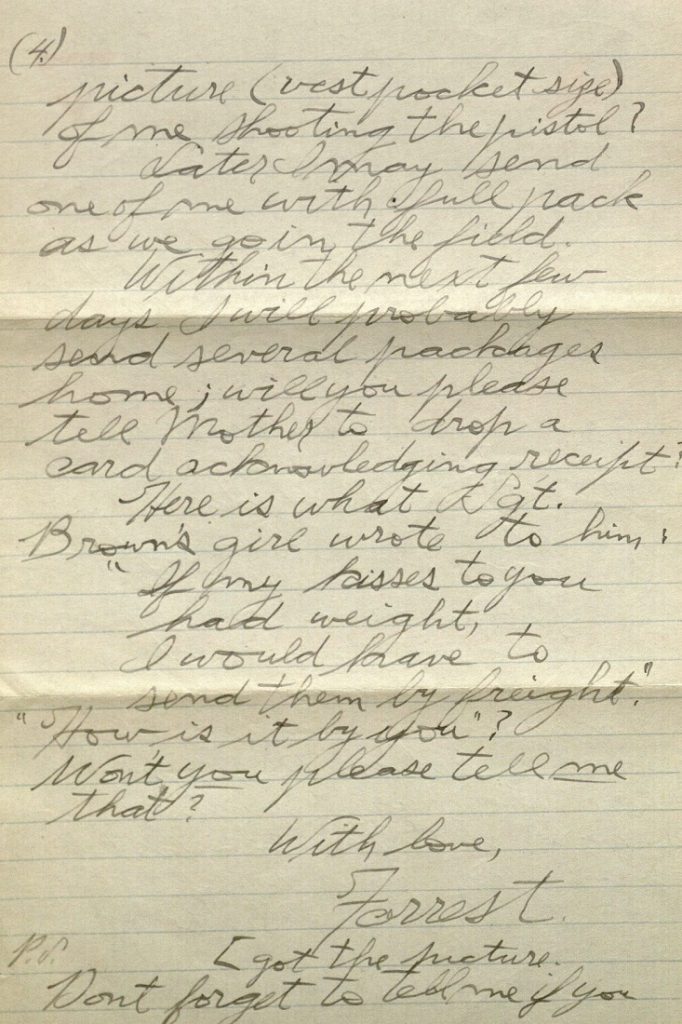

The diversity of the Spencer Research Library collections is explored through the description of a search process related to a research question or theme.

After having two encounters with items called “blue books” in as many days, I wondered what the origin of the term blue book is. I turned to a resource found in the Reference section of the Spencer Reading Room, i.e., the Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language. According to this edition published in 1959, a blue book is defined as follows:

- In England, a parliamentary publication, so called from its blue paper covers; in some other countries, any similar official publication. Hence, also, an authoritative report or manual issued by a department, organization, or party.

- Colloq., U.S. a A register or directory of persons of social prominence. b In certain colleges, a blue-covered booklet used for writing examinations.

- [caps.] Trade-mark for a guidebook entitled Official Automobile Blue Book, showing roads, routes, etc., esp. for automobile tourists; also [sometimes not caps.], the guidebook itself. U.S.

Would it be possible to find an example of each type of blue book described in the dictionary definition by looking solely in the collections available at the Spencer Library? I wanted to find out.

