Collection Snapshot(s): Victorian Fashion Edition

November 4th, 2014One of the wonderful things about class visits is that they often send you hunting through the far reaches of the library’s collections in search of interesting and relevant holdings. A recent visit from ENGL 572: Women and Literature: Women in Victorian England led me to happen upon two very rare Victorian fashion periodicals among Spencer’s collections. These British weeklies offered up the latest styles (hint: full skirts are in) alongside commentaries and entertainments that the editors thought might interest their nineteenth-century female readership.

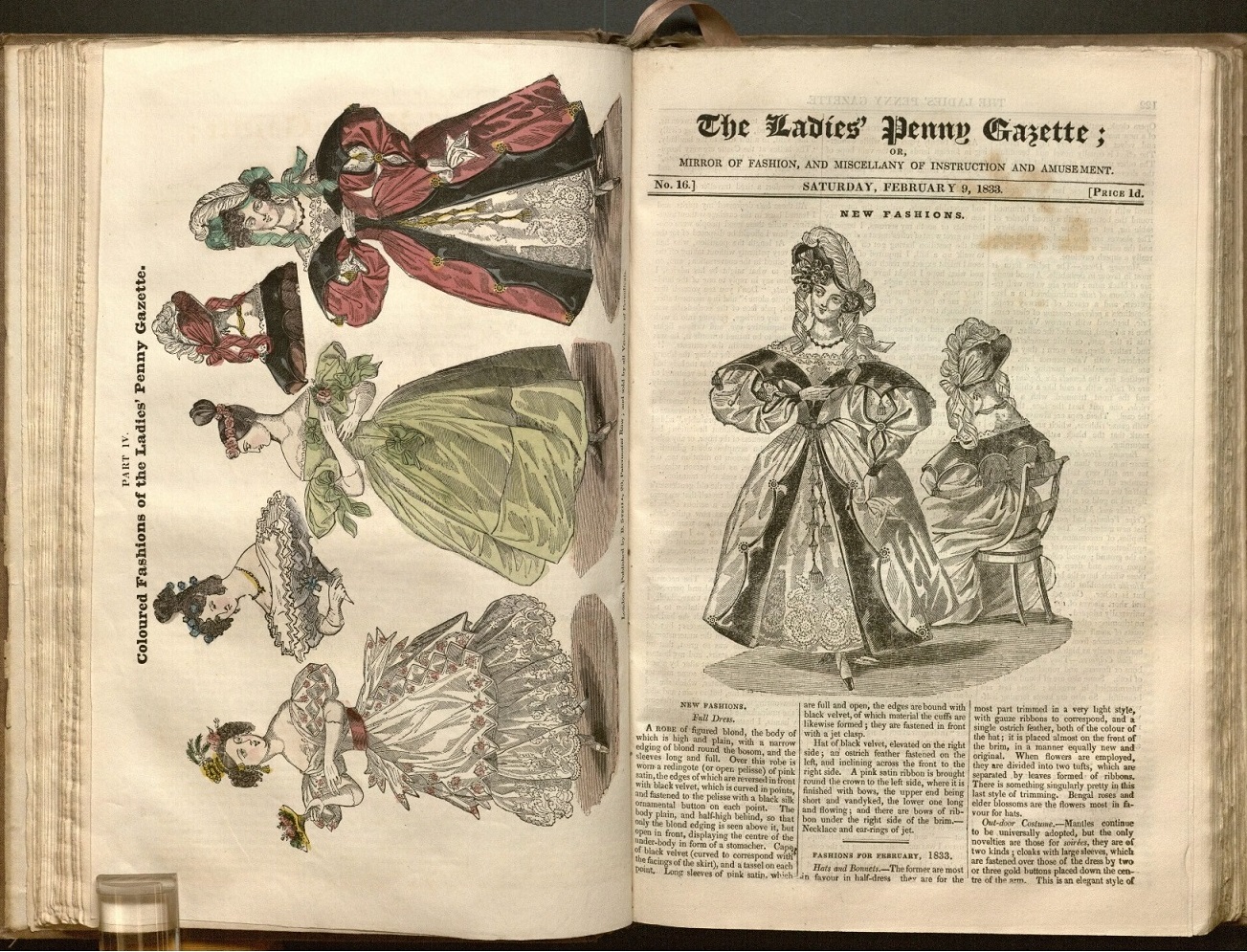

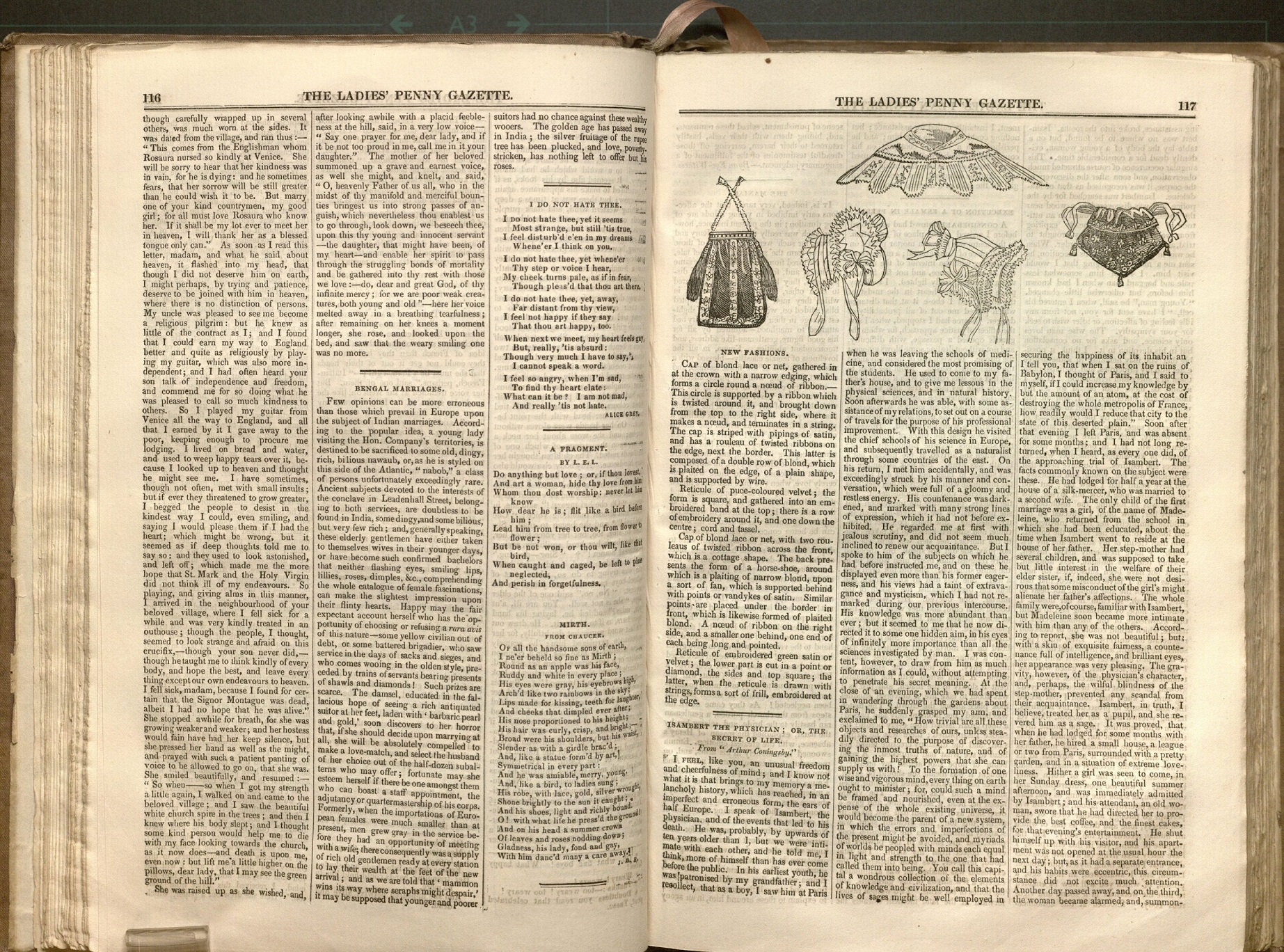

