Banned Books Week: Redacted for the Inquisition

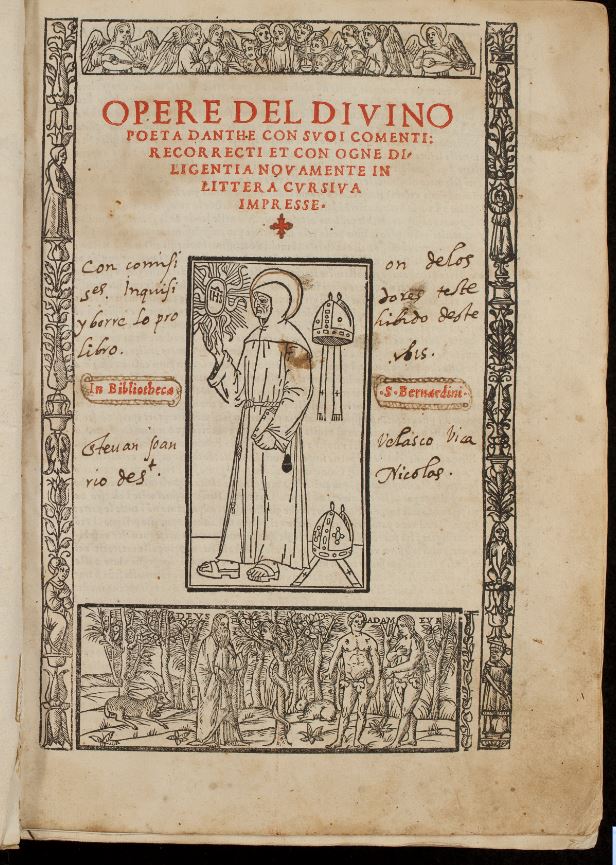

September 28th, 2017September 24-30 is Banned Books Week, an annual event in which libraries and readers celebrate the freedom to read. With this in mind, today we feature several images from an early printed copy of The Divine Comedy by the medieval Italian poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). The copy in question is from a 1512 edition printed by Bernadino Stagnino in Venice, a city that served as a vibrant center for early printing and the book trade. Stagnino’s edition combines a recently re-edited version of Dante’s text (1502) with an earlier commentary on the poem by the 15th century humanist scholar Cristoforo Landino.

But wait, you ask, what does this have to do with censorship? Sometime in the decades following its printing, Spencer’s copy traveled from Venice to Spain, and in the late 1500s fell under the review of the Inquisition and Catholic clerics concerned with religious orthodoxy and the spread of heretical ideas. A manuscript notation in Spanish on the volume’s title page reads: “Con comisión de los S[eñor]es Inquisidores teste y borre lo prohibido deste libro” (“With commission from the Señores Inquisitors cross out and erase what is prohibited in this book”) followed by the name [E]stevan Joan Velasco Vicario de S[an]t Nicolás (Esteban Juan Velasco, vicar of San Nicolás).*

“…cross out and erase what is prohibited in this book”: the title page, with notations in Spanish, of Spencer’s copy of Opere del die vino poeta Danthe [Divina Commedia]. Venice: Bernardino Stagnino, 1512. Call #: Summerfield C1189. Click image to enlarge.