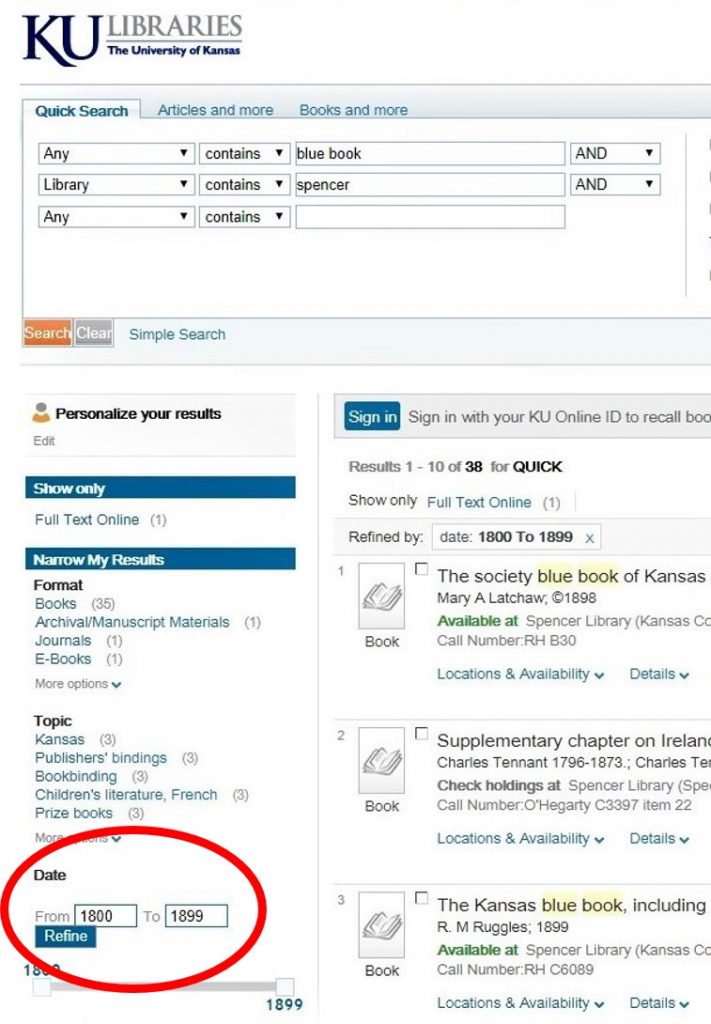

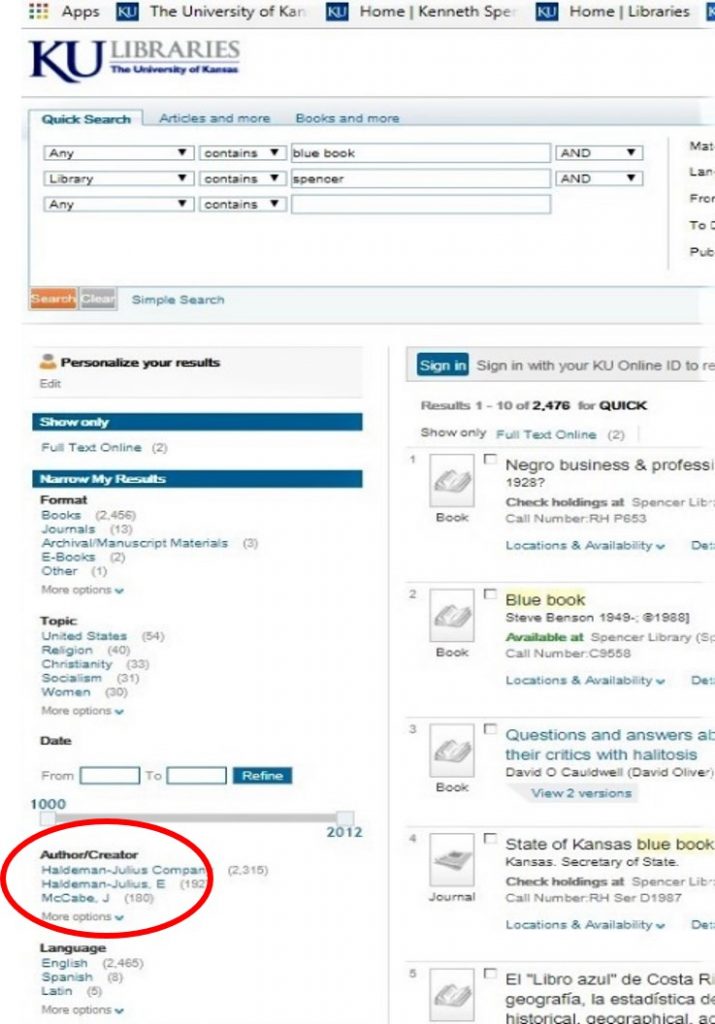

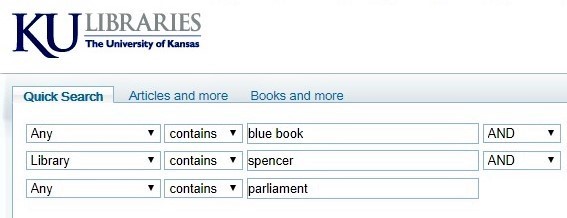

I started with a search online at the KU Libraries website. First, I clicked on the Advanced Search button below the Quick Search box because I wanted to limit my search to the Spencer Research Library.

Click image to enlarge.

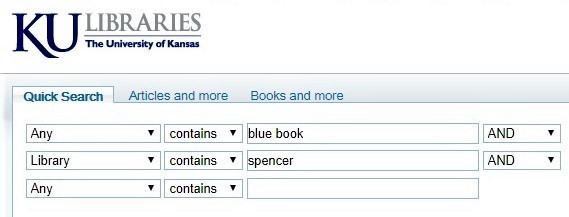

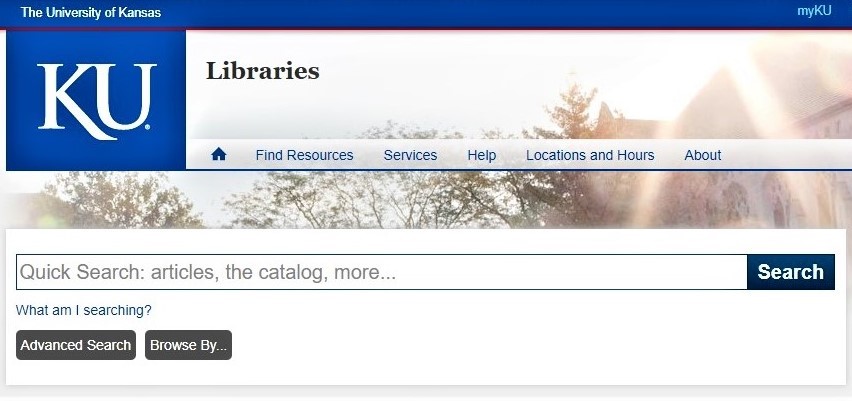

I typed in “blue book” (without quotation marks) in the first box to find items that contain those keywords. Next, I selected Library from the dropdown menu and typed in “Spencer” (without quotation marks) in the next box to limit the search to items showing Spencer Research Library as the location.

Click image to enlarge.

This led to 2,476 results. In a quick scan of my first few pages of search results, I did not immediately find irrelevant items, i.e., those that might contain the word blue and the word book somewhere in the catalog record but not together. (Note: selecting is exact from the dropdown menu instead of contains has the same effect as using quotation marks around the words blue book. The system searches for both words together as a phrase, bringing the search results down to 2,370 results.)

Definition 1: Official Publications and Authoritative Reports

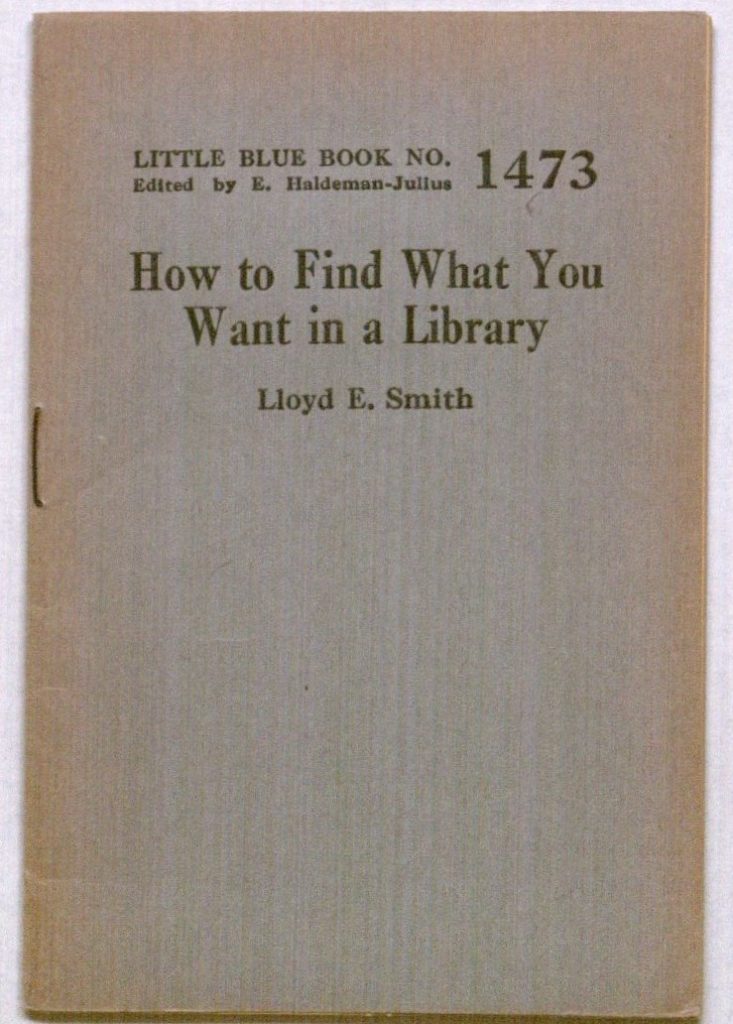

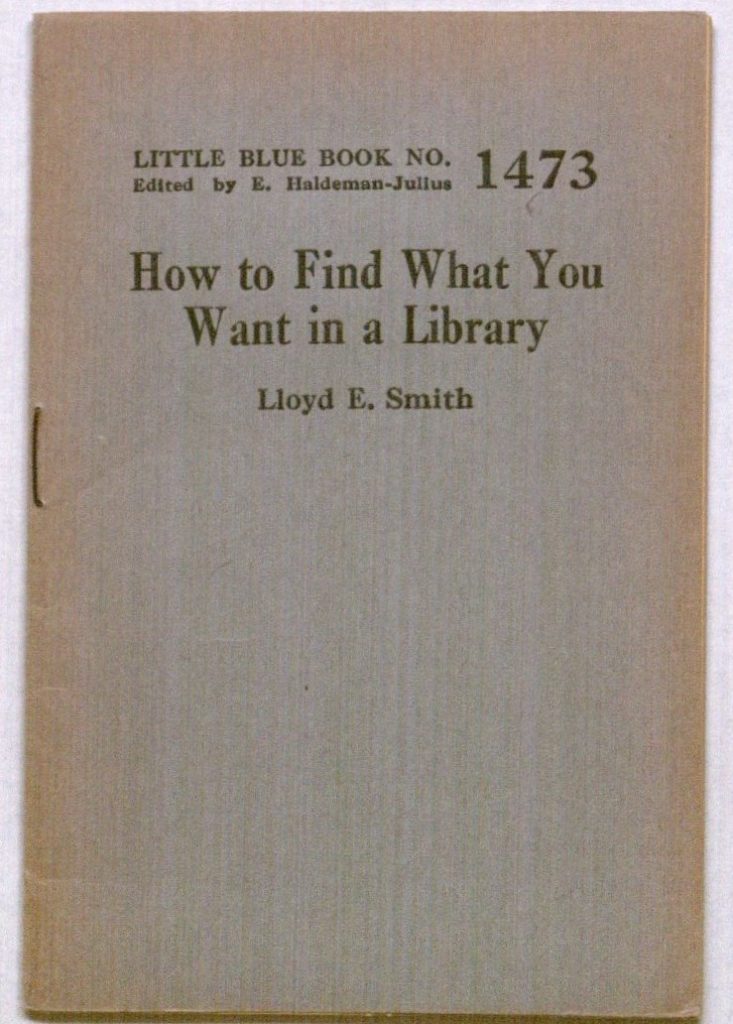

As I scanned through my search results, I looked for items that might be examples of official or authoritative publications. Several of the items in the list were from the Little Blue Book series published by the Haldeman-Julius Press from 1919 to 1951.

Cover of How to Find What You Want in a Library

by Lloyd E. Smith, 1929. Call Number: RH H-J 1473 Little.

You can learn more about Little Blue Books in

Spencer’s North Gallery exhibit. Click image to enlarge.

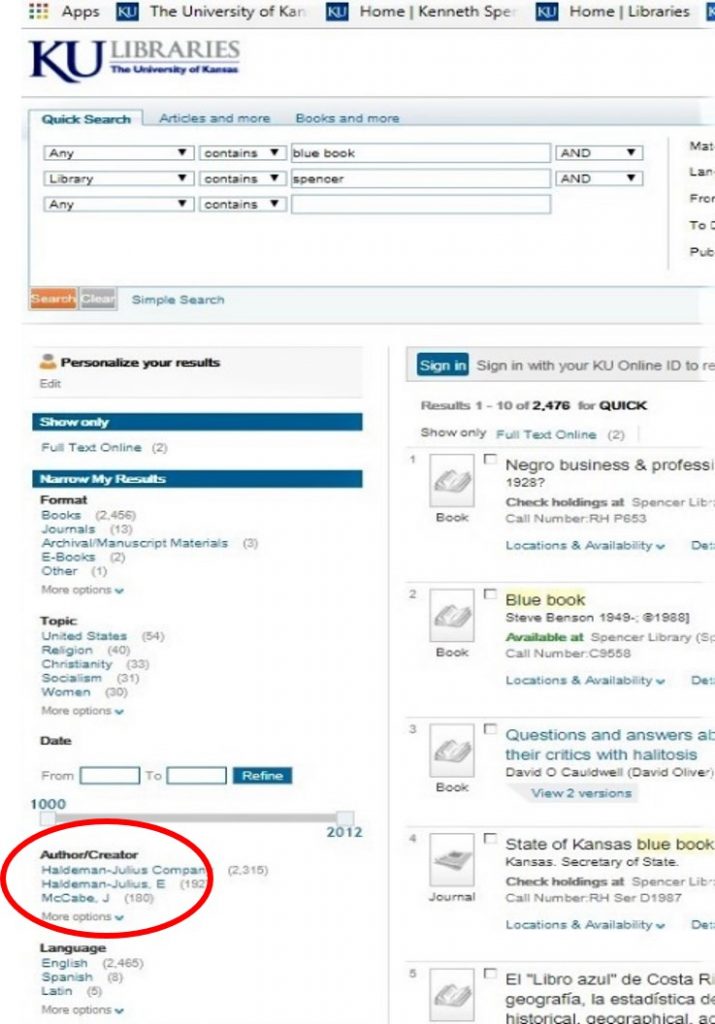

I decided to filter my search results to remove all or most of the Little Blue Books in order to identify more easily other types of blue books in the list. On the left side of KU Libraries’ page, next to the search results, I found the Narrow My Results heading. As shown in the screenshots below, I clicked on More options under Author/Creator. Then, I selected to “Exclude” the Haldeman-Julius Company and some of the authors who contributed to the Little Blue Book series. After I clicked on Continue, my search results were reduced to 159 items.

Click images to enlarge.