The Ladies’ Penny Gazette (published 1832-1834) dates from the period just before Queen Victoria’s ascent to the throne in 1837. Subtitled the Mirror of Fashion, and Miscellany of Instruction and Amusement, this weekly combined fashion with articles on subjects of interest to women, theater reviews, sheet music, and literary pieces. Subscribers were treated each month to a bonus sheet of “Coloured Fashions of the Lady’s Penny Gazette,” in which the dresses were hand-colored, even if somewhat hastily so. For those interested in literature, the Gazette offers some finds as well. Next to a discussion of lace and caps on one side and an article on “Bengal Marriages” on the other is “A Fragment” by the poet L. E. L. (Letitia Elizabeth Landon).

Top and middle: the “Coloured Fashions” supplements and first pages of issues No. 16 (1833 February 9) and No. 33 (1833 June 8) of The Ladies’ Penny Gazette; or, Mirror of Fashion, and Miscellany of Instruction and Amusement. Call #: D4551. Bottom: an opening from issue No. 15 (1833 February 2) featuring L.E.L’s poem “A Fragment.” Click images to enlarge.

Though brief by modern standards–at a lean eight pages an issue–The Ladies’ Penny Gazette made the most of its allotted space, presenting pithy, sometimes biting, commentary between its longer pieces. One such quip, titled “Small Talk,” gives a sense of how the magazine’s conceptions of womanhood are more complicated than a label like “Victorian fashion magazine” might immediately suggest:

Small Talk — Small talk is administered to women as porridge and potatoes are to peasants–not because they can’t discuss better food, but because no better is allowed them to discuss. (No. 42, August 10, 1833, page 30)