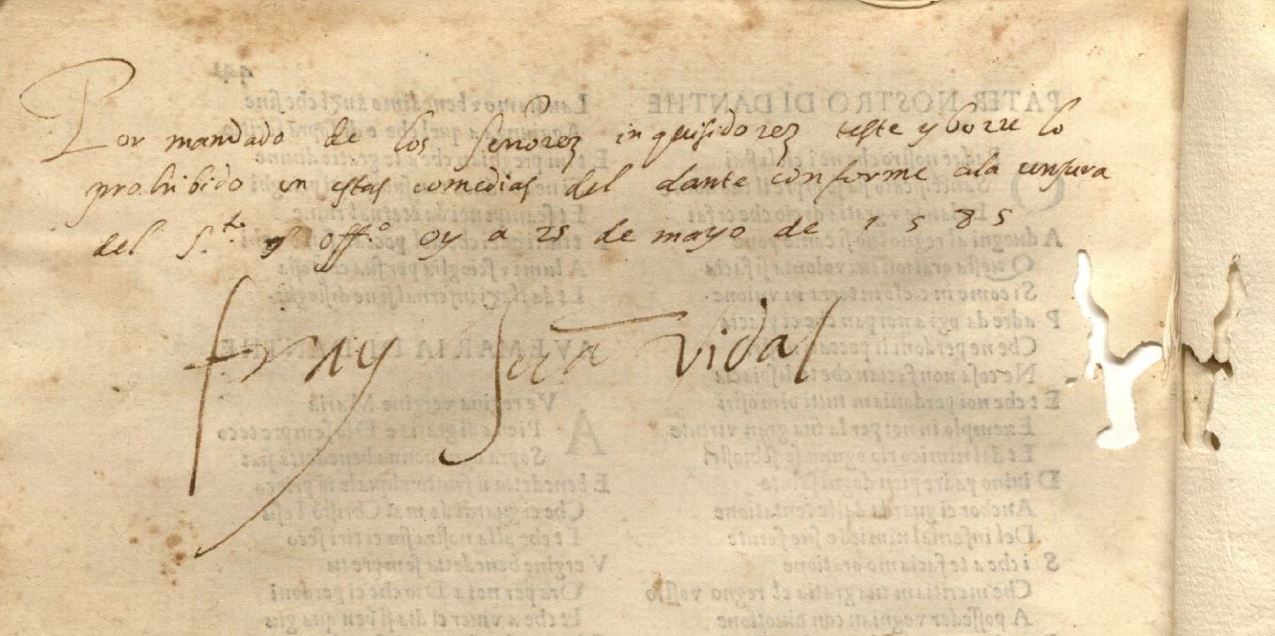

A similar notation by a different cleric appears on the verso of the volume’s final page of text: “Por lo mandado de los señores inquisidores teste y borre lo prohibido en estas comedias del dante conforme a la censura del Sto Off[ci]o [h]oy a 25 de mayo de 1585. Fray Juan Vidal” (By the order of the señores inquisitors cross out and erase what is prohibited in these comedies of Dante according to the censure of the Holy Office today, 25 May 1585 Fray Juan Vidal).*

