor found he was having to lower his price, which had been falling steadily when Linnaeus tactlessly published his findings that the jaws and feet were those of a weasel and that carefully joined snake-skins covered the body. Fearing the mayor’s revenge for rendering his hydra worthless, the Swede made a hasty exit from the city. The Kenneth Spencer Research Library holds a significant collection of Linnaeus and Linnaeana (follow the link and scroll down for a brief description of the collection).

Historiae Naturalis de Serpentibus, by Joannes Jonstonus (1603-1675). Heilbronnae: apud Franciscum

Iosephum Eckebrecht, 1757. Call Number: Ellis Omnia E26 item 2. (Click image to enlarge.)

Jonstonus (or Jonston, sometimes Johnstone) was a naturalist of Scottish descent born in Poland. After studying botany and medicine at Cambridge, he settled in Leiden in order to indulge his interest in natural history. His writings are criticized as laborious compilations, and the copper-plate engravings are mostly copies from Belon, Rondelet, Gessner, and others.

Sally Haines

Rare Books Cataloger

Adapted from her Spencer Research Library exhibit and catalog, Slithy Toves: Illustrated Classic Herpetological Books at the University of Kansas in Pictures and Conservations (print copies of the exhibition catalog are available at KU Libraries).

Tags: Carl Linneaus, Historiae Naturalis de Serpentibus, Hydras, Joannes Jonstonus, mythical creatures, natural history, Sally Haines

Posted in Exhibitions, Special Collections |

No Comments Yet »

![Plate from James Petiver's Gazophylacii Naturae & Artis in qua animalia [...] Plate from James Petiver's Gazophylacii Naturae & Artis in qua animalia [...]](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/EllisAves_E116_item2.jpg)