Gegrindswile: KU’s Old English Word

June 5th, 2017Old English is the earliest form of English spoken by the Germanic tribes residing in England between 5th-century CE through the middle of the 1100s. It is the language of Beowulf, and most speakers of modern English would find it largely unreadable without some training. The first lines of Beowulf, for example, are “Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum / þeod-cyninga, þrym gefrunon, / hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon!” (Try your hand at translating the lines, then highlight the remainder of this parenthesis to see an English translation: “Yes, we have heard of the greatness of the Spear-Danes’ high kings in days long past, how those nobles practiced bravery.“)*

In 1066 at the Battle of Hastings, William of Normandy earned his epithet “the Conqueror” by defeating the forces of England’s King Harold. The Norman Conquest brought with it an influx of the French language from the new rulers and this combined with other linguistic influences to transform the English language over many decades, ultimately yielding Middle English, the language we associate with Chaucer.

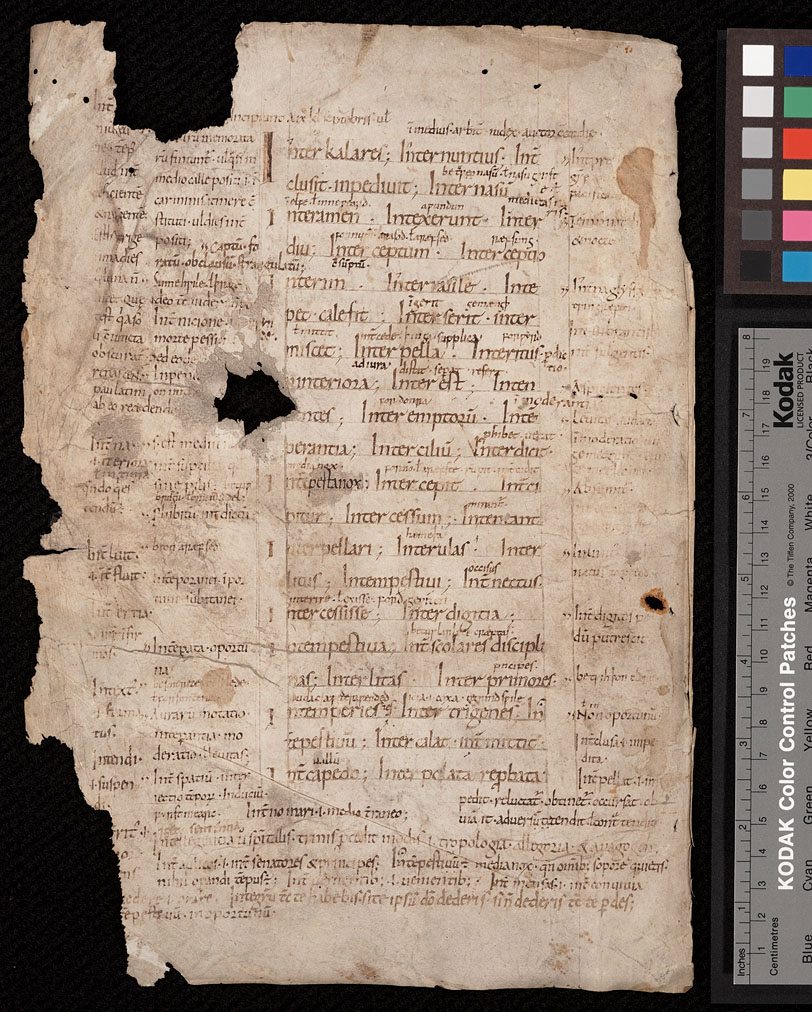

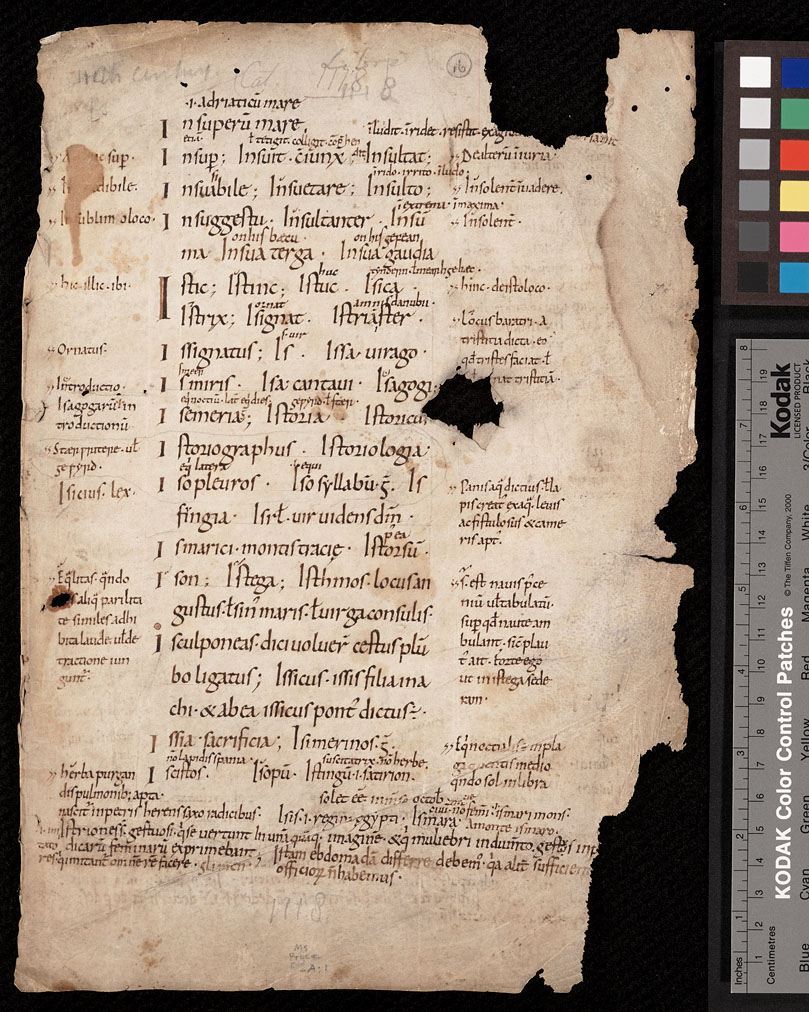

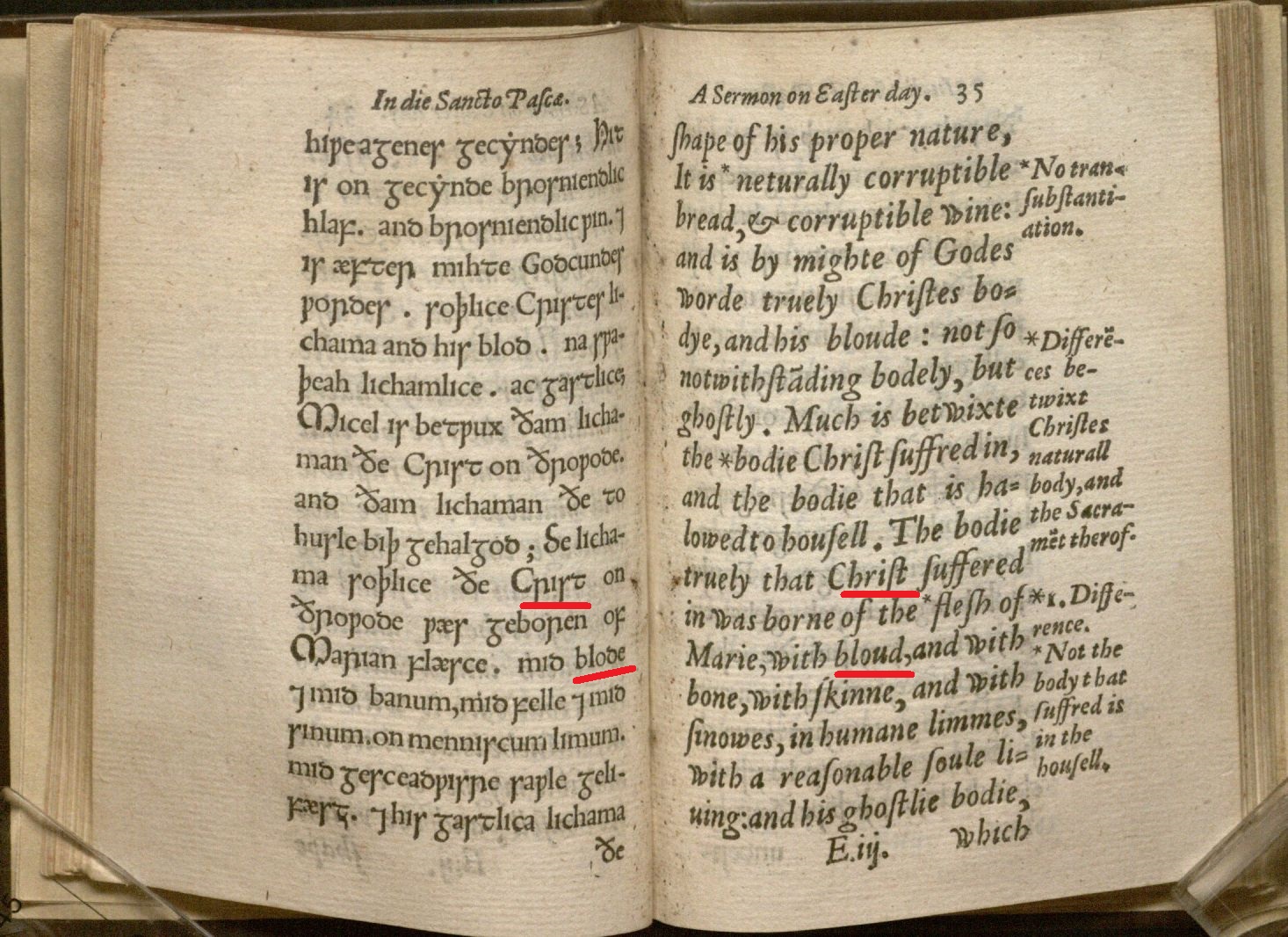

Spencer Research Library holds three Old English leaves, each with its own fascinating story. The leaf shown below (in its recto and verso sides) is an early 11th century glossary giving brief definitions of difficult Latin words. Most of the glosses are also in Latin, but some are in Old English. The two sides of the leaf cover the Latin words interkalares to istingum.

