Resources About Slavery at Spencer Research Library

March 29th, 2014The success of and critical acclaim for the recent film 12 Years a Slave has generated an increased public discourse about the history, significance, and lasting implications of slavery in the United States. Beyond Spencer’s African American Experience collections, a perhaps surprising number of sources in both the Kansas Collection and Special Collections highlight various components of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century slavery from multiple points of view.

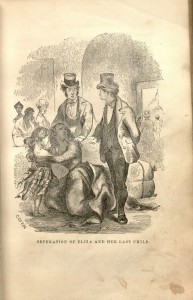

“I have seen mothers kissing for the last time the faces of their dead offspring,”

wrote Solomon Northup in Twelve Years a Slave, “I have seen them looking down

into the grave, as the earth fell with a dull sound upon their coffins,

hiding them from their eyes forever; but never have I seen

such an exhibition of intense, unmeasured, and unbounded grief, as when Eliza was parted

from her child.” Call Number: Howey B1584. Click image to enlarge.

When researching the past, it’s important to keep in mind that the written historical record – including published and unpublished sources – reflects various contexts within the broader society in which they were originally produced. In Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, historian Ira Berlin describes the relationship between masters and slaves as “profoundly asymmetrical,” writing that it was constantly being negotiated but “always informed by the master’s near monopoly of force.” However, Berlin also asserts that

Knowing that a person was a slave does not tell everything about him or her. Put another way, slaveholders severely circumscribed the lives of enslaved people, but they never fully defined them. Slaves were neither extensions of their owners’ will nor the products of the market’s demand. The slaves’ history – like all human history – was made not only by what was done to them but also what they did for themselves (2).

Given this context, it’s not surprising that a population of people denied the ability to read and write over the course of generations did not produce voluminous written documentation. However, as Berlin hints at, the written record is not completely bereft of accounts by free and formerly enslaved African Americans, describing their own experiences in their own voices.

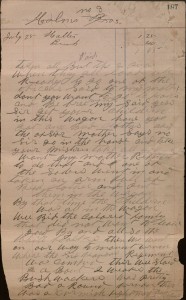

Andrew Williams’ narrative is the sole unpublished, handwritten narrative by a formerly enslaved person in Spencer’s collections. Williams (d. 1913) was a slave near Springfield, Missouri, who served in the Civil War and survived Quantrill’s 1863 raid on Lawrence. Williams’ eleven-page narrative begins around the time he acquired his freedom and describes his experiences in the Civil War.

Andrew Williams, along with his mother and siblings,

was freed in September 1862 by the 6th Kansas Regiment,

described on this page of his narrative. During the raid on his owner’s farm,

the soldiers also killed livestock and confiscated guns and food.

Andrew Williams Collection. Call Number: RH MS P42. Click image to enlarge.

More numerous in Spencer’s holdings are published narratives by former slaves, including Olaudah Equiano, Juan Francisco Manzano, Sojourner Truth, Henry Box Brown, John Thompson, Thomas H. Jones, and Jermain Wesley Loguen. Also among Spencer’s holdings is an early printing of Solomon Northup’s narrative, Twelve Years a Slave.

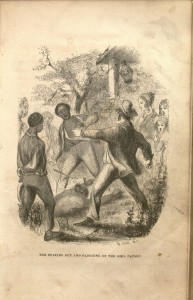

“It was the Sabbath of the Lord…peace and happiness seemed to reign everywhere,

save in the bosoms of Epps and his panting victim and

the silent witnesses around him.” Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave.

Call Number: Howey B1584. Click image to enlarge.

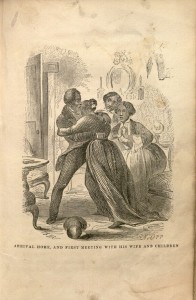

“They embraced me, and with tears flowing down their cheeks,

hung upon my neck,” wrote Solomon Northup at the end of his narrative,

Twelve Years a Slave. “But I draw a veil over a scene

which can better be imagined than described.”

Call Number: Howey B1584. Click image to enlarge.

Supplementing these sources are unpublished documents and published accounts by slaveholders and others who vigorously defended the system and by whites who passionately opposed it. Several of these works are based on the author’s personal observations of the treatment of slaves.

For example, Spencer’s Kansas Collection contains the estate records for Jackson County, Missouri, resident John Bartleson. These documents relate to the Bartleson enslaved African Americans and their legal disposition as property in the settlement of the estate. Additionally, the Kansas Collection also includes bound volumes of records from Natchez, Mississippi, located on bluffs above the Mississippi River about 100 miles upriver from New Orleans. Home to wealthy planters’ city mansions, antebellum Natchez had the most millionaires per capita of any city in the United States. These materials don’t directly address the experiences of enslaved African Americans, whose work created that wealth. However, much can be derived from these meticulous records, which document the management required to operate a sizable plantation and the business transactions of other local enterprises like a medical practice, medical society, and general store.

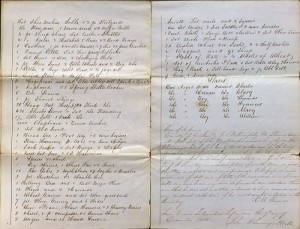

Pages from “a full inventory” of John Bartleson’s property showing

six slaves listed as part of his personal estate, 1848.

John Bartleson Estate Collection. Call Number: RH MS 867. Click image to enlarge.

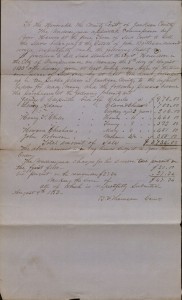

Auctioneer’s report from 1853 listing individual and total prices for

Charles, Clara and child, Courtney, Thomas, Fanny, Mary, and William.

It is assumed that they were members of one family separated by this sale

“at the Court House door in the City of Independence [Missouri].”

John Bartleson Estate Collection. Call Number: RH MS 867. Click image to enlarge.

Finally, numerous printed volumes in Spencer’s holdings show slavery was a much-considered topic that was also hotly debated in government and in public. Especially strong are works examining slavery and the slave trade in Great Britain and the British Empire in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Other works, focusing on the United States, show how the dispute over Kansas and the expansion of slavery into new territories was waged in print and how Kansas became a political and physical battleground for pro- and antislavery forces.

Caitlin Donnelly

Head of Public Services