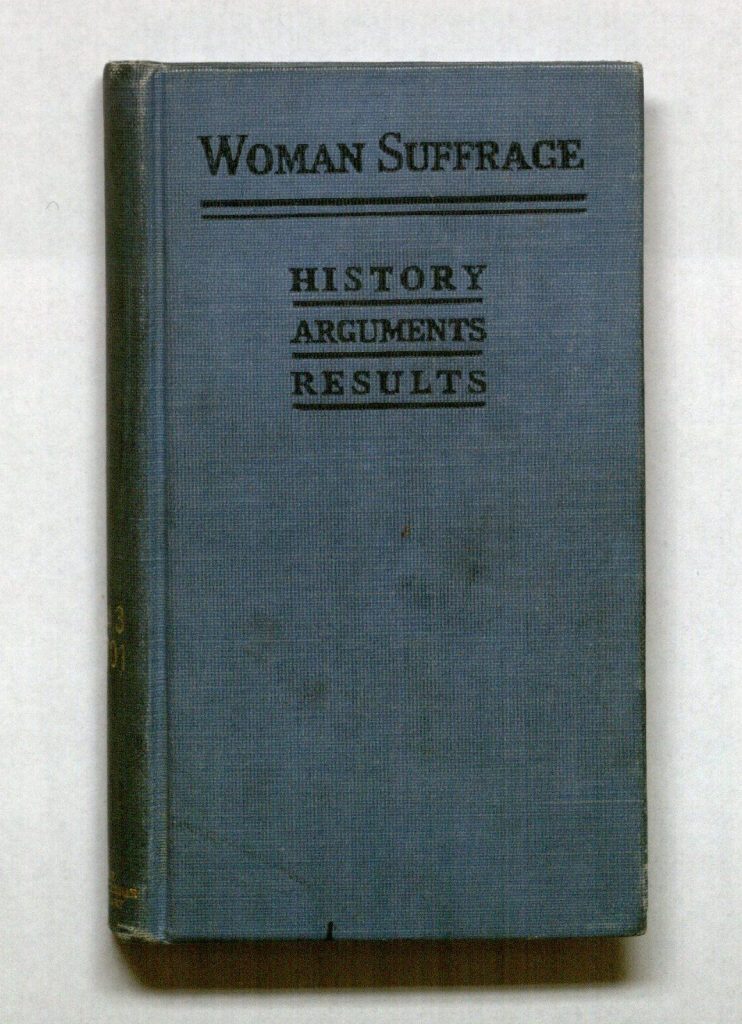

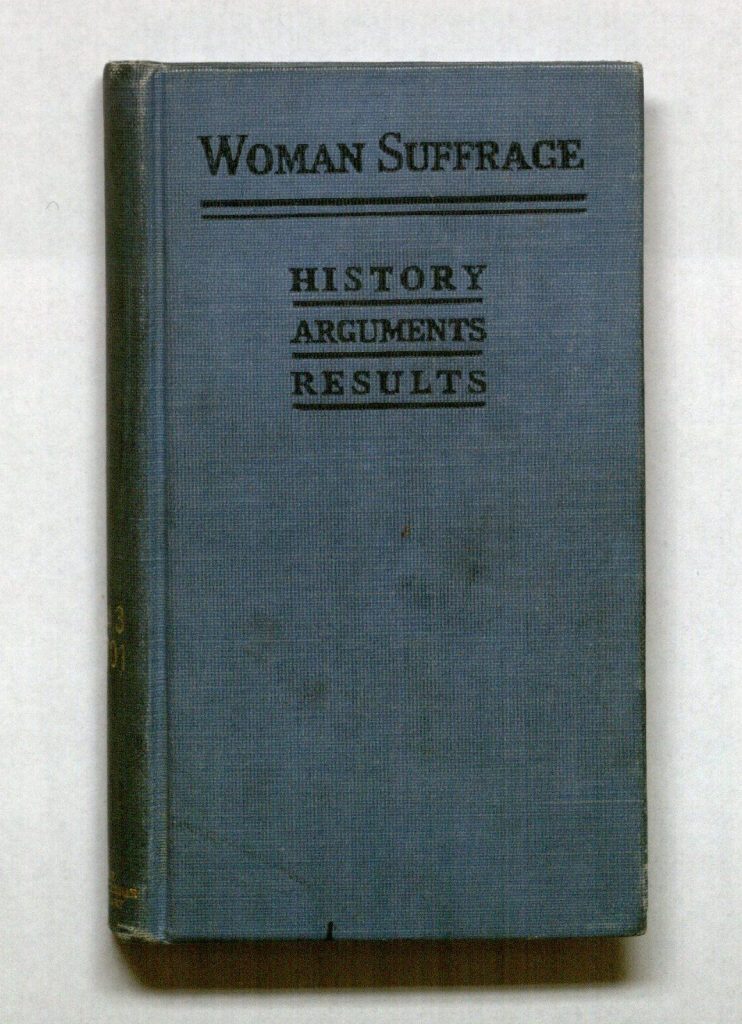

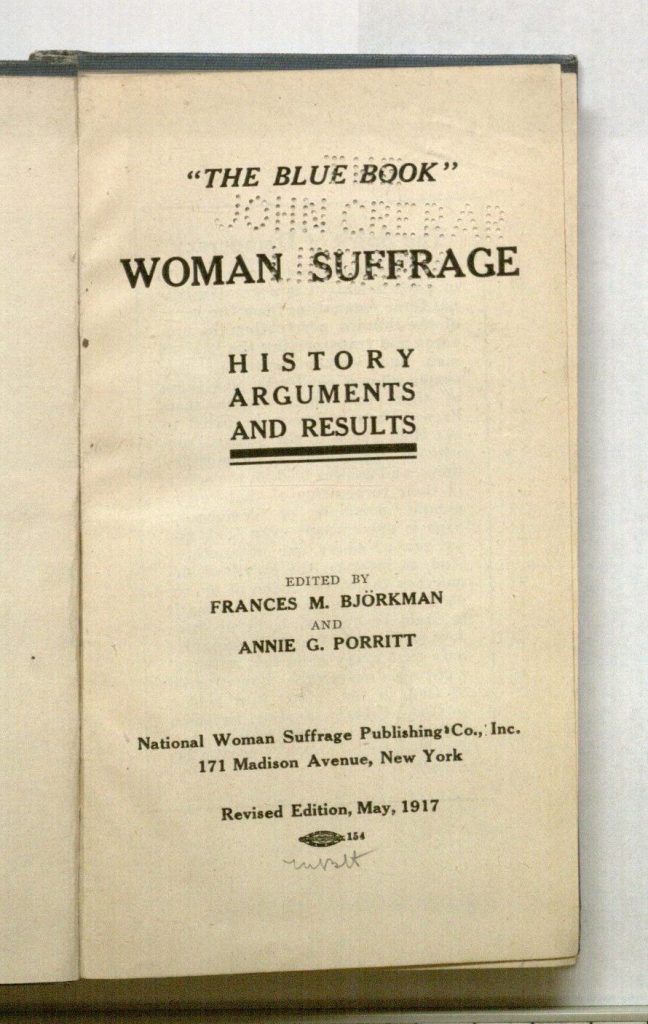

The example shown below is an additional authoritative or official blue book selected from my search results.

Cover (left) and title page (right) of “The Blue Book”; Woman Suffrage, History,

Arguments and Results, 1917. Call Number: Howey B2835. Click images to enlarge.

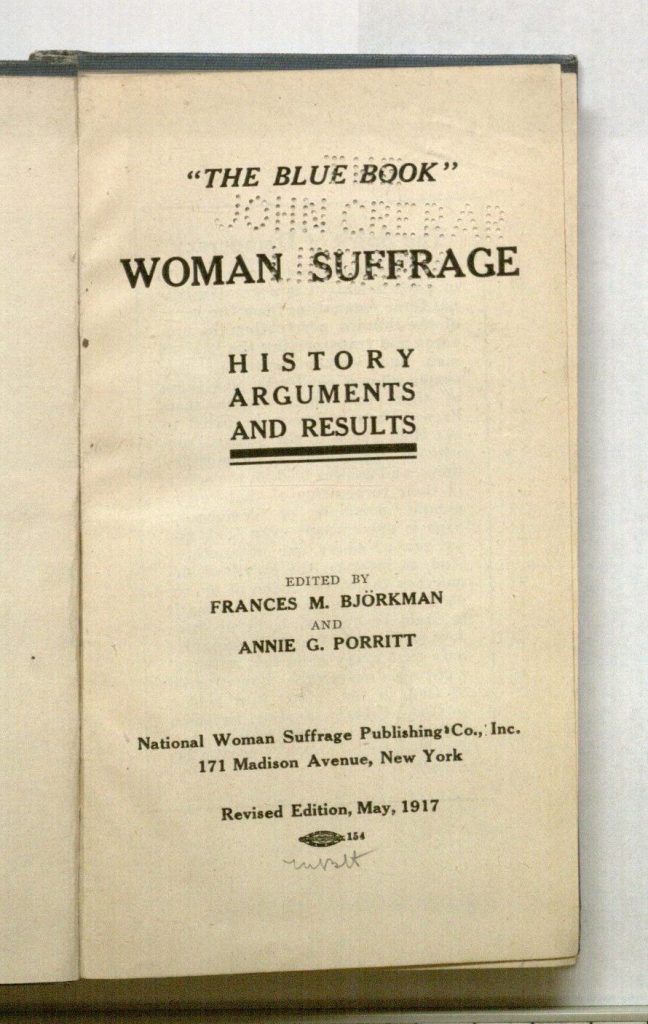

In an attempt to find a British parliamentary blue book, I went back to the top of the search results page and added the word parliament to my search terms.

Click image to enlarge.

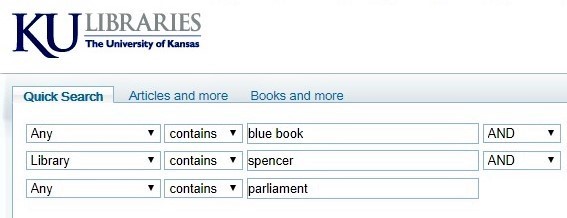

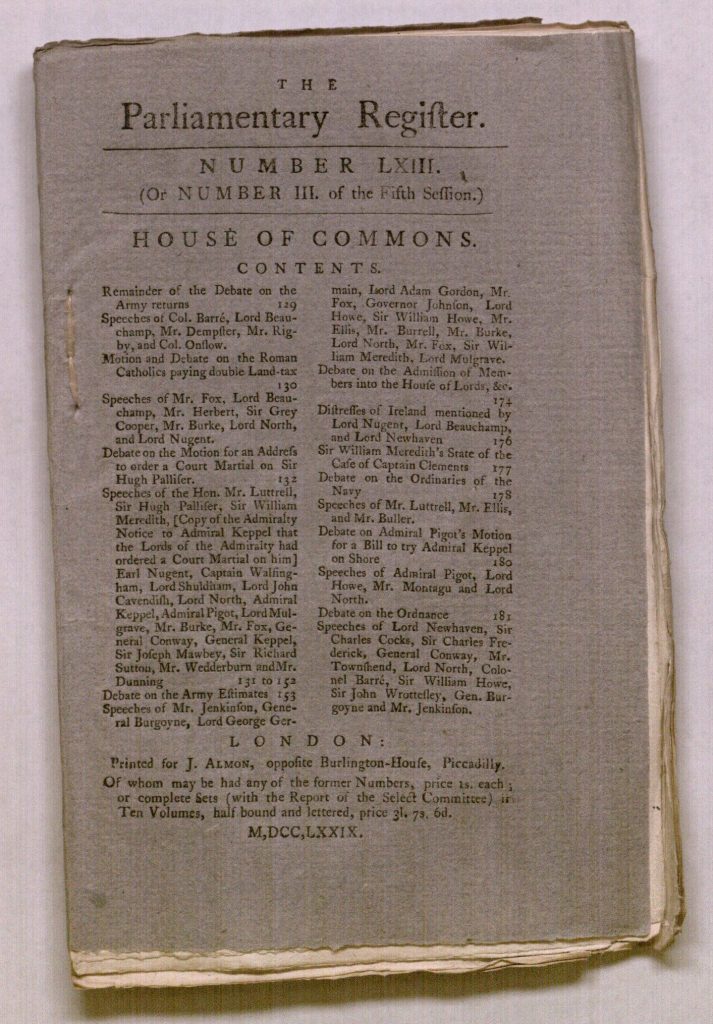

This resulted in four search results including The Parliamentary Register, an eighteenth-century history of the proceedings and debates of the House of Commons and the House of Lords, shown below.

Although it has faded, the cover of The Parliamentary Register (1779) is blue.

The KU Libraries catalog record explains that the volumes are “as issued,” i.e., “unopened,

in printed blue paper wrappers.” See in the image above how the pages

have not been cut open at the top. Call Number: Bond C291.

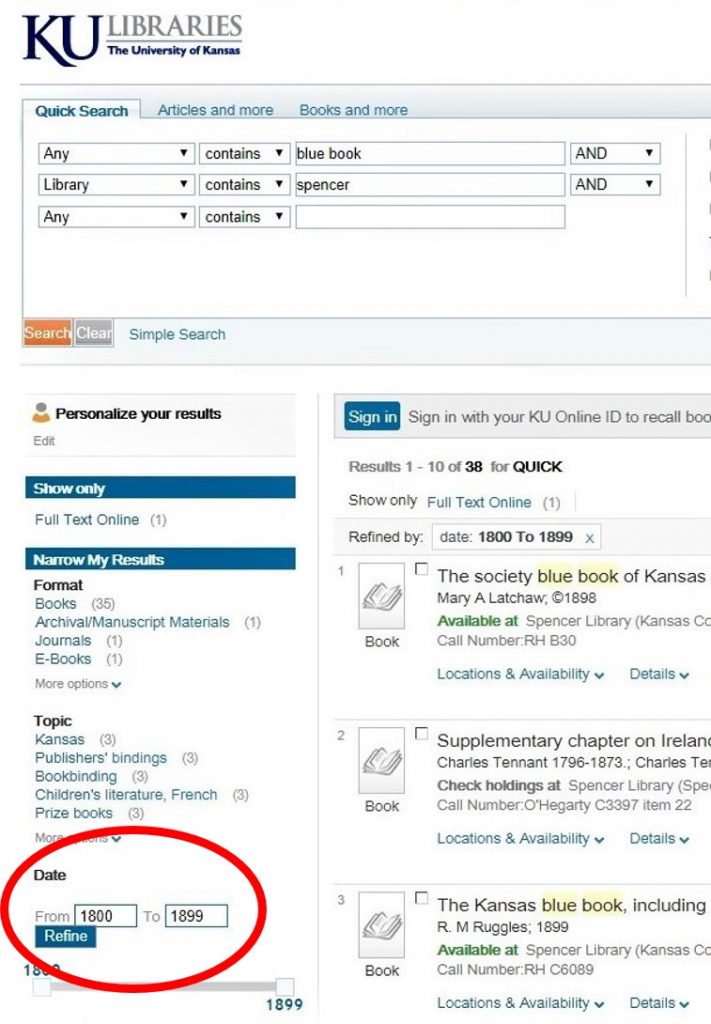

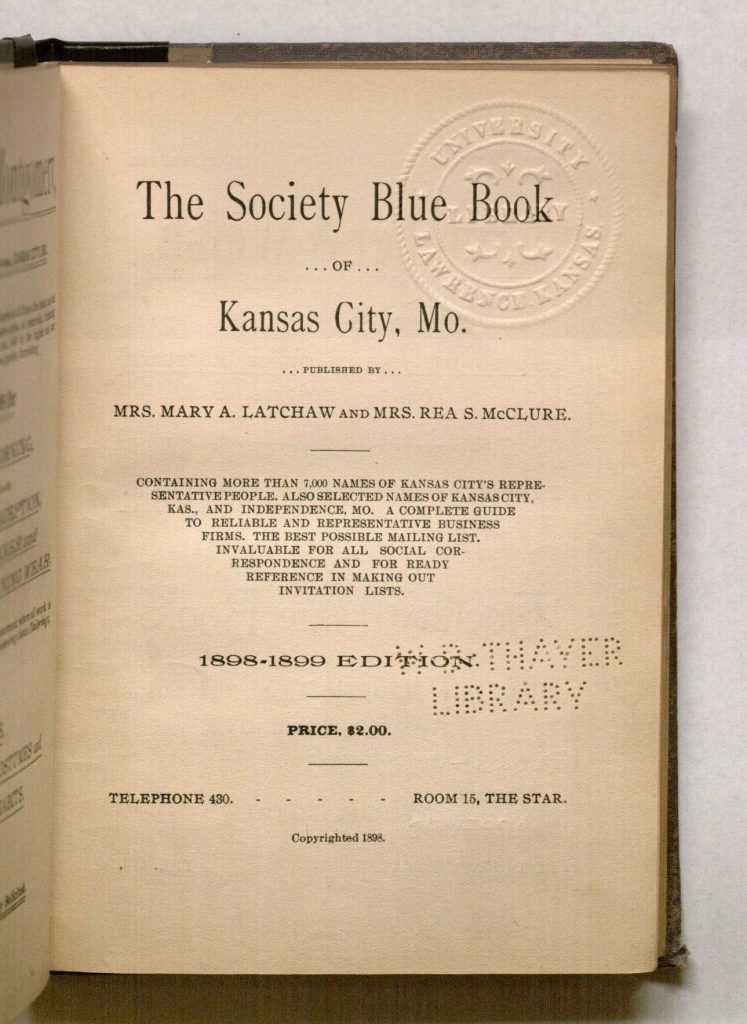

Definition 2a: Directory of Persons of Social Prominence

Having found examples of blue books from the 18th and 20th centuries, I hoped to find a social register from the 19th century. I went back to my list of 159 search results and narrowed my results again, this time by date. I typed in a date range of 1800 to 1899.

Click image to enlarge.

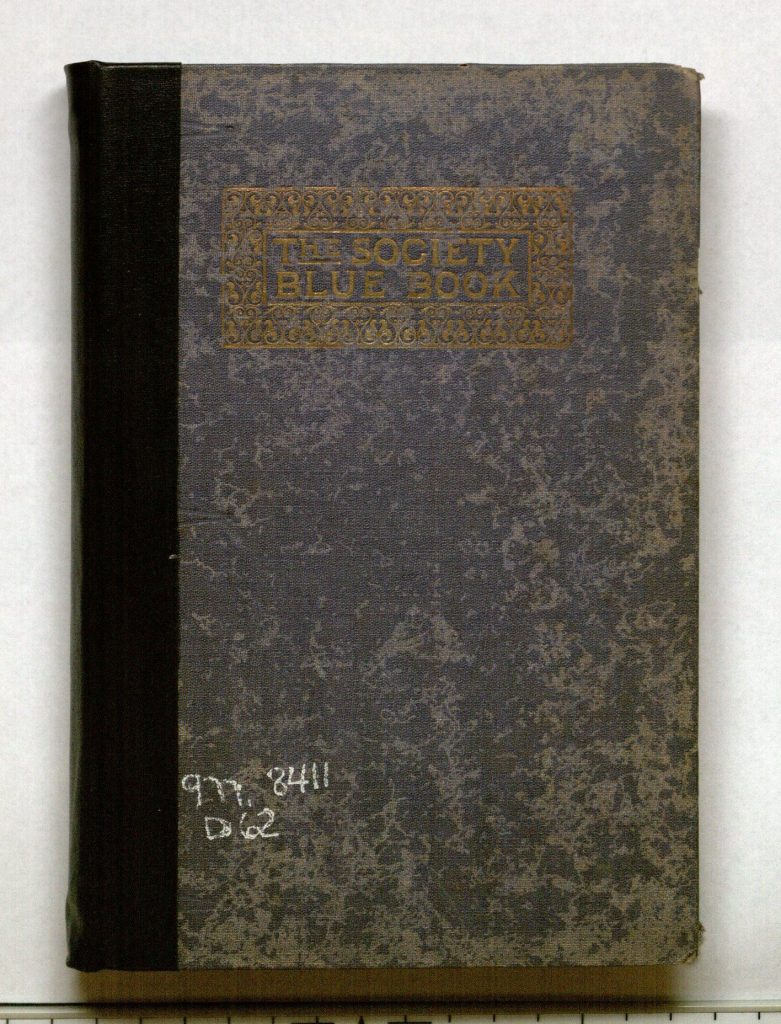

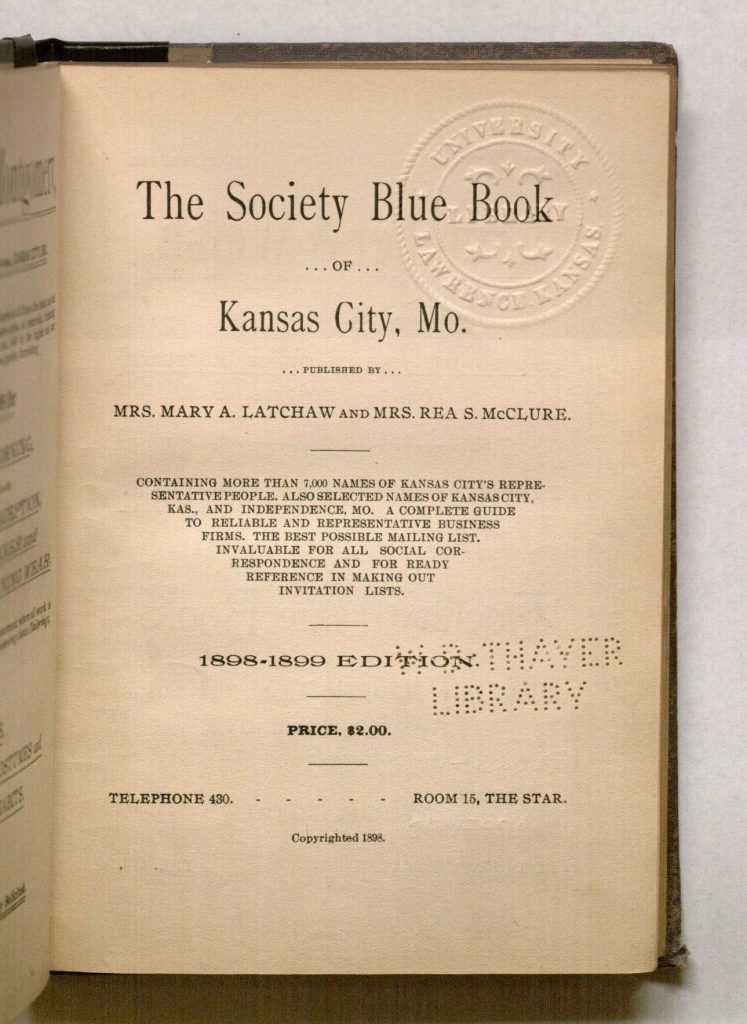

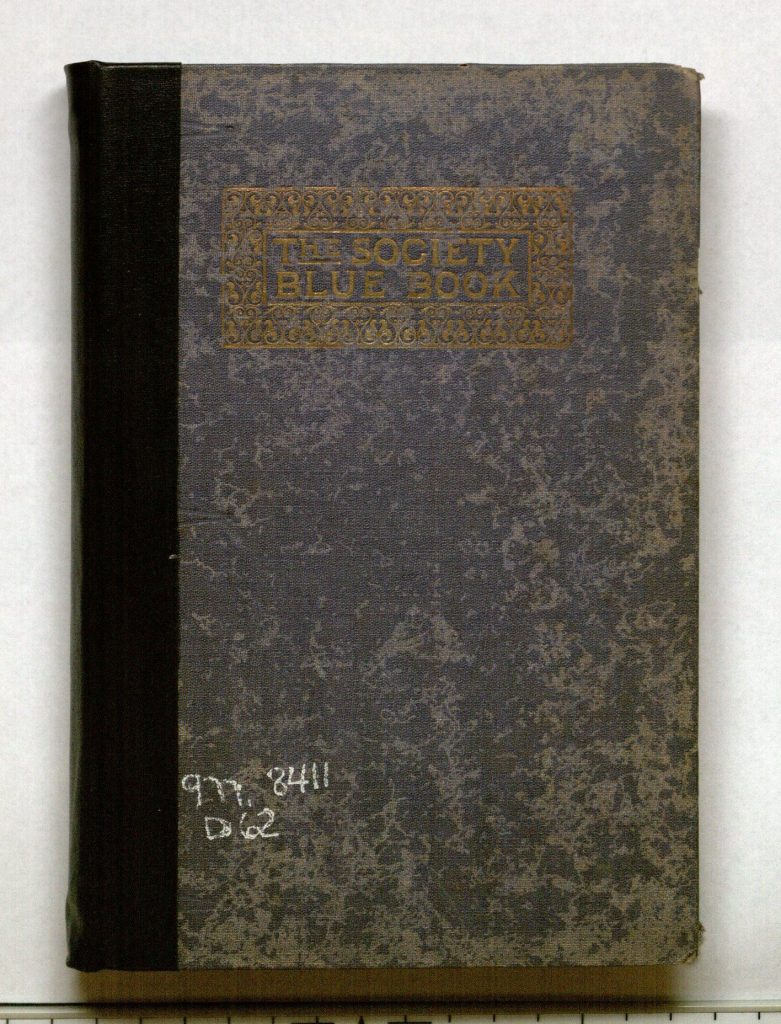

I found the blue book shown below which was published in 1898.

The Society Blue Book of Kansas City, Mo., 1898. Call Number: RH B30. Click image to enlarge.

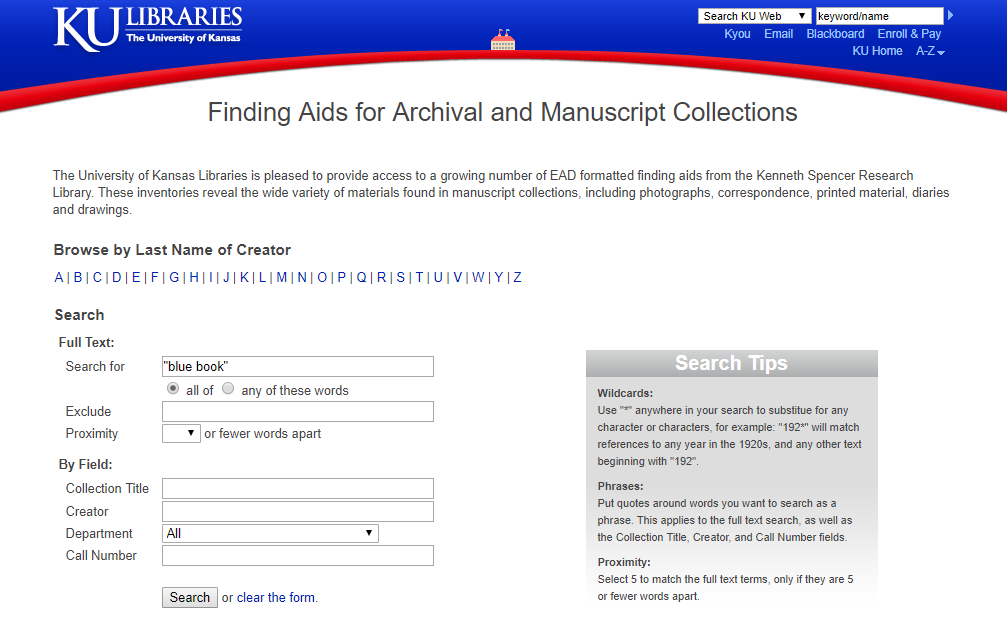

Definition 2b: Booklet for Exams

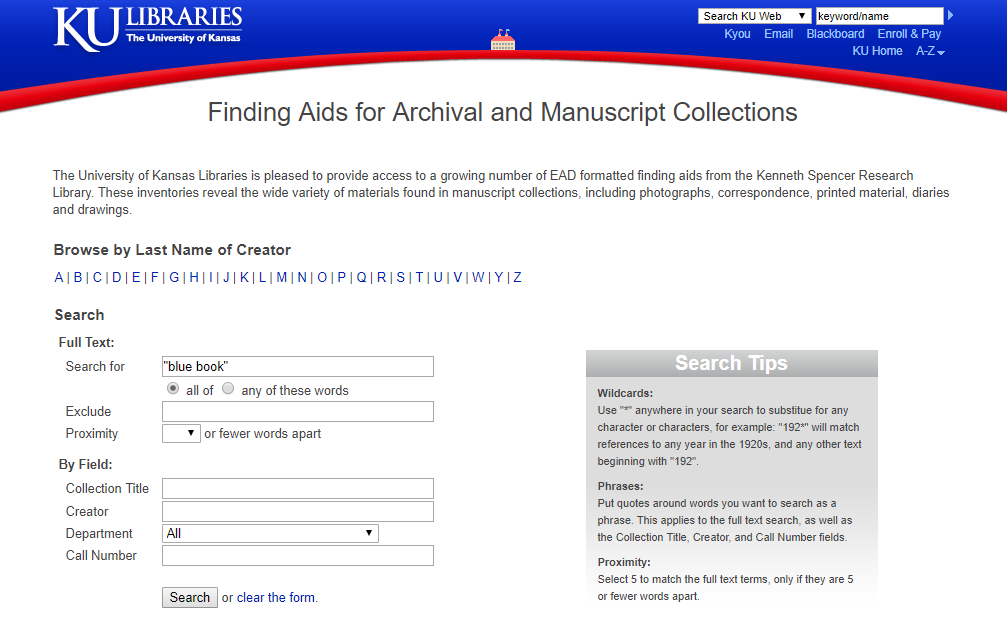

I determined that a good place to look for an example of a blue book used for a college exam would be in a collection of unpublished, personal papers. I started my search online using the search interface for finding aids on the Spencer website. I typed “blue book” (with quotation marks to search for both words together as a phrase) into the Search for field. I retrieved nineteen results.

Click image to enlarge.

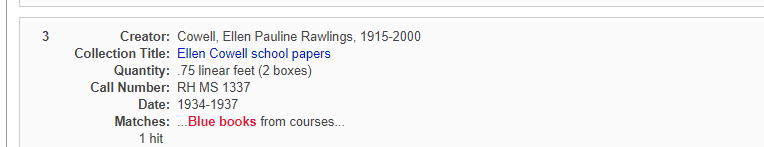

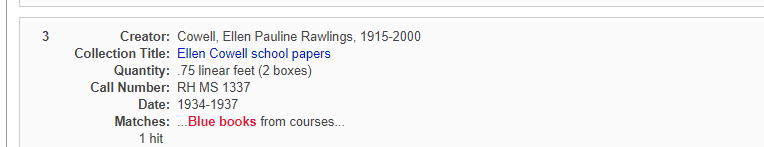

The third item in the results list seemed to be the type of blue book I was hoping to find.