Latin glossary with Latin and Old English glosses, covering the words interkalares to istingum.

Worcester (?), West Midlands, England, circa 990 – 1010. Call #: MS Pryce P2A:1 Click images to enlarge.

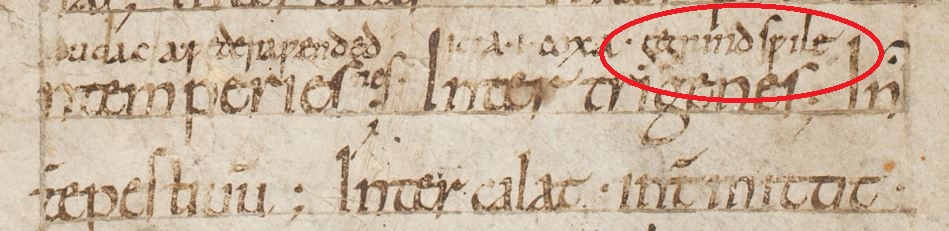

Though rather weathered-looking, the leaf contains perhaps the sole surviving instance of an Old English word: gegrindswile. Like many words of Germanic origin, gegrindswile is a compound. Its two parts —gegrind and swile– survive in other texts, but this leaf is the only instance recorded in the Dictionary of Old English Corpus of the two combined. Together they form a single word meaning “a swelling caused by friction, a chafing or galling (of the skin),” which glosses the Latin word intertrigenes.