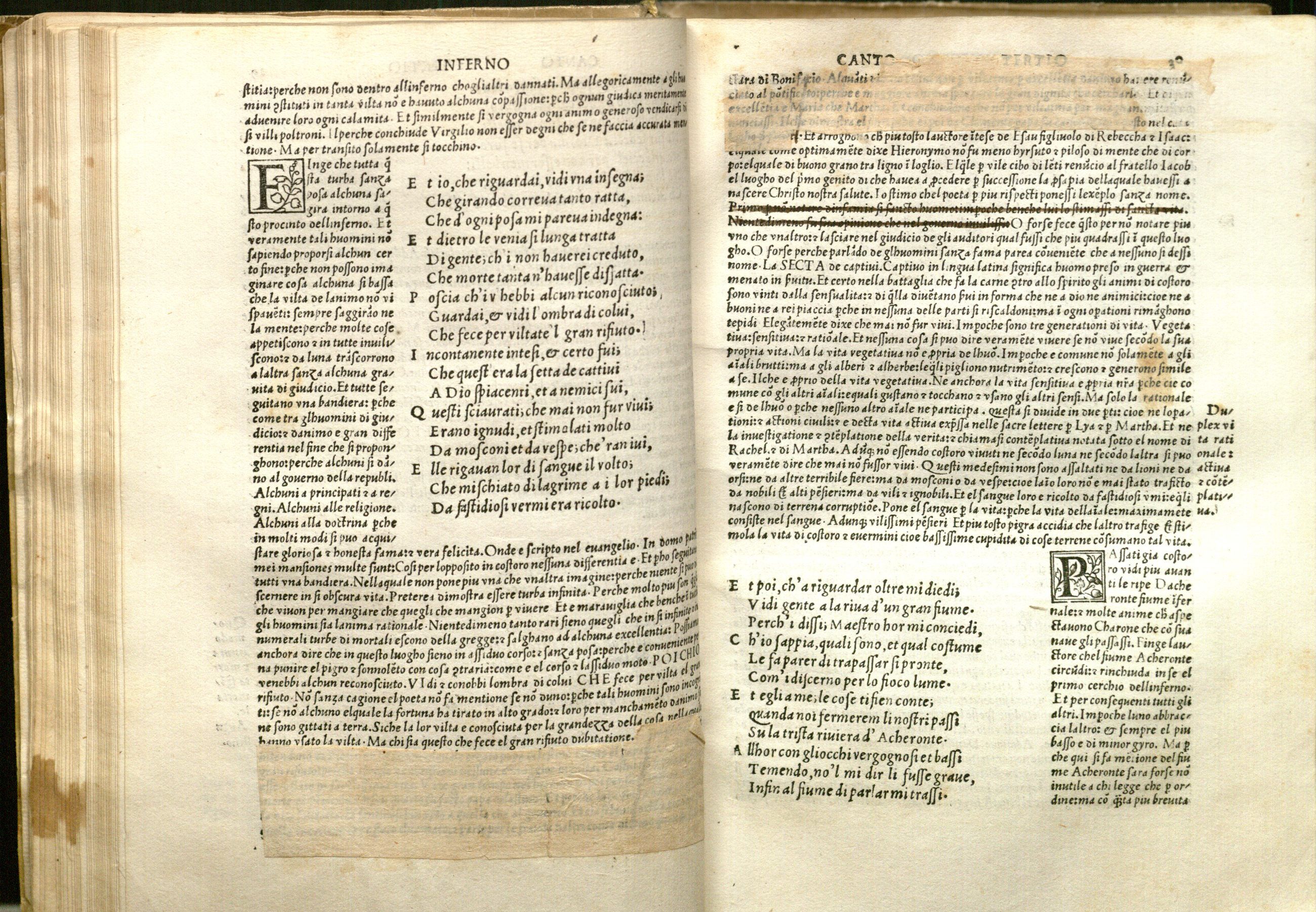

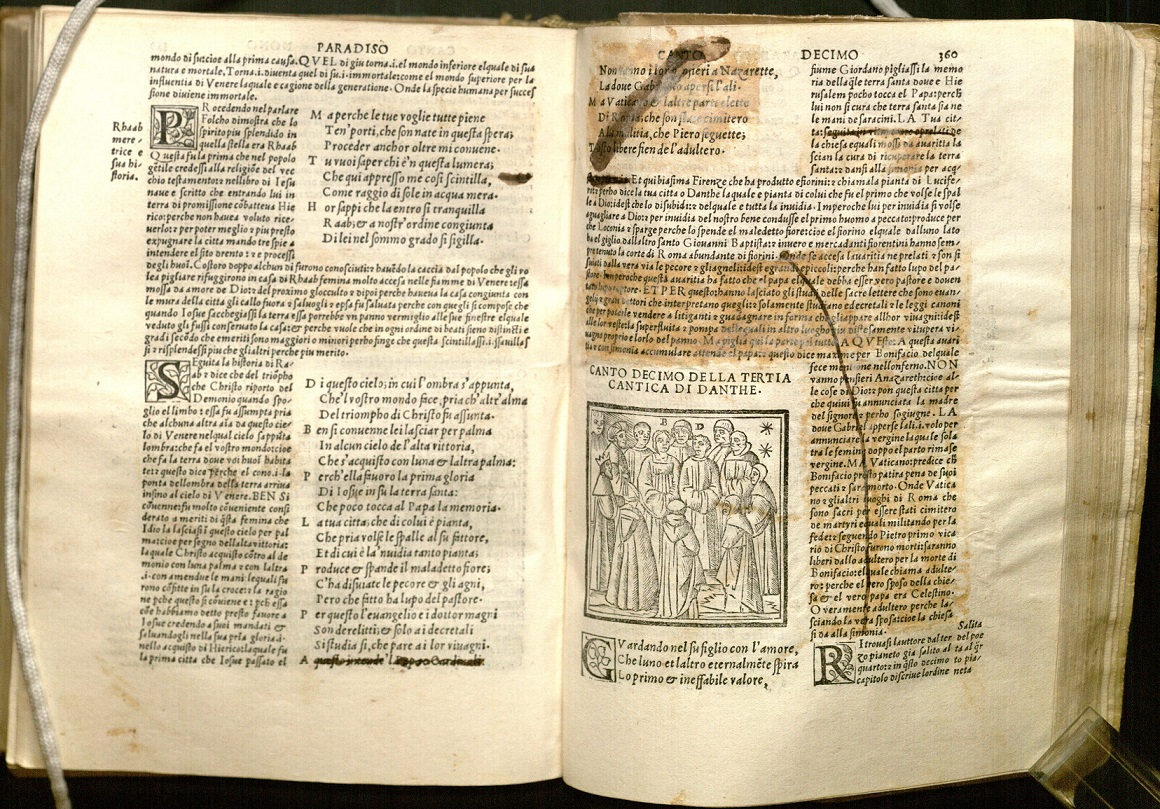

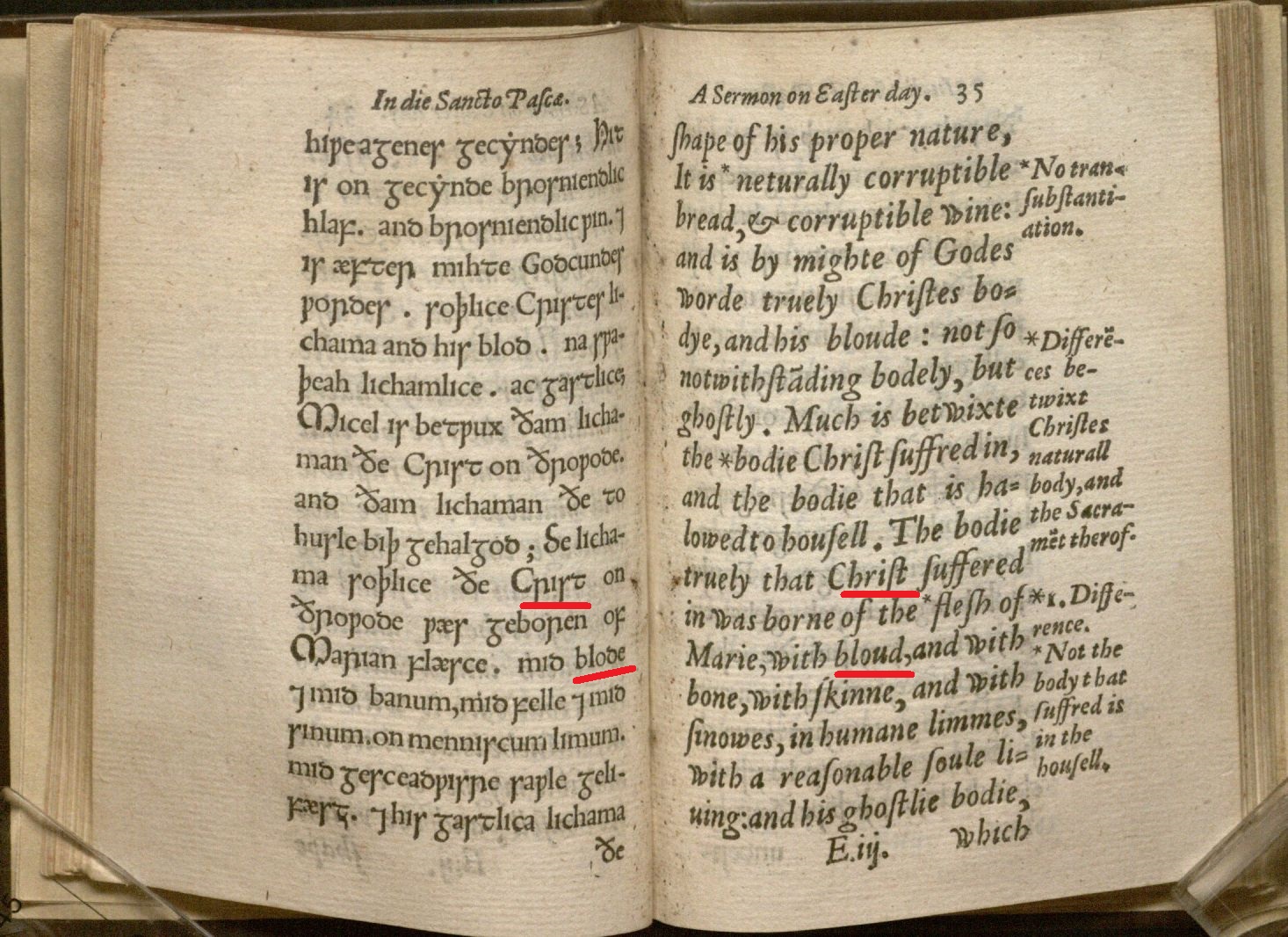

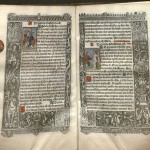

In paging through the volume, readers will find several redacted passages of varying lengths. Landino’s commentary receives the most expurgation, though lines from Dante’s poem are redacted on occasion as well. In some places, an offending line is simply crossed out in ink, while longer passages have been papered over so as to render them illegible. Once the prohibited passages had been redacted, the volume could be retained and consulted.

Passages in Landino’s commentary that have been redacted by the addition of blank paper slips and by crossing out lines of text in ink.

A later reader appears to have succeeded in removing much of the paper that once covered some of the offending passages. Although some discoloration remains from the glue used to affix the paper slips, the text is now visible. You can also see the censor’s original ink dash, marking the portions of text to be redacted or pasted over.

Text restored?: the yellowy-brown patches indicate sections where paper slips were once glued to cover over passages judged offensive. Some remnants of the paper are visible above in the block of text at the bottom left (click image to enlarge). Dante Alighieri. Opere del die vino poeta Danthe [Divina Commedia]. Venice: Bernardino Stagnino, 1512. Call #: Summerfield C1189.

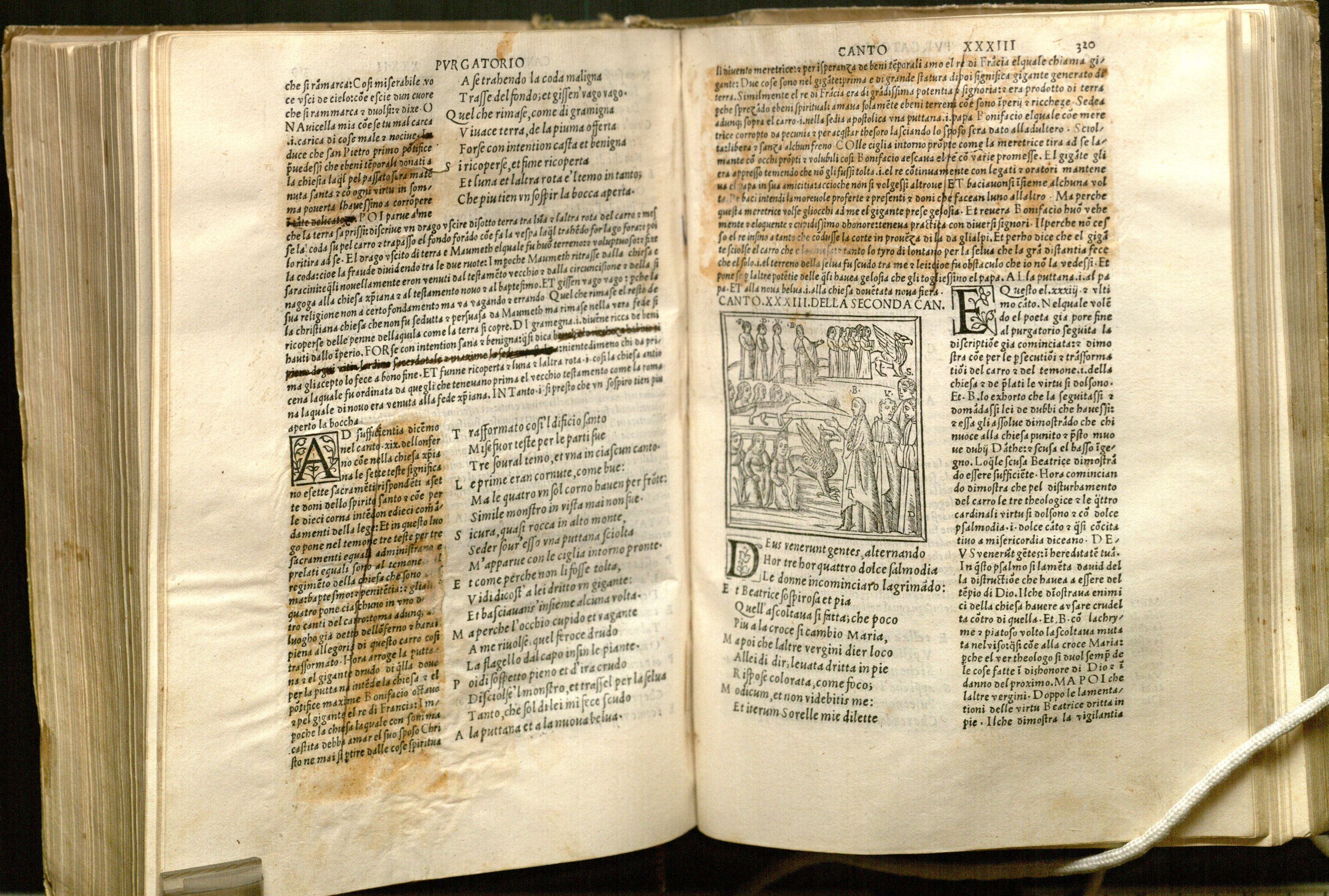

As readers of Dante know, The Divine Comedy is divided into three sections or “canticles,” one for each of the three realms of the afterlife visited by the character of Dante over the course of the poem: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso (Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise). As one might expect, most of the redacted passages appear in the Inferno. (It can be controversial to put historical personages, including Church leaders, in Hell, and to discuss the political and theological matters that result in damnation.) However, Spencer’s copy also contains at least one censored passage in both the text and commentary of the Purgatorio and Paradiso as well.

Trouble in Paradise: expurgated passages in Dante’s verse and Landino’s commentary toward the end of Canto IX in the “Paradiso” section of The Divine Comedy (click image to enlarge). Dante Alighieri. Opere del die vino poeta Danthe [Divina Commedia]. Venice: Bernardino Stagnino, 1512. Call #: Summerfield C1189. This passage, which critiques the Vatican and Church leaders, is also redacted in a copy of a 1564 edition of Dante’s work (with commentaries) held at Brandeis University.

Spencer’s expurgated copy of the Dante’s Divine Comedy offers a fascinating material example of censorship in early modern Spain. If this brief post has whet your appetite for exploring this subject further, consider visiting He who destroyes a good booke, kills reason it selfe, an online re-issue of a notable 1955 KU Libraries exhibition catalogue on intellectual freedom. The catalogue’s section on Spain contains examples of other volumes from the library’s collections that were censored under the Inquisition, including a book on proverbs by Juan de Aranda that has been redacted with ornamented slips.

Curious about more contemporary instances of censorship and challenges to books? Take a look at the list of the top ten most challenged books of 2016, as compiled by the American Library Association Office for Intellectual Freedom. Or, if you live in Lawrence, consider visiting the Lawrence Public Library, which will be distributing a different card in its 2017 Banned Books Trading Card series each day this week.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian

*Transcriptions and translations courtesy of Professor Luis Corteguera, with additional insight from Professors Patricia Manning and Isidro Rivera.

Click on the thumbnails below for images of additional redacted passages in Spencer’s 1512 edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy with commentary by Cristoforo Landino.