Click image to enlarge.

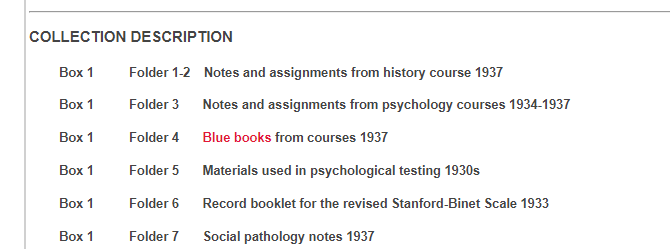

I clicked on this item and viewed the finding aid which further confirmed that the blue book was from course work in 1937 and identified in which box and folder I would find it.

Click image to enlarge.

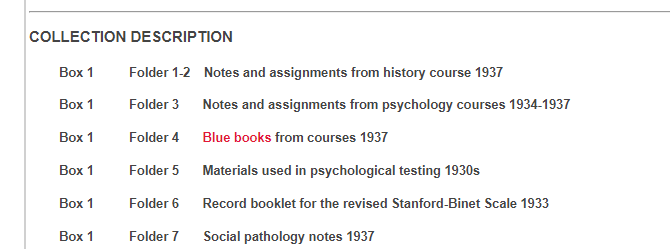

The exam blue book is shown below.

Cover of Pauline Rawlings’s blue examination book, 1937.

Ellen Cowell School Papers. Call Number: RH MS 1337.

Click image to enlarge.

Definition 3: Automobile Guide

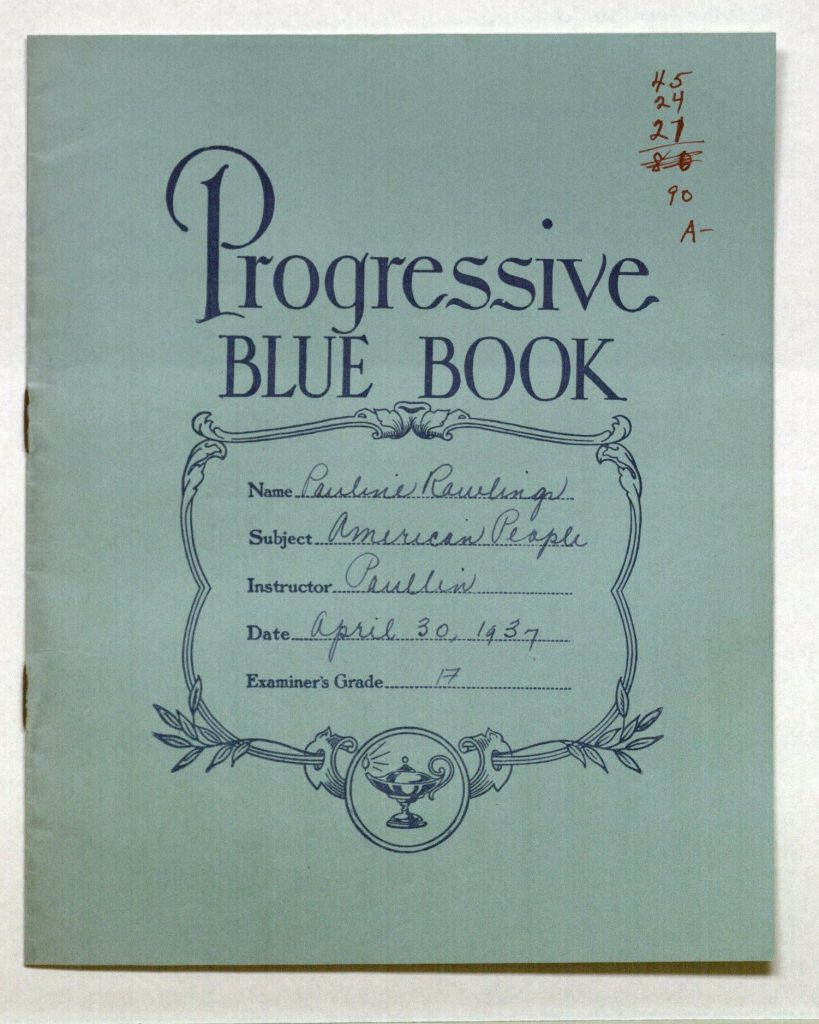

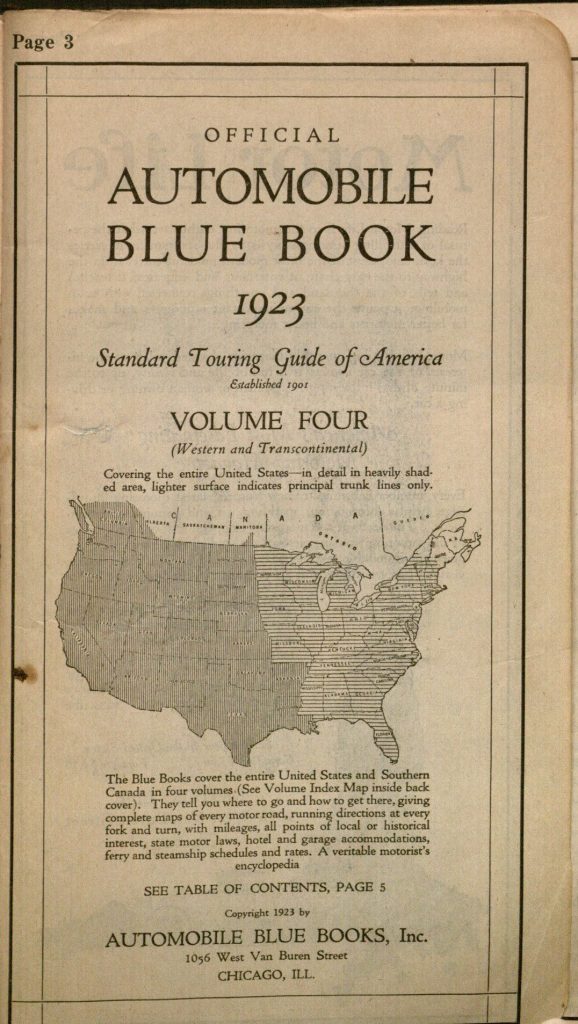

Going back to the KU Libraries’ search results list of 159 items, I was able to locate a fascinating example of an automobile blue book, The Official Automobile Blue Book 1923, shown below.

Title page of the Official Automobile Blue Book, Volume 4, 1923.

At the time, not all roads were paved or marked.

Getting from one city to another sometimes meant paying close attention

to the mileage from one turn or fork in the road to the next.

Call Number: C11263. Click image to enlarge.

My search process was a success! In the Spencer Research Library collections, I was able to locate examples of each type of blue book that is described in the dictionary definition. Often, research leads to more questions. I found myself wondering about the choice of blue paper for the covers of the British parliamentary publications. Why blue? Sounds like a great topic for a new search and another blog post!

Stacey Wiens

Reference Specialist

Public Services