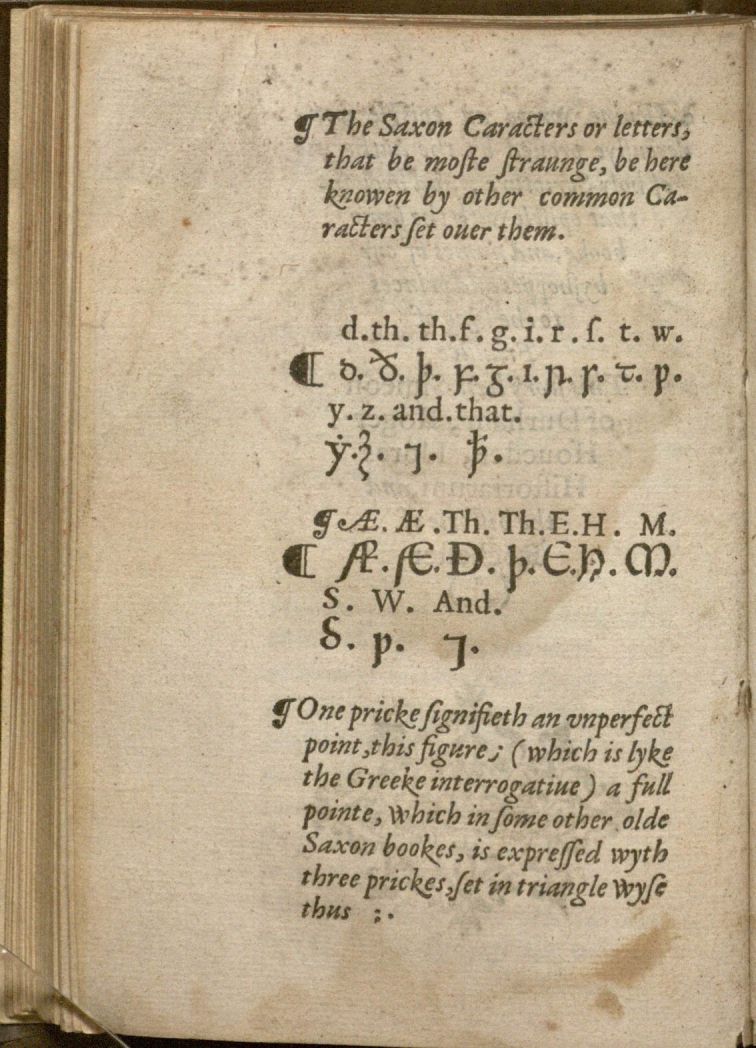

Look closely and you’ll notice that gegrindswile contains a letter that does not survive, as such, in modern English: “ƿ.” This is the runic letter “wynn,” which represents our modern “w” sound. KU holds only a single leaf (two pages) from the glossary; however, the British Library holds a seemingly related manuscript. Its collections include a Latin glossary for the letters A-F, also with Old English glosses, written in the same scribal hand as KU’s leaf.

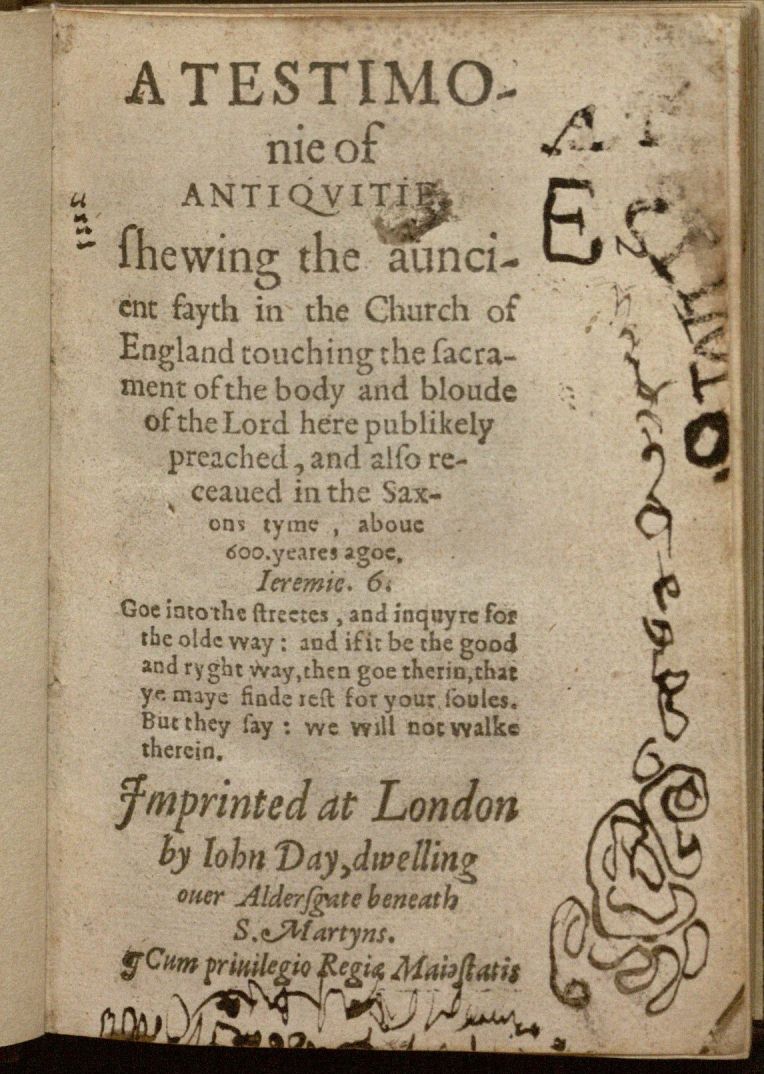

This leaf is currently on display as part of Spencer’s Research Library’s exhibition Histories of the English Language:

From the Old English of Beowulf to the Middle English of Chaucer to the many dialects that make up our modern tongue, the history of English is a history of change. Featuring materials from KU’s Kenneth Spencer Research Library, this exhibition explores English as embodied in the writings of its practitioners, whether celebrated authors, such as John Milton and Toni Morrison, or scholars, lexicographers, and grammarians, such as Elizabeth Elstob, Samuel Johnson, Robert Lowth, and Noah Webster, or anonymous and little-known writers of “everyday” English. In manuscripts and books dating from 1000 CE to the present, visitors will encounter the varied forces at work growing, codifying, standardizing, governing, reforming, describing, and reinventing English.

The exhibition is free and open to the public in Spencer Research Library’s gallery space any time that the library is open. Histories of the English Language will be on display through August.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian

*The English translation of Beowulf is from that by R.D. Fulk in The Beowulf Manuscript: Complete Texts and The Fight at Finnsburg. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 3. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press 2010. Call #: PR1583 .F85 2010 (Watson Library)