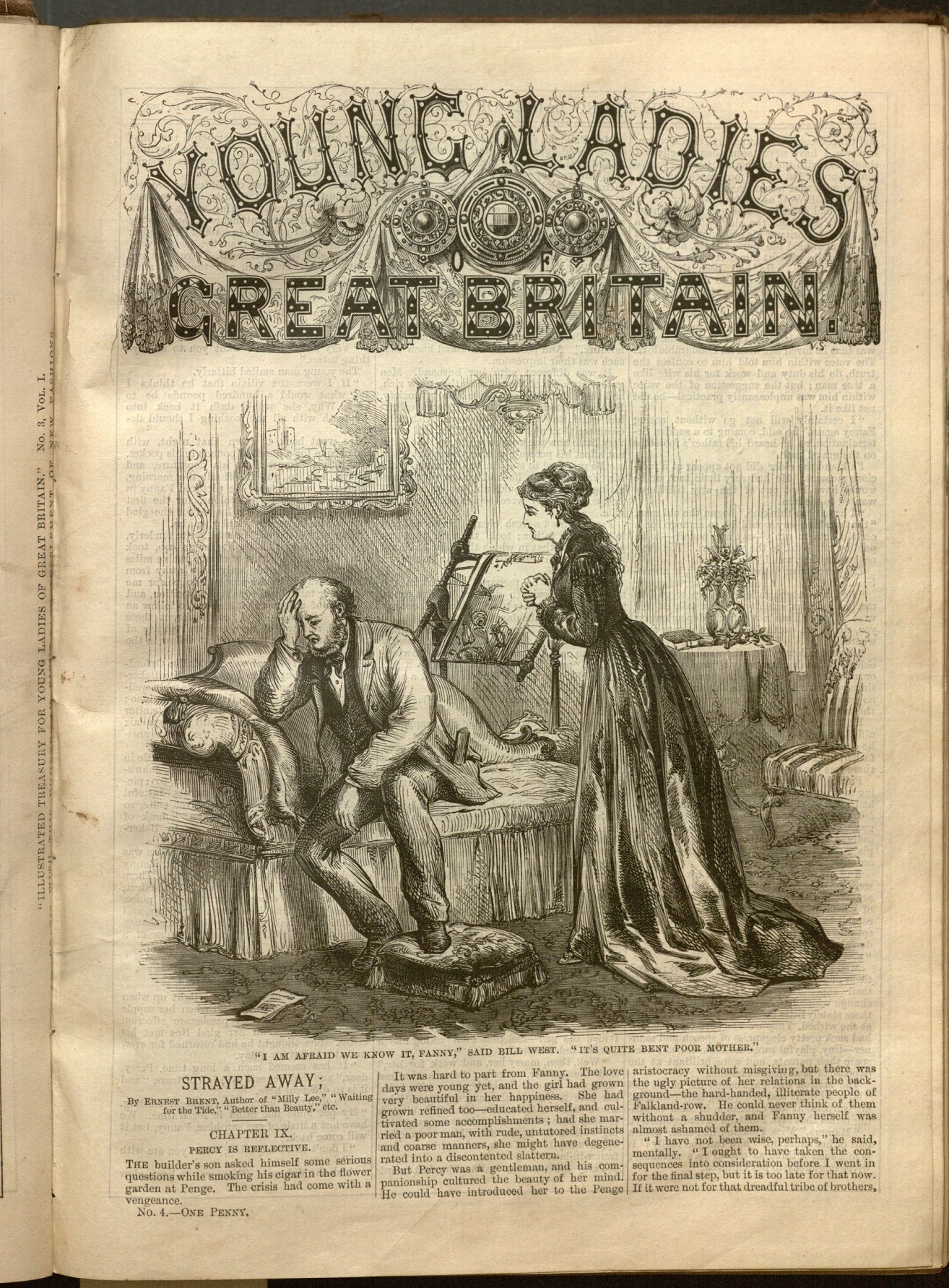

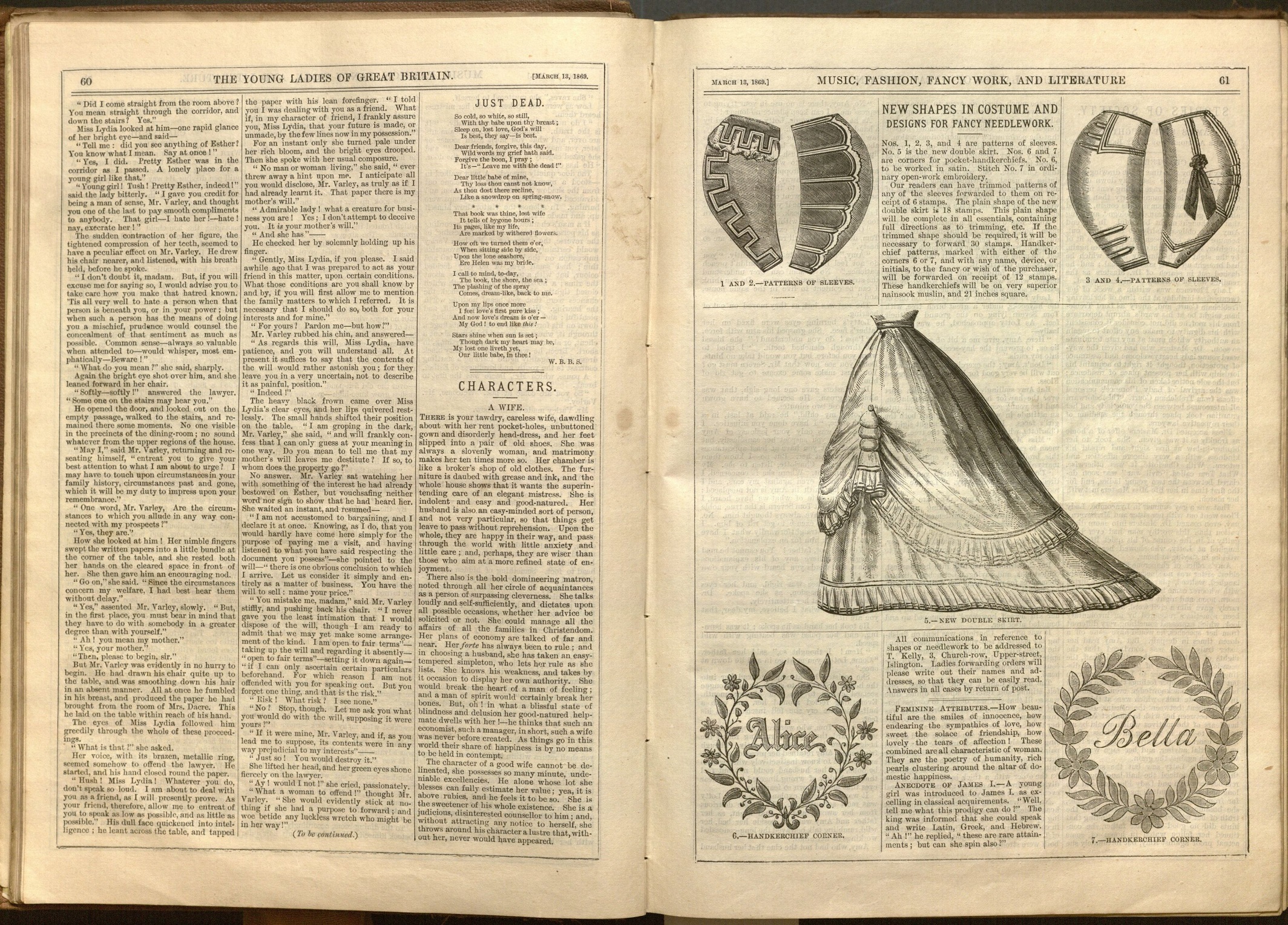

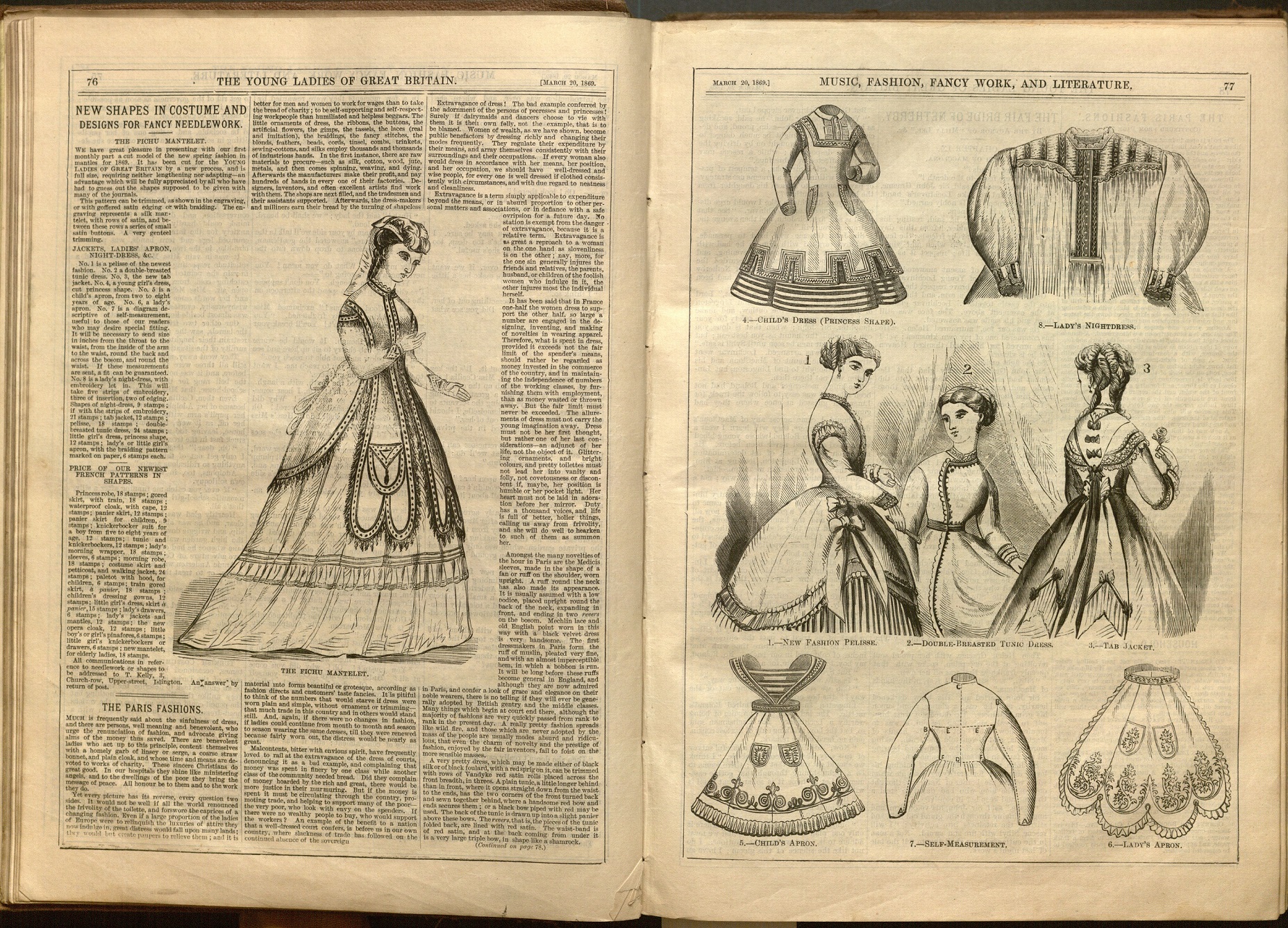

Young Ladies of Great Britain (also known by the longer title, Illustrated Treasury for Young Ladies of Great Britain) ran between 1869 and 1871 before continuing on until 1874 under slightly different titles and formats. Though each issue touched on the newest fashions (in England and in Paris), the first page of the weekly was usually reserved for one of the pieces of fiction serialized in its sixteen pages, accompanied by an attention-grabbing (and often melodramatic) illustration. Priced also at a penny, the magazine targeted a younger readership than The Ladies’ Penny Gazette, and in its mission to divert and educate, lacks the edge at times found in the earlier magazine. A piece simply titled “Characters; A Wife” (see the middle image below) offers a discussion of three “types” of wives: the tawdry, careless wife; the domineering matron; and “the good wife,” whose character “cannot be delineated, she possesses so many minute, undeniable excellencies.” Men aren’t entirely spared from this typology; the husband who is drawn to the “domineering matron” is described as an “easy-tempered simpleton, who lets her rule as she lists.”

Fashion for Victorian Brits: Illustrated Treasury for Young Ladies of Great Britain. 1.4 (1869 March 13) and 1.5 (1869 March 20). Call Number: O’Hegarty D390. Click Images to enlarge.

Whatever their circulation might have been in their day, these magazines are now quite scarce. KU appears to hold the only library copy of The Ladies’ Penny Gazette in North America, (with copies also recorded at the British Library, Oxford, and the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in the Netherlands), and KU, New York Public Library and the British Library are the only places listed in WorldCat as holding physical copies of Young Ladies of Great Britain. These weeklies are “rare birds” indeed, but the fascinating cultural texts they offer make them worth seeking